|

||||||

|

|

|||||

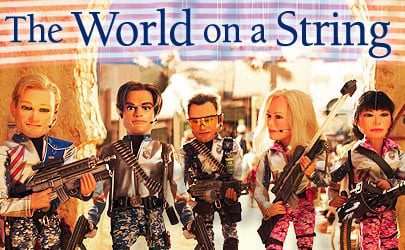

Pope confesses that the constraints the puppets imposed on the photography did challenge his initial ideas about shooting the action picture. “As much as possible, I did try to follow the conventions of the genre and learn from the action geniuses,” he submits. “They often use a lot of hard light and anamorphic lenses, but anamorphic lenses were quickly ruled out on this show because there are virtually no anamorphic macros that would allow us to work so close to the puppets. Instead, to achieve that widescreen aspect ratio, I wound up working in Super 35. Action films also tend to have dramatic lighting — backlight, bold swatches of light, smoke — but we couldn’t adopt many of those conventions because strong backlight would reveal the marionettes’ strings too much. Also, the shape of the puppets’ heads are a bit odd; they have large brow-lines and eyebrows, as well as large eyelids. The Thunderbirds puppets were very similar. When you really look at them, their features are sort of grotesque. They’re not really built to scale, either; their heads are about one-third too large for their bodies and look sort of weird, so it was hard to light them from above and get any light in their eyes. We ended up having to put a light beneath the mattebox, so many times I had lights Velcroed under there. In that way, the look of the film sort of organically dictated itself. The content is action, and the camera movement is like what you’d see in an action film, but the lighting doesn’t follow the formal conventions of an action movie.” To light the marionettes, the cinematographer tended to use Kino Flos. “Now, to my knowledge, that’s not an action convention, but I just couldn’t get a hard light in on the puppets. I had to work more up close and softer than most action movies would. We made up several versions of Mini Flos — two-, three- and four-bulb units that we used to create custom softboxes. We also had Micro Flos around all of the time. They were good eyelights, and they could also be used as kick lights to pick out details on the puppets’ outfits. The mattebox was usually three feet from a puppet, so the lights could be three feet away. Our main key light was often a two-foot four-bank, and one of those placed three feet away could generate quite a lot of ‘heat’ — upwards of a T4 or a T5.6. We’d either use a two-foot bank or a four-bank placed a little farther back so that we didn’t have light dropping off in the shot. Then we’d work with the Mini Flos to wrap the lights around the puppets, creating fill light or putting a little light in their eyes.” Pope photographed Team America on Kodak Vision2 500T 5218 stock, using Panavised Arri 435 cameras fitted with Primo Close-Focus Primes. He also shot the majority of the film without the benefit of printed film dailies. “We were basically dailies-free,” he admits. “We had about 10 days of film dailies, but that’s all we could afford. At the beginning of the schedule, we talked about what we really needed to see, but that was front-heavy in the schedule. We wanted to see a lot in the beginning, but once we got going we were on our own.” Team America features many “large” setpiece sequences that unfold in scenic locations such as Paris and Egypt. Other settings include Mount Rushmore, which conceals Team America’s secret headquarters, and Kim Jong Il’s grand palace and outdoor amphitheater. “We had a big fight set in Cairo, so the production crew built the city itself and the surrounding desert, complete with pyramids,” notes Pope. “For scenes of the characters driving or flying, we constructed huge moving sky backdrops to create the illusion that our vehicles and ships were actually in motion. We put the cars on huge, belt-sander-like treadmills that were painted to look like the desert sand, and we had our various sky backgrounds whizzing by in the background as fast as possible. It was pure silent-movie, Keystone Kops technology, but it was completely ‘sellable’ within the puppet world that we were creating. We were constantly playing with different levels of realism and fakery, and it’s so complicated that I can’t even begin to articulate it. My only point of reference on what worked and what didn’t was when Matt and Trey laughed. If they laughed, I knew we’d gotten it right.” For night exterior scenes in Kim Jong Il’s amphitheater, “we put up space lights and gelled them blue to simulate a night ambience. We then used follow-spots on the stage, as well as a big disco ball and some monumental background behind the puppets — at that scale, of course, ‘monumental’ means 8-by-12 feet. Toplight was also an issue, because the puppeteers’ Condors were always in the way; we couldn’t really light from the top, other than a really soft ambience coming from underneath the Condors. Many times we had to simulate toplight by raking light down the walls, as if it was coming from the top, but then actually light the puppets from the side We didn’t want to light up the strings and we didn’t want to harshly light the puppets with their sort of Neanderthal foreheads.” To help combat the light-sucking factor of the various Condors and puppeteer bridges built over each setup, Pope had custom Kino Flo “softboxes” affixed to the bottoms of the Condors to replace the lost ambience that was being absorbed by the equipment and technicians. “We built the softboxes right to the base of the Condors’ buckets using Kino Flos, 216 diffusion and whatever color was applicable for a scene. We’d then just turn on as many bulbs as we needed to achieve the appropriate ambience.” One of the more controversial sequences in the film will surely be a highly graphic lovemaking interlude between two of the Team America characters. “That scene was hilarious, and it was the most fun for the crew in terms of sheer outlandishness,” Pope enthuses. “Of course, there’s nothing truly graphic about the scene, because the puppets are like Barbies: they don’t have any genitalia. They’re just simulating sex, and it’s totally ridiculous. We had little candles over the bed, Mount Rushmore out in the distance beyond the window and slow dolly moves with foreground elements and the sappiest music ever — all of the schmaltz. It’s a quintessential Bruckheimer moment, in that the emotion the film is trying to create is not supported by the content in any way. In a Bruckheimer movie, people will turn to each other in the middle of battle and reveal their life stories, inappropriately and unbelievably. That also happens in this film. “We were screening some of our rare printed dailies the other night while the projectionist was up in the projection booth, and we were running some fairly bland footage,” Pope recalls. “Suddenly, one shot from the love scene came up and we heard this huge howl from behind the projection-booth glass. Then the projectionist’s voice came through the intercom, and he was saying, ‘I can’t wait to see this movie!’” Stone and Parker, for their parts, feel that Team America has allowed them to cross into a whole new realm of possibilities for future projects. Concludes Stone, “On this project, cinematography and framing were the most foreign elements to us because we come from a background of low-budget films and animation. But we’re learning how important they are, especially when you’re doing a movie where you want to parody or evoke a certain type of film. Bill did a fantastic job and the film looks amazing. Team America may be a big, stupid puppet movie, but it’s great!”

|

|

|||||

|

<< previous || next >> |

||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

||