The Nazi Cartel: A Truly International Production

Filming the unbelievable story of a fugitive war criminal and the creation of the world's first narco state.

The cocaine trade is one of the largest and most violent criminal enterprises in the world, and in 1980, one of the most powerful Bolivian drug lords joined forces with one of the 20th century's most brutal war criminals to orchestrate the overthrow of the Bolivian government and establish the world's first “cocaine state.”

This is the story of The Nazi Cartel.

Photographed by cinematographers Alexander Gheorghiu and Jenny Lou Ziegel and directed by Justin Webster for Sky TV, Das Nazi-Kartell (its German title) is a three-part documentary series that centers on three men: the notorious Nazi war criminal Klaus Barbie (aka the "Butcher of Lyon"), posing as Klaus Altmann; Roberto Suarez, a Bolivian businessman who controlled 90 percent of the global cocaine trade at the time; and Michael Levine, an American undercover agent with the U.S. Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA), who seeks to expose and bring them down.

A Romanian native who immigrated to Germany in his youth, Gheorghiu studied cinematography at the Filmuniversität Babelsberg Konrad Wolf in Potsdam, which he characterizes as “an institution strongly shaped by the DEFA documentary tradition from the 1960s to the 1980s”, when the legendary film studio headquartered East Germany’s state-owned film studio. “At Babelsberg, documentary filmmaking was regarded as the key to translating reality into cinematic form,” he continues. “One of my professors once summed it up: ‘Every fiction film must carry a documentary within it if it is to succeed.’ In other words: It was a method of approaching fictional material as realistic.”

From 2001 to 2002, he studied at the École nationale supérieure Louis Lumière in Paris before graduating with a diploma in 2005. Since then, he’s worked as a cinematographer on numerous feature-length documentaries, including Staatsdiener and Aggregat, and the six-part series Höllental — the last of which earned him a 2021 German Television Award for Best Cinematography — all with director Marie Wilke for the Berlin-based production company Kundschafter Film, which also produced The Nazi Cartel.

While Barbie’s violent history in France during World War II is known to the well-informed, his activities in Bolivia remain much less familiar, particularly in postwar Germany.

Because the events that form the basis of The Nazi Cartel happened more than 45 years ago, the story would have to be told through the fragmentary recollections of protagonists now well into their 70s and 80s. The filmmakers’ challenge was to bring these distant events into the present by telling a complex story through multiple perspectives, in a realistic style, while emphasizing its thriller-like qualities.

“I think documentaries have become better and better at telling a story rather than recovering a story,” says Webster, whose credits include several award-winning Spanish language documentaries and series. “A character-driven narrative documentary is what I try to do. It’s not a question of fictionalizing or novelizing. It’s a lot of research, and then shaping and storytelling, so that you feel like things are happening in the present tense.”

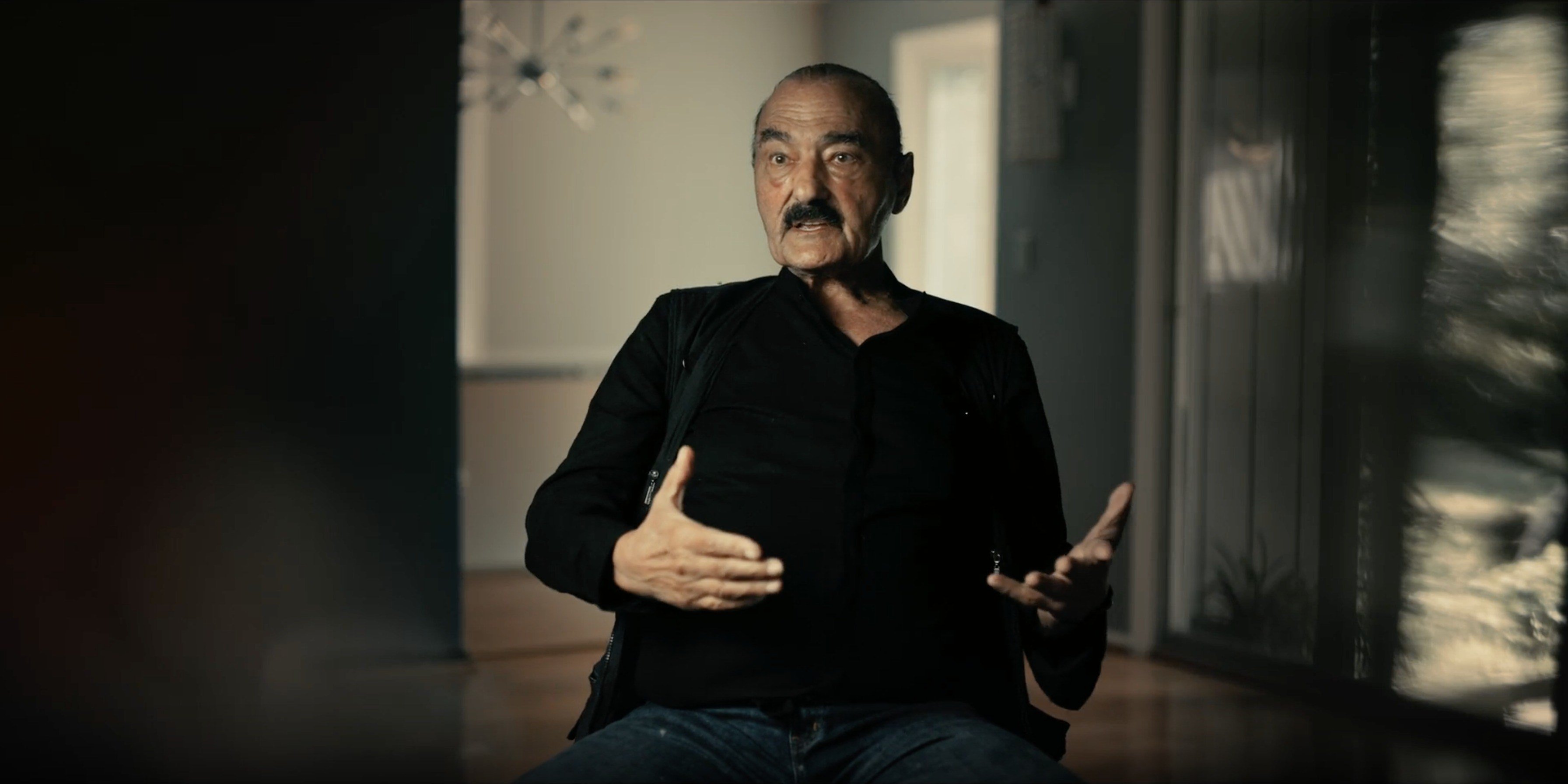

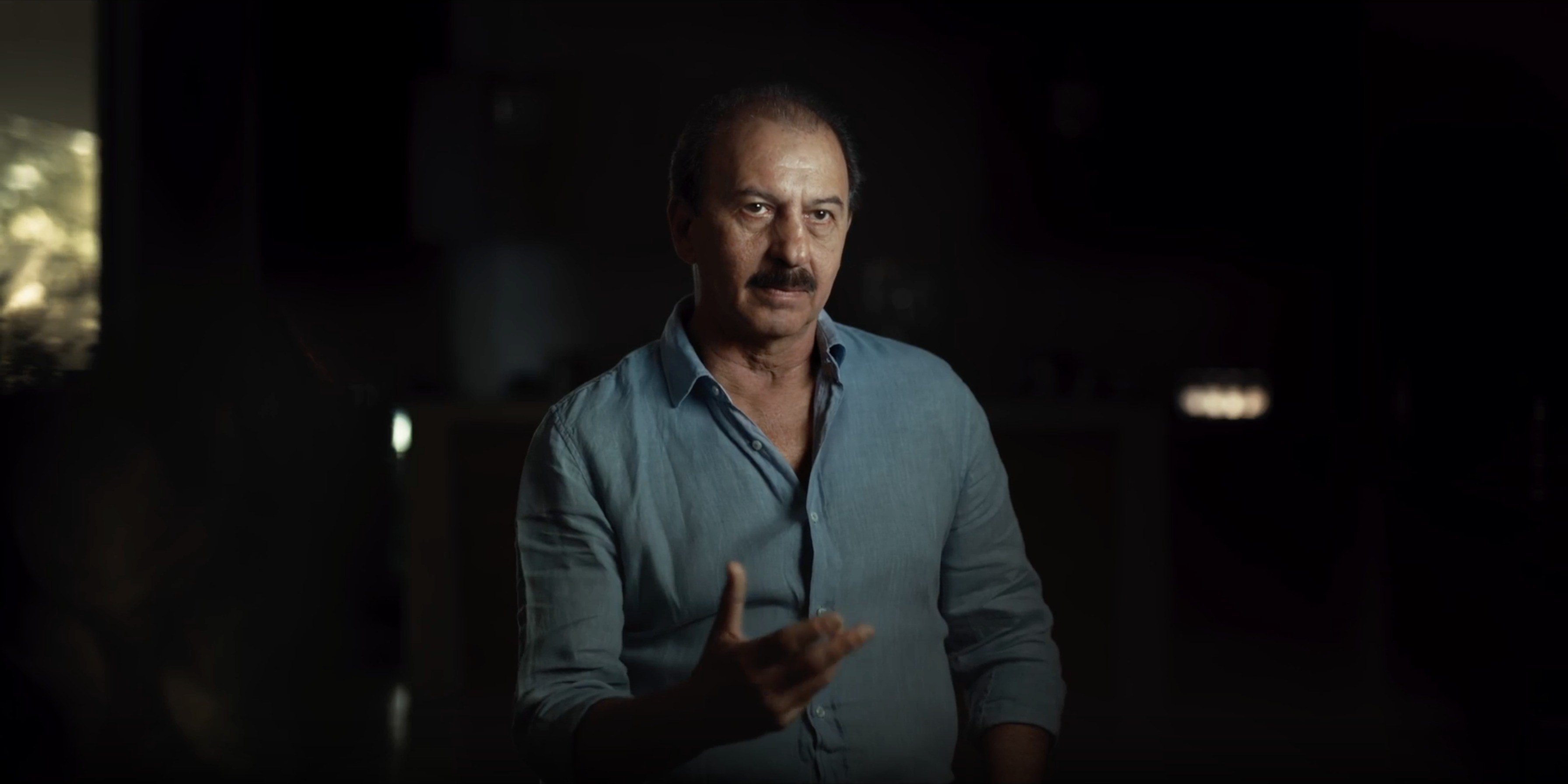

Interviews

The filmmakers started by interviewing people who were present for the events covered in the series, including government officials and members of Suárez’s family in Bolivia, and DEA operatives in the U.S. Gheorghiu’s visual concept for the interviews involved high contrast, deep blacks and carefully abstracted backgrounds.

Because most of the interviews were conducted in homes and other private spaces, Webster wanted to avoid any visible traces of domestic life that might distract from the testimony.

Gaffer Björn Susen used 2' x 3', 4' x 4', and 12' x 12' flags and 12' x 12' scrims to shape the background and isolate the subject in the environment, then lit them with an Aputure 1200x and 5' Octodome softbox. "This means the face is really visible, and the rest of the room mostly dark, but with a balanced contrast between foreground and the background," he describes.

Gheorghiu used a 50mm Sigma High-Speed prime at T2.8 with a Canon C500 Mk II set to full-frame mode, maximizing the amount of background blur, while still giving 1st AC Matthias Börner enough depth to pull focus. Gheorghiu notes that “[the Sigmas] perform exceptionally well, even at T1.4, providing strong image quality, full dynamic range and minimal aberrations.”

Additionally, he introduced colored Plexiglas panes, and glass and metal objects from the location in front of the lens, to create extra layers of distortion and abstraction around the edges of the frame. The cinematographer says, "This allowed us to respond spontaneously to each location, while keeping the focus firmly on the protagonists’ words."

Reconstructions

After two weeks of filming in the U.S., the German crew made a second visit to Bolivia in late 2024 to shoot the bulk of the series’ dramatic reconstructions with a local cast and crew, this time in the lowland department of Santa Cruz, where Suarez’s operations were once based.

With most of the interviews conducted, Gheorghiu and Webster knew what they wanted to stage, even though it was clear from the outset that there would be little time to organize the reconstructions once they were in the country. Some of the main locations were locked in, but others had fallen through or had yet to be cast. There was no film production infrastructure to speak of — though plenty of experienced production crewpeople — and political instability, coupled with fuel shortages, made travel in and out of Santa Cruz difficult, so plans were dropped as easily as they were made. This required Gheorghiu to adapt quickly to scene and location changes, "and my documentary background proved invaluable," he says.

The filmmakers’ approach to filming the reconstructions rested on two elements: depth of field and camera movement. Webster notes that the reconstructions are suggestive rather than precise. "We used a very narrow depth of field to give the viewer a feel for what the scene was about," he explains. "When you become too explicit, it becomes very obvious that what you’re filming isn’t real, whereas the suggestive frame focuses only on the elements that you actually know were there."

As an example, he points to a scene set in the back room of a bar in Santa Cruz that Barbie’s mercenaries — “Los Novios de La Muerte”, aka “The Bridegrooms of Death” — transformed into a drug-fueled Nazi shrine. The filmmakers knew the back room actually existed from testimonies that described it, but none of them ever saw it, so they had Bolivian production designer Lukas Paulo Aranda Marquez recreate it in total, then focused on the scant details they had — a glint of light off the barrel of a rifle, lines of cocaine on the table, bottles of alcohol, the bare flesh of a prostitute. "The rest is merely suggestive," Webster remarks.

“A too sharp or overly concrete image can reduce imaginative space,” the cinematographer adds. “A blurred image, by contrast, can make room for interpretation and draw the viewer in.”

“I had to simply work out in a fast and spontaneous way the complex sequences where many things were happening, and the cinematic resolution unfolded mostly within a single shot.”

— Cinematographer Alexander Gheorghiu

Gheorghiu — and Ziegel, in the production's first visit to Bolivia — used the Ronin 4D all-in-one 4-axis gimbal/6K camera for its speed and flexibility, and Leica Summilux and Summicron still lenses. “Their vintage 35mm look matched the atmosphere of the 1980s setting perfectly, with their flare, bokeh and contrast characteristics,” Gheorghiu says.

Camera movement pursued the same goal by different means, says Gheorghiu: to immerse the audience directly in the narrative. "I believe this blurring of boundaries is a central quality of contemporary reenactment cinematography — and with The Nazi Cartel we sought to take it a step further." The camera tracks and floats through each scene, sometimes to reveal fine details, but more often than not moving to obscure them.

"All the protagonists’ movements within a scene had to be connected, and everything that happens in a scene can only be captured once," Gheorghiu describes. "I had to simply work out in a fast and spontaneous way the complex sequences where many things were happening, and the cinematic resolution unfolded mostly within a single shot."

Balancing these elements with the sometimes guerrilla conditions on set demanded intense focus and technical skill, says Gheorghiu, especially from his camera assistant.

"The shallow focus was not the main challenge for me. This is something I’m used to, although usually I’m keeping faces in focus. Here, it was mostly the opposite," says Börner. "The real challenge was to help Alex and Jenny as well as I could to get the shots Justin wanted. With the small crew and limited resources for props, locations, cars, actors and extras, there is a fine line between a shot that looks cheesy and one that sells the illusion."

To help sell the illusion, reconstruction footage needed to maintain the visual tone established by archival photos, film, and video material from the late '70s and early '80s. With best boy Matthias Hildebrand and Bolivian gaffer Guillermo Angel Torrez Malina, Susen employed a minimal amount of lighting sources in most scenarios, mainly Astera Titan Tubes and existing practicals, and sometimes an Aputure Storm 1200x.

"We took it mostly as an available light situation," says Susen. "What we were really interested in was colors from this period. Color in the '70s was a lot of green and orange. So, this was the color balance we were looking for, especially for the night shots." (The color grade was performed by Artem Stretovych at The Post Republic in Berlin.)

Both Gheorghiu and Webster agree that the timing of The Nazi Cartel’s release feels relevant to current events, though for different reasons. "It chimes a bit, this combination of business ambition and fascism, with a distaste for democracy," Webster observes.

One of Gheorghiu’s main motivations for joining the project was the opportunity to shed light on Barbie’s lesser known — but no less heinous — crimes, lest they be forgotten by younger generations of viewers. "In conversation, people are often astonished that Barbie had such a significant and lasting influence on politics in South America," he says. "I was glad to be part of a team that’s trying to change that."