|

||||

|

|

|||

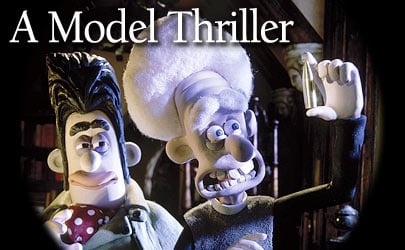

| Directors of photography Tristan Oliver and Dave Alex Riddett crack the stop-motion mystery Wallace & Gromit: The Curse of the Were-Rabbit. |

|

|||

When filmmakers at Aardman Animations began prepping their second feature, Wallace & Gromit: The Curse of the Were-Rabbit, they had reason to believe it would be somewhat less complicated than their first feature, Chicken Run (see AC Aug. ’00). This was in part because the cozy world that had been established in Nick Park’s celebrated Wallace & Gromit short films A Grand Day Out, The Wrong Trousers and A Close Shave promised a handful of key characters and a return to a “thumby,” more obviously handcrafted look, but it was chiefly because the logistical challenges of creating a stop-motion-animated feature were no longer unknown. “It was quite daunting just getting used to working on that scale, and Chicken Run demystified the process,” says Dave Alex Riddett, the supervising director of photography on Chicken Run and co-director of photography on The Curse of the Were-Rabbit. “Knowing what we’d achieve at the end of it meant we could be a bit more adventurous on this one.” In that spirit, and in the hands of co-directors Park and Steve Box (a key animator on The Wrong Trousers and A Close Shave), The Curse of the Were-Rabbit, like its titular shape-shifting monster, sprouted from humble origins into a creature of considerable and surprising dimension: a stop-motion thriller complete with atmospheric fog, mobile monster-POV shots and other stylistic tropes of classic horror movies, all informed by the blend of sophistication and slapstick for which Park’s comedies have become known. “This,” says co-director of photography Tristan Oliver, “is as horrific as Wallace & Gromit gets.” Oliver and Riddett, who have been friends and colleagues since they met in the postgraduate film program at Bristol University in 1982, were well-suited to lead the camera department on Were-Rabbit. They had collaborated on The Wrong Trousers (1993) and A Close Shave (1995), which both won Academy Awards for Best Animated Short Subject, and their extensive experience with stop-motion animation included shared director of photography credit (with Frank Passingham) on Chicken Run, as well as numerous individual credits on short films, music videos and commercials (AC July ’02). Riddett began working for Aardman on a freelance basis in 1983 and became the studio’s only staff cinematographer in 1995, and Oliver has been a regular freelancer there since 1989. Over the course of Were-Rabbit’s 21-month shoot, the pair supervised five other cinematographers: Andy MacCormack, Paul Smith and Fred Reed, who worked throughout the project; Charles Copping, who was aboard during the early stages of filming; and Jeremy Hogg, who moved up from senior camera assistant to cinematographer during the shoot. At the peak of production, all 35 of Aardman’s Mitchell BNCs were in use at the studio’s feature-production facility in Bristol, England. In the film, the intrepid inventor Wallace and his enterprising dog, Gromit, have hatched a humane pest-control business and are busy capturing rabbits in local gardens as everyone prepares for the Giant Vegetable Competition organized by Lady Tottington. When a mysterious nocturnal creature begins plundering the town’s vegetable plots, Wallace and Gromit begin working overtime to catch the culprit — but first, they must determine what it is. When AC visited the set last March, Riddett and Oliver were shooting scenes at opposite ends of the spectrum, illustrating the diverse demands of filming 3-D model animation. Riddett was creating moonlight, firelight and lightning effects for a moody night interior in the vicarage, a set which, at 5' long, was considerably shorter than he; and Oliver was photographing the were-rabbit’s climactic appearance on the lawn in front of Tottington Hall, a 50'x40' set that included fairground rides dotted with more than 4,000 tiny practicals. Standing by were the “actors,” the animators who would eventually be left alone on set. All of the camera moves, focus pulls and lighting changes that the cinematographers designed and tested would be programmed into Aardman’s Strand lighting desks, the technical nerve center of the production, and triggered by the animator with a single button as he or she animated the shot frame by frame. “It’s a bit like a pyramid,” Oliver says of the process. “You start with an empty space, then the set comes in, the set dressers come in, the lighting comes in, the motion-control [rig] comes in, everyone beavers away and beavers away, and then gradually everyone leaves and you’ve just got the animator.” Although the physical scale of Were-Rabbit ultimately matched that of Chicken Run, in one significant respect the cinematographers’ path on the new picture was far smoother: the digital intermediate (DI). In early 2000, when Riddett, Oliver and Passingham began shepherding Chicken Run through the post process at London’s Computer Film Company, no one had carried out a feature-length DI. The filmmakers’ initial plan was to digitally grade only the visual-effects shots, which are pervasive in stop-motion animation because of extensive rigging and compositing, but they soon determined that a full-length DI would be the most efficient way to finish the picture, as well as the safest. “Typically in an animated film there might be a cut in the negative every foot or so,” says Oliver. “This creates a very fragile master, and it would be very risky to run it through the [optical] printer.” Furthermore, notes Tom Barnes, Aardman’s technical director, “We had such a compressed post schedule on Chicken Run that it wouldn’t have been physically possible to complete a neg cut on such a vast scale in time to meet the scheduled release date.” But many of the relevant technologies were in their infancy, and the process was often painfully slow. Oliver recalls, “We were unable to watch [the scanned footage] at film speed for a long time because they simply couldn’t process the information at 24 fps, so the process felt a lot longer than it was.” Riddett adds, “There was nothing else to refer to, really, because no one had digitized a whole film.” Today, of course, it’s a very different story, and the cinematographers looked forward to a less pioneering experience in the DI suite for Were-Rabbit. When AC visited them last spring, they had begun digitally grading sequences at The Moving Picture Co. (MPC), and they were in the midst of prepping and shooting the film’s third act, which, in true Wallace & Gromit fashion, promised a spectacular chase. |

|

|||

|

next >> |

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|