HERO • page 2 • page 3 |

|

| Golden

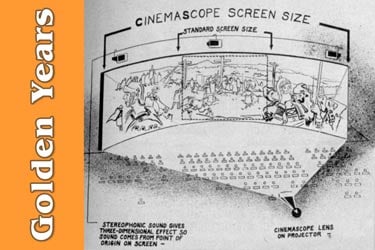

Years 20th Century Fox introduced CinemaScope 50 years ago with The Robe. Shortly thereafter, Panavision was born. |

||

Photos courtesy of the ASC Archives, David Samuelson, Panavision and Kevin Brownlow. The Panavision company was formed in 1954 to manufacture, supply and distribute anamorphic attachment lenses to the movie theaters across America that did not wish to purchase such lenses from 20th Century Fox. This came about because, with the introduction of CinemaScope earlier that year, there was an enormous need for projection lenses that Fox could not immediately satisfy. Initially, the studio only made the lenses available to theaters that would also agree to install four-track stereo sound systems at the same time. The principle of "anamorphic" imagery - a distorted image that looks normal when restored - goes back to the 16th century. Originally, this process was accomplished by means of drawings or paintings to be viewed (usually) with the aid of a cylinder-shaped mirror. The first patents for anamorphic lenses were granted in the late 19th century. CinemaScope was derived from an anamorphic-lens system created in 1927 by French optical designer Dr. Henri Chretian. It is said that having seen Abel Gance's great picture Napoleon, which was filmed with a combination of three cameras and projected by three projectors onto three side-by-side screens, Chretian remarked that he could achieve the same result with a single camera and projector, using the optical principle he had developed for tank periscopes during World War I, then only a few years previous. He called his system "Hypergonar" and manufactured a small number of attachment lenses that could be used either in front of a camera lens or for projection. Many of these lenses were destroyed during World War II when Chretian's laboratory was bombed. During the late 1940s, when all of the major Hollywood studios realized that television would make deep inroads into their market, they scrambled for a means to make the cinema experience more spectacular than the format that could be achieved by a television set. The answer was "the big screen." Cinerama (1952), which utilized three projectors, a deeply curved screen and four-track stereo sound, was the first to come and go. Todd-AO used obsolescent Mitchell BFC 65mm film cameras, to which an additional 5mm was added at the print stage to accommodate stereo sound tracks. If nothing else, the format, which was moderately successful for a time, showed that a widescreen aspect ratio with high-quality images - which television could not emulate - was the way to go. Paramount took an option on the French Hypergonar anamorphic system but allowed it to lapse after deciding to proceed with VistaVision, a widescreen system that used an 8-perf-wide 35mm picture, with the film traveling horizonally. Warner Bros. had anamorphic lenses manufactured by Zeiss (one of the original patentees in the 1890s) and called the system Warner SuperScope. At the same time, 20th Century Fox took a serious look at reviving the widescreen Grandeur system it had developed and promoted in 1929-30, but concluded it would not be economically viable. The studio then began examining alternative widescreen systems. When Fox heard that Paramount had dropped its option on Chretian's Hypergonar anamorphic system, a group of senior Fox executives, including Spyros Skouras and Earl Sponable, the studio's technical director, flew to Paris to take a closer look at it. What they saw impressed them, and at the end of 1952 they decided to go with the French system. They called it CinemaScope and decided the format would make its debut with the epic The Robe, which was already six weeks into production. (See Wrap Shot, page 112.) Subsequently, the show's sets had to be torn down and rebuilt at twice their original width. Fox used the best of the three anamorphic attachment lenses they received from Chretian on The Robe. (The other two were used on How to Marry a Millionaire and Beneath the 12 Mile Reef.) Each film was shot with a single anamorphic attachment and a single 50mm backing lens. This meant that no wide-angle or longer focal-length lenses were available. The lenses were considered so valuable that each had its own bodyguard. Page

1

|

||