|

||||

|

|

|||

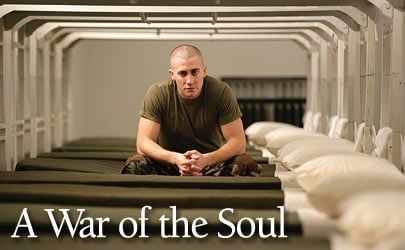

| Jarhead, shot by Roger Deakins, ASC, BSC, puts an existential spin on a Marine’s experiences during the Gulf War. |

|

|||

When Anthony Swofford’s 2003 Gulf War memoir Jarhead first appeared in bookstores, Roger Deakins, ASC, BSC, snapped up a copy. “It was a really different and interesting take on the Kuwaiti war, but I really didn’t see it as a film,” the British cinematographer confesses. It’s no wonder: written by an ex-Marine who took part in Operation Desert Storm, the book is a nonlinear narrative that blends chronicle and essay, alternating between depictions of military life, autobiographical flashbacks, and raging asides on America’s role in the Middle East. Deakins’ thinking changed after he was approached by director Sam Mendes. A veteran of both motion-picture and theatrical stage productions, Mendes had previously contacted Deakins to discuss The Kite Runner, but when that project stalled, Mendes said, “I’m doing this other film you might like.” Deakins was impressed with the screenplay by William Broyles Jr., which straightened out the narrative and brought its military elements to the foreground. “What’s so good about the book and the script is that they don’t present a conventional war story,” the cinematographer offers. “The fact is, nothing happens. It’s really about these kids being taken somewhere they don’t understand, to fight a war they don’t understand — other than the fact that it’s for oil,” says Deakins. “The story is not about the battles; it’s not full of special effects and explosions. It’s one soldier’s very personal story and it presents a very real view of war.” Deakins concedes that he felt a bit intimidated at the prospect of working with Mendes because he knew he would be filling some very big shoes: those of the late Conrad Hall, ASC, who had collaborated with the director on the films American Beauty and Road to Perdition — both of which earned the revered cinematographer Academy Awards for Best Cinematography. “It made me very nervous, really,” Deakins admits. “Connie’s work inspired me so much when I was starting out, and I was lucky enough to get to know him as a friend when I eventually came to live in Los Angeles. Connie had enthused about working with Sam on numerous occasions, and now I know why. Sam is so smart and imaginative. He knows what he wants, but he’s also open to ideas. I found working with him to be a very satisfying and stimulating experience.” Jarhead begins with Swofford (Jake Gyllenhaal), nicknamed “Swoff,” progressing through boot camp and pondering his past via brief flashbacks to his childhood in a military family, his blonde sweetheart, and his reasons for enlisting. The story then moves to Saudi Arabia, where Swoff’s division trains and waits in the empty desert for nearly seven months. Swoff tries out for the Marine Corps’ sniper platoon and is soon armed with state-of-the-art long-range rifles — but still no target. It’s not until the film’s third act that the troops finally see their first Iraqis, in the form of charred cadavers strewn along the Highway of Death after a series of U.S. airstrikes. The platoon continues towards the burning oil wells of Kuwait, where Swoff and co-sniper Troy (Peter Sarsgaard) are sent on a reconnaissance mission near an airfield. After their assignment is aborted, however, there is no transport to pick them up. The snipers fear they are forgotten, or worse, that their battalion has been wiped out. They make their way over the dunes to the assumed battalion coordinates, where their story takes an unexpected turn. In conceptualizing Jarhead’s look, Mendes was keen on using handheld camerawork almost exclusively. “He wanted something very free and organic,” says Deakins, “but I think he was nervous about me doing it.” After all, the cinematographer explains, his recent films were in many ways more traditional. For example, Intolerable Cruelty (see AC Oct. ’03), one of Deakins’ eight collaborations with the Coen brothers, is a stylized, storyboarded, crane-and-dolly production that seems a far cry from the approach Mendes sought for Jarhead. But Deakins offered some persuasive reassurances. “I told Sam early on, ‘I come out of documentaries, and I love shooting handheld. It’s my documentary experience that has led me to be so concerned about framing and camera movement, and it’s also the reason why I operate on all of my movies.’” Indeed, as a young National Film School graduate, Deakins spent seven years shooting and directing documentaries, and even filmed in the war zones of Rhodesia and Eritrea. Still, his last narrative feature to involve much handheld work was the 1986 drama Sid and Nancy. “I’ve always wanted to do a film totally handheld, so when Sam said that, I jumped at the chance.” Jarhead ended up with a handheld look that’s subtle but effective. “It’s not like it’s rough and raw newsreel,” Deakins notes. “When I was timing the film this weekend, I thought, ‘Wow, you really wouldn’t know this is handheld.’ Every now and again, you’re running with people or whatever. But it’s mostly just a way of giving the actors freedom and lending a sense of spontaneity to the coverage. “First and foremost, Jarhead is a character-driven film,” he adds. “Sam and I felt that thinking on our feet would give the film an immediacy it might otherwise lack. In fact, during the shooting, we would often censor each others’ ideas for a shot or coverage of a scene, especially if one of us felt that what might seem to be a ‘cool’ shot would only serve to draw the audience out of the story and not into it — simply by putting them in a position that was an unrealistic point of view for an observer. I really dislike the flamboyant style of camerawork you see in many war films, where the camera soars above the battlefield or tracks behind a falling bomb. That’s just war seen as a video game, and Jarhead is certainly not that. “I really don’t believe that there is a ‘look’ for a war movie or a ‘look’ for any other genre of movie,” Deakins maintains. “The ‘look’ comes from the script and the characters, and a good script conjures up its own look. We did want to depict the harsh environment of the desert and the brutality of war, but for us it was also about the boredom and monotony of the wait, and a sense of claustrophobia in an endless desert.” |

|

|||

|

next >> |

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|