HERO • page 2 • page 3 • sidebar GOLDEN YEARS • page 2 • page 3 DVD • page 2 • page 3 |

|

Page

3

|

||

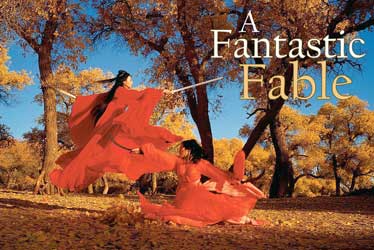

In the Trees In Hero, all the actors are either up a tree or under a lot of water. They spend half of the forest sequence upside-down, heads bulging with blood, hanging painfully from a crane that will drop them into the shot. Pained and cold and aching, they're acting and fighting like the great actors they are all the same. Calligrapher Broken Sword (Tony) is undistracted from his writing, trying to express the Qi of the fight and his character in one. He writes on, regardless of the arrows showering down around him. In this scene, his calligraphy brush is his sword and his writing is his Kung Fu. Focus is what it's all about. When his brush is broken (by an arrow), he's to snatch one arrow from the air and carry on writing without missing a beat. In most of the team's experience, a stunt like this will take hours. We rehearse and finesse, and in practice Tony can't catch the arrow. But then he says he has found his rhythm. Dinner has arrived but we decide to shoot. Tony gets it on the first take! Library The white of our sets makes them look like something out of an Ikea catalogue. Those who build our sets and finesse the spaces see my work as separate and unrelated to theirs. Just a little dirt would make such a difference. The way things look, my light has to cover up more than it reveals. In my (Hong Kong-based) world, I'd be at these walls and pillars with a couple of spray cans right away. But that isn't done here. I guess the dictum "Each to his needs and abilities" really means, "You dig your own hole. Stay out of mine." System Management There are no grips in this world. The Steadicam operator takes care of the cranes and scaffolds; the sound man gets bored and operates the wind machine. The assistant directors are off mustering the horses, and my gaffer is on a fresh-vegetables search for our next meal. Brett and Jasmine, my Australian assistants, are having trouble accepting the way things are done here. They're frustrated by the crew's indiscriminate borrowing of filters and lenses and other pieces of equipment that they've spent a month organizing. We're only halfway through the first day, and already things are misplaced or unfound. "It's in the truck" isn't what they want to hear when I'm asking for a piece of equipment here and now. It isn't really a lack of understanding or a mark of disrespect. "It's just like Chinese food," I pontificate. "Why have separate plates when we can all eat better from the same bowl?" Jiu Zhai Gou The road to Jiu Zhai Gou is boulder-blocked and meandering, 600 kilometers and at least 10 hours in the best weather to the Southwest from Chendu. "Who would want to bother just for a couple of lakes?" I ask no one in particular. At least three voices reply, "You haven't seen them yet!" Ping-Pong "How do they fight on the lake without breaking the surface I want so much?" Zhang asks. I'm thinking, "Where the f**k can the cameras go?" "Think Ping-Pong on water," smiles martial-arts director Chen Xiao Dong, enigmatic as always. "It's very Oriental," quips producer Bill Kong, "if we can make it work." Zhang is excited by the idea of the world in a drop of water, the cosmos in all small things. Chen extrapolates: "We start wide with the full majesty of the lake and the implications of their encounter, then the thrust and parry of the fight concentrates our focus." Zhang: "And their Qi." Chen: "We stay tight, all faces and swords and drops of water." Zhang: "Holding focus will be a bitch, Chris." Me: "I can't even work out where the cameras will be!" The day is colder than we expected, and rain lightly disturbs the mirror flatness of the lakes. When we scouted and decided to shoot here, the lake was calm, transparent and turquoise-blue, reflecting the green pines rising 2,000 or more meters straight up. Three cranes suspend Jet and Tony way out over the lake. As they fly back and forth, their swords only tip the water to rebound them into the fight. They're such masters that they don't even ripple the lake. The problem is the World Heritage stuff: we can't unbalance the delicate landscape, one of the few remaining natural panda habitats. You can't even throw a rock into this glacial, mineral ecosystem. How to put a pagoda in the middle of the lake and have actors fly in and out? "Discreetly" is the word of the day. We will shoot lots in high speed. We only shoot wide when the lake is flat and undisturbed. Strength in action that shows no effort, energy from the water that is not broken at all. Now it's time to get wet - and cold. Winter approaches, like the clouds every other day, like the wind around 9:30 a.m., like the paparazzi. At 3,000-plus meters up, the shoot is difficult enough as it is. We have few axes to shoot from. The access is narrow and the cranes that our actors fly by take up most of the space. The wood of the walkway we shoot from is frosty or slippery with water most of the day. We're very much frontal - no great angles, just the water backed by green in yellow mountains capped by blue sky. The poetry of the landscape and action are going to make or break each day. We're restricted to parallel action because the only space we can shoot from is totally parallel to the lake. Solution: shoot on land, and through a very simple pool of water that gives the sense that we are under it all. We move to flat land close to the main parking lot. What we gain in access and angles we lose in crowd noise and intrusive visitors. Mountains in Black-and-White We chose this location, Dang Jin Shan, for its topographical diversity: slate and shale outcrops and some kind of black/white fault that dominates the vast plateau where we'll shoot our scenes. But the plateau only works visually for a short part of each day, so we turn away from the main reason we came here and shoot towards the north of the plateau. We're shooting so much into the light that the mountains on that side read mostly as black. Yesterday's sun is now overcast. Wind rising. Rain on and off. Tired troops and nowhere to go. "Can we shoot?" asks assistant Brett. "We have no choice," is my sorry reply. Zhang used to be a cameraman. It doesn't show when he says, "Don't worry about continuity." Brett is shocked at Zhang's guts. "It looks like midnight instead of half past three." "The audience won't notice," Zhang claims. "The story is the point. The content is the only thing that has to match." Practice The practice of art and the practice of meditation or cooking are the same: you have to repeat and repeat. The basic moves and procedures create a familiarity that frees you enough to open you to creative possibilities. The ritual of the act makes thought and movement one. You have to let go to find the essence of things. "First there is a mountain. Then there is no mountain. Then there is." It's Buddhist, it's a Sixties song, and it has been appropriated by New Age mystics, MBA charlatans, teenage surfskiers, and now me. To me it means: 1) Effort is focused. We prepare a film till we feel confident. We haven't started yet. 2) The team is finding its rhythm. Could be second day of shooting, or never - in which case there will be no "then there is." Our action and the acting become responsive or intuitive. We're one with the moment or content at hand. We think we have a film. 3) "It just fell off the truck ... so we used it." What we do and how we approach things are nothing more or less than the light or the location or the words, or the film itself. Art is what artists make; good imagery is a lifetime practice, not a technical ability or something appropriated for the film of the day. What we made is yours now.

Page 3 | ||