President’s Desk: The Waving, Bobbing Camera

What the New Wave taught us — and what the bobbing camera reminds us — is that we should not be slaves to the medium.

Floating, waving, rolling, listing. Messy, off-kilter, unexpected, unpredictable. Loose head. “Breaking it up.”

These are some of the terms and phrases that are frequently thrown at cinematographers when discussing styles of camera handling and framing, resulting over the last couple of years in a somewhat novel approach to operating that was new to our stylebook. Or was it? I am a firm believer that nothing is really new; it’s human nature to experiment all the time, and through our experiments, we continually rediscover what was previously known. Trends unintentionally grow out of an unstoppable desire to be different, to tell a story another way.

Considering this purportedly “new” loose camera style, I went back to look at the films of the French New Wave, known in its native tongue as the Nouvelle Vague. In my opinion, the style that grew out of the New Wave films is one of the most influential in the history of filmmaking.

In the late 1950s, a small group of critics writing for the French film journal Cahiers du Cinéma began making their own movies as a protest against the traditional, impersonal style that had become endemic to French cinema. Their ideas can be traced to Alexandre Astruc’s 1948 manifesto, “The Birth of a New Avant-Garde: La Camera-Stylo.” Astruc’s essay outlined several principles that were later interpreted by the Cahiers du Cinéma critics, including François Truffaut, Jean-Luc Godard and Claude Chabrol, who were among the New Wave’s most prominent members, directing films including Les Quatre Cents Coups, À Bout de Souffle and Le Beau Serge, respectively.

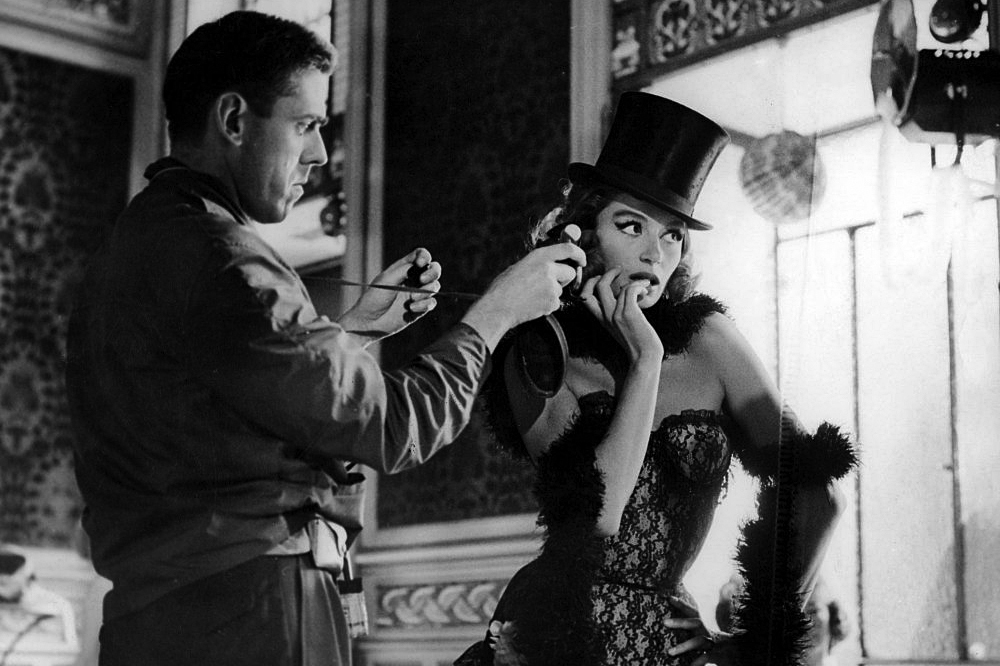

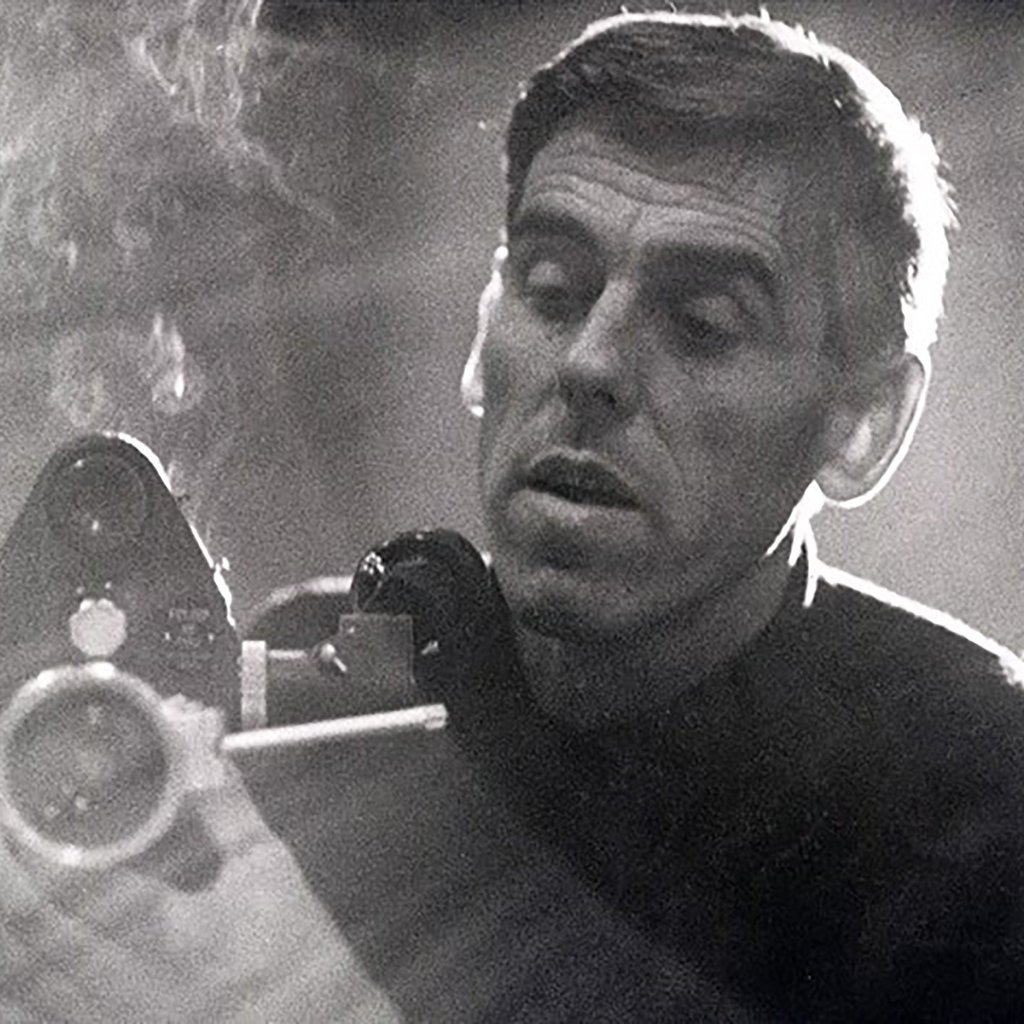

Henri Decaë was perhaps the most sought-after cameraman at the beginning of the New Wave, but Godard quickly introduced a cinematographer who, until then, had worked primarily as a war photographer and photojournalist. This was Raoul Coutard, who came to embody the cinematography style of the Nouvelle Vague. (He’s there at the top of this page, shouldering his Caméflex while Godard pushes the wheelchair as they line up on Jean Seberg and Jean-Paul Belmondo while shooting Breathless.)

His camerawork had its foundation in the reality of documentaries. Most of his work was handheld. He spoke of a camera in constant search for visual honesty — and yes, it floated, shook, moved impulsively, and generally did anything that was counter to the stylized “perfection” of the French film industry of the day, represented by top cinematographers including Henri Alekan (Anna Karenina) and Sacha Vierny (Last Year at Marienbad).

Coutard’s simplified lighting was initially driven by the lack of budget. His early films were mostly shot with available light; on some occasions, he would replace practical bulbs. Later, he began to bounce floodlights off of white or silver material placed on ceilings, creating a soft, even light for the room. Though it might have lacked sophistication, the lighting nevertheless was perfectly in sync with the principles of the New Wave. Indeed, the New Wave was not really defined by a set of rules, but by their absence. It was about breaking all the rules that were considered boring and restrictive.

Today’s bobbing camera and “shoot anything that moves” style similarly deconstructs cinematography to a bare essence. It’s perhaps as close as we’ll get to a second Nouvelle Vague — but, unfortunately, it’s not nearly as inventive or thought-provoking. What the New Wave taught us — and what the bobbing camera reminds us — is that we should not be slaves to the medium. You don’t have to shoot a certain scene in a certain way just because it’s considered “appropriate.” At the end of the day, only your vision matters.

Coutard passed away a little over a year ago. He worked as a cinematographer on more than 80 films, but it’s his work with the directors of the French New Wave that comprises his most lasting legacy. It was a time he recalled with fondness and a touch of amusement.

“At the beginning of the New Wave, they thought they could do anything because they had no idea what cinema was,” Coutard reflected in a 2010 interview with Post Script. “That’s what made it dramatic, that they didn’t think there were limits to what you could do. I put together a system to make it easy to work.”

Kees van Oostrum

ASC President