KILL BILL • page 2 • page 3 • sidebar MOVE in MOVIE • page 2 • page 3 DVD • page 2 • page 3 |

|

Page

3

|

||

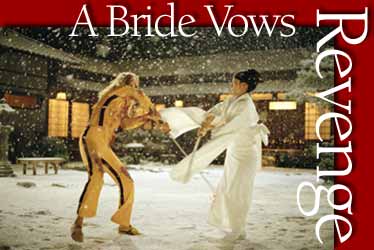

Eventually, though, the crew found its groove. Dolly grip David Merrill made sets of bilingual flash cards ("If we couldn't pronounce it, we could always point to it," says Ault); meanwhile, Kincaid says he and the Chinese gaffer, nicknamed G-San, "taught each other different versions of lighting - and Ping-Pong." The shoot's first sequence - known as "Crazy 88," for the number of Yakuza thugs The Bride kills - turned out to be one of the crew's most challenging. Four years after surviving Bill's wedding-day whack attempt, The Bride tracks one of her old teammates (played by Lucy Liu) to a Japanese nightclub called The House of Blue Leaves. Co-production designer Yohei Taneda recreated the Tokyo hotspot plank for plank so that any element - tables, ramps, silkscreen walls and even a bandstand - could be "Hollywooded" in or out depending upon the filmmakers' needs. Tarantino devised a complicated traveling shot to initiate the carnage. Starting behind the bandstand, as an all-girl Japanese combo bobs their beehives to a retro beat, Steadicam operator Larry McConkey walks the camera screen right, passing under an exposed stairway, which reveals The Bride descending into frame. The camera swings out from beneath the stairway and follows The Bride as she strides across the room down a side hallway. As she passes into silhouette behind a rice-paper screen, the camera rises and continues to follow from an overhead angle, descending again as she enters the bathroom; the camera then swings to find the House of Blue Leave's owner and her manager, and the camera leads them back down the hallway onto the main floor, where they ascend a staircase. The camera steps atop a crane and sweeps across the dance floor, past the band, to the opposite staircase, where it cranes in and booms down to reveal Sophie Fatale (Julie Dreyfus), a former member of Bill's assassin group and soon-to-be victim of The Bride. The camera then follows Sophie into the bathroom, and as she steps up the mirror, the camera continues past her to the wall of a stall. A scrim wall lighting cue reveals The Bride inside, waiting. Richardson and his crew spent just six hours rehearsing the shot and completed it in one day. "It sounds simple, but it wasn't," says Ault. "We needed to see the entire set at the beginning of the shot, so the crane Larry eventually stepped onto couldn't be there. We had people assigned specific duties to fly ramps in, roll the crane down, move walls out and back. We had to get the crane in while the camera was off doing the other part of the shot. "We needed a rig for Larry that would elevate him, travel about 20 feet and then descend so he could step off. We ended up using a motorized flying-chair rig that I designed and operated. It acted kind of like a carnival ride for Larry as he watched Uma travel down the hallway from above. Meanwhile, the wall [on the main stage floor] was opened up, the ramps were flown in and the Pegasus crane was prepared for Larry to come back out to." The highly portable Pegasus - whose arm allows 360-degree movement and can be built to several different lengths - is one of Richardson's favorite tools, and Ault carried one throughout the shoot. "Bob is happiest when he's up on the crane, wrapped around the camera," Ault remarks. "I think he likes it because when you swing an arm, it's so fluid; you don't have to worry about bumps in [dolly] track, and you can gently change elevations. Plus, the longer the arm, the less arc you have in your swing, and it starts to look just like a dolly move. John Toll [ASC] moved an Akela crane over blowing grass magnificently to get that kind of effect in The Thin Red Line." Ault also describes doing "some fun stuff" with a linear track rig. During one of her many throwdowns, The Bride effortlessly dodges a flying hatchet as it spins through the air, inches away from her nose. Normally such a feat would be created in post with special effects, but given Tarantino's aversion to all things digital, Ault felt compelled to summon some low-tech inspiration. "Quentin's a pretty organic guy, but obviously, we weren't going to throw hatchets at Uma," he quips. "To get the shot, we mounted the camera on a linear track, which is a little trolley on twin stainless-steel rods that the grips would push as fast as they could go, about 10 mph. It's a castered system, so no matter how fast you move it, you don't have to worry about it coming off. We put a bungee braking system on it, rigged the hatchet in front of the lens and ran it right past Uma's face. Quentin loved it when we came up with solutions like that." Ault also used the track to create a shot in which a wire-aided Thurman runs up a stairway banister. "To get the necessary speed, it had to be filmed with a camera that wasn't 'operated,'" he explains. "It's pretty much a locked-in shot, so we set the linear track up on the same angle as the banister, with pulleys rigged on it so we could move it as fast as a person at a run." Richardson's lighting for the sequence is as stylized as the camera movement, mixing scores of practical fixtures - Kincaid rigged more than 300 for the 140'x80' set - with brash transitions between soft and hard sources. "In this particularly long sequence, the lighting starts soft and moves progressively toward higher contrast levels," explains Richardson. "As the threat develops and the battling becomes more involved, the style of lighting alters to reflect the graphic nature of the action. The backgrounds drop off and the center arena becomes more prevalent." The cinematographer also employed his much-imitated "halo" effect "here and there," though he prickles at the notion of being pigeonholed. "I've actually done two films in a row now with very little use of that style," he says, referring to the Academy- and ASC Award-nominated Snow Falling On Cedars and The Four Feathers (see AC Oct. '02). Still, he maintains that his lighting for Kill Bill "is brutal when it needs to be." Another distinctive technique Richardson has been honing for several years is what he calls a "psychological" use of dimming cues within shots: "It might be in the slow fading-down of a background, or cross-fading between two different colors. I did this in a scene early in Bringing Out the Dead: Nicolas Cage is reviving the old man in his apartment, and the background shifts down about two stops towards black. It's extremely subtle. You won't consciously notice it, and if you do, then I've made errors. I've been doing this sort of thing for several years and I've become progressively better at finessing it. "In Kill Bill, we didn't do much motivated lighting in the classic sense," he adds. "I was more often trying to emphasize a psychological moment in the action. There's one cue where Uma is about to take on a gang of the Crazy 88 in a samurai battle. The foreground on one stage fades, the colors go through a lighting change, and we reveal a much larger stage where the battle continues in silhouette." The strategy also came in handy for lighting the film's elaborate moving compositions, which Tarantino preferred to shoot in sequence. Kincaid presided over 400 dimming channels and used "a very small remote board that I'd handhold while hiding behind the camera" as it zoomed around the katana-wielding characters. "When you're walking the camera around people," he explains, "a backlight will never work as frontlight because it's usually too steep. You have to dim that down and bring up a different front- and backlight for each new camera position." Richardson points out that every dimming cue means a corresponding shift in color temperature. "It's virtually impossible to get around," he says. "You can attempt to hide it with certain elements passing through foreground or background, or by passing another light through the frame itself. There are thousands of ways to do it, but it's actually a far easier task in black-and-white." Dimmer boards helped Richardson support Tarantino's desire to shoot in sequence, but some of the director's other predilections, such as his fondness for the Hong Kong-style snap zoom, required much more "assimilation" from the cinematographer. "I am not a fan of the zoom," Richardson says flatly. "It was entertaining for Quentin to have to break me in. He'd say, 'I got your virginity on this, Bob, and if it hurts, you know what? You're going to have to learn to enjoy it.'" Luckily, it didn't take Richardson long to loosen up. "There was a certain point in the shoot where it just felt great!" he acknowledges with a chuckle. "After that I'd start thinking, 'Hey, let's just toss in a snap here, a snap there ....' Sometimes Quentin would come up with a smile on his face and say, 'Not the right time for it, Bob, but I'm damn glad you're doing it.'"

Page 3 | ||