President’s Desk: An Artist, a Murderer and a Cinematographer

It can be said that Eadward Muybridge’s first experiment with instantaneous photography was the point at which cinematography was born.

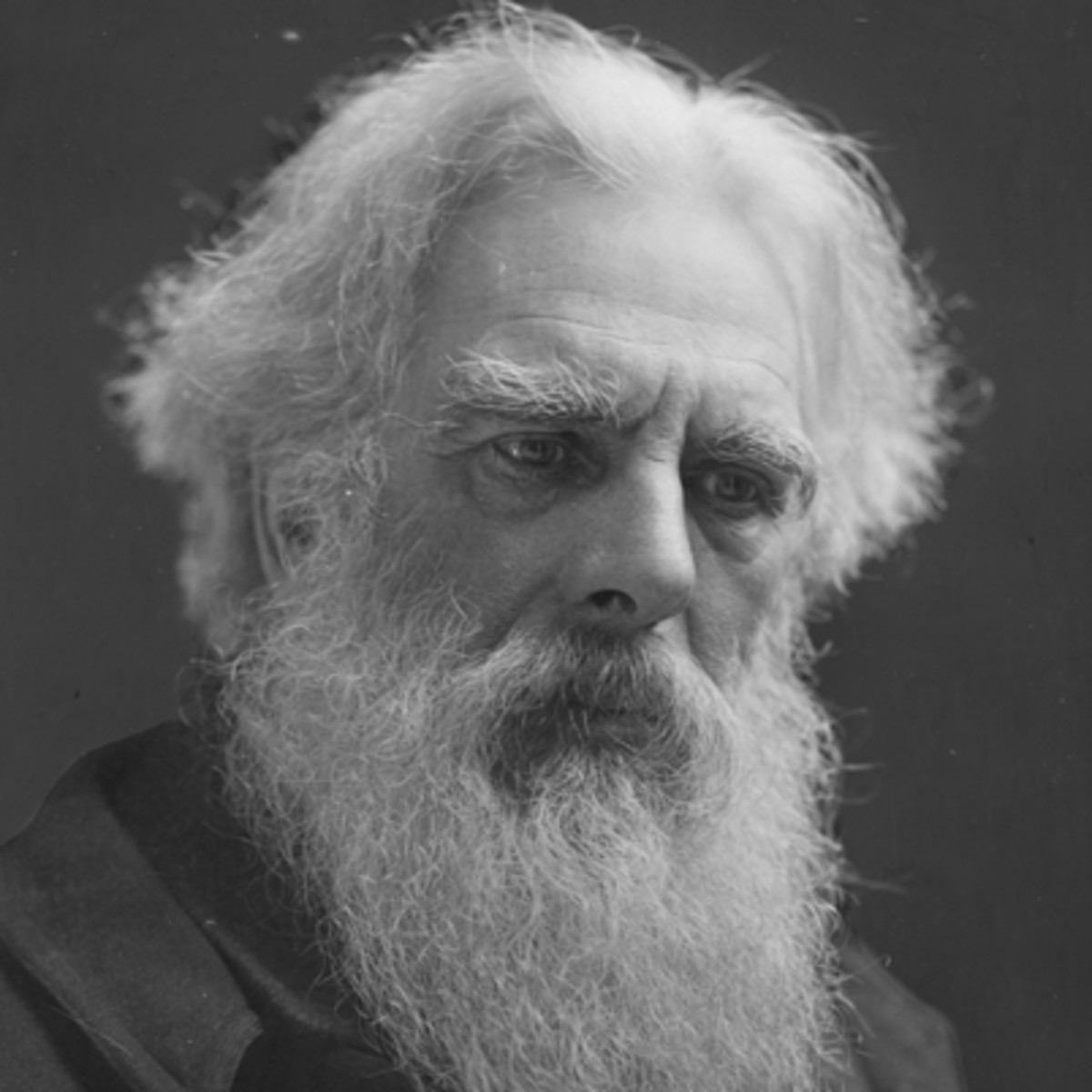

A pioneer of visual studies of animal and human locomotion, Eadweard Muybridge was recognized and celebrated in his field to such an extent that at one point it might have saved him from the hangman’s noose. In what was tried in court as a crime of passion, he shot and killed his wife’s lover with his Smith & Wesson revolver. But his extraordinary importance to science surely contributed to the jury’s decision to set him free. He went on to produce countless more “locomotion” photographs, including striking studies of the human body in motion.

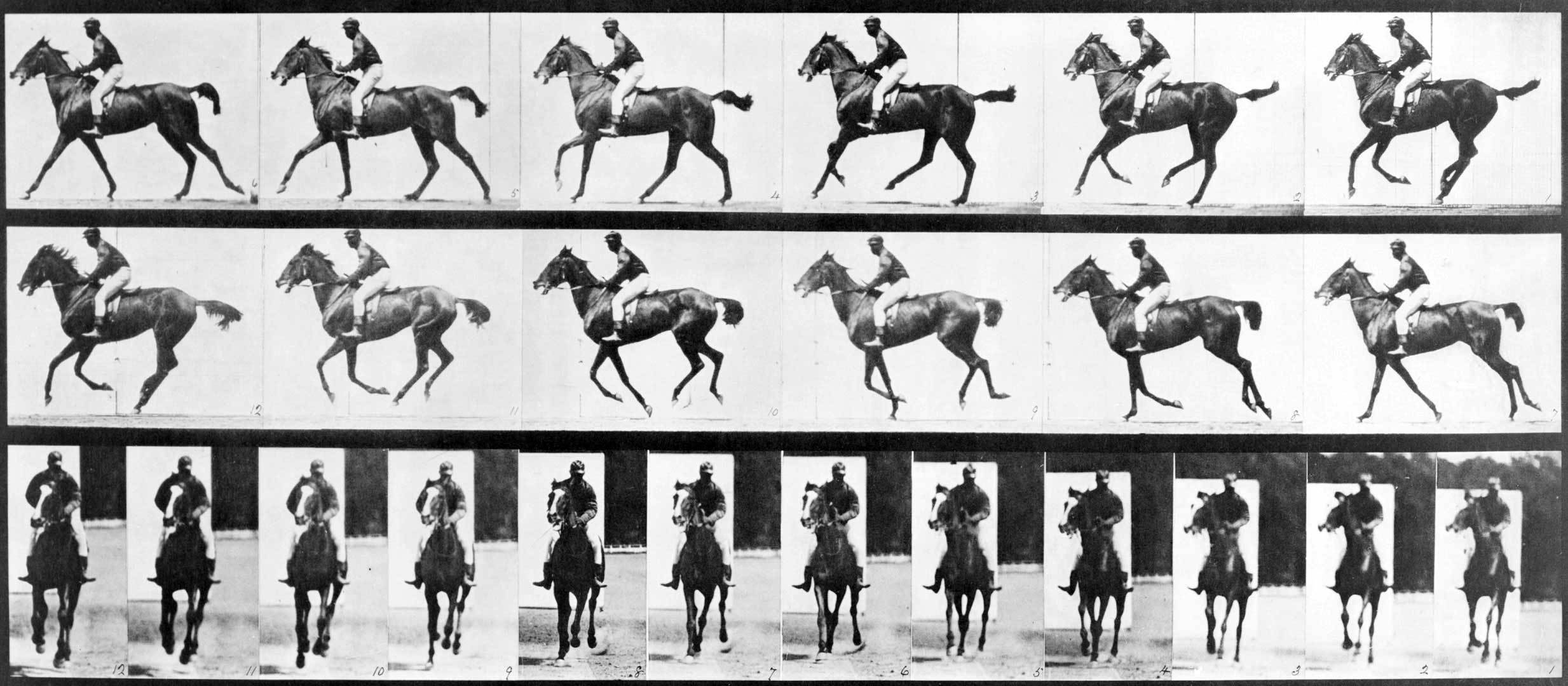

Born in England in 1830, Muybridge first pushed the boundaries of technology when he was tasked by businessman and former California Governor Leland Stanford with photographing the quick movement of a horse. At the time, there was an intense debate among racing aficionados as to whether, at some point, all four hooves of a galloping horse are off the ground.

So Muybridge set out to take a series of instantaneous photographs at a racecourse in Sacramento, Calif., of a racehorse named Occident. The experiment proved that there is indeed a moment at which all four of a galloping horse’s hooves are in the air.

From a technical point of view, capturing these photographs was no easy task. At the time, wet-plate photography needed exposures of up to 30 minutes. Muybridge thought over the matter and skillfully applied his knowledge of chemistry, and then used Dallmeyer wide-angle optics to take an instant picture — and succeeded in getting the first shadowy and indistinct picture of Occident at a trot.

This was by no means a picture with gray tones and subtlety. To get the necessary exposure, Muybridge erected a white wall that was lit by the sun, and he then photographed the horse in silhouette. He spent years refining the process, and along the way devised a means of triggering multiple cameras, 12 to 25 in a line, with a brief interval in between them and a shutter speed of 1⁄1000 of a second.

It can be said that this was the point at which cinematography was born.

Muybridge continued his scientific work, recording the motion of animals and, in the later years of his experiments, concentrating more and more on humans. The result was a visual dictionary of moving human figures, a study of movement in everyday life. Eventually, Muybridge’s delight in narrative images took over his scientific work, and he started to consider himself more an artist and storyteller. There are his studies of a female model wearing a fluttering shawl, a mother spanking her child, a kangaroo hopping in a genteel manner and a mule named Denver taking a seat in a chair. And what laws of physiology could he have possibly been trying to illustrate by photographing a woman throwing herself into a haystack?

When artists began studying these images in detail, the results were remarkable. His visuals became a source of inspiration for painters like Marcel Duchamp, who drew inspiration from Muybridge’s motif for his iconic modernist painting Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2.

His later work exudes aesthetics and style, as was evident in his development of the zoopraxiscope, which allowed for the display of moving images. For the Chicago World’s Fair in 1893, he put together a series of projection materials, more colorful and more detailed than ever before, and showed them in the Zoopraxigraphical Hall, which is now considered to have been the first commercial movie theater. Nearby, however, German competitor Ottomar Anschütz demonstrated his electrotachyscope; also known as the “Electrical Wonder,” this was essentially a spinning-disc peep-show machine that, perhaps most importantly, could be watched for a nickel.

Shortly after that, in 1895, the Lumière brothers held the first screenings of their films in Paris. Muybridge realized he could no longer compete. His life’s work no longer seemed as miraculous, nor was it a commercially viable source of entertainment. But it was Eadward Muybridge who not only first made possible the analysis of movement using sequential photography, but who imbued his work with an elegance and style that can be considered the beginning of cinematography.

Kees van Oostrum

ASC President