"The Look Is Part of the Joke": Shooting The Naked Gun

From bank heists to slow-motion brawls to unhinged snowmen, cinematographer Brandon Trost shares his dead-serious approach to the zany action-comedy.

MacGruber is a special movie to me. I credit that film — executive produced by The Naked Gun director Akiva Schaffer — with starting my career in shooting comedy. We wanted it to not look any different than the 1980s Don Simpson/Jerry Bruckheimer movies it references, and since then, I’ve made many comedies that are designed to not look like comedies. The look is part of the joke.

The Naked Gun is an evolution of that style.

Akiva and I very much wanted The Naked Gun to feel like an analog 1990s action movie. One of our biggest creative touchstones was the James Bond film Tomorrow Never Dies, shot by Robert Elswit, ASC. We also referenced many films by Tony Scott, specifically his work from the ’80s; Beverly Hills Cop II (Jeffrey L. Kimball, ASC) served as an especially strong influence. We went to great lengths to emulate the style of those films, using all of their different ingredients as part of our alchemy for creating that ’90s-action-movie tone — lots of long lenses, smoky interiors and wet downs at night.

Aiming for an Analog Feel

We knew from the outset that we wanted to shoot anamorphic. I chose Panavision E Series lenses because a lot of the movies The Naked Gun references were shot on them. They were the cream of the crop in the ’80s, and to this day I use them for other films, as well. We knew that we were going to shoot the movie digitally, on Arri’s Alexa LF, but we went to great lengths to give it an analog film-like tone. We also performed a filmout, using FotoKem’s Shift process, which is an analog intermediate. Kodak 2254 was developed, skip bleached and re-digitized for final tweaks, in collaboration with FotoKem colorist Dave Cole, and we shot with the filmout in mind. I shot the whole movie at 3,200 ISO, which is something I tend to do on many of my projects, simply because I like the way that a higher ISO bakes in a slightly noisier image.

Lighting the Bank Heist

For the opening bank-heist sequence, we were definitely pulling from films like The Dark Knight (shot by Wally Pfister, ASC) and Point Break (Donald Peterman, ASC). We wanted to first set the stage for the style of the movie, without any jokes… until this little girl shows up, who is revealed to be Lieutenant Frank Drebin Jr. (Liam Neeson) in disguise. I love that misdirect. We beamed shafts of light through windows into our smoky interior, and we wanted lots of camera moves, including crane work, for the scene. We wanted shots that we would’ve thought were rad even if this wasn’t a comedy.

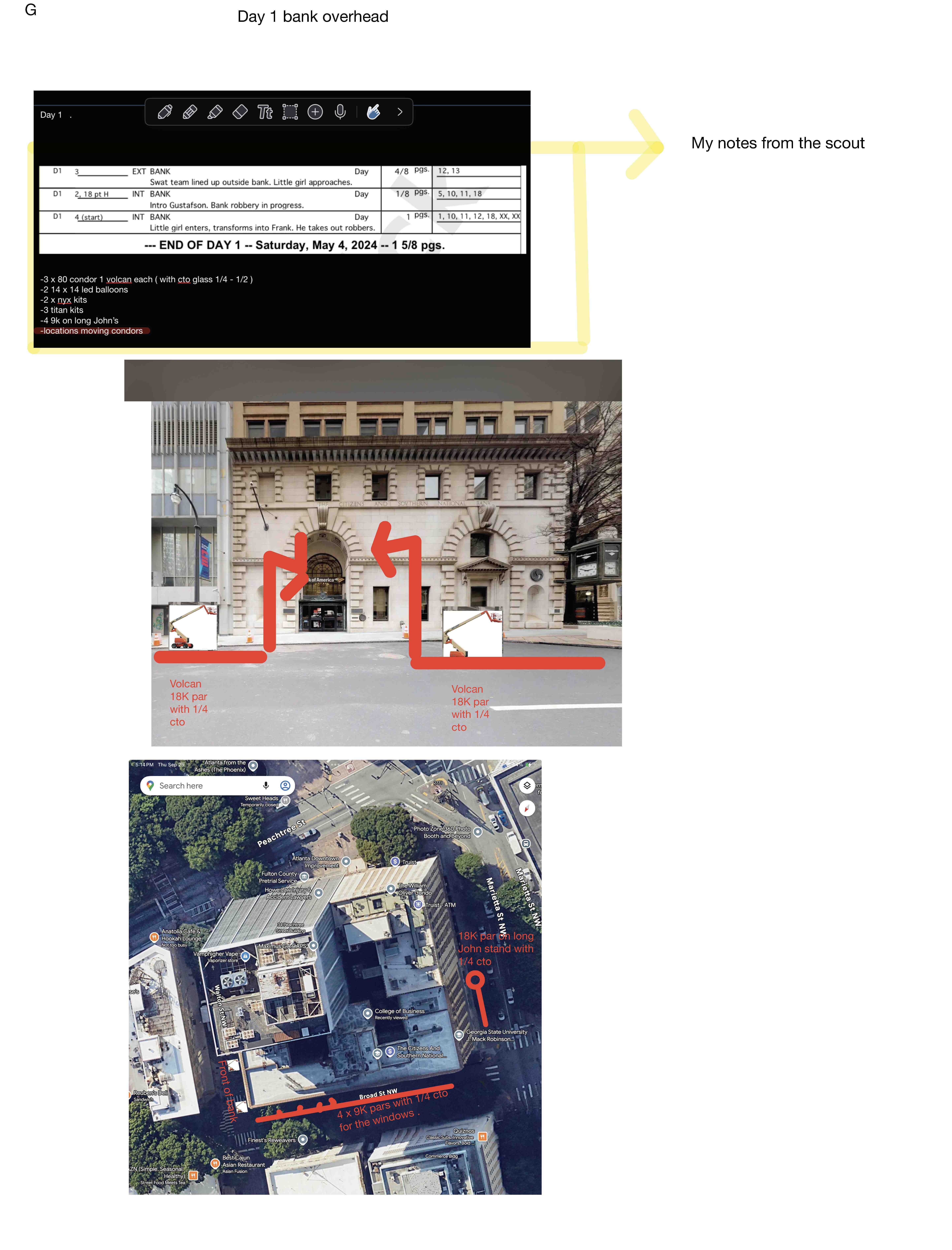

The one thing that I didn’t love about our location, which was a real working Bank of America in Downtown Atlanta, was that I wanted multiple shafts of light to enter the space, but the building didn’t have a lot of windows. (See my initial notes from the scout below.) There were only two main windows, with one on each end of the bank. For the primary window above the entrance, we had two Condors — each with an 18K Volcan. We created a crisscrossing of light beams, with one beam from the right side of the window and another from the left; this was a trick we relied upon to spread the beam in the smoke and make it look wider than what it would otherwise look like naturally, if only sunlight was shining through.

For the other large window on the opposite side of the bank, we could only push one 18K light through on a high stand for a glow, because it was difficult to access and we weren’t allowed to position lifts on the street outside there. For a couple of offices within the building, we pushed smaller HMIs through from the street outside; however, they weren’t used so much to light the scene inside, but more for incorporating background detail. The heavy lifting was really done by that main-entrance window, as well as an overhead 14'x14' LED balloon source, which gave us some soft, dim toplight. Our setup was simple for most of the sequence, and we didn’t really pull out anything else to light most of it — except for the very last shot, in which Frank has his leg raised up after successfully stopping the heist. For this moment, we pulled out a large frame and lit him nicely there with a diffused source.

A Serious Treatment for Silly Slow-Mo

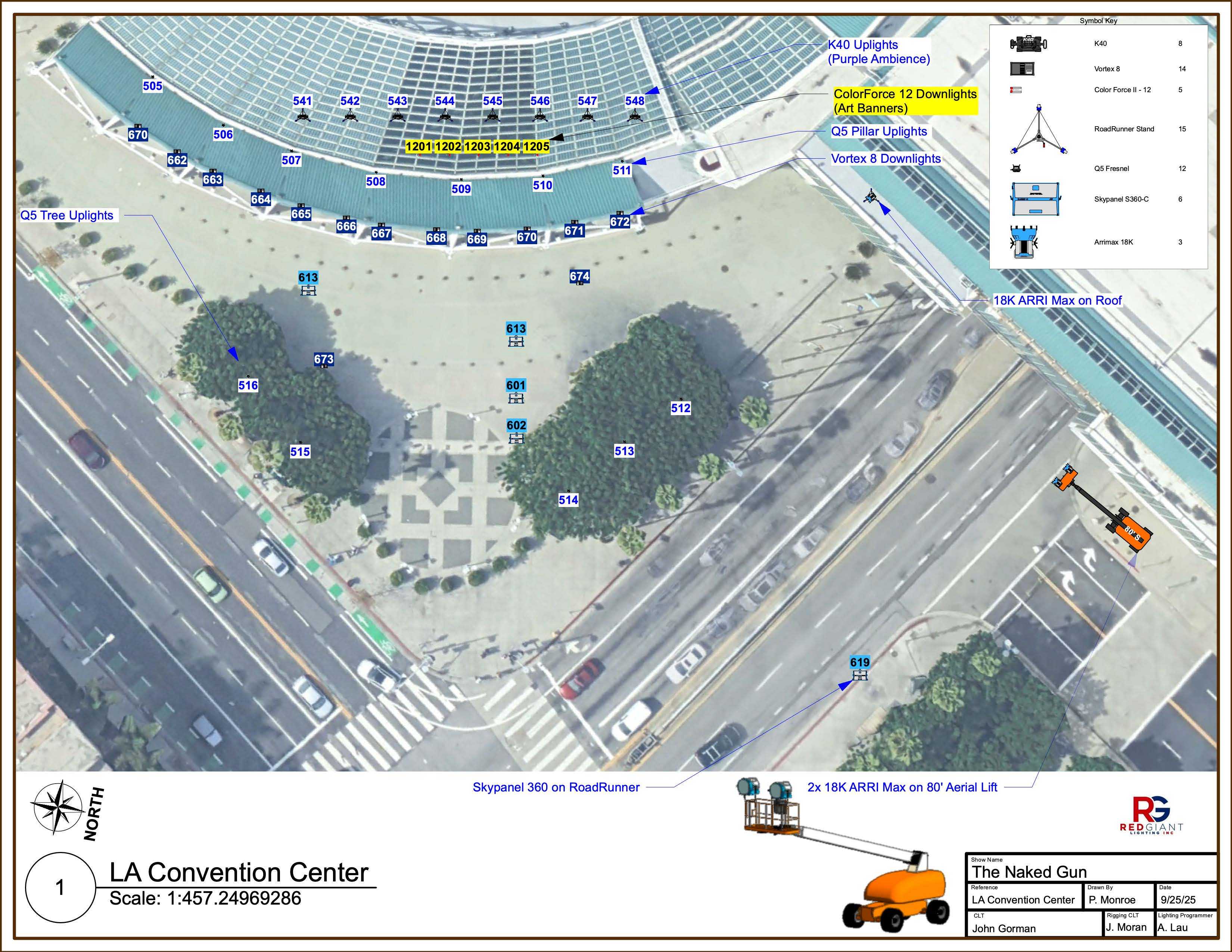

For one sequence toward the end of the film, we deviated from our vintage approach and leaned into a more modern John Wick-like style of action. The scene takes place outside of an arena, with Frank using his gun clips to basically ricochet off of bystanders' faces. The scene called for a lot of crazy slow-mo and dynamic camera moves. We shot this sequence in front of the Convention Center in downtown L.A. as part of additional photography months after we’d wrapped, working closely with our L.A.-unit stunt coordinator, Wayne Dalglish, who had previously designed amazing fight choreography and stunt sequences for James Gunn.

The scene was quite involved, and we really prepped the hell out of it, even though it doesn’t run for very long in the movie. For every shot in that sequence, one could look at our stuntvis side by side with the footage we ultimately captured and see a near-exact match. We did lots of speed retiming — cueing all of the actors, including our background performers, to pretend to move extra slow while we were still shooting slow-mo. The final result would feel as if we were going from normal speed to about 200 fps, even though we were only shooting 48 fps. Much of this action was captured with the aid of a 30' Technocrane if we wanted to make a move feel fast, we’d tell everybody to move slowly, and then we would perform the move quickly with our arm. The camera movement in that sequence is so bonkers compared to everything else in the movie.

For the Convention Center sequence, we relied on Panavision’s G Series lenses, and we had to light the scene for almost 360 degrees. The exterior of our location provided an ideal spot to place an 18K high up on an adjacent piece of architecture upstage for most of our shots. That broad, hard source worked for the majority of the scene. For certain reverse shots, If I decided I wanted to cheat more of an edge, as opposed to the scene being front lit, we had another lift positioned much farther out, in the opposite direction, to emulate that same light. We also rolled around five Arri SkyPanel S360-Cs with large Chimera bags, which gave us a mobile, big soft source. I would fill with fire sources wherever I could get them out of frame, and we added architectural lights behind pillars and within some of the architecture of the Convention Center itself. We aimed to imbue the scene with a blue-and-purple tone that I had established at our original arena in Atlanta, so I pushed in those colors from different nooks and crannies wherever I could get them in.

The scene also features some Busby Berkeley-esque nut-punch action, with Frank sliding under the legs of more bystanders, who fall away as he hits them. For this sequence, we worked at Wayne’s stunt studio, filming him and his stunt players to capture a variety of angles and options. Our rehearsals for this action continued on the Paramount lot, and Wayne subsequently developed a rig for the wide shot — comprised of a small sled, made from a plastic sheet, that was attached to a cable that would pull Liam or his stunt double as the action unfolded. For a shot that follows Drebin as he’s punching through this tunnel of nuts, we rigged the camera to a custom low-profile dolly that was essentially a sheet of plywood and skate wheels on a long run of pipes to be as close to the ground as possible. It was built long enough for Liam or his stuntperson to ride through everyone’s legs, and we hard mounted the camera right behind them and pulled the dolly with a line that was hidden by Liam’s body in the foreground. It’s all very crazy and silly, but we treated the material very seriously.

The Snowman Scene

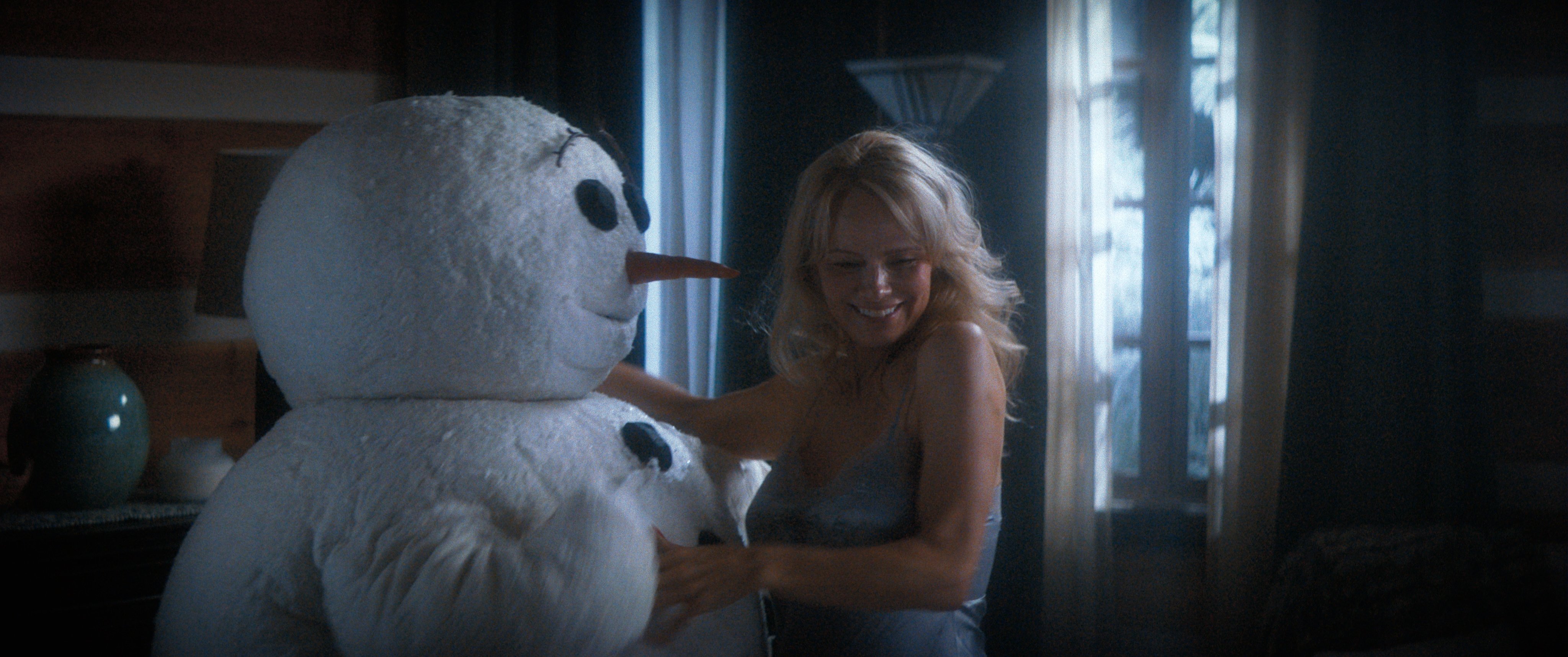

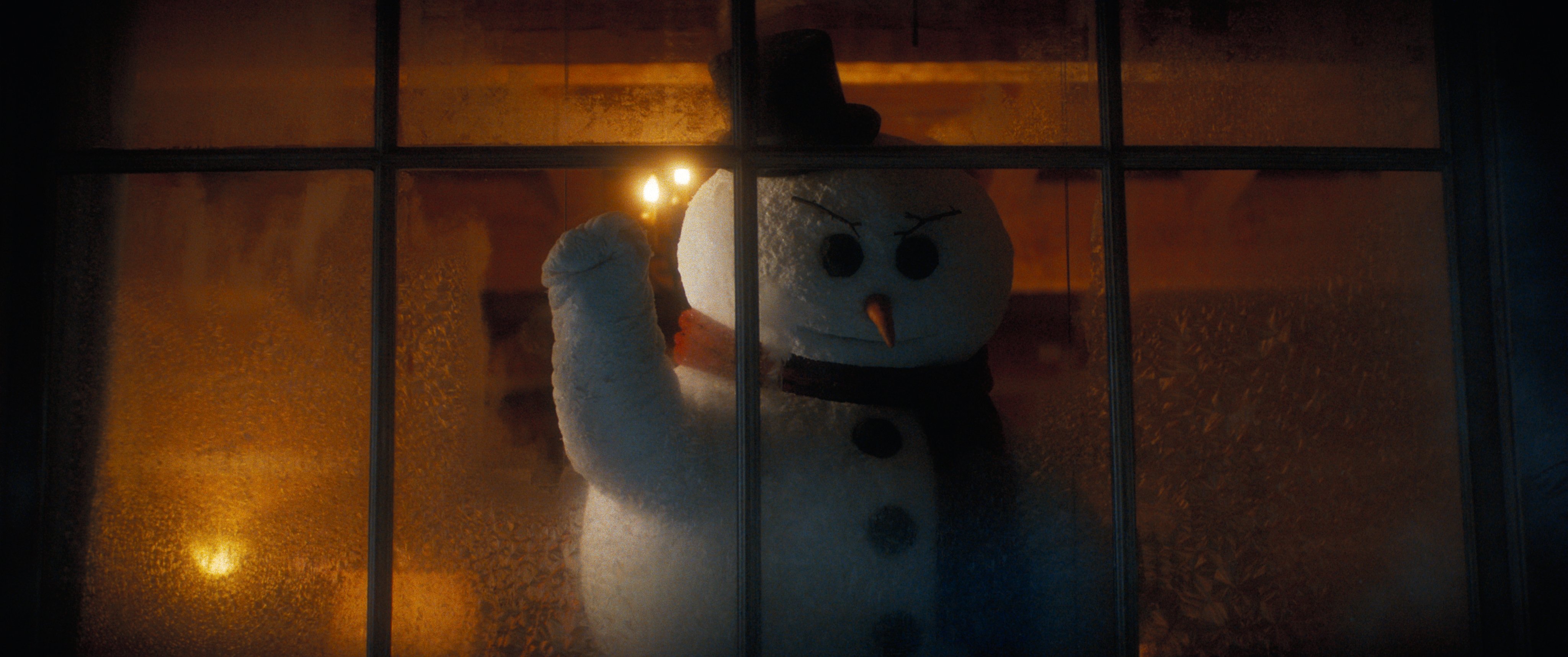

Still, nothing was crazier or sillier than our snowman sequence. The scene is basically a cabin-set romantic montage between Frank, Beth Davenport (Pamela Anderson) and a six-foot snowman. The team at the Jim Henson Company built us an animatronic snowman puppet, which was fun all on its own: One puppeteer performed practically, inside of the suit, while another controlled features like the face, mouth and eyebrows. We wanted the initial moments of the sequence to feel almost like a 1980s chewing-gum commercial or a cheesy romantic B movie. It’s very bloomy, and we used a heavy Tiffen 1/2 Pro-Mist filter for a dreamy look. Despite this being shot mid-summer in Atlanta, our effects people did a great job dressing our exterior cabin set to give it a snowy and wintry look.

Our A-camera operator BJ McDonnell, with whom I’ve worked with for years, captured the snowman’s POV shots on Steadicam. For a shot in which the snowman chases after Frank and Beth with a gun, BJ is actually wielding the pistol in the foreground; he’s physically holding out the snowman puppet’s arm, with the Steadicam rig in his other hand as he’s chasing Pam and Liam. It was an especially fun sequence.

It was such a blast to be a part of this film, and to be making it with old friends. I’m such a Naked Gun fan, and most of the time I just felt lucky to be on set.

The Naked Gun is now available to buy on digital and stream on Paramount Plus. All images courtesy of Paramount Pictures.