|

||||

|

|

|||

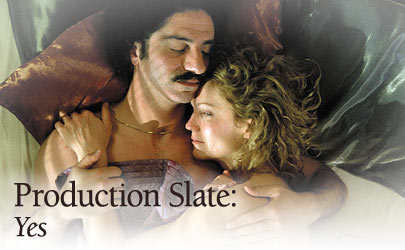

| A Cross-Cultural Romance |

|

|||

Ten years after collaborating on the feature Orlando, Russian cinematographer Alexei Rodionov and British director Sally Potter reteamed for the contemporary love story Yes. The meticulously planned six-week shoot was to begin filming in Beirut, Lebanon, in April 2003, before moving on to London and Belfast. But global politics are even more precarious than production schedules, and when the United States invaded Iraq that March, filming in the Middle East became so dangerous that the production was unable to obtain insurance. The filmmakers decided Cuba was the only viable stand-in for Lebanon, but U.S. government restrictions barred American star Joan Allen from setting foot in the country. Rodionov didn’t bat an eye. Having developed his craft under the old Soviet system, he is accustomed to difficult conditions and is an old hand at improvisation. A graduate of the Film Institute of Moscow, Rodionov started his career in as a television cameraman — shooting film, not videotape. His first feature as a director of photography was Elem Klimov’s Farewell, and his credits include Klimov’s hallucinatory war epic Come and See (which won the Grand Prize at the 1985 Moscow Film Festival), Passion in the Desert (see AC July ’98), and numerous Russian and European productions, including Shtrafbat Moslem, Amidst the Grey Stones, The Kerosene Seller’s Wife and Talk of Angels. Yes chronicles a passionate love affair between an unhappily married American woman who is identified only as “She” (Allen) and a Middle Eastern man identified as “He” (Simon Abkarian). The scenes set in the Middle East include both characters. Abkarian’s scenes and portions of the scenes he shared with Allen were shot in Cuba, while Allen’s half of those scenes — mostly close-ups, medium shots and interiors — were filmed in the Dominican Republic. Adding to the challenges, the low-budget production had such a small crew that Rodionov served as his own gaffer and dolly grip in London. (There were slightly larger crews in Havana and the Dominican Republic.) All of the film’s dialogue is written in verse, some of which is in iambic pentameter, and Potter wanted to bring a similar musicality to the camera movement. “The film was shot mainly with a lightweight dolly on skateboard wheels,” recounts Rodionov, speaking by phone from Luxembourg, where he was scouting locations for his next picture. “It was actually very easy. I pushed the dolly with my left hand while operating with my right hand and watching an LCD monitor. You don’t even need to rehearse with the actors; you just follow their movements.” A bigger problem, he adds, was that he had only four sections of dolly track with which to work. Potter says that the looks of her films tend to evolve during the first week of shooting, but a year before they began filming Yes, she and Rodionov made a five-minute film that employs some of the techniques they used on the feature, including canted framing, jump cuts, speed changes and step-printing. According to Rodionov, many scenes in Yes were filmed at two different speeds — 24 fps and 6 fps for some setups, and 24 fps and 50 fps or 75 fps for others. “Sally decided during editing which speed she would use,” he explains. Given how much film stock would be used, it made financial sense to shoot on Super 16mm. “Shooting Super 16 allowed me to think less about the amount of stock we were shooting,” says the cinematographer. Camera angle was also determined in the editing room. Rodionov shot many scenes on a single angle, but gave Potter and editor Daniel Goddard a variety of angles on others. Framing for 1.85:1, he placed the Aaton XTRprod on a Cinesaddle bag for stability, then tilted the camera up or down or rested it at a skewed angle. At times he held the camera just 2 or 3 feet from the actor and followed his or her face or body movements, often concentrating on an eye, a hand or a pair of lips. Rodionov describes this as “establishing intimate relations between the actor and the camera. You feel that you’re inside the action. I was so close to Joan at times that I could see my shadow in her eye. You must be extraordinarily precise with the lighting, and you must also put up reflectors that are painted with some irregular pattern.” In one scene, he used an 18mm lens just inches from Shirley Henderson’s face as the actress spoke directly to the camera, giving the audience background information about She’s strained marriage. For a scene depicting She’s husband (Sam Neill) in his living room, Rodionov used a 12mm lens and placed the camera on the floor close to and looking up at the actor. The resultant image almost looks as though Neill is standing in a miniature set. Rodionov operated the A-camera while Eric Bialas, using a second Aaton XTRprod, doubled as the B-camera and Steadicam operator. The camera package, which included a set of Cooke S4 primes (18mm-75mm) and two Super 16mm Zeiss lenses (12mm and 9.5mm), was provided by Ice Film in London, the official Aaton dealer in Britain. Rodionov says his choice of Cookes was tied to his choice of film stocks. He shot most of the picture on Kodak Vision 200T 7274 and EXR 50D 7245. “The only high-speed stock I used was Kodak [Vision2 500T] 7218, and that was for a single night scene in a car park that was shot in available light,” he says. “What really surprised me was how much better the image looked with the Cookes. I tried Super 16mm lenses, and it’s not that they were bad or not sharp, but with Cookes, the image looked much more, well, expensive. “We were shooting mostly wide open. Very important for me is how the out-of-focus area of the image looks, mainly the background. The Cooke S4s give you a very beautiful out-of-focus image. You have such depth that you can almost feel the air. They give the image an astounding three-dimensional feel.” Potter, Rodionov and production designer Carlos Conti worked with the premise that each environment was a character with its own color scheme. As the story progresses, the film becomes more saturated with color, an effect that was further accentuated during a digital intermediate (DI) at Digimages in Paris. The colors in the house where She and her husband live are all shades of white and gray — “very stark, like an emotional refrigerator,” says Potter. In He’s apartment, on the other hand, everything is in warm tones. The satin pillows on the bed are gray-blue and red-gold, “complimentary colors on the color spectrum,” notes Rodionov, “so the eye gets very excited going back and forth between the two.” With a laugh, he adds, “We did a lot of fiddling around with those pillows.” The cinematographer gelled his lights with warm hues — Bastard Amber and 1/4 or 1/2 CTO — but he never used filtration on the lens. To make Allen stand out as she lay on the bed, he lit her with a soft white light that was occasionally gelled slightly blue. Rodionov says Allen’s translucent skin helps give her an unusually radiant glow on film. He used only soft light on the actress and made sure it was never frontal. “I never used light in front of the camera for Joan, only sidelight or light from below. It was usually Kino Flos or Miser lights bounced into white or silver reflectors, and a lot of flags. My idea was that the light must be soft but directional, and it should never spill beyond Joan’s face.” For an elegant London dinner party early in the film, lights were hidden along the floor and angled up at magnificent portraits, and hidden on a balcony that was out of frame. “I used open-faced 2Ks through half-white diffusion plus Bastard Amber and 1⁄4 CTO,” recalls Rodionov. “My most powerful light was a 5K bounced into a soft silver reflector.” (The show’s lighting package came from AFM in London.) One of the most intriguing aspects of the film’s visual design is the step printing. “We shot quite a bit at 6 fps, which was then multiplied to normal speed in digital post,” explains Rodionov, who was unable to participate in the post process because of another job. “We even shot sync scenes with dialogue like that. It looks better when the camera is handheld or floating on a Dutch head, which allows you the opportunity of three-axis movement. Although we used Steadicam throughout the film, we never did for the 6 fps work because it would have looked too mechanical.” Rodionov says he was especially pleased by his small crew on Yes, which comprised camera operator Bialas and focus puller Denis Garnier. “Eric is very inventive, made lots of good suggestions about how to do things, and was very pleasant to work with,” he remarks. “Denis has an excellent temper and is also a pleasure to work with — and he is very French, in that he has a very good feeling about aesthetics.” |

|

|||

|

<< prev || next>> |

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|