Compiled by Andrew O. Thompson

Sponsored by:

by Naomi Pfeifferman

Compiled by Andrew O. Thompson

Sponsored by:

The Road to Nowhere | War and Remembrance | The 1999 Independant Spirit Awards | U.S. International Festival

War and Remembrance

by Naomi Pfeifferman

|

| Holocaust survivor Bill Basch and his son, Martin, console one another outside of the Dachau concentration camp during the filming of the documentary The Last Days. |

Soon after arriving at Auschwitz, Renee Firestone found herself standing naked and shivering within the bowels of the concentration camp. Then a teenager, she plucked up the courage to ask a Nazi soldier if she could see her parents. With a sneer, the conscript pointed to the plume of thick black smoke belching from the crematorium's chimney.

In The Last Days — the third documentary from Steven Spielberg's Survivors of the Shoah Visual History Foundation — Firestone and four other Hungarian Holocaust survivors return to the hometowns and concentration camps where they suffered during World War II's final weeks.

Combining rare archival film footage, still photographs and survivors' testimony, the documentary describes a little-known chapter of Holocaust history. "The war was essentially over for the Nazis when they invaded Hungary in 1944 and launched a full-scale genocide, going so far as to even sacrifice their own war efforts to carry on 'The Final Solution,'" explains director/editor James Moll, a founding executive director of the Shoah Foundation.

The feature-length film is filled with poignant pieces of personal memory: Firestone remembers the five-day train ride to Auschwitz — in a cattle-car crowded with 120 people — without food, water or bathroom facilities; Irene Zisblatt recalls her incarceration in a dark, wet dungeon, where she endured a Nazi medical experiment; artist Alice Lok Cahana speaks of celebrating the Sabbath in the Auschwitz latrine; businessman Bill Basch describes a wintry death march; and U.S. Congressman Tom Lantos reflects upon the dangers of working for the underground in Budapest. Other interviewees include a former Nazi physician, three American veterans who helped to liberate Dachau, and a former Sonderkommando — a concentration camp inmate forced to clear and cremate bodies from the gas chamber.

Distributed by October Films, The Last Days is the first theatrical release by the Shoah Foundation, which Spielberg created in 1994 to videotape and archive testimonials from more than 50,000 survivors. The Foundation has also produced a CD-ROM and two acclaimed TV documentaries — the Emmy Award-winning Survivors of the Holocaust (see AC January '96) and The Lost Children of Berlin.

Before Moll started up the Foundation with Last Days producer June Beallor, he wrote, directed and produced dozens of educational and promotional films on various social issues, such as aging and the environment. In the Foundation's early days, Moll called on his old USC film school chum, cinematographer Harris Done, to shoot the first test interview with a survivor. Last year, when the Foundation embarked upon The Last Days, the director once again recruited Done, who has photographed some 20 independent films, including Ocean Tribe (see L.A. Indie Fest coverage in AC June '97) and the quirky documentary Trekkies (AC Jan. '99).

While Moll and his research team perused Foundation archives for five diverse Hungarian subjects, he and Done made the decision to film Last Days in 35mm, even though much of the documentary would have to be shot handheld. "James and I went over to Technicolor, where they had lined up a 'Super 16 versus 35mm' test for us," says Done. "On the one hand, I thought, 'There is no simple way to travel with 35mm gear. The camera package alone is going to fill 28 cases, which we're going to have to tote from Munich to small towns in the Carpathian Mountains. The camera will take longer to reload, it's going to weigh about 45 pounds, and I'm going to take the brunt of the abuse.' On the other hand, both James and I realized that when the survivors were telling their stories, when they were feeling things, the detail in their faces would be vivid. In Super 16mm, there's just not as much resolution, and the wider the shot, the less information you see."

Since historical integrity was a top priority, Moll opted against the use of narration: he wanted the piece to be formed around personal testimonies. For accuracy's sake, he also refused to use staged "representational" footage. Instead, his researchers scoured archives worldwide for accurate visual depictions of the survivors' specific stories. Moll expands, "Once we determined which images we wanted to include in the film, we ordered copies in 35mm, if they were available, or in 16mm, which Pacific Title bumped up to 35mm. Then we had to deal with all of the cropping and aspect-ratio issues to be able to deliver both a theatrical and a TV version — it was a nightmare."

|

| Cameraman Harris Done shoots Congressman Tom Lantos with his grandchildren as they walk along a bridge in Hungary where Lantos toiled in forced labor during the Holocaust. |

Cinesite did a great deal of stabilization and restoration work on reams of shaky and damaged archival film. However, some of the most gripping historical footage turned out to be in perfect shape — the son of an American World War II veteran had contacted the Shoah Foundation about some footage which had sat untouched, for decades, in his father's home. The never-before-seen clips turned out to be rare 16mm color images of skeletal Holocaust victims photographed after the liberation of Dachau.

With such haunting illustrations at his disposal, Moll did not want style to overshadow content, so he opted for realism. Done therefore avoided heavy lens filtration, sizzling hot backlights and zoom moves during interviews. Instead, he employed five different images sizes — pre-marked on the Panavision 10:1 (25-250mm) T4 and 5:1 (20-100mm) T3.1 zoom lenses — to correspond to five distinct interview topics. Because the documentary relates the survivors' tales in chronological order, the images become tighter as the drama intensifies.

During the 4- to 6-hour interviews conducted with survivors in their Stateside homes (conducted in July of 1997), Done utilized two Panavision GII cameras with 1,000' magazines to allow for 20 minutes of continuous shooting. Lighting these oral histories was always an exercise in naturalism. While in Houston, Texas, shooting a conversation with Alice Lok Cahana, for example, the cinematographer used "a 575-watt HMI Par with a Chimera to create a big, soft key light, further controlling the look with two 'floppies' — rolls of black Duvateen hanging off of C-stand arms." He then backlit his subject with an 300-watt HMI Joker aimed through a mini-Chimera, and made subtle use of Tiffen Black ProMist filters — no more than 1/4 to 1/2 in strength — to give the elderly survivor a softer, more flattering look.

In August, the filmmakers embarked upon the grueling, 10-day European shoot. Done brought along a GII, an Aaton 35-III, a set of Primo primes, a Canon 150mm-600mm T6.3 zoom, and a small lighting package consisting of a 575-watt HMI Fresnel, a 300-watt HMI Joker and a lightweight Lowell tungsten kit. All of the equipment had to make the transition to 220v to function with European currents. He also brought along a variety of Eastman Kodak stocks: 100 ASA EXR 5248, 200 ASA EXR 5293 and 500 ASA EXR 5298.

|

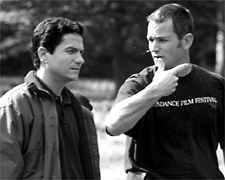

| Director James Moll (left) and Done discuss a setup at the site of the Bergen-Belsen camp's mass graves. |

While shooting handheld in locations such as the vast Auschwitz camp, Done shouldered the GII instead of the more lightweight Aaton, since the latter camera's 400' magazines allow for only four minutes of uninterrupted filming. When shooting handheld, Done preferred the 21mm Primo prime, which permitted him to play shots a little wider for the big screen. "The 21mm is a very flat lens, which meant that I could get very close to a subject without distortion," Done adds. "I love shooting close-ups of people with a wide lens, because it allows you to feel the space they're in."

In a small town outside of Munich, Germany, Firestone visited a former Nazi doctor who is believed to have performed medical experiments on her sister at Auschwitz. "The tension was thick in the room," says Done, who only had the use of one GII for that sequence. "Rather than panning back and forth between Renee and the doctor, James and I decided on a two-shot to capture the body language, and to let the tension play between the two."

When funding ran low for shipping expenses, the crew sometimes stashed equipment in their personal luggage while traveling through Poland, Hungary, Germany and the Ukraine. Fortunately, Panavision, Technicolor and Pacific Title donated almost all of the equipment and covered lab expenses.

Though the extensive traveling left the crew weary, the shocking subject matter they encountered exerted an even greater toll upon them. "Most of the crew members had never before heard a survivor give testimony, and they were often moved to tears," recollects Done. "I remember once looking at my assistant while we were reloading, and he was just shaken. One of the most devastating interviews, for me, was the one with the former Sonderkommando, who told us about finding two of his old friends in line for the gas chamber. All he could do was give them some bread and tell them where to stand in the chamber so they would die quickly. When you hear these terrible stories, you try to put up an emotional barrier so you can function, but it doesn't always work."

Needless to say, the crew members weren't the only ones left with emotional scars. While shooting at Auschwitz, Alice Lok Cahana instinctively shouted at Moll to stay away from the barbed wire fence, which during the war had been electrified to deter would-be escapees. Despite suffering exhaustion after countless 19-hour days, the crew remained reserved and respectful. As Done notes succinctly, "There is no complaining at Auschwitz."

The filmmakers faced a different set of challenges when they traveled to the hometowns of Renee Firestone and Irene Zisblatt, which are located in what is now the Ukraine. "We were advised to keep our American crew and Panavision equipment behind, because robbery, kidnapping and other Mafia activities are rampant in that part of the former Soviet Union," says Moll. "We were told to hire a Russian crew and to avoid wearing blue jeans or speaking English in public."

Eight stone-faced, armed security guards, clad in dark suits, followed the American filmmakers everywhere, even to the bathroom. Each night, the men stood guard in the hallway outside of their hotel rooms. Though a squad of men in black might seem an overcautious measure for a documentary crew, their presence did not prove unwarranted. One morning, the crew woke to the news that some Mafia types had raided the hotel that night in search of the Americans. In another instance, a group of menacing thugs surrounded the crew just as the director had lined up a shot at a street fair. "Our Russian coordinator came up to us and whispered, 'Grab the camera and get in the car.'" The filmmakers did so, but not before quickly nailing the shot.

As if all these distractions weren't enough, Done had problems of his own. With his hand-picked equipment unavailable for security reasons, the cinematographer had to make do with a poorly maintained Arriflex BL and a set of Zeiss lenses rented from an equipment house in Moscow. His Russian crew, meanwhile, spoke barely a word of English. "I learned that in Russia, crew members' various jobs are different than in the United States," says Done. "When I turned to the first assistant and said, 'Let's reload,' he looked at me blankly and said, 'I don't reload!' In the Russian system, the first assistant only pulls focus and takes light-meter readings. The technician who does reload was off loading other magazines, so I just did it myself."

Regarding the rented Russian equipment, Moll recounts, "The camera was this old hunk of metal that was so loud I couldn't believe it. You can actually hear it in one scene where Irene is talking about going back to her hometown. I cringe every time I see that sequence. Also, the head on the tripod was the furthest thing from smooth that you could ever imagine. We took it back to the Russian equipment house, but they gave it back to us and said, 'We tested it, and it's perfect!' Of course, the head on the tripod was still jerking. I had to edit around the jerky pans. In the end, I was relieved to find that we actually had an image when the film came back from the lab!"

The closing shot of The Last Days is the documentary's most lovely and haunting image. Using a 27mm Primo prime, Done captured a close-up of three "yarzeit" memorial candles that Firestone had placed on the ruins of a crumbling Auschwitz crematorium. As the sunlight wanes, moths flutter about the flickering candles. "It was the end of the day; the film rolled out, and we didn't have any more left," relates Done. Since the image ran for only eight seconds, Moll doubled its length by double printing each frame in the lab, and adding a long fade-out. This ethereal portrait will always have a deep meaning for Done. "After we had been on the journey with Renee and the other survivors, we really knew what those candles represented.

© 1999 ASC