KILL BILL • page 2 • page 3 • sidebar MOVE in MOVIE • page 2 • page 3 DVD • page 2 • page 3 |

|

| A

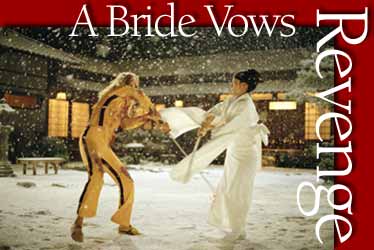

Bride Vows Revenge Robert Richardson, ASC lends his keen grasp of aesthetics to Kill Bill, a genre-blending martial-arts extravaganza. |

||

Unit photography by Andrew Cooper, SMPSP I am first and foremost drawn to the director of a project. The dynamic of this relationship is central. - Robert Richardson, ASC "...even as worn-out clothes are cast off and others put on that are new, so worn-out bodies are cast off by the dweller in the body and others put on that are new." -The Bhagavad-Gita, from Richardson's Kill Bill journal If Robert Richardson tends to describe his filmmaking loyalties in spiritual terms, he has ample reason. His 11-film partnership with Oliver Stone bears mention alongside such other moviemaking "marriages" as Bernardo Bertolucci and Vittorio Storaro, ASC, AIC, or David Lean and Freddie Young, BSC. Though Richardson took occasional sojourns with other filmmakers throughout the 1990s, his compass always spun back to Stone. But that changed in 1997, when a disagreement over the schedule for Any Given Sunday forced the partners apart. Subsequent projects such as The Horse Whisperer, Snow Falling on Cedars and The Four Feathers earned Richardson praise from peers and critics, but have so far failed to yield sustaining relationships. His collaborations with Martin Scorsese (Casino, Bringing Out the Dead and The Aviator, the last of which is currently shooting in Montreal) would seem to indicate a budding partnership, but Richardson says he considers himself a substitute for the director's more frequent cohort, Michael Ballhaus, ASC. As for Stone, Richardson says they have reconciled, but admits that "Oliver has gone on to establish new relationships in other capacities." A Valentine Offer They say you can't expect to catch lightning in a bottle, but this is Hollywood, and bottles have nothing on modern courier service. On Valentine's Day 2002, Richardson opened his front door to a bouquet of roses and a parcel. Inside was the screenplay for Kill Bill, Quentin Tarantino's "chopsocky" opus. Richardson's reaction was swift. "I've never heard Bob more excited than when he started talking to me about Kill Bill," recalls Ian Kincaid, Richardson's gaffer on the show. "You read the script and you immediately think, 'Robert Richardson should shoot this.' You just know that he and Quentin were meant to do this movie together." Indeed they did, and in the months following Kill Bil 's completion, the silver-maned cinematographer would categorically describe the experience as "the purest rhythm I have had with a director - ever." Inspiration

First Impressions Kill Bill's script is an unabashed kung-fu blowout, and Richardson was enthusiastic about its visual potential. Dubbed half-seriously by its author as "the biggest B-movie ever made," Kill Bill pays tribute to all things "exploitation": samurai swordsmanship, Hong Kong "wire-fu," blaxploitation funk, Spaghetti Western standoffs, gangland vendettas, sexy assassins and lots and lots of raspberry-red blood. (In true B-movie spirit, the plot is as cheekily monosyllabic as the title: an underworld boss named Bill double-crosses a hitwoman known as The Bride, who then embarks on a mission to - well, you guessed it.) "One of the first statements Quentin made was that he wanted each chapter of the script to feel like a reel from a different film," Richardson recalls. "He wanted to move in and out of the various signature styles of all these genres - Western, melodrama, thriller, horror. He had an absolute knowledge of what he wanted each sequence to look like." Richardson adds that Tarantino's chapter concepts were so specific and varied that the director initially considered hiring three cinematographers for the project, "but in the end, Quentin decided to hire just one person, probably to help keep things consistent over such a huge production. I had sent him a letter expressing my enthusiasm for the script, and eventually I was chosen." Richardson closed his deal and sidled into a 10-week-long tango with his new collaborator as they prepped the project. "I was patient not to rush for answers," he recalls. "That's a lesson that anyone who wishes to be a cinematographer should take note of." Preparation

Richardson's legendary zeal for visual research continued on Kill Bill. Between the daily shipments from Tarantino's assistants and his own purchases, the cinematographer claims he consumed more than 200 films. These included such genre classics as Once Upon a Time in China, Shaolin Master Killer, Lady Snowblood, 18 Fatal Strikes, Carrie and Coffy, as well as obscurities like Reborn From Hell, Texas Adios, Black Mama White Mama and Deaf-Mute Heroine (one of Richardson's favorites from the bunch). With a bevy of genres to juggle and a globetrotting production to manage - the film was shot primarily in China, but also included locations in Japan, Mexico and California - Richardson admits that maintaining visual consistency over "the sheer scale of the picture" was his greatest concern. He modestly credits Tarantino's elaborate mise en scene (developed in collaboration with production designers Yohei Taneda and David Wasco) with shouldering most of this burden. "The look of this film was primarily decided well prior to my involvement," he remarks. Kincaid, Richardson's gaffer since The Doors, observes, "Bob will give Quentin credit for having lots to say about the film's look, but it's more accurate to say that Quentin really inspired Bob to get the look of this picture going. For instance, when you see a blaxploitation movie, you don't necessarily want to make [your film] look like that, because a lot of them were made at a time when pictures weren't so attractive! Bob's got the ability to look into those films and say, 'This is the essence we have to pull out and use.'" Page

1

|

||