|

||||

|

|

|||

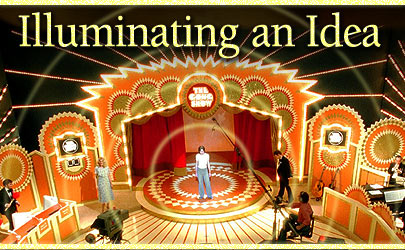

| A key transitional sequence in Confessions of a Dangerous Mind is captured in the camera by Newton Thomas Sigel, ASC. |

|

|||

Newton Thomas Sigel, ASC knew from the start that collaborating on Confessions of a Dangerous Mind with first-time director George Clooney would give him an opportunity to be very inventive with the visuals. First, the script (by Charlie Kaufman, based on the book by game-show pioneer Chuck Barris) was a unique piece of material that spanned more than four decades and floated in and out of segments that might or might not be fantasies. Second, Sigel, who had worked with Clooney on David O. Russell’s Three Kings, had come to know the actor, and he knew Clooney wanted his directorial debut to be something special. "When actors start out directing, they’re often concerned first and foremost with the performances," Sigel observes. "Obviously, George did a great job with that, but he’s a also real lover of film – of film history and the craft. He wanted to do something that was special in every [aspect] of filmmaking. Confessions was a project that lent itself to a very cinematic approach." Sigel took advantage of the high-tech capabilities available through digital-intermediate technology by color-grading the entire film at Technique in Burbank. During production in Montreal, he had the lab, Covitec, create digital dailies during production so that Clooney, the film’s producers and department heads could see the final look of the product taking shape. Despite this high-end approach to the visuals, however, Clooney was also interested in taking a more handmade approach to some aspects of the production. This is particularly true of the film’s many unusual transitions, during which characters move from one point in the story to the next. Rather than using composites and visual effects, Clooney wanted to do much of this work in camera. In one montage, which shows Barris overseeing the creation of a pilot for his hit game show The Dating Game, the camera pans back and forth constantly to reveal new contestants sitting in the same seats while asking and answering questions. Clooney choreographed the action and camera movement to create the effect in a single shot. "We had the actors running all over the place," Sigel recalls. "Someone would get up and another one would sit down. There’s a kind of solidity to the camera and the movement when you approach things this way that helps the audience trust that they’re watching human trickery, not electronic trickery." A particularly important transition occurs early on, when a young Barris (Sam Rockwell), frustrated that he must listen to the inane chatter of his girlfriend Penny (Drew Barrymore), suddenly gets the career-making idea to package vapid dating discourse into the form of a TV game show. The idea would become The Dating Game, his first hit. At this point in his career, Barris is a low-level TV executive sharing a tiny New York apartment with Penny. One morning, inside his small kitchen/bathroom (the tub is in the kitchen in the old tenement style), Barris adjusts his tie while Penny relaxes in the bathtub behind him. As she prattles on about a dream she’s had, the scene cuts to a shot of Barris from the POV of the mirror. As the concept for The Dating Game begins to coalesce in his mind, the camera dramatically pushes into an extreme close-up so that his eyes fill the screen. Then, in the same shot, the camera pulls out as Barris comments on his annoyance at having to deal with Penny’s banter. Initially, it seems as if he’s still addressing Penny, but as the camera continues to pull out, it becomes clear that we’ve now assumed the POV of a network executive (Jerry Weintraub) listening to Barris pitch his idea in a boardroom. By the time the shot resolves, we’re looking over the shoulder of the seated executive as Barris presents his concept for The Dating Game, nervously holding a foamcore mock-up of the set as a visual aid. "It’s all one shot," Sigel explains. "We had two conjoined sets: the kitchen and the boardroom. Sam Rockwell and the camera were on a big turntable so that when we pushed into his eyes, the grips could start spinning the turntable – a motor would’ve been too noisy – until Rockwell was positioned in front of the boardroom set. When the camera pulls out, it looks as if some time has passed and he’s now in a different location." |

|

|||

|

<< previous | next >> |

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|