The visual effects team for Mission to Mars raced against the clock

— and a competing project.

|

| Time was of the essence during the frantic postproduction phase of Mission to Mars, which Disney was determined to have in theaters well ahead of Warner Bros.' rival Mars flick, Red Planet.The competition forced Disney's in-house effects firm, DreamQuest Images, to split the work with Industrial Light & Magic (as they'd done previously on Mighty Joe Young), and to bring in Tippett Studios and a host of other houses as well. |

|

"Because of the other Mars film, the production had an extremely aggressive, accelerated post schedule, and the number of shots also grew," says DQ founder and visual effects supervisor Hoyt Yeatman, who spoke to AC in the midst of the process. "We quickly realized that there was no way we could handle the types of sequences we were planning to do. Originally, the whole show was probably just shy of 200 shots, and now ILM alone has over 200 shots! We have about 140, Tippett's got 50, and there are a ton of wire removals, screen burn-ins and sky replacements, most of which are being handled by Henson, Cinesite and CIS. We did 400 animatics, not just of the effects shots themselves, but of the entire sequences. Basically, once the astronauts leave Earth in the first five minutes, it's a hardware film: everything you see is either manufactured or enhanced in some way, shape, or form."

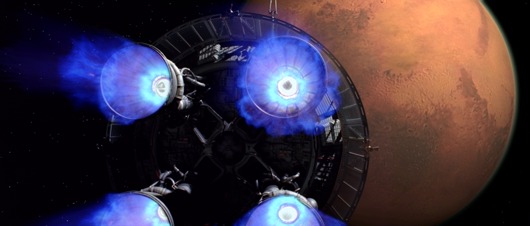

DreamQuest's large workload involved some extremely CG-heavy sequences, so Yeatman chose to handle the Mars II recovery vehicle, visualized by production designer Ed Verreaux, as a highly detailed miniature. "We made the model as large as possible for the types of shots that we had, and yet just large enough so that we could get the wider shots that we wanted it turned out to be about 21 1/2' long!" Yeatman enthuses. "Then, Mike Sorenson from Source and Design built the biggest model-mover I've ever seen. We also built a digital replica of the stage, including a digital replica of the model-mover and the camera system; all our motion-control programming was done virtually, so we would plug the moves in on the stage, and the motion-control rig would shoot that move without any manipulation. That came in very handy when we were trying to dovetail with certain complex moves. For example, in one sequence, [director] Brian De Palma wanted to start in deep space, reveal the spaceship, fly up to and around the spaceship, then fly into a window and show the two main characters.

"We also built a virtual version of the Mars II that we used with the space station, which was an entirely digital model. That was the best way to go, since our craft was based on the International Spacestation, which has all of these delicate little details that would have been very hard to build in miniature. For the most part, though, we tried to do as much with models as possible, because I realized that we'd be spending a lot of digital energy creating the vortex sequence, which involved a lot of particle animation."

The vortex is unleashed when the first Mars explorers come across what seems to be a pinnacle of ice atop the red planet's famed "Face." When the astronauts drive their rover to the base of the mountain, they inadvertently set off a perimeter alarm that unleashes the vortex. "The vortex is a supernatural energy field that removes the Martian soil and the rubble around this mountain, and it takes the form of this huge twister that attacks the astronauts," Yeatman relates. "As the 'Face' is uncovered, the dust and debris is spun up into a giant twister that's several hundred feet high, which then keels over horizontally and becomes almost like a serpent on the ground. It's about 50' in diameter, and the audience will be looking right inside its mouth."

DreamQuest's animation team created the vortex using the Hookah renderer that they initially designed for the particle "gas jets" shooting out of the meteor in Armageddon. "The technique of creating the gas itself was procedural," he elaborates, "but our animators have been working on Hookah to allow us to control those procedural elements via animation to create a character. It takes two different types of animators: a traditional animator animates the character, and then the Hookah procedural animators called TDs actually translate that into the final 'look' of the vortex. In other words, a traditional animator moves a series of concentric tubes to create the motion of the vortex, without knowing exactly what's happening inside the vortex. Then that position geometry goes to the Hookah animators, who add these multiple concentric tubes, which work within the Hookah software to control the forces inward, the forces outward, and the turbulence, to get the look or the behavior of the outside Hookah force. There is no solid form; using Hookah, we created this amazing, surf-like vortex that consists completely of a hundred million particles or more. It takes forever to render, and it's a mess to light, but the aesthetic is interesting and spectacular. I've never seen anything like it, which is pretty cool."

DreamQuest called in an unusual backup to help with the vortex sequence: Tippett Studios, an outfit mostly known for its groundbreaking character work on films such as Jurassic Park and Starship Troopers. On Mars, Tippett's wizards found themselves animating rolling rocks. "There really isn't a great deal of character animation, just a lot of rocks flying around," concedes Tippett Studios visual effects supervisor Brennan Doyle. "There's a sequence of shots in which one of the astronauts gets sucked into a fissure in the ground, so we've been ripping up the ground around the character and surrounding him with debris rolling along the ground. We created all of that using a lot of particle-type renders of rocks and dust. Of course, our rocks do have lots of character: some are happy, and some are not so happy!"

Ironically, it fell to ILM to create the film's climactic sequence, during which viewers do get a glimpse of a real-life Martian - in a way. When the astronauts venture into the exposed "Face" on Mars, they discover it to be a vast, featureless white environment leading to a huge rectangular black opening. As they pass into the blackness, they see a holographic planetarium display a stylized three-dimensional textbook illustration of our solar system, replete with orbit rings. Hovering over the display is the stylized hologram of a female Martian, who proceeds to tell the story of her planet's destruction. "The astronauts notice that Mars does not look like the Mars of today; it looks a lot like the Earth, and in fact, it's the fourth planet out from the Sun," reveals ILM's visual effects supervisor John Knoll, who recently completed hundreds of shots for Star Wars Episode I The Phantom Menace. "Mars gets struck by a comet, which creates a giant impact crater. The astronauts watch as the planet slowly dies and Earth takes its place. As they're observing all of this, they suddenly notice that they're not alone and that this Martian figure is with them."

The climactic sequence lasts a whopping 10 minutes and involved a CG-created environment, digital planets, and of course, a 3-D animated Martian none of which was actually on the set during physical production. "We shot the actors on a set, but the set didn't really consist of much other than a velvet black backing and a black, shiny floor," Knoll says. "We then added a starfield behind them, plus the Sun and the planets. We created the destruction of Mars using particles, tricky Renderman shaders and various animated Maya elements. Maya's a really TD-friendly tool; it's very flexible thanks to the embedded programming language, and it's really fantastic to use."

The bulk of the scene's interior was also created via ILM's computer wizardry. "There aren't any walls to depict until the very end of the sequence, when there's a big pullback revealing that the entire inside of the 'Face' is a giant alabaster shell," Knoll details. "It's almost like being inside a gigantic aircraft hanger. It's actually a minimalist temple with columns running along the walls, each of which is shaped like one of the Martian figures. There are also some other sculptural elements, including a cupola with four Martians, hands outstretched, forming these columns around the solar system display in the center. We created all of that digitally."

The Martian herself appears in the middle of the solar system, silhouetted by the sun. "It's just supposed to be a projection," Knoll explains. "She's not supposed to be a living, breathing creature, but more of a stylized, idealized representation of a Martian. She's a benevolent, friendly presence, almost like a Francuzzi sculpture very tall and thin with elegant, elongated proportions and a bit of an Art Deco look. They definitely couldn't do the Martian using a person in a suit, because she's not proportioned like humans and she has no legs. She's like Casper the Ghost, just sort of floating along. She doesn't speak; she communicates with gestures."

Despite the large numbers of effects houses brought on board Mission to Mars, and the hundreds of computer-generated, miniature and practical effects shots they created, the greatest challenge DreamQuest's Yeatman faced was ensuring that all of the film's imagery meshes into a coherent whole. Sadly, Mission to Mars is the last film that will bear the DreamQuest moniker. Acceding to the wishes of its parent company, Disney, DQ will henceforward be known as The Secret Lab (TSL). The name change marks the end of an era, but here's hoping that DQ's maverick spirit will live on the firm's new incarnation.