John Simmons, ASC: Commitment to Artistic Voice

The Society honors the cinematographer with its President’s Award for his creative achievements and steadfast devotion to fostering an inclusive filmmaking community.

John Simmons, ASC has had a camera in his hand for some six decades. He began as a still photographer — producing work that is now in the collections at major museums around the country — and is today an award-winning cinematographer with credits in documentaries, commercials, music videos, features and television. Throughout his career, his creative journey has been anchored in a commitment to mentorship that has impacted countless other cinematographers.

He will be presented with the ASC’s Presidents Award during the Society’s annual gala on Feb. 23.

“I feel so fortunate now,” Simmons says over lunch at a favorite Himalayan restaurant in Los Angeles. His conversation with AC continued over stops at his nearby art studio and a gallery in Inglewood that was preparing an exhibition of his photography; a brief visit with his wife, Cynthia; and a stop at a downtown underpass to drop off supplies to someone living on the street (“a little humanitarian gesture,” Simmons says). Then the cinematographer headed to Universal Studios to prep for a sitcom. “Whether I’m working with my crew on a show, in my studio printing some of my photographs, or hanging out with Cynthia at home and working on a collage, everything I do is related to creating images,” he says.

A Developing Eye

Born in Chicago in 1950, Simmons developed an artistic consciousness early. His teen years aligned with the tumultuous cultural and social upheaval of the 1960s. “Artistically, people were expressing themselves in new ways,” he recalls. “Being on the fringes of that, my friends and I wanted to be a part of it. We had musical instruments we tried to play; we went to a lot of concerts; we read poems; we tried to have all the hip books in our pockets.”

But taking pictures was the form of expression that clicked for Simmons. He was introduced to photography by a childhood friend’s older brother, Robert “Bobby” Abbott Sengstacke, who became an award-winning photojournalist. The Sengstacke family owned the Chicago Daily Defender, the oldest Black publication in the country. When Simmons was 15, he tagged along with the Sengstackes to a newspaper-publishing convention in New York and borrowed one of Bobby’s many Nikon cameras. “I asked Bobby if I could shoot with one of them around the convention. We processed the film, and Bobby said, ‘Whoa, you got an eye!’ Then he took me under his wing, and I started working in the darkroom.”

“ASC membership and the participation in that membership is the lifeblood that keeps the ASC and its legacy going. It’s been very easy for me to participate and give my time to the Society because it’s not only important to the art of cinematography, but it also allows me to make a difference in my community of cinematographers.”

By the age of 16, Simmons was taking pictures for the Defender all around Chicago, including anti-war protests and the 1968 Democratic National Convention. One of his shots was featured in an exhibition at the Chicago Public Library, an honor that Sengstacke helped arrange. Sengstacke also helped secure Simmons’ undergraduate education at Fisk University; when the older photographer became artist-in-residence there, he asked 17-year-old Simmons to be his assistant.

While studying fine arts at Fisk, Simmons took filmmaker Carlton Moss’ class “The Image of the Black Man in American Cinema.” It changed the course of his life. “One day I showed Carlton my work, and he told me I was a cinematographer. I had never heard that word before.” On Simmons’ behalf, Moss reached out to his friends Cal and Roz Bernstein, who owned the L.A. production company Dove Films. “They sent me an Arriflex S16, film, a changing bag, a tripod, extra magazines, a subscription to American Cinematographer and the American Cinematographer Manual.” With that, Simmons began practicing his craft.

Making It Work

Simmons started assisting Moss on educational documentaries, and in 1976, he created a documentary based on Two Centuries of Black American Art, the influential traveling exhibition curated by David Driskell, one of Simmons’ mentors at Fisk.

Moss helped Simmons secure a scholarship to the University of Southern California and a job at Dove Films, where Vilmos Zsigmond, ASC was the head cinematographer. Simmons recalls he was the only Black student in the film department at USC. And as the only Black person on the grip trick at Dove, he was subjected to a barrage of racist jokes despite the progressive atmosphere the Bernsteins tried to cultivate. Simmons recalls, “I called Carlton and said, ‘I don’t think this is the right place,’ and he said, ‘Do you know any Black people who are making films?’ and hung up. So basically, if I wanted to work, I had to make it work in this atmosphere.” His passion to learn and develop his craft pushed him forward.

After graduating from USC, Simmons continued at Dove. “There were always amazing cinematographers around, and some of those cats, like Sven Nykvist [ASC], Jordan Cronenweth [ASC] and Melvin Sokolsky, were very generous and supportive. Unfortunately, some others made it more difficult.” He also took on PA truck gigs — “picking up equipment, craft service, lab runs and eventually doing second-assistant work slating, loading mags, getting coffee and never saying no” — and worked at the educational-film studio Wexler Films, where Sin Hock Gaw trained him as a camera assistant. “I’ll always be thankful to Sin,” Simmons says. “He faced a lot of racism in the industry as well, and he taught me a lot.”

Crewing Up

In the early 1980s, Simmons stepped in to finish Stevie Wonder’s video for “Ribbon in the Sky.” It was a major break. “Walt Lloyd was the original cinematographer,” he recalls. “I was a second camera operator on the video, and I finished it when they added a pickup day. That began a long relationship with the production company. After that, I did another Stevie video called ‘Do I Do,’ and then I started doing a ton of music videos.”

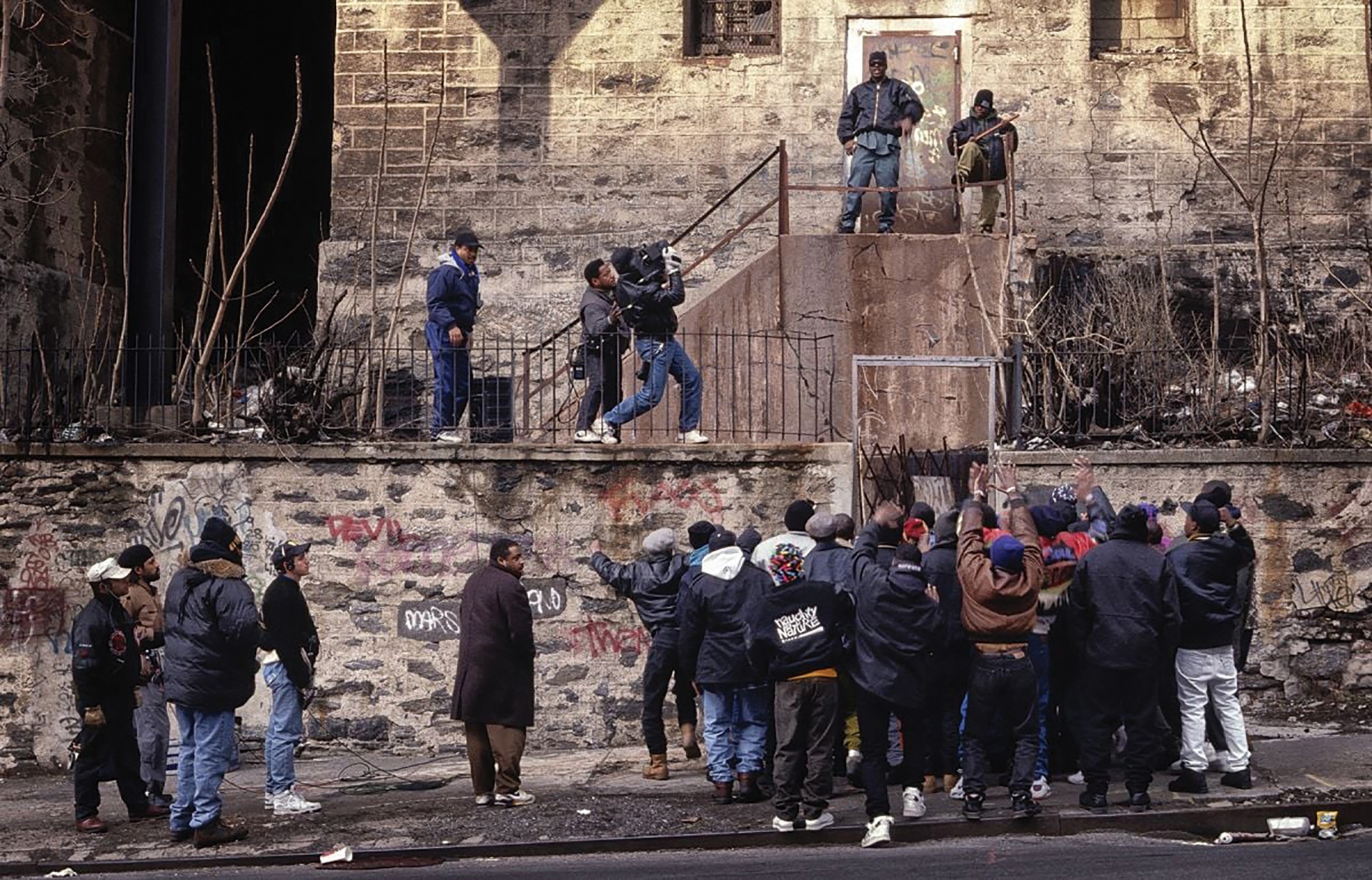

Throughout the 1980s and ’90s, he shot videos for Tupac Shakur, Dr. Dre, Ice Cube, Snoop Dogg, Jessica Simpson and many others. “Making videos was creatively very free, and I was able to make my crew look like a representation of everybody in the world — I had women and people of color working with me as my operators and assistants. That was important to me.”

Around that time, Simmons started directing commercials through Film Syndicate, which was owned by Bryan Johnson. With financial backing from the Bernsteins, Simmons and Foster Corder established the commercial-production company Blackbird Film, which prioritized hiring directors and crew from underrepresented groups. Their clients included McDonald’s and the California State Lottery.

In the mid-1990s, Simmons collaborated with Spike Lee on a number of commercials, including the iconic Diet Coke ads that featured the R&B group En Vogue. “I got called for a lot of jobs after that because I had worked with Spike,” he says. Simmons also began working with Debbie Allen, a creative relationship that has continued across various projects for decades.

“I was able to make my crew look like a representation of everybody in the world — I had women and people of color working with me as my operators and assistants. That was important to me.”

Higher Ground

Simmons first feature-cinematography credit was Tim Reid’s Once Upon a Time…When We Were Colored, which tells the story of a family living in the segregated South. Simmons worked closely with Reid to create a strong visual language for the film. “Vermeer, Caravaggio, Hopper — those were our visual references. We were really trying to paint that thing. We shot in North Carolina, and it felt like every Black actor in America was there: Phylicia Rashad, Bernie Casey, Al Freeman Jr., Taj Mahal. Everybody was giving everything they had to make sure that film was a piece of artistry.” The budget was less than $2 million, and it was shot in fewer than 20 days. For Simmons, it led to more work that gave voice to the Black experience, including Reid’s feature Asunder, the TV movies Ruby Bridges and Selma, Lord, Selma, and a number of documentaries.

In the late 1990s, Simmons shot his first primetime multi-camera series, The Hughleys, after cinematographer Bruce Finn asked him to step in. That kicked off a long, robust career in multi-camera sitcoms, which includes episodes of Lopez vs Lopez, Grey’s Anatomy, The Conners, Family Reunion, iCarly, Pair of Kings, Jonas and All of Us.

In 2004, Simmons was inducted into the ASC, “a major milestone in my life.” He explains that the process began nearly a decade earlier, when he met Steven Poster, ASC at an event by chance. “I told Steven I’d just made my first feature, and he guided me through making an answer print because I hadn’t done it before. He became my guru for that project.” Sometime later, Francis Kenny, ASC called Simmons to say he was on the Society’s radar. “Just hearing that they were interested felt amazing,” Simmons says. “To be acknowledged like that, I felt suddenly like maybe I am a cinematographer!”

Simmons won his first Primetime Emmy in 2016 for Nickelodeon’s Nicky, Ricky, Dicky & Dawn. “When I won, I took my key grip and my gaffer up on stage with me because those are the guys I do it with, and we’ve been working together for 20 years. If I could have, I would have brought the whole crew up.” In 2020, he won another Primetime Emmy, this time for Netflix’s Family Reunion, for which he also won a Children’s and Family Emmy in 2023. (He has also directed two episodes of the show.) His honors also include two regional Emmys, for the PBS documentary Finding Home: A Foster Youth Story and Hollywood’s Architect: The Paul R. Williams Story. He has served on the Television Academy’s Board of Governors for six years.

The Mentor Mentality

In 2016, he and Cynthia Pusheck, ASC were named founding co-chairs of the ASC Vision Committee, which was initiated by Richard Crudo, ASC president at the time. The committee supports underrepresented cinematographers and their crews and encourages an industry-wide initiative to hire talent that reflects the diversity of society at large. “We put together workshops and panel discussions, and we got a lot of support from Richard,” Simmons says. “We want to be able to talk to people and help them navigate their careers — to let them know they aren’t alone.”

Simmons has also been an adjunct professor in UCLA’s School of Theater, Film & Television for 26 years. It is not unusual for students he taught decades ago to stay in touch with him. He proudly notes that two former students, Lisa Wiegand and Quyen Tran, have become ASC members. He finds mentoring particularly gratifying, and has made a point of helping cinematographers from all walks of life. “The wonderful thing about mentoring is that it’s like throwing a rock in a lake — those rings that ripple on the surface continue, and they touch others as well.”

In 2019, Simmons was honored with the ASC Mentor of the Year Award, underscoring his impact on others. “A little before that, Cynthia and I participated in a panel discussion at the ASC called ‘Changing the Face of the Industry.’ A number of people stood up and mentioned that I was their mentor, and finally the moderator asked, ‘Who in this room has been mentored by Johnny Simmons?’ Three quarters of the room stood up! I couldn’t believe it.”

When the ASC inaugurated the Carl Kresser Heart of the Community Award in 2023, Simmons became its first recipient. “I was so impressed with that because, again, it’s connected to mentoring and the spirit of contribution. That award and the Mentor of the Year Award are so important to me because they acknowledge a concern greater than myself. A life worth living is a life that touches other people.”

Legacies Preserved

Though Simmons had been a photographer for decades, he fell out of the habit of printing his pictures regularly or exhibiting his work until Charlie Lieberman, ASC, a fellow photographer, saw some of his prints in 2014. Lieberman connected Simmons with gallerists, and that year, Simmons had his first exhibition since the 1970s at Perfect Exposure Gallery in L.A. “The show was supposed to stay up for a month, and it was there for more than two months,” Simmons says. “Close to 2,000 people signed the guest book, and everything sold.”

“The wonderful thing about mentoring is that it’s like throwing a rock in a lake — those rings that ripple on the surface continue, and they touch others as well.”

Martha Winterhalter, the former art director and publisher of American Cinematographer, connected Simmons with someone at The Getty, which became the first major museum to add his work to its collection. His impactful black-and-white photographs and colorful collages are now in the collections of The National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C.; Harvard Art Museums; High Museum of Art in Atlanta, and others. “My art is no longer isolated … it’s found its place where its legacy can be preserved,” he says. His photography was also recently included in the exhibit “The ’70s Lens” at the Smithsonian National Gallery of Art.

Receiving the ASC Presidents Award is another milestone. “To me, ASC membership and the participation in that membership is the lifeblood that keeps the ASC and its legacy going. It’s been very easy for me to participate and give my time to the Society because it’s not only important to the art of cinematography, but it also allows me to make a difference in my community of cinematographers.”

Further Reading