|

||||

|

|

|||

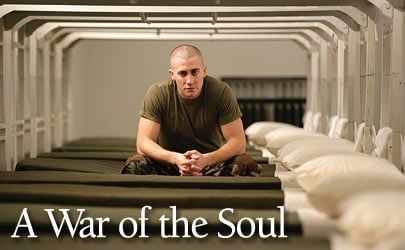

To further emphasize the film’s realistic tone, Mendes sought to lend the images a certain raw look. Grain and contrast were appropriate, but just how much became a matter of discussion. Deakins tested a variety of possibilities: pushing the stock, using bleach bypass, pushing it more in the digital intermediate (DI). “As much as anything, I think it was Sam feeling his way visually, because now, we’ve pulled back quite a bit from that original, harsher look,” says Deakins. “It’s still harsh — we still have grain and the contrast is enhanced — but it’s not as extreme as when we were testing. I think that’s good, frankly, because if you go too far with that type of look, it can seem too self-conscious. But we still pushed things, like in the desert scenes; it kind of hurts your eyes when you go from a dark tent interior into this bright, blinding desert.” To attain the desired look, Deakins applied a combination of 500T stock, partial bleach bypass on the negative, and a light touch during the DI color correction. Working with an Arricam Lite and Cooke S4 prime spherical lenses, he shot the entire film — even bright desert exteriors — on Kodak Vision2 500T 5218 for uniformity of grain. But he didn’t worry about desert backgrounds blowing out, which sometimes surprised the crew. Gaffer Christopher Napoletano was fully expecting to pull out some diffusion or bounce, especially for scenes involving Jamie Foxx, who plays the battalion’s Sgt. Siek. “As dark as Jamie is, I thought we’d have to lift him up with a little bounce light, but Roger said no,” Napoletano recalls. “We didn’t do any lighting for 95 percent of our day exteriors; they were all natural, and we very rarely used diffusion. In fact, we laughed about it, because when we got out in the desert, there wasn’t much for us to do.” “I was going for a bleached look,” Deakins explains. Since the film was shot in southern California and Mexico during the winter months, the film stock’s speed of 500 ASA was less of a problem than one might imagine. In fact, “I was generally shooting at f/5.6 or f/8, only rarely at f/11 or deeper,” says Deakins. “Because I was giving [the stock] so much exposure and letting the sunlight go hot, it was reading the shadows quite well.” Even though the mission plan called for grain, Deakins wanted a sharp, clean image. He therefore abandoned early thoughts of shooting in 16mm, and of force-developing the stock. Force-developing felt too soft, without enough “snap,” whereas bleach bypass provided the right kind of texture. “We did a partial bypass because I knew I was going to go further on the DI,” he notes. “Still, I wanted to have enhanced contrast and desaturation to start with, and I also wanted the kind of grain the bleach bypass was going to give me — something you can latch onto in a DI.” Testing helped Deakins determine the degree to which he would augment the grain during the DI. “EFilm had worked out a program where you could actually add grain as an overlay, in a way that looked totally organic to the image,” says Deakins. “It was amazing to see. But in the end, I think Sam thought it was too much, and we didn’t go that far.” However, the cinematographer did argue strongly for a 4K scan. “That may seem strange, considering that I wanted a more raw image. But I did some tests, and the 4K actually makes the grain feel sharp.” Another key to Jarhead’s visual design was the indelible wartime images of Kuwait’s burning oil fields, set alight by retreating Iraqis. Swofford marched right through those fires, and they are a vivid presence in the book: “The flames shoot a hundred feet into the air, fiery arms groping after a disinterested God. We can also hear the fires, and they sound like the echoes from extinct beasts bellowing to reenter the living world,” the author writes. Those fires are a constant presence from the time Swoff’s battalion reaches the border until they enter Kuwait City. When the towering columns of flame aren’t in view, their presence is still felt — in the petrol rain, the billowing black clouds of smoke that blot out the sun, and in the flickering orange glow reflected in the sky and sand. Recreating these effects throughout the third act was one of the primary tasks of the lighting and effects departments, who used a combination of stage and practical locations, as well as real and CGI fires and smoke. The work began with tests on Universal’s largest soundstage, Stage 12, where an extended twilight-to-dawn sequence would be shot. By this point in the story, the troops have moved beyond the flaming fields and set up camp for the night. “I chose to do that sequence on stage, because we wanted to get this feeling that they were in this thick smoke, in a kind of limbo,” says Deakins. “I tested to determine how big a stage we would need and how I could light it as though the light was a long way away.” He also wanted to be able to shoot in 360°, a requirement for most of his lighting schemes due to the handheld camerawork. In helping Deakins achieve these goals, the crew prepared a large black cyc that had a slightly grayer horizon line. The cinematographer explains, “I lit through the back of the cyc in a couple of places to make it seem as if very distant oil fires were lighting the horizon line, and to give as much depth as possible.” To create this effect, Deakins employed 2K Blondes controlled by dimmers and gelled with Full+1⁄2 CTO. The flames themselves would be CGI effects created in post by Industrial Light and Magic. To the side of the cyc, the crew rigged up a rolling apparatus that provided soft, flickering flame-light. This rig was created from a series of 8' batten strips with porcelain sockets (“We built hundreds of them throughout the show,” notes Napoletano), each loaded with about ten 175- or 500-watt mushroom globes, or R40 flood lights, wrapped in full CTO and wired to three circuits on a dimmer board. “These were like a long strip of soft light, and I would gang them up on a circular pipe,” says Deakins. “We cut a pipe in an 8-foot half-circle and put these battens vertically on the circle to create a soft unit that we could roll around and send out light in a full 180-degree spread. The rig gave us a soft, glowing light that was flickering and very alive.” |

|

|||

|

<< previous || next >> |

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|