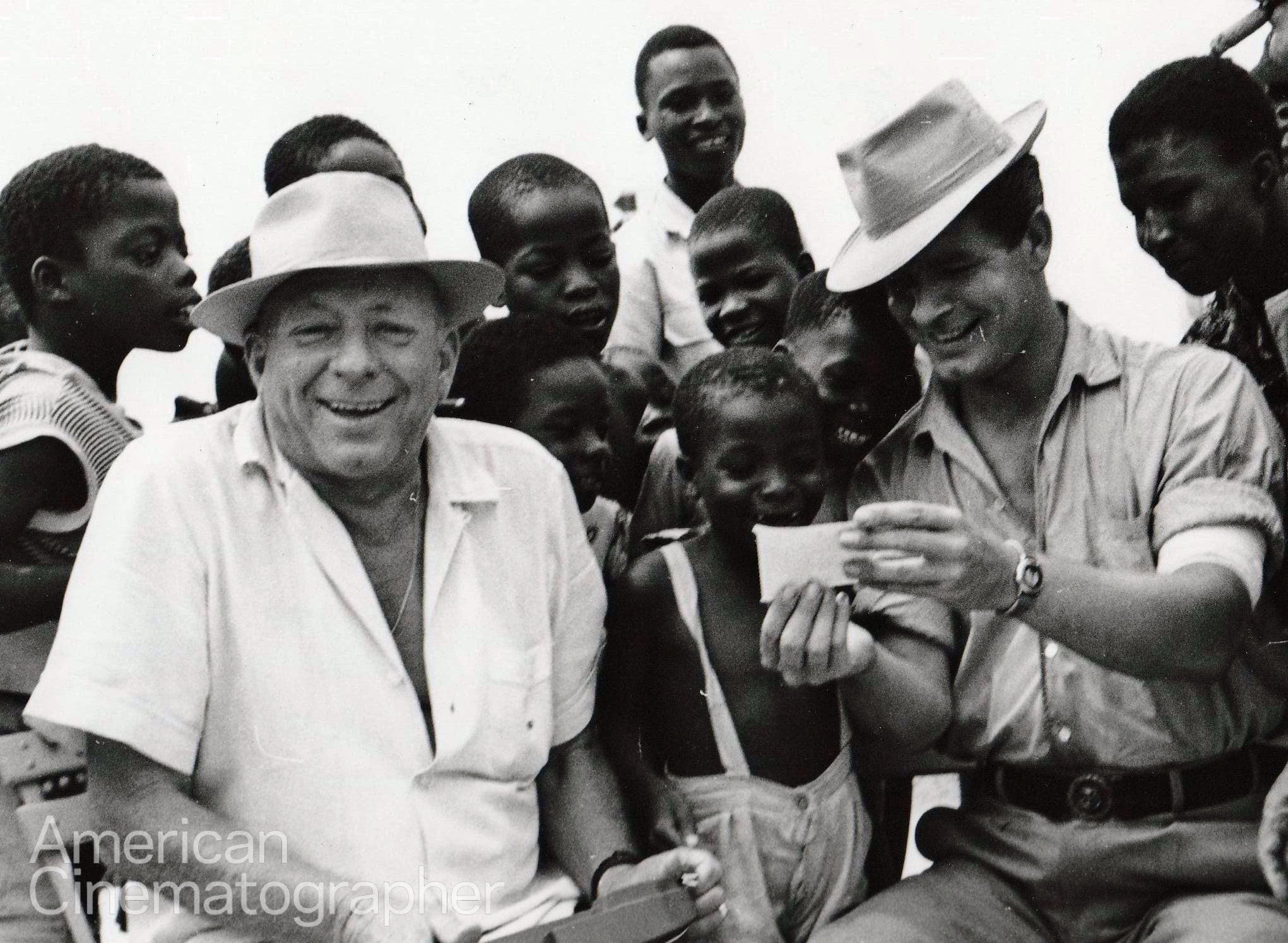

Aces of the Camera: William C. Mellor, ASC

“Aces of the Camera” was a profile series that ran in AC for several years starting in the early 1940s. This article was originally published in AC Dec. 1941.

Director of photography Billy Mellor, ASC is typical of Hollywood’s younger generation of cinematographers. Young he certainly is; official figures show he’s just barely beyond draft age, and in spite of all his efforts, he looks deceptively younger than that. Yet at the same time, he is acknowledged as one of the industry’s most skillful and versatile masters of the camera. In the seven years he has been a full-fledged director of photography, he has climbed steadily to the forefront, and proven his versatility on everything from westerns and comedies to Bing Crosby and Bob Hope musicals, tense dramas, and Dorothy Lamour Technicolor opuses. He’s probably photographed more pictures starring Paramount’s glamor-girl than any other cinematographer in the industry.

“The only way you can learn what to do under any given situation is by experience — and lots of it. The only way to get that experience is in actual practice, on real production.”

He’s a bit touchy, I think, on his youth, and on the fact that virtually the whole of his cinematographic career has been spanned in the relatively few years since the advent of sound. “But,” he says, “maybe there’s a good side to it, too. I remember a lot of the longer-established fellows had quite a time adjusting themselves to such technical innovations as sound, panchromatic film and the moving camera. Professionally speaking, I pretty well grew up with them; and if I don’t have a lot of pioneer experience to draw on, I also didn’t have a lot of pioneer traditions to un-learn.

“And I did have about the best cinematographic schooling anyone could ever want. For six or seven years I worked as operative cameraman with Victor Milner, ASC, who is one of the industry’s all-time masters of lighting, and, in between, I worked with Charles Lang, ASC and other top-flight cinematographers on the Paramount list. Those fellows taught me things I could never have learned in any ‘school’ of photography.

“That’s something I try to impress on hopeful youngsters who write me — as they do most other directors of photography — asking how to prepare themselves for a career in cinematography. They all seem to ask if there’s any ‘school’ I could recommend. The truth is, there isn’t — unless you count the school of practical experience which taught most of us. Just figure it out for yourself: cinematography is something that just can’t be reduced to a set of rules and forms. You do things differently on every scene and setup. The only way you can learn what to do under any given situation is by experience — and lots of it. The only way to get that experience is in actual practice, on real production.

“To teach that way, a school would have to engage regularly in actual production, which would call for an investment of several hundred thousand dollars in basic equipment, to say nothing of the little matter of production costs which would be equally large. All that would mean the school would have to have a tremendous endowment, or charge an enormous fee. And then— where would the graduates go in an industry already seriously over-manned? No, much as I hate to throw cold water on the aspiring hopeful, there’s no school but the long, hard school of experience.”

Mellor’s attitude toward his work is characteristically modern. “One of the biggest mistakes a cinematographer can make,” he’ll tell you, “is to try to reduce his work to fixed standards, and do things this way or that just because he happens to be on a certain type of picture. You can’t just say, ‘This one’s a heavy drama — I’ll go to a low-key lighting and fairly heavy diffusion,’ or ‘This is a melodrama, so I’ll light for strong contrasts and scary shadows,’ or ‘This is a comedy, so I’ll do it in a high key.’ Maybe you can work successfully by formula for a while: but then something a bit out of the ordinary is going to come along — and then where’ll you be?

“For instance, right now I’m making a picture like that. It’s a melodrama. But it’s also a Bob Hope comedy. So what — ? If I light it by formula for melodrama, I’m likely to lose some of Bob’s funny-business in the shadows. If I light it for comedy, I’m sure to lose the melodramatic suspense that forms a contrasting background for Bob’s comedy. Incidentally, I have to keep co-star Madeleine Carroll looking her glamorous best, too.”

“The really important thing is to match the mood and style of the photography so closely to the story and action that the audience isn’t conscious of whether the photography is either good or bad.”

“So what I’m doing is to blend my technique to get both effects at once. I’m lighting my sets primarily for the melodramatic mood — strong contrasts, heavy shadows, and all that. But I’m seeing to it that the shadows just aren’t where Bob Hope is going to be doing his stuff. Not that I’m giving him conventional comedy lighting — that would stick out like a sore thumb, and make the audience at least subconsciously realize the picture was badly photographed. But I’m making certain that wherever in the scene Bob may be playing, there’s always adequate illumination so his ‘business’ won’t be lost — and that there’s always a good, legitimate reason for that illumination, too. That’s just as important!

“As for Miss Carroll, it’s fortunate that this business of glamor camerawork is done largely in the closer shots. That way, I can subordinate the background, keeping whatever mood I need to match the action, and at the same time light her as is best suited to her, merely matching the key to suit the rest of the sequence.

“The really important thing is to match the mood and style of the photography so closely to the story and action that the audience isn’t conscious of whether the photography is either good or bad. Of course, if photography in a picture is downright bad, or crude, they’ll notice it. But it isn’t always realized that they’ll notice it, too, if the photography is too perfect — to pictorial. One is really just as bad as the other, only on opposite ends of the scale. The minute the audience begins to notice consciously what you’ve done with your camera, they’ll begin to let their attention slip from the story. And that’s bad, believe me — very bad, for it means the cinematographer is working against the rest of the troupe, rather than with them, to give the audience entertainment in the most complete form.”

Following this profile...

Mellor turned out his most remembered and revered works in the years after this profile was published, earning four Academy Award nominations, for A Place in the Sun (1952), Peyton Place (1958), The Diary of Anne Frank (1960) and The Greatest Story Ever Told (1966). He won the Oscar for both A Place in the Sun and Anne Frank. He also shot the classic Giant (1956), starring James Dean, Rock Hudson and Elizabeth Taylor.

During the production of The Greatest Story Ever Told, Mellor suffered a fatal heart attack. He was just 59.