|

||||

|

|

|||

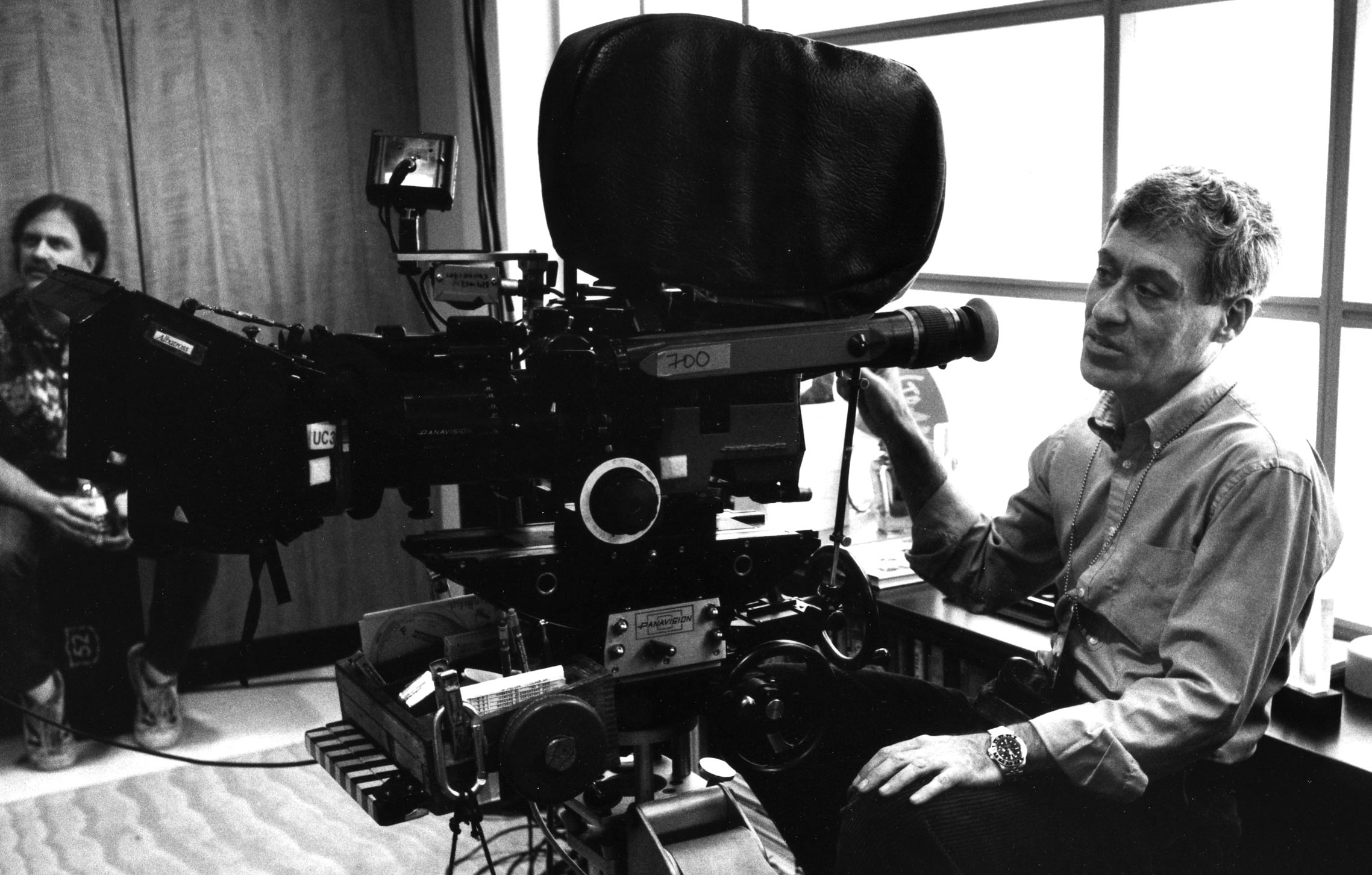

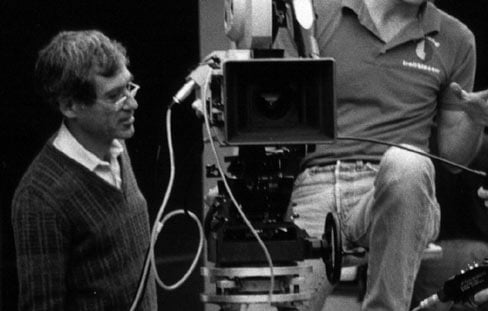

| Woody Omens, ASC is honored by the Society with its Presidents Award. |

|

|||

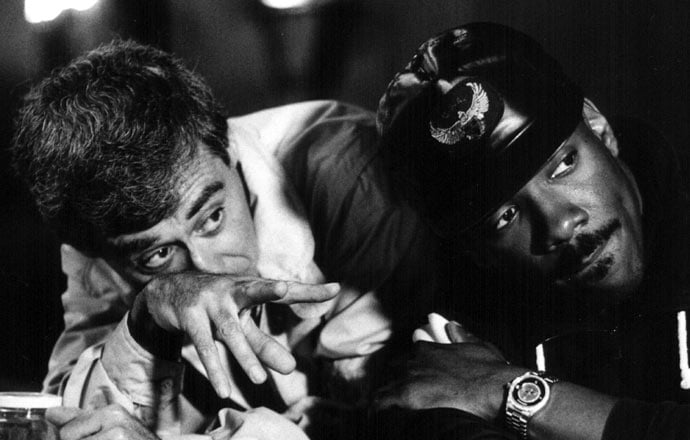

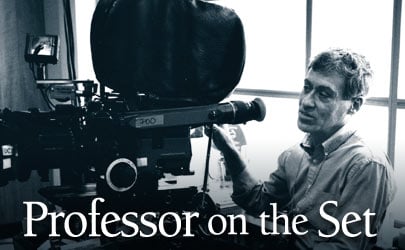

“Loyalty. Progress. Artistry.” Those three words have served as the ASC’s motto for 85 years, inspiring its members to look beyond their role behind the camera to serve and educate not only their comrades, but the filmmaking community at large. This selfless spirit is exemplified by Sherwood “Woody” Omens, ASC, who will be honored with the Society’s Presidents Award next month. Not incidentally, Omens and longtime friend Michael Margulies, ASC co-founded the ASC Outstanding Achievement Awards in 1985. When asked how receiving the Presidents Award has helped him reconsider his work, Omens replies with the humility that those close to him know so well: “I think I’ve done okay for someone whose career got started so late in life.” Born in Chicago, Omens became interested in drawing and painting at an early age, and he studied both subjects at the Art Institute of Chicago. Upon graduating, in 1959, Omens taught art at a junior high school in Oak Park, Illinois, and painted during his spare time. After an exhibitor suggested that he take photos of his work, Omens began experimenting with a Pentax camera. “Pretty soon, I was teaching a junior-high photography class as well,” he says. “I shot all kinds of experimental images of Chicago, and spent 4 to 11 p.m. in the school darkroom, processing and printing black-and-white stills.” Though encouraged to pursue his stills work by abstract expressionist photographer Aaron Siskind, Omens had already begun “wondering what it would be like to take movies, so I dug my father’s 16mm Keystone camera out of storage.” Intending to make educational films, he moved to Los Angeles with his wife and child and enrolled in the University of Southern California’s School of Cinema-Television. He graduated three years later, in 1965, with a master’s degree and an emphasis on cinematography. “I’d become fascinated by the idea that there were two people on the set who had responsibilities for making decisions,” he notes, “and I wrote my thesis about the roles played by cinematographers and directors and how they related. Was it a collaborative process or a dictatorship?” Seeking answers, Omens interviewed a number of ASC greats for his paper, including Charles Clarke, Daniel L. Fapp, Arthur Miller and Harry Stradling. However, it was a chance encounter with another Society member, James Wong Howe, that left perhaps the most indelible impression on the budding filmmaker. “I recognized him walking on the street one evening and spoke to him,” recalls Omens. “He asked who I was, and I told him I was a student at USC Cinema. He gave me an extemporaneous, 20-minute lesson. He said, ‘Imagine you are photographing a man sitting on a park bench and want to express his feelings of loneliness. What would you do?’ I didn’t have an answer, so he explored all the factors, choice of lenses, camera position, time of day and what the light was like. Then he asked, ‘How would the man sit on the bench? Where is he sitting and which way is he facing?’ I didn’t fully realize until years later how profound those questions were. It was an important part of my education.” After graduation, Omens took jobs as a film loader and assistant cameraman on 16mm documentaries. He eventually stepped up to shooting, but the difficulty of getting into the camera guild at the time prevented him from moving into narrative work. “That was a valuable experience,” he says of his documentary days. “It taught me how to work quickly and make the most of natural light. But I wanted to shoot features and knew I needed experience with 35mm cameras, so I showed my documentaries to John Urie, who had a successful commercial-production company. About six months later, he called and said he had a job. “John put me to work in two ways: I assisted his cinematographers, Ed Martin and John Hora [ASC], and I shot test commercials. After about a year, I got bold enough to say to John, ‘How about letting me shoot all the time?’ He said no. After thinking about that for a while, I made a sample reel and got hired by other directors to shoot commercials for different production companies. It was a very experimental time for commercials. I was learning my craft and getting to use the best equipment.” While shooting documentaries, Omens shared an Academy Award nomination for the documentary short subject Somebody Waiting (1972), on which he served as a producer and the cinematographer. Six years later, he caught the break he’d been waiting for: “Jim Sommers, a commercial producer I was working with, introduced me to Robert Ellis Miller, who was going to direct the television movie Ishi: The Last of his Tribe, which had a terrific script. What I brought to it was my commercials training, my ability to turn out shot after shot, scene after scene, very quickly. What commercials also taught me was how to light close-ups. Great masters and great close-ups make great cinema; the rest is connective tissue. I shot a couple of other TV movies after that — Stone and Man in the Santa Claus Suit — and then I shot the Magnum P.I. pilot [in 1980].” Photographed in Hawaii, Magnum P.I. earned Omens his first Emmy nomination. He later won consecutive Emmys for the telefilms An Early Frost (1986), Heart Of The City (1987) and I Saw What You Did (1988). He was also nominated for Evergreen (1985) and Alfred Hitchcock Presents (1986). Omens earned an ASC Award in 1987, for the pilot for Heart of the City. “I love working with good directors, people who are truly trying to communicate something to the audience” he says, citing Evergreen director Fielder Cook and An Early Frost director John Erman as two favorites. “A good director helps you do your best work. But the challenge of being a cinematographer is that you don’t always know who your next partner is going to be. Will he be open-minded, confident enough to accept multiple and often conflicting opinions? You have to have an ego to be a director, but not so much ego that it precludes you from accepting input. The best directors will take ideas from craft services! It’s the cinematographer’s job to help that process, to be of service to the script, the director, the actors and, of course, themselves. There’s a hierarchy, and you’re often putting other people first. That’s part of the job. |

|

|||

|

<< previous || next >> |

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|