|

||||

|

|

|||

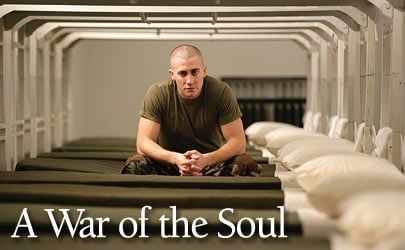

At the center of the bowl was a large bonfire that lit the immediate surroundings. Behind it, the crew positioned some 1,000-watt, dimmer-controlled FCM Nooklights to augment the natural firelight. Napoletano explains, “There was a wide area on the back side [of the bowl] that needed a little help, and simply raising the intensity of the fire wouldn’t have looked right.” Deakins further refined the look of the scene with another idea. To differentiate the lighting in the center of the encampment, he suggested parking a few Humvees with their headlights on. “The vehicles weren’t really lighting much,” the cinematographer explains, “but every now and then a figure would walk through the white light of the headlights, rather than just through the gold firelight.” For close-ups of the sniper team cresting the dune, Deakins again turned to batten strips and his favorite method of lighting: using multiple small sources to provide a soft light that wraps around the subject. Several 8' strips of gelled mushroom bulbs were laid end-to-end a foot off the ground, sidelighting the actors with a soft, flickering wall of “firelight.” This multiple-source wrap light was also used in interiors. The same principle applied, whether the filmmakers were lighting through the windows of barracks or reflecting off sand outside a tent, using bounce cards or lighting through diffusion. “I tend to make a sort of ring,” Deakins explains. “The lights that are placed at three-quarter side to the character might be the hottest, and as they come around to the front, they get progressively dimmed down, creating this soft wrap of light. It’s what I like to do.” One variation of this approach was applied for a scene set in a movie theater, where the soldiers watch the film Apocalypse Now to get psyched for battle. Instead of throwing a light on the audience using a large single source, Deakins placed 45 Tweenies overhead in a triangular arrangement, with the apex at mid-audience. Some of the lights were gelled blue, others stayed at 3200°K, and all were wired to a dimmer board programmed to replicate the changing light intensities of the projected movie. “I first used this type of grid on O Brother, Where Are Thou? when we were shooting in a Mississippi theater,” Deakins recalls. “It was a protected historical building with a very low ceiling — I had no more than a foot between the top of frame and the ceiling in which to rig lights.” In Jarhead, by graduating the light’s intensity and reducing it toward the edges, he generated a soft, pulsating wash over the audience. Deakins worked hard to vary his lighting throughout the film. For tent interiors, he created different daytime looks by raising and lowering the tent flaps and manipulating bounce light. At night, he lit one scene using just two bare lightbulbs, each backed by a small 100-watt quartz gag light. The cinematographer also made use of hard lights and bold shadows. “People say I always use soft light,” he notes. “Well, I don’t. I love using hard light.” As a recent example, he cites the night scenes in Intolerable Cruelty. In Jarhead, this harder look was employed in a dream sequence lit with open-faced HMI sources. Swofford rises from bed, walks into the barracks bathroom, and vomits sand into the sink. “Roger wanted the barracks to look dreamy and disorienting, with a very sharp crisscross pattern created by the windowpanes,” says Napoletano. Rather than a moonlight look, Deakins sought to light the scene with a sodium-vapor feel. The gaffer elaborates, “When we did the wide shot, we put some of the new Alpha 4K X Lights and some Arri 6K X Lights on Condors outside the windows to make this very sharp pattern on the floor.” Deakins says he started with one row of lights, “but that looked too ordered and boring. So we began to use more lights to generate arbitrary patterns on the walls, and I started building the look that way.” When the scene moved onto Stage 12 for the bathroom set, they repeated the approach with open-eye Fresnels etching patterns through the windows’ security screens. For every scene, Deakins drew up detailed lighting diagrams. Some were sketched on art-department set plans, but most were freehand drawings. “They were idiot-proof,” remarks Napoletano. “That guy can really draw.” Now on his fourth feature with Deakins, the gaffer has been impressed with Deakins’ degree of preparedness since their first picture together, House of Sand and Fog (see AC Jan. ’04). “On that show, Roger handed me a stack of notes, I went and rigged everything to his notes, and nothing ever changed, which seemed really unique,” says Napoletano. “He had everything down to exactly how many lights he wanted somewhere, and he used every one of them.” Says Deakins, “By the time we come to shoot, I’ve got a whole file on every location, and scene breakdowns and lighting diagrams for everything. Not that I necessarily stick to them, but they’re a good place to start. I’m one of those people who thinks the more organized you are at the beginning, the more freedom it gives you to play around when you’re on set.” This approach was critical on a film like Jarhead, since its handheld camerawork necessitated 270- or 360-degree lighting. “You’re lighting for a number of angles, for flexibility. It’s not like you’re going from one shot to another, and you’ve got lots of lights on the floor.” From Napoletano’s vantage point, Deakins is one of the most hands-on and mechanically inclined cinematographers around. “I sometimes joke that I’m going to get him a pair of gloves, so if he ever loses his day job, he can come work with me,” says the gaffer. “Where other cameramen wouldn’t attempt something [mechanical] because they might fumble around, he would do it. He has a lot of ideas and builds a lot of his own gag lights.” |

|

|||

|

<< previous || next >> |

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|