President’s Desk: Resolution Resolved!

“You can’t depend on your eyes when your imagination is out of focus.”

I woke up one-morning last month with a scare, afraid that something was wrong with my vision. Several times I had been to 4K screenings of various projects and tests, and more than once I had walked away having not been able to see or experience what the presenters were talking about. All the detail, the enhanced color and contrast — it went right by me. I nodded “yes” and agreed because there was really no point of reference. When someone comes at you with mathematical equations about spatial resolution and constantly increasing K values, what are you going to say? I suppose it’s all a great advancement of technology. But when I woke up that morning, I figured, just to be safe, I’d best pay a visit to my optometrist.

Dr. Kim is on Larchmont, about a 30-minute walk from my house, and while I was making my way there, a billboard caught my eye: a beautiful sunset scene, representative of the human condition, shot in 4K on an iPhone! I was enamored with the picture’s beauty — but I was also convinced that my stroll to the eye doctor’s was most timely. In focus, the billboard was not.

Once I arrived at the optometrist’s office, Dr. Kim set about the business of focus immediately. The manual refractor head, of German origin, was swung in front of my face; in rapid succession, the lenses flicked from weak to strong while I discerned black letters of various sizes against a white field. All went well save for the littlest ones on the bottom of the page. No matter what combination of glass the doctor tried, I could not clearly make them out. It wasn’t so much that they were out of focus, though; it seemed that their appearance would spontaneously and unpredictably change.

Dr. Kim swung the manual refractor away and said, “There is nothing wrong with you. You have 20/20 vision.”

“But what about the very little letters?” I asked. “I wasn’t able to identify them.”

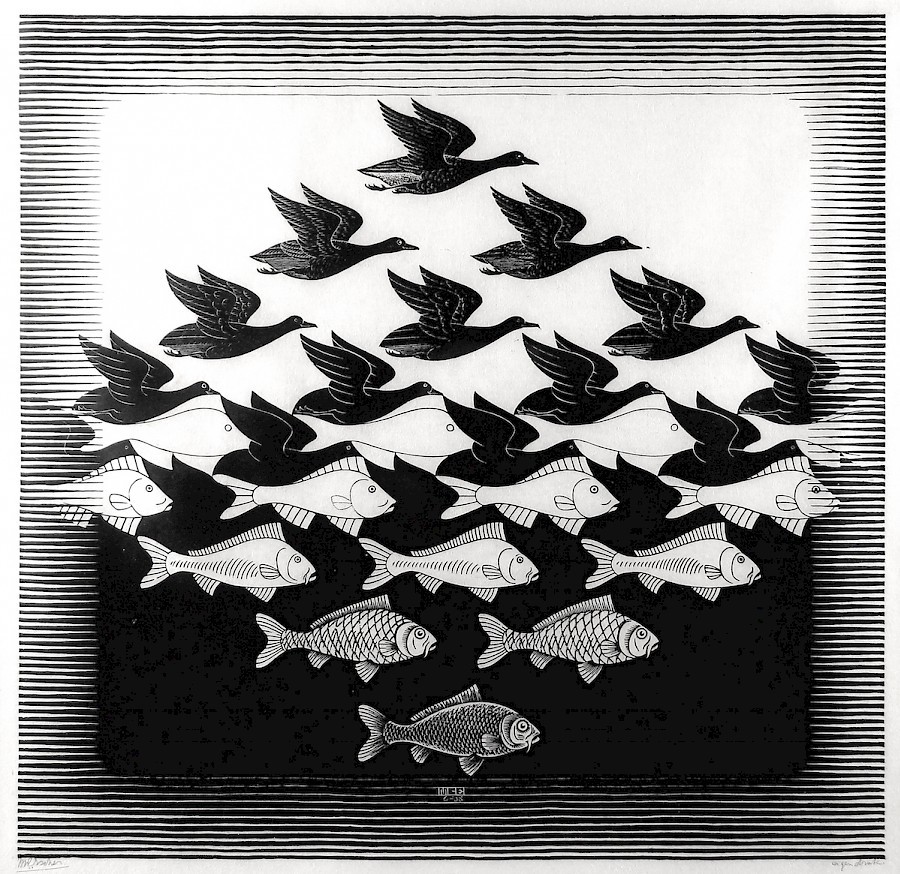

“That has to do with illusion, the brain’s interpretation,” Dr. Kim explained. “It’s like when you look at an M.C. Escher image: One moment you think you see a fish, and the next moment you think you see a bird. It has to do with how you condition your brain, what you intend or want to see — sometimes what you are told to see!”

I left the office utterly confused. As I walked, the streets seemed to turn into Escher’s staircase. I walked up and found myself walking down. Thinking it must be time for a medicinal drink, I struggled over to the bar at La Poubelle on Franklin.

At the end of the bar, shrouded in darkness, I found my friend Steve Yedlin, ASC hunched over his laptop.

After I’d told him my tale, he showed me identical images originated in a variety of Ks, with no perceptual difference. He whisked through equations and blew up digital photo frames, convincing me that my brain had not been so wrong after all — and neither had my eyes! As the mojito further relaxed my anxieties, Steve explained that corporate hype and misguided tests had led many a cinematographer to accept the notion that more Ks made for a better image. Like a “Last Jedi” of resolution, Steve passionately and eloquently rebuked these specious claims, wielding his laptop like a lightsaber in the dim light of this iconic Hollywood “cantina.”

The sun was setting as I made my way home, and again I walked past the iPhone billboard. Its photographed sunset now blended with the magic-hour sky; it looked spectacular, although it was not as sharp as the real world. But who cares? It’s a unique enough experience just to see an image blend so artfully with nature. At the very least, it convinced me I had the right phone in my pocket.

I don’t know whether it was the mojito or Steve Yedlin that helped me to again trust my eyesight. Or perhaps Dr. Kim allowed me to accept the world according to Escher. Either way, it all comes clear in Mark Twain’s quote: “You can’t depend on your eyes when your imagination is out of focus.”

Kees van Oostrum

ASC President