HERO • page 2 • page 3 |

|

page

3 |

||

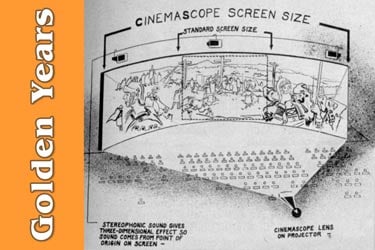

Gottschalk and Wallin incorporated such devices into their anamorphic lenses and linked them to the focus ring, so that as the distance and focus setting were changed, the prisms would rotate, adjusting the degree of anamorphic squeeze to suit the focus distance. It is said that when Gottschalk first demonstrated his anamorphic lenses at a special screening for senior MGM executives, the entire audience stood and applauded at the end of the screening. Gottschalk patented this device and kept it secret for as long as the patents lasted. There were many others from all over the world who aspired to manufacture anamorphic lenses, most of them using a fairly simple cylindrical lens made by a small manufacturer in Japan. Put behind an off-the-shelf 10:1 zoom lens, they didn't look too bad - it was probably the failings of the zoom lens that hid the shortcomings of the rear anamorphoser. Put behind a good prime lens, they weren't too good. Few attempted to design and manufacture a fixed-focal-length lens with a cylindrical front anamorphic element. It was the battle between Fox and Panavision for the domination of the anamorphic-lens market that was the most bitter and hard fought. Fox became very upset when Panavision took out full-page advertisements in the leading trade papers showing a fat-faced actress photographed, it said, with an "ordinary" anamorphic lens, next to a glamorous picture of the same actress that was "photographed with a Panavision anamorphic lens." Panavision engineers also gave hard and gritty lectures and demonstrations at the ASC and at SMPTE (Society of Motion Picture and Television Engineers) conferences. On more than one occasion, senior Fox executives wrote to the SMPTE and ASC presidents to complain that Gottschalk "and MGM had been allowed to use [your] forum to spread damaging propaganda about CinemaScope." They noted that it was "unfair to show comparisons of the lenses at close range because that was not the way CinemaScope lenses were used." In a letter to the president of the SMPTE, Sol Halperin, ASC, head of the camera department at Fox, wrote that CinemaScope lenses had "not been designed to photograph anything at a distance closer than seven feet [2.1 meters]." Actually, it seems as though Fox foresaw that there would be a problem with close-ups, because in an article published in the March 1953 issue of American Cinematographer, while The Robe was still in production, it was noted: "Although close-ups are reproduced dramatically... few may be needed because medium shots of actors in groups of three or four show faces so clearly...." An accompanying illustration showed such a setup. Eventually, Panavision won out, and the day came when Fox ordered Panavision anamorphic lenses for a Fox production. It is an interesting fact that very many years later, after Gottschalk had died, one of the senior Bausch & Lomb lens designers came to work at Panavision and was mortified to discover that some of the "superior" Panavision anamorphic lenses that had caused his previous employer so much grief were, in fact, Bausch & Lomb originals that had been remounted, rebarreled and modified with the addition of Gottschalk's secret astigmatic attachment - and no one at Bausch & Lomb knew! In hindsight, Fox's introduction of Cinema-Scope proved to be every bit as momentous as the introduction of sound, and the cinema has benefitted from the continued development and perfection of an imperfect original invention. The fidelity of the sound in The Jazz Singer (1927) is a long way from the sound we experience in the cinema today, and so it is with anamorphic lenses. Chretian, Skouras, Sponable and Gottschalk would not believe the image quality we see on our screens today. In 1964, Samuelson Film Service Ltd., owned by the author and his brothers, became Panavision's sole overseas representative. Among the early Panavision productions serviced by the London company were Oliver!, Fiddler on the Roof, Star Wars and Superman. The author would like to thank Stephen Huntley for information culled from Earl Sponable's collected personal documents on deposit in the Rare Book and Manuscript library of Columbia University, New York, and published in the Film History Journal of September 1993. Thanks also to Kevin Brownlow and Photoplay for the Napoleon pictures. page

3

|

||