On the Clock • page 2 • page 3 Michael Chapman • page 2 • page 3 DVD • page 2 • page 3 |

|

| Honoring

a (Reluctant) Vanguard |

||

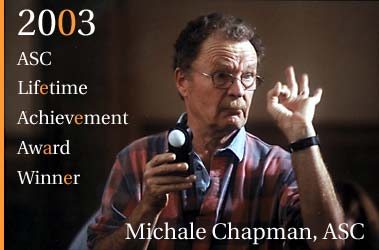

by Jon Silberg Director of photography Michael Chapman, ASC, who will be honored with the American Society of Cinematographers' Lifetime Achievement Award this month, has shot more than 40 feature films, including several from the celebrated American New Wave of the 1970s. Twice nominated for Academy Awards - for Raging Bull (1980) and The Fugitive (1993) - he has also tried his hand at directing (The Clan of the Cave Bear and All the Right Moves) and screenwriting (The Viking Sagas). Chapman's varied contributions to filmmaking might suggest that he spent his youth striving to work in some form of visual expression, but he maintains that his entrance into the film industry was a "complete accident." As a youth in Wellesley, Massachusetts, Chapman was more interested in sports than photography or painting. "I was certainly as passionate about movies as any other kid in Wellesley," he says, "but it never occurred to me that I could go get a job in that business - that movies were made by ordinary people who had families and who went to the bathroom. It was a whole other world to me." After he graduated from high school in the late 1950s, Chapman attended Columbia University, where his major was "useless knowledge," he says with a laugh. "There was a system at that time where you could basically take whatever you wanted and get your degree. I suppose I was an English major or a history major in some vague way." Upon graduating from the Ivy League school, Chapman went to work as a freight-brakeman on the Erie Lackawanna Railroad. "It was a very chic thing to do in the late Fifties - echoes of Kerouac and Ginsberg and all that," he notes dryly. The U.S. Army soon put an end to his railroad career. "This was back when they were drafting middle-class white boys," says Chapman. "Fortunately, it was after Korea and before Vietnam, so I managed to get out of the Army without having to shoot at anybody." After he was discharged, he returned to New York and married a Columbia classmate whose father, Joe Brun, ASC, happened to be an Oscar-nominated cinematographer. Brun, who had emigrated from France, was one of the most respected cameramen on the East Coast at that time. "He was a wonderful guy, but he was scandalized that his daughter should be married to a freight brakeman, so he got me into the [camera] guild. I started out loading magazines on commercials - there were very few features being shot in New York at that time - and I worked as an assistant camera, focus puller, clapper loader and all that." By the time he started working at commercial house MPO, Chapman was hoping to get a chance to move beyond the rank of assistant. MPO happened to employ some major cinematography talents, including future ASC members Gordon Willis and Owen Roizman. Chapman says it was his collaborations with Willis that made him see filmmaking as a passion, rather than just a job. "Gordy was offered a feature, and he asked somebody else to be his operator, but that guy had a chance to work on a series and foolishly turned Gordy down. When he asked me, I changed my card from assistant in a second. Then Gordy took me along for an amazing ride." Chapman operated for Willis on The Landlord (1970), Klute (1971), The Godfather (1972) and The Godfather Part II (1974). After overcoming some initial doubts about operating, Chapman realized that he was good at it, and that it gave him immense satisfaction. "I'd always been a good athlete, and there's a lot of athleticism in operating a camera," he observes. "That's what makes operating so wonderful and seductive and exhilarating to do: it combines athleticism and aesthetics. I loved instantaneous framing and thinking as I went. It was like swinging a baseball bat. It's wonderful fun, it's sexy and it's gratifying. You get to flirt with the actresses. What more could you ask for?" After several successful years, Chapman decided he wanted to be a cinematographer. "I didn't really lobby to shoot anything," he recalls. "I didn't know how to do such a thing - and I still don't. I just hoped that an opportunity would come along, the way the chance to operate had." That's just what happened: Hal Ashby, with whom Chapman had worked on The Landlord, began to prep The Last Detail (1973), and his top choices for director of photography were either unavailable or carried the wrong union card for the East Coast shoot. Ashby therefore decided to let Chapman come aboard as director of photography. "Hal is one of the Seventies directors that people don't talk about enough," says Chapman. "He was really good, and he made some wonderful films. I think The Last Detail is one of the best things Jack Nicholson has done. Besides that, I owe Hal a huge amount; he's the guy who started my career as a cinematographer." As he had with his move up to operator, Chapman approached the transition to cinematographer with a mixture of confidence and doubt. "I was very lucky in that what I was asked to do [on The Last Detail] seemed to almost petition for a certain kind of look. It clearly was meant to look like the 11 o'clock news, and that's what I said to everybody. But the reason I kept saying it was that the 11 o'clock news was the closest you could get to no lighting at all, and I was terrified about my ability to light! I figured there was no way I could light those scenes in a way that would have the power of the light that existed on location." Chapman recalls a fight scene that occurs inside a train station men's room: "We used a railroad station in Toronto, and existing lighting in the men's room was the lighting in the film. I enhanced it a bit here and there so you could see the actors' faces, but that was it." Whereas some cinematographers might want to show off a bit in their first outing, Chapman felt the opposite way. "I wanted to be invisible - which, of course, turned out to be the right thing to want to be. I think The Last Detail is a wonderful movie, and I hope that part of its strength comes from its newsreel/documentary style, which was as much a result of my terror as anything else. Luckily, it happened to work out." Page

1

|

||