KILL BILL • page 2 • page 3 • sidebar MOVE in MOVIE • page 2 • page 3 DVD • page 2 • page 3 |

|

Page

2

|

||

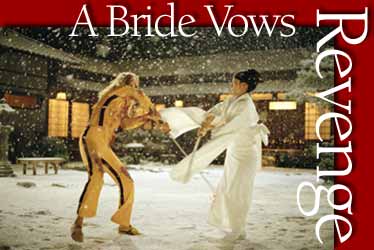

Richardson's own explanation bears this opinion out: "What I'm going after in [any genre] is what that genre represents: the attitude toward the filmmaking, rather than the filmmaking itself. Take Spaghetti Westerns, for example. How would you describe the fundamental differences between a John Ford film like Stagecoach and a Sergio Leone film like Once Upon a Time in the West? It's in the angles, the characters, the sensibility that the filmmaker has toward his subject. I consider Leone a master, and his attitude is part of the Spaghetti Western essence that Quentin was after for certain parts of Kill Bill. When he wanted that particular kind of close-up, with a very specific angle and a very specific size, he'd say, 'Give me a Leone,' and I knew exactly what he meant." Richardson did design a specifically "textural" look for a sequence in which a wizened monk (Gordon Liu) helps The Bride (Uma Thurman) sharpen her fighting skills. "Quentin wanted to replicate the visual generation loss in these old kung fu films - the scratches, the higher-than-normal contrast," he explains. Instead of attempting to create the effect digitally, Richardson employed a photochemical process. He began by capturing the action on contrasty Kodachrome color-reversal stock. He processed that normally, struck an internegative from the print and then struck an interpositive from that, and so on. "We just kept making dupes and prints back and forth until Quentin was happy with the look," he says. He used six other Kodak stocks for the rest of the film: EXR 5248 and 5293; Vision 320T 5277, 500T 5279 and 800T 5289; and 5222 for black-and-white sequences. Consideration

Richardson says there was never any debate about how to obtain Kill Bill's widescreen aspect ratio. The production filmed in the Super 35mm format using Richardson's preferred Panavision Platinum cameras, fitted with Primo lenses and configured for 3-perf shooting. Nevertheless, both Richardson and Tarantino had lingering reservations about maintaining visual fidelity in the oft-maligned format, citing traumatic experiences on Casino and Reservoir Dogs, respectively. Unable to screen first-generation prints, Richardson considered the next best thing: a digital intermediate (DI), executed at Technique. "This is the best approach available right now, and it'll only get better," he observes. "There's no reason it shouldn't become the mainstream way of doing things." But convincing Tarantino wasn't so simple. As leery as the director was about Super 35, he was even more wary of anything labeled "digital." "Quentin doesn't like that word," Richardson says. "I'm still intimidated by [digital timing] in some ways myself. It's like putting me in the cockpit of a 747: what the hell am I going to do besides put it on autopilot? But as you learn, you do become less intimidated, and you can do things that are simply not possible photochemically. In this particular case, I saw the DI as the best way of maintaining control over the imagery, which is why Quentin finally decided to go with it." However, shooting with a DI in mind was another story, and Richardson soon encountered the limits of his director's magnanimity. Simply put: Tarantino doesn't test. "Actually, his words were 'Testing is for pussies,'" the cinematographer reports. "He believes you should be willing to make errors and enter into those errors on the day. And I believe there's a good deal of truth to that. If you're willing to take a risk, there's more to come from it. "On the other hand," he continues, "we were doing a lot of things none of us had ever done. I'd never rendered something back out to film before, so I wanted to know how far the texture of this world should go: the details, the subtlety of color, what the quality level would be compared to something [printed] straight onto film. But mostly, my great fear is faces. For any actor I'm going to work with, I really want to know his or her face before I put it on film." After "begging, basically," Richardson was granted two-thirds of a day for tests. "Even though I had a wide array of images over the five-minute test I did, I still don't know exactly what I can do when I get to the final [output]," he says. "I essentially went off of the level of knowledge I'd gained from shooting commercials, hoping that the majority of it will apply. Where it doesn't, I know that my knowledge of film craft will back me up." Production

Kincaid has worked everywhere from Thai swamplands to Vegas casinos, but he admits he had no idea what to expect from the Mao-built Beijing Film Studio. "We sort of thought that it would all be put together with bamboo and who knows what," he jokes. Though that was hardly the case, the filmmakers still had to do plenty of what Richardson calls "assimilating" during their three-month stay in China. "The idea is to accept another's way of approach," he says. "All of [the Chinese] attitudes are distinctly different from yours and mine, from what's important in their lives to how they make their own films. You have to become accustomed to how they move their gear, how they set up a stage, what they believe functions and doesn't function, who's responsible for what job. Shooting there brought [the film] a textural sensibility that would have been extremely difficult to attain in Los Angeles." The production's budget had a longer reach there as well, especially in terms of manpower. "I've never been on such a crowded set in my life," says key grip Herb Ault. "I had at least twice as many grips in my crew than usual. Everybody's supposed to be equal in a communist society, so they all kind of swarm and get stuff done by sheer number. It got to the point where I just couldn't get in the way. I would have to tell my translator what I wanted done, and step back." Cinematographers, however, take direct communication with their crew for granted, and Richardson found the process especially cumbersome. "I come with a high passion to make something, and I expect everybody else to have that same passion. But you have to enjoy a certain level of communication to get that across, and because few spoke English and I didn't speak Mandarin, there was a constant level of frustration." Page

2

|

||