KILL BILL • page 2 • page 3 |

|

| Putting

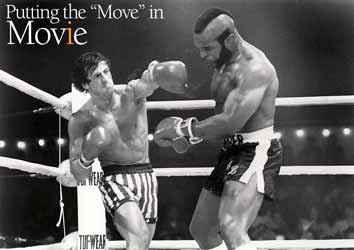

the "Move" in Movie Prominent cinematographers and industry experts consider the aesthetics and psychological implications of camera movement. |

||

The "hows" of camera movement - the technology and techniques whereby camera operators, cinematographers, and directors can create moving shots in a film - are easy enough to identify and define. It's when you start trying to talk about the "why" and the "when" that the discussion gets vague and a bit complicated - as hard to pin down as the famous tracking shot that opens the noir classic Touch of Evil (1958).The impulse toward movement is not hard to understand; we are, after all, talking about motion pictures. But if you don't want to be indiscriminant in moving the camera, questions arise: When is it called for? When should it stop? And what does a camera on the move mean to the spectator? "My philosophy is, good camera movement happens when you're not even aware of it," says Owen Roizman, ASC. "It just feels right. My approach has been to always let my instincts, the scene and what the actors are doing dictate whether or not the camera should move." For William A. Fraker, ASC, it's all about story: "Camera movement's great, but it's got to be about exposition. You have to involve the audience visually, but to do that, you don't need fancy movement and 360-degree dolly shots." According to Haskell Wexler, ASC, "Camera movements are used to lead the eye, to give people a feeling - an emotional one, a logical one, a dramatic one - just the way lighting and framing are." In fact, both Wexler and Roizman maintain that camera movement can't be considered separately from those other key elements of a cinematographer's art. John Toll, ASC, puts it succinctly: "The shot has to fit into the overall visual design of a film to have impact." Still, it is movement that makes a movie a movie. Other visual arts are lit and composed, but only in cinema (and its video offspring) does the ability exist to reframe a continuous image. And ever since 1896 or so, filmmakers have been looking for ways to do so. In 1916, D.W. Griffith and cameraman Billy Bitzer created what is one of cinema's earliest camera moves: the slow, simultaneous track in and down on the massive Gates of Babylon set in Intolerance. The obvious reason for the shot was to first establish the scale of the set, and then to move closer to verify that actual human activity was taking place in it. This is what Steadicam inventor Garrett Brown refers to as "the 3-D effect." In an excerpt from an upcoming series of articles on "The Moving Camera" for Zerb: Journal of the Guild of Television Cameramen, Brown explains, "When the camera begins to move, we are suddenly given the missing information as to shape and layout and size. The two-dimensional image acquires the illusion of three-dimensionality and we are carried across the divide of the screen, deeper and deeper into a world that is not contiguous to our own." As the silent era reached its apogee in the 1920s, artists around the world were finding new ways to incorporate camera movement into the grammar of film. In the Soviet Union, Sergei Eisenstein was doing pioneering work with montage; in Germany, F.W. Murnau was experimenting with other methods of telling a story through purely visual means. Murnau's 1924 film The Last Laugh, shot by Karl Freund at Ufa Studios, is so visually expressive that it contains not a single intertitle. In one sequence, the camera was operated from a bicycle, and in another, Freund strapped the camera to his chest to simulate a drunken character's point of view. When Murnau came to Hollywood to make Sunrise in 1927, he imported his roving style, working with cinematographers Charles Rosher, ASC and Karl Struss, ASC to unleash the camera from its bonds. During his audio commentary on the recently released DVD of Sunrise, John Bailey, ASC lovingly describes what he calls "one of the most famous shots in all of silent film." The lead character, a farmer played by George O'Brien, walks into a swamp at night to tryst with a licentious woman from the city. As the farmer moves through the foggy set, Bailey details, "The camera is following him, not on a dolly, but on an overhead track with a platform suspended from it." O'Brien moves in a more or less figure-eight pattern, followed by the camera; the stalking movement mirrors the farmer's compulsive entry into dangerous psychological terrain. For another famous sequence in Sunrise, the filmmakers placed the camera on a trolley that appears to move continuously on tracks from a country location to the city, which was built on the Fox lot. Murnau and his cinematographers were always looking for reasons to free the camera, whether to express an emotion (as in the swamp scene), or to get the characters from point A to point B in an eloquent way (the trolley scene). French director Abel Gance was another filmmaker for whom "the tripod was a set of crutches, supporting a lame imagination," writes Kevin Brownlow in his book The Parade's Gone By. Recalling Gance's biggest production, Napoleon (1927), which was shot by Jules Kruger, Garrett Brown marvels, "There are things in Napoleon that are so ahead of their time. [Gance] stuck the camera on every possible type of vehicle; he did things in that film that weren't taken up again for 30 years." However, everything seemed to change when movies began to talk. The demands of technology and recording dialogue started this transformation, and the "invisible" classical style that soon developed finished it. The odd talent like Busby Berkeley was still devising means to move the camera between a grouping of dancers' legs, and a stray crane shot - such as Scarlett O'Hara searching through the bodies at the depot in Gone With the Wind, or the swoop down a staircase into a close-up on the key in Ingrid Bergman's hand in Notorious - still got through. But when Fraker says, "If you look at the great, great films, there's very little camera movement," it's the 1930s and '40s he's talking about. Page

1

|

||