KILL BILL • page 2 • page 3 |

|

page

3 |

||

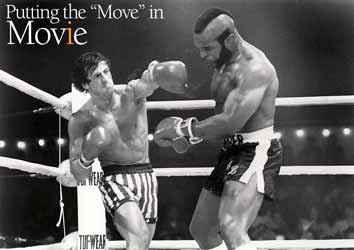

Such economy hasn't always been in great supply. Roizman famously expanded and refined camera-car movement in The French Connection (1971), but that film's justly celebrated chase inspired countless others, with steadily diminishing returns. In addition, new ways of achieving more kinetic movement kept being developed. Devices such as the Louma crane increased the camera's ability to travel where no camera operator had gone before. This French device was brought to the U.S. for 1941, the 1979 comedy shot by Fraker and directed by Steven Spielberg. (Romanoff was the show's camera operator.) At about the same time, of course, Brown's Steadicam made a revolutionary impact on such films as Rocky and Bound for Glory, the latter of which earned Wexler the 1976 Oscar for Best Cinematography. "Haskell understood before we did that it would be a good replacement for a dolly shot over ground where you couldn't possible dolly straight ahead or straight back," says Brown. While the Steadicam was more direct than a dolly, it was far more controlled than a standard handheld move. "I think it's very close to getting to the essence of what a moving shot's all about," says Brown. In The Shining (1980), Kubrick's penchant for endless takes allowed Brown to perfect the use of the device, and to achieve the famous "controlled float" in the film's moving shots. Brown writes, "For nearly a hundred years, backing up ahead of oblivious characters in scary places has made movie audiences nervous, but the relentlessness and, I think, the oily smoothness of Stanley's camera cumulatively made the vast cold environs of the Overlook feel dangerous throughout." Fraker believes the Steadicam has had as much impact on the way movies are made as the introduction of sound and the arrival of television. But the ubiquity of the Steadicam in the age of the music video is part of what caused Brown to consider the issues he does in his Zerb article. "Why move the camera?" he posits. "The reasons range from the very most primitive (the simple 3-D effect) to the most absurdly complex (intersecting dramatic, kinetic, psychological and optical possibilities), which suggest that the most important thing to know is when to stop!" "Somebody will say, 'Let's move the camera,'" says Roizman, speaking of the type of director who came of age after 1980. "'Okay, why do you want to move it?' 'I don't know, let's just move it.' Well, that doesn't make sense to me. I usually like to hear a reason, or feel a reason." Adds Wexler, "So much contemporary film and television is involved with getting people's attention. The fascination with the details in the technology and tools has prevented many contemporary filmmakers from exploring better ways to impart visual drama." Fraker decries the use of camera movement "just to create some energy in a scene that has no energy." To Romanoff, the issue of energy is both crucial and elusive: "People become enamored of the idea of the big crane shot or the big Steadicam shot, and they lay out two minutes' worth of move that runs out of emotional energy after about 30 or 60 seconds." But even amidst all the uninspired camera moves, the great, exhilarating ones still turn up. A memorable example is Larry McConkey's Steadicam shot of Ray Liotta and Lorraine Bracco entering the Copacabana in Goodfellas (1990), shot by Michael Ballhaus, ASC and directed by Martin Scorsese. The camera stays behind the pair as they enter the club's rear entrance and move through the kitchen and various service areas, where everyone knows and greets Liotta's character. Says McConkey, "Several times I would get to a moment when I felt the shot was starting to die, so we'd bring in another character for Ray to interact with." As the shot reaches its climax in the club's main room, a table is set up for the couple near the stage. Writing about this shot, Brown notes that in the hands of Scorsese, Ballhaus and McConkey, the Steadicam became a very different instrument than the one used on The Shining. In the Goodfellas sequence, he says, the device is "disarming and cheerful and entirely about the careless power of Ray Liotta and his mobster pals." McConkey says, "I deliberately tried to take on the role of an audience member and behave as a surrogate character that responds on their behalf. I thought of myself as a tour guide driving a bus, a sports car or a boat, gently leading the audience to anticipate a turn or surprising them with a sudden curve." A more recent invention, the Akela crane, allowed John Toll, ASC to obtain some unusual, low-to-the-ground shots that moved through the tall grass of a Guadalcanal battlefield in the World War II drama The Thin Red Line (1999; AC Feb. '99), directed by Terence Malick. "The whole idea of using that crane was to not make it feel like a crane," says Toll. "We wanted it to look like the most continuous, smooth dolly that had ever been built." The 85'-long Akela arm "is so long that it really minimizes the arc of the move; you can actually make it feel like you're traveling in a straight line," he adds. Romanoff observes, "In those shots, the camera isn't used apart from the actors to tell the story. Welles takes a crane and uses it to move from story point to story point, but you're always aware somebody is taking you on the trip. In The Thin Red Line, the camera doesn't rove from place to place, so it doesn't call attention to itself as a crane move." Brown acknowledges some professional jealousy over Russian Ark, whose makers managed to sustain an 86-minute Steadicam shot (AC Jan. '03). However, he also feels the illusion of movement has become too easy to achieve in the digital era. He writes, "There is something about the klutzy dolly and crane shots in classic movies that comparatively resonates - something physical. They felt more important, more meaningful!" Adds Fraker, "The young filmmakers, God bless them, all want to do the greatest camera shot that's ever been done, regardless of what it has to do with the picture." For his part, Romanoff believes camera movement is all a matter of style, with each example as legitimate as the next. "From my point of view, there's no such thing as too much movement unless it doesn't serve what you're trying to accomplish. When MTV started to happen, a lot of my friends were saying, 'This is terrible, it's so overused,' but I was saying, 'No, this is really cool.' If you only love Dixieland jazz, then you're going to find it hard to love a great blues performance. I happen to like a lot of different music." page

3

|

||