Andrzej Bartkowiak, ASC: When Prep Met Opportunity

The 2025 ASC Lifetime Achievement Award honoree counts himself fortunate to have had a chance to shine.

Andrzej Bartkowiak, ASC, recipient of the Society’s 2025 Lifetime Achievement Award, has shot an array of genres and styles for a “Who’s Who” of directors — among them Sidney Lumet, Barbra Streisand, Taylor Hackford, James L. Brooks, John Huston and Roger Donaldson.

While many directors of photography end up typecast after their first major success, he has glided smoothly from legal thrillers (Prince of the City, The Verdict) to character-based dramas (Terms of Endearment, The Mirror Has Two Faces) to comedy (Prizzi’s Honor, Twins) to high-octane action (Speed, Dante’s Peak) to stories that are not easy to classify (Falling Down, The Devil’s Advocate). And that doesn’t even touch on the 2,000-plus commercials he has shot, many of which are standout examples of the craft.

Bartkowiak was contacted by ASC President Shelly Johnson with the news of his award and the honoree was both appreciative and surprised the Society is recognizing him this way. There’s also humility in that he credits a lot of his success to chance. “I believe the old saying that 50 percent of success is luck. There could be plenty of people with more talent who never got a break. You’ve got to be good, but if you don’t get the opportunity, people never know it.” The honor will be presented during the ASC’s annual gala on Feb. 23.

Bartkowiak’s future in the American film industry was certainly not a given when he was growing up in Łódź, Poland. He was attracted to creative endeavors — he played in a rock band, wrote for his school newspaper, and intended to study painting at the Kraków Academy of Fine Arts — but one day his interests came into sharp focus when he visited a neighbor. He recalls, “The midwife who delivered me lived a few houses away, and her son was attending the Łódź Film School. She had blown-up pictures from various movies and a camera on a tripod in her house. That’s really what made me think about film as a combination of everything I was interested in all at once — music, story and pictures! And that prodded me to want to attend the film school.”

“Anybody who says, ‘I made this movie myself,’ is full of s---. You depend on a crew every moment of every day.”

Total Immersion

Upon enrolling in the prestigious Łódź institution, he soaked up important movies from all over the world — adding to his established background in studies of painting, sculpture, writing and photography — with an eye to developing a real understanding of the visual arts and an appreciation of master practitioners. This forever informed the way he thought about cinematography, and occasionally served to enhance communication with collaborators. For example, Lumet referenced Caravaggio’s use of chiaroscuro as a starting point for discussing The Verdict. Hackford brought up the hues found in much of Goya’s work during prep for The Devil’s Advocate. Being steeped in classic works, he says, offers an invaluable foundation for any artist. “Rather than always reinventing the wheel, you can make it better.”

An enormous part of his education at Łódź consisted of making films — not just discussing them — and the school provided resources. Bartkowiak notes, “It’s government funded. If you need pyrotechnics, a lot of trucks or even an army, you get it. We shot on the same stages that major filmmakers from the country used. The school hired professional grips, whatever you needed, and it was all completely paid for.”

Early Days in America

A documentary project soon took Bartkowiak to Mexico, and then, eventually to Mamaroneck, New York, where he worked painting houses and doing other odd jobs. A gig driving for a diplomat brought him to the attention of Polish actress Elżbieta Czyżewska, who was married to New York Times reporter and author David Halberstam (The Best and the Brightest). The couple took an interest in Bartkowiak, and soon he was living with them and spending time with other members of the American literati, including Kurt Vonnegut and Gay Talese. “David taught me how to be an American,” Bartkowiak declares. “He co-signed for my first American Express card and showed me how to build credit.”

Bartkowiak was soon working on commercials crews after being given a major break by director and producer Lear Levin, and he quickly moved up the ladder to shoot and sometimes direct them. Over the next 15 years, he served as cinematographer or director/cinematographer on a huge number of spots for such clients as Chrysler, IBM, Coca-Cola, Pepsi and American Express. He landed his first feature, Ivan Nagy’s Deadly Hero, in 1975, starring Don Murray, James Earl Jones and newcomer Treat Williams. The project didn’t quite launch his Hollywood career, Bartkowiak recalls, but “it gave me confidence — and it gave other people confidence in me.

Among them were filmmaking partners Ismail Merchant and James Ivory, who hired Bartkowiak to shoot the short film The 5:48 (1979) for the PBS miniseries 3 by Cheever, starring Laurence Luckinbill and Mary Beth Hurt. “It’s a good-looking show,” the cinematographer says. “I was doing things that not many people were doing in those days.” He notes that the “monumental invention” of the lightweight Panavision Panaflex camera made handheld work much less cumbersome, and he took advantage of this, incorporating a lot of handheld work into the project.

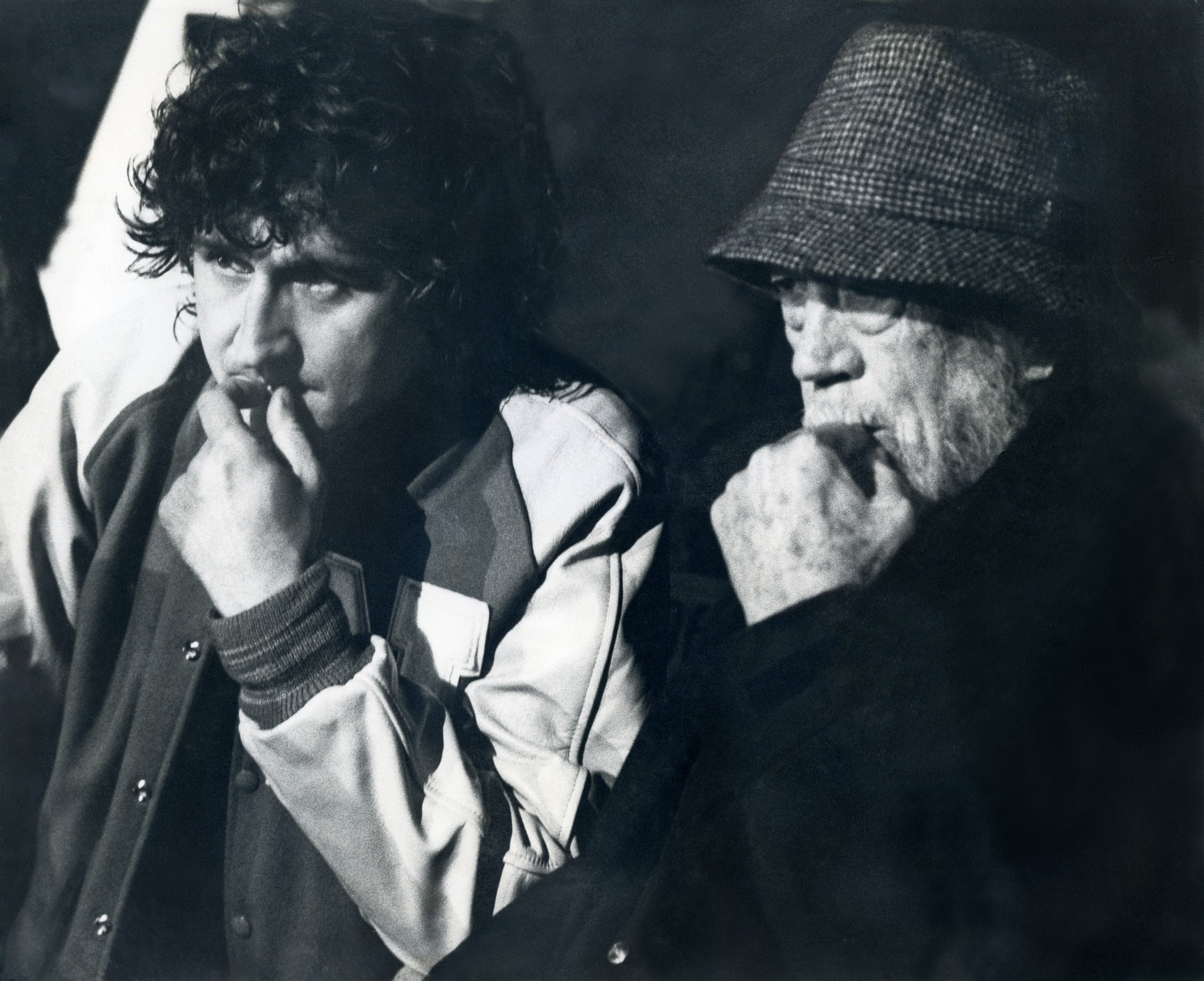

Lumet Calls

Months after wrapping that job, Bartkowiak brought his grandparents over from Poland and took them sailing around the Virgin Islands. Upon checking his answering service from the dock, he learned that producer Burt Harris, one of Lumet’s frequent collaborators, was trying to reach him on the director’s behalf. Apologizing to his guests, Bartkowiak grabbed the next flight to New York.

Lumet, it turned out, had been quite impressed with the cinematographer’s use of day-for-night photography on The 5:48, and he was looking for a cinematographer for his upcoming police drama Prince of the City.

In the photochemical days, before attributes such as color, saturation and contrast could be fine-tuned individually in post, good day-for-night work was particularly exacting, requiring a well-thought-out use of NDs and grads and underexposing the negative to within an inch of its life. It was often done poorly, and Lumet took notice of the quality of Bartkowiak’s work with that technique.

After a short meeting, Lumet hired Bartkowiak, and the cinematographer would remain a key collaborator over the course of 10 more features. “Sidney was a genius — an enormous amount of what I know about directing, I learned from him,” says Bartkowiak, whose credits in the directorial arena include the features Romeo Must Die and Doom.

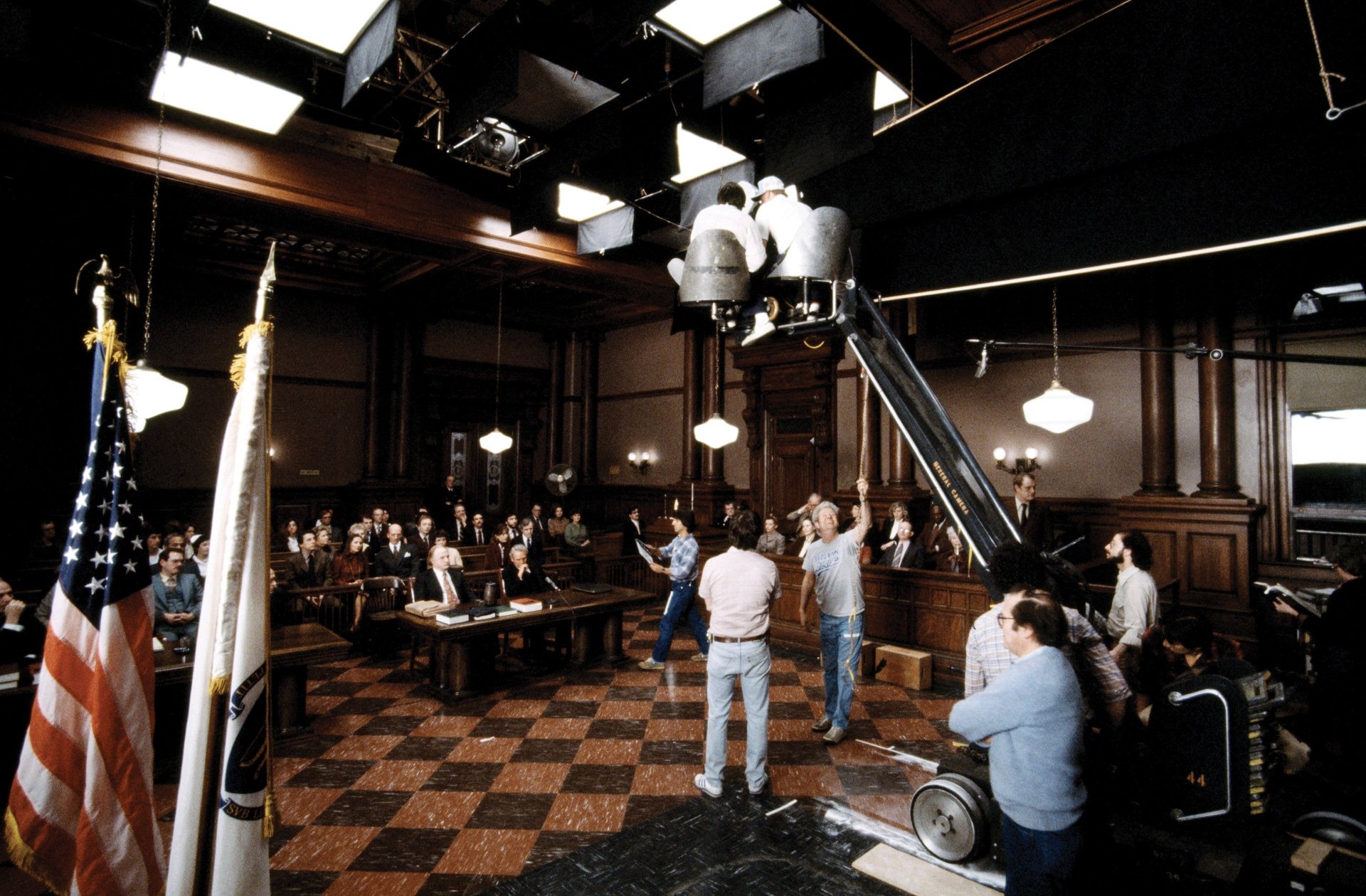

Lumet was known as one of the few major film directors who insisted on rehearsing, usually for at least three weeks, so that actors and department heads could work out a lot of what would otherwise be done during shooting. “We prepped so much on his films that we usually finished under budget and ahead of schedule,” Bartkowiak recalls. He adds with a laugh, “Everybody called him Pac-Man,” gobbling up the day’s work.

Bartkowiak became accustomed to preplanning light placement and working with three lighting crews — additional lighting techs to pre-rig and then a third to strike. When shooting, Lumet wanted all the walls to fly, ideally vertically, so they could move out of the way with maximum efficiency. The work zipped along, and Bartkowiak’s crew might be given less than 10 minutes to turn around for a reverse shot.

“I really mastered lighting that way, which later helped me to shoot with multiple cameras,” Bartkowiak says. He is perfectly comfortable shooting with two, three or more cameras, and he says he has even acclimated some “single-camera directors” to covering scenes with multiple cameras. “You can have flawless cuts where everything matches perfectly.”

Working with Lumet also taught Bartkowiak the value of rigorous testing. He thoroughly experimented with every technique he would use on an upcoming project beforehand, far beyond the traditional hair and makeup tests. He later applied this approach to some of his most expansive studio films. “I’ve shot 150,000 feet of tests on some jobs. Whole movies have been shot with less film!”

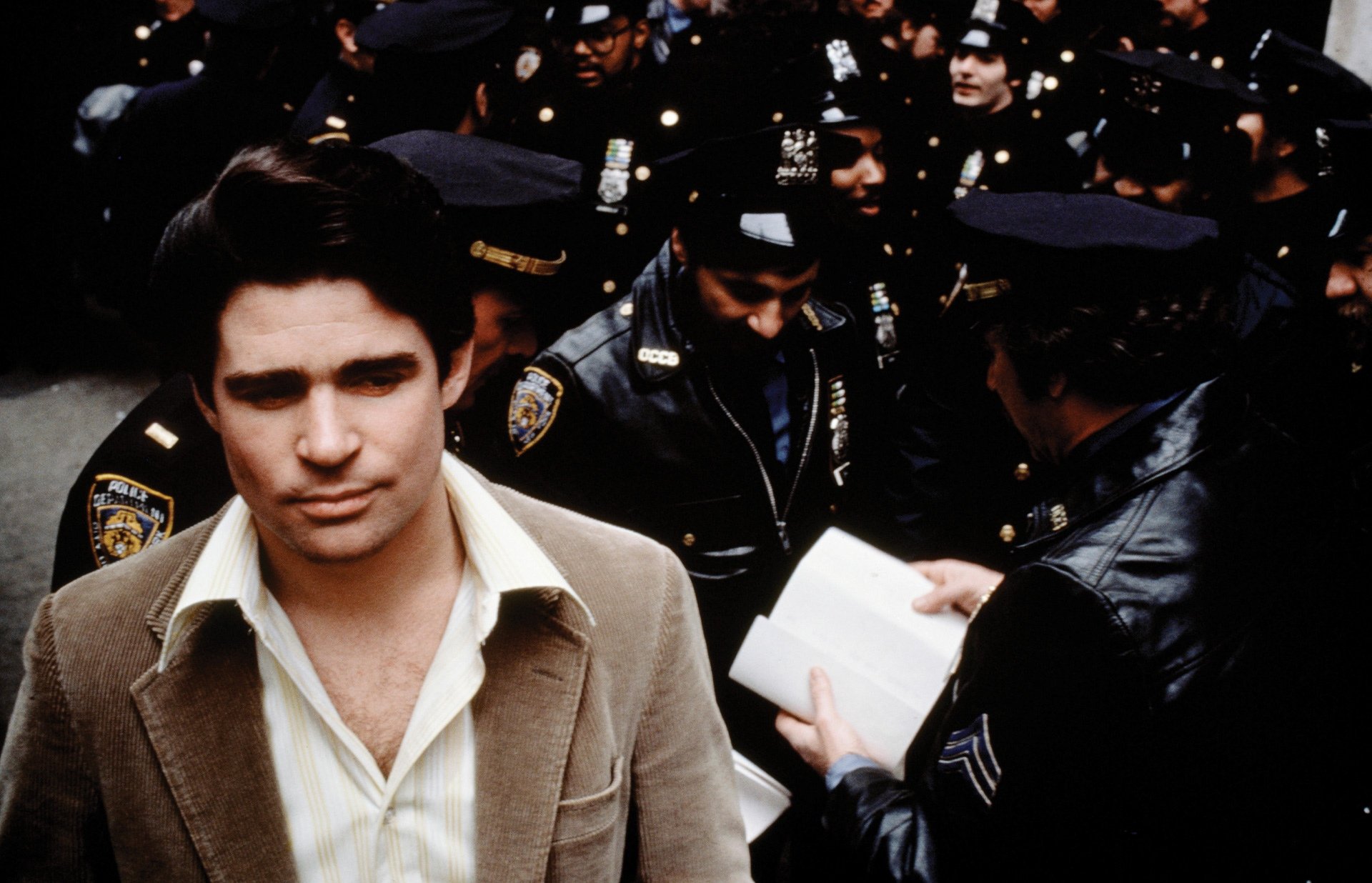

Bartkowiak notes that a strong working relationship with the production designer is critical to successful visual storytelling, and he credits Prince of the City production designer Tony Walton for his contributions to that film. “Sidney wanted the audience to feel that the whole world is closing in on Treat Williams’ character. The idea was to avoid seeing the sky in exteriors. [Scouting with Walton,] we found locations throughout New York where we could shoot without having sky in the frame. Then, for earlier parts of the story, we’d shoot a lot of masters tight with a 75mm lens to help isolate his character. As the situation closes in, we’d start using wider lenses and move even closer to the character. It helps you feel what he’s feeling, but not in an obvious way. I hate obvious! I never want to do anything that the audience will notice, because that takes them out of the story.”

Distinctive Dramas

While continuing his collaboration with Lumet on Deathtrap, Daniel, Garbo Talks, Power, The Morning After, Family Business, Q&A, A Stranger Among Us and Guilty as Sin, Bartkowiak branched out to shoot other films, including James L. Brooks’ domestic drama Terms of Endearment. The story delves into the complex relationship between a Texas widow, Aurora (Shirley MacLaine), and her daughter, Emma (Debra Winger), as well as the mother’s late-in-life romance with a former astronaut (Jack Nicholson).

The production was set to shoot on practical locations in Houston, Texas, where the story takes place, and Bartkowiak immediately recognized that the location for Aurora’s house, where many scenes are set, would not facilitate shooting with focal lengths that would flatter the actors: 50mm, 75mm and even 100mm. He discussed his concerns with production designer Polly Platt, and she subsequently knocked out the back wall of the house and added 50' platform extensions on both floors of the structure. A dancefloor allowed the camera crew to place dollies and shoot with longer lenses. “Many scenes look the way they do because of that,” he says. “Polly understood why I asked for this, and she’s the one who really made it happen.”

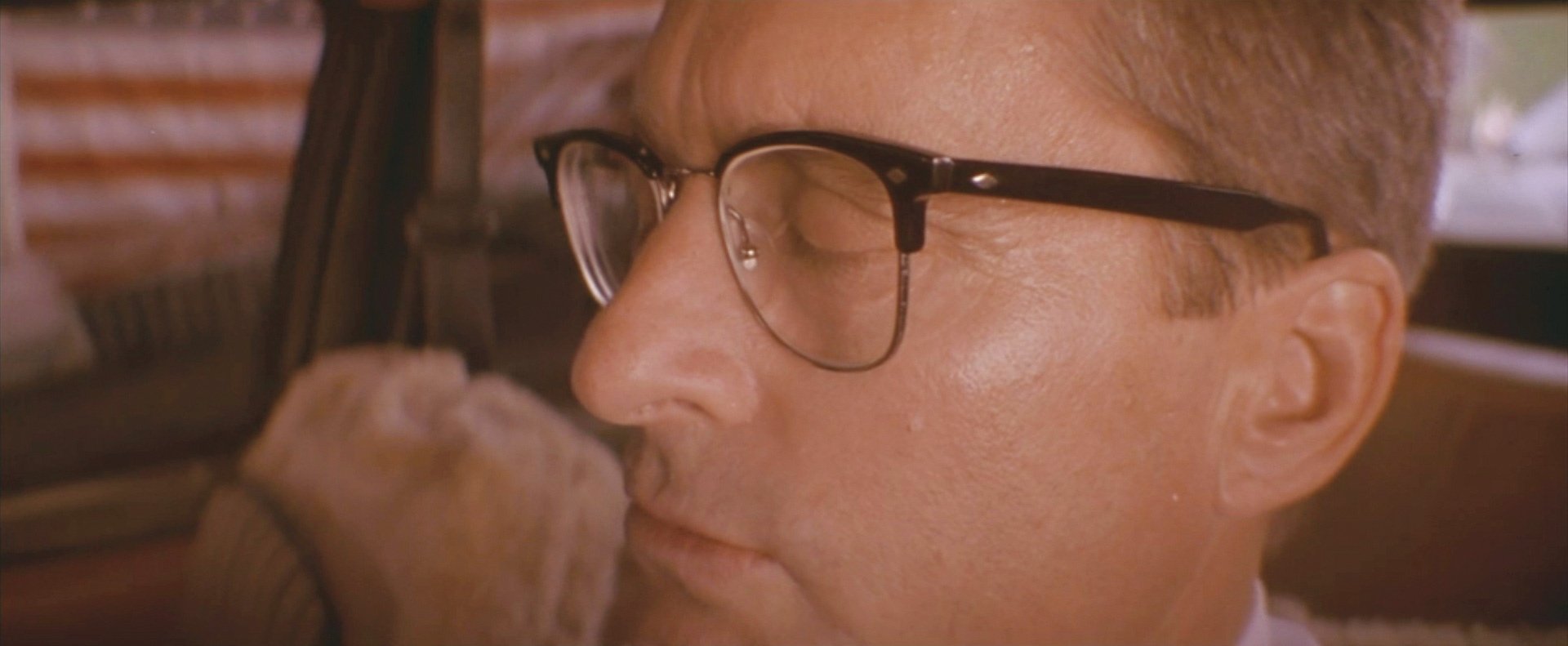

In Joel Schumacher’s Falling Down, which brought Bartkowiak a Camerimage Golden Frog nomination, a Los Angeles defense-contractor worker (Michael Douglas) embarks on a murderous frenzy after a series of personal and professional setbacks. From the opening shot, the visuals situate his world somewhere between the actual city and a veritable hellscape: Sweaty and anxious, he sits in his car under a freeway underpass, trapped in a monster traffic jam.

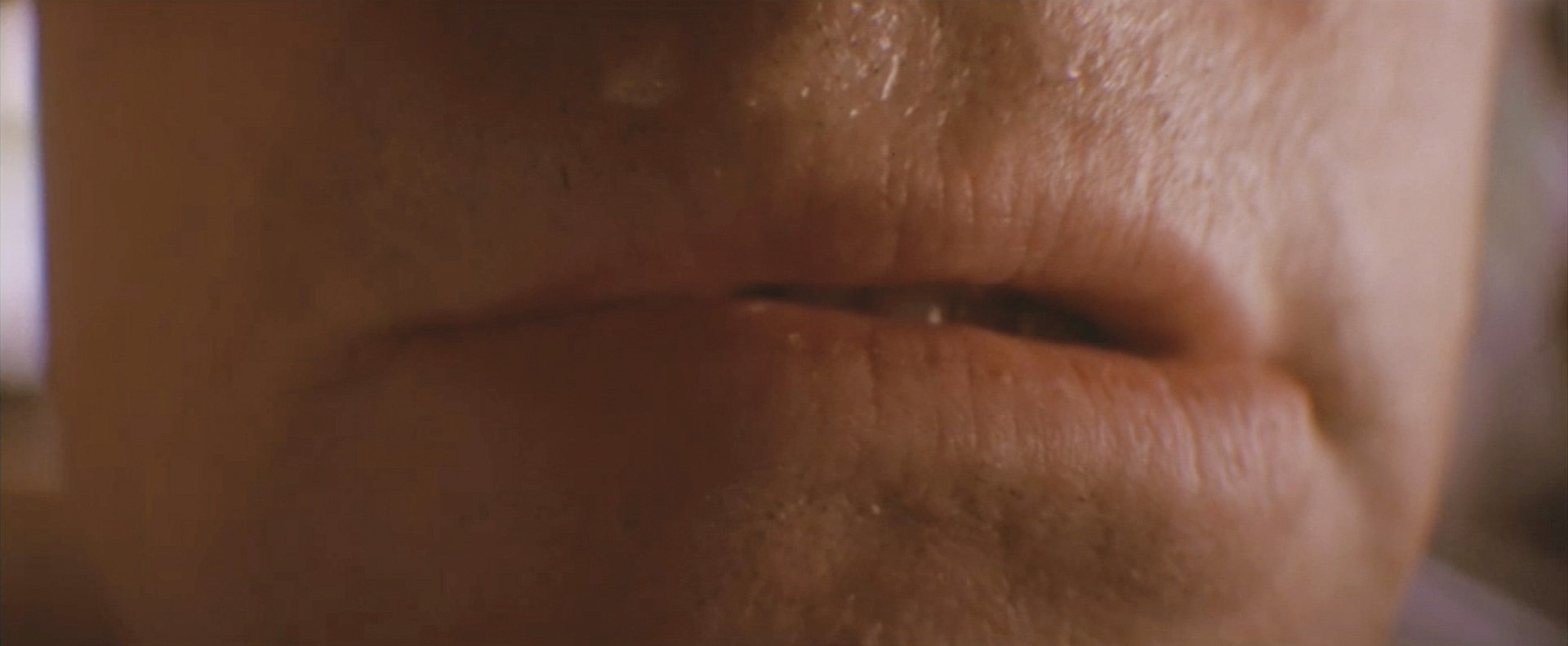

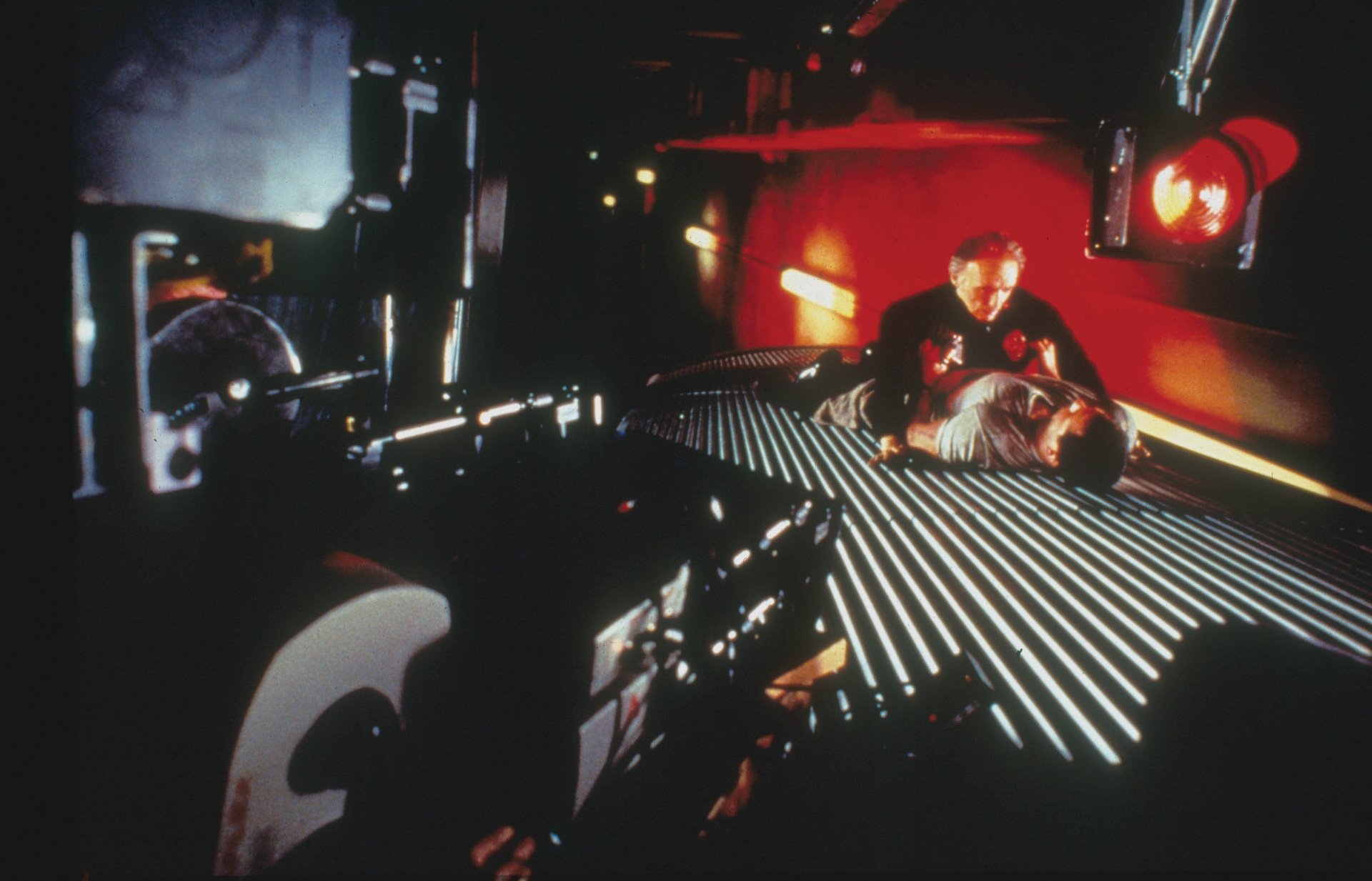

Bartkowiak actually suggested an approach to the shot in his interview with Schumacher. “I’m European, and I love great European films,” he says, noting the shot was inspired by the classic opening of Fellini’s 8½, in which Guido (Marcello Mastroianni) is trapped in a stifling traffic jam. He pitched his vision to Schumacher in minute detail, describing a single take that starts almost inside Douglas’ mouth and pulls back, out of the car, to show the surrounding cars at a standstill and then comes around to the back of Douglas’ car, ending on the back of his head. (See frame captures below.) “That’s what got me the job,” Bartkowiak recalls. “Then, of course, we had to figure out how to actually do it!”

The solution, devised largely by key grip Chris Centrella, would involve a snorkel lens, a Super Technocrane mounted onto a Titan Crane, a breakaway car roof, and a large bank of arc lights bounced from a low angle inside the underpass to bring the light level up to match the day exterior so he could shoot at T16. Additionally, throughout the film, Bartkowiak had propane heaters positioned under the lens to provide waves of heat, which he could adjust to enhance the overall sense of oppressive sweltering temperature. With these subtle distortions and near-constant use of double 85 filters, Bartkowiak’s cinematography memorably conveys the character’s addled state of mind.

Nonstop Action

The thriller Speed was the directorial debut of Jan De Bont, ASC, who entrusted Bartkowiak with cinematography duties on what would become an enormous box-office hit. “Jan was really the master of shooting with multiple cameras,” Bartkowiak says, “so thank God I had the experience I did lighting in multiple directions for Sidney! It prepared me to be able to shoot the way Jan wanted.” Perhaps it’s no surprise that someone who’d race to the set at 140 mph on his motorcycle would be attracted to the big Hollywood action films of the 1990s, before extensive CGI became the norm. “I loved it as a person — but also, I believe the results are better,” Bartkowiak says.

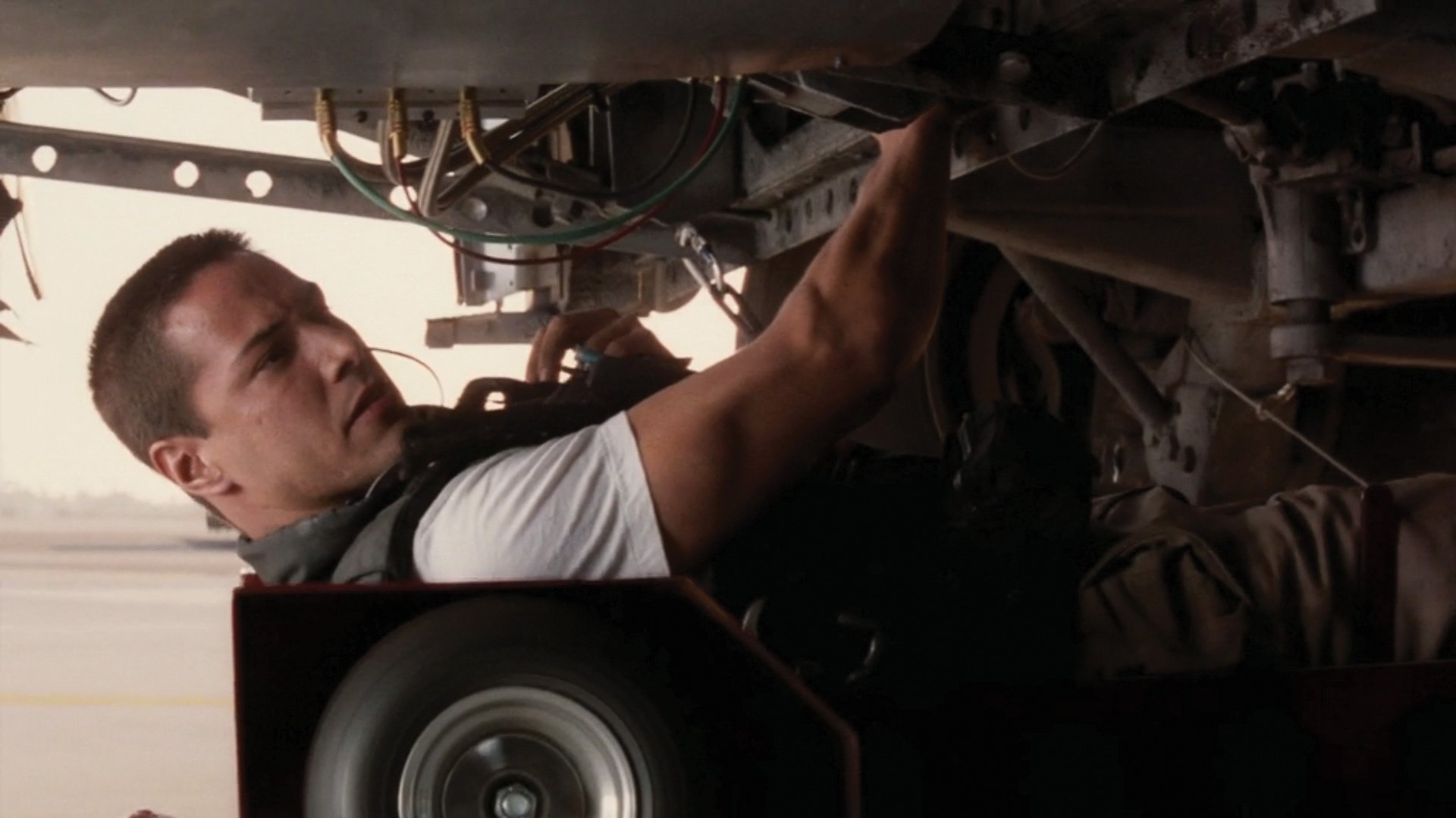

For one scene in Speed, actor Keanu Reeves slides under a speeding bus atop a simple car dolly. “Keanu really was underneath the bus, [which was driving] on an unused airport runway, and we strapped multiple camera operators underneath the bus to capture the action. Keanu was secured to the dolly, and we took a lot of precautions, of course, but it was still dangerous, and it was impossible to know if the dolly would suddenly go over debris or something. And you see that on his face! It’s not about the stunt itself; it’s about the performance.”

Donaldson’s volcano-centered disaster film Dante’s Peak featured major set pieces involving more than 27 cameras, with 1st, 2nd and 3rd units all working in tandem. An epic eruption scene featuring lead actors Pierce Brosnan and Linda Hamilton was shot in Lancaster, California, where the production built a replica of a cabin they had shot on location in Wallace, Idaho, complete with an artificial forest and lake. “It was a copy of the Idaho cabin, but it was all real, all built on location,” Bartkowiak recalls. “We were dropping magnesium bombs near the actors. Our trees were actually made of steel that was perforated with slits so we could pump them full of liquid propane to make it look like they’re on fire, with the piping also set up into the street to make it catch fire. We put the actors behind Plexiglas to protect them, but, eventually, it was too hot for them to continue. Pierce and Linda were very brave. The crew had hazmat suits and respirators, but the actors, of course, didn’t. So much of their performance is about real reactions to what was going on. I don’t think you can fake that in a studio.”

Such practical techniques require a lot of prep, he admits, but “when you see it in dailies, all that hard work pays off.”

A Seasoned Perspective

Since producer Joel Silver offered Bartkowiak the opportunity to helm the 2000 action thriller Romeo Must Die, Bartkowiak has focused on directing. The producer had faith in the cinematographer after observing him at work on his films Family Business and Lethal Weapon 4.

But one aspect of Bartkowiak’s work behind the camera remains the same: He staunchly believes filmmakers are only as good as their crews. “Anybody who says, ‘I made this movie myself,’ is full of s---. You depend on a crew every moment of every day.”

He credits gaffers Bobby V, Billy Ward, Dusty Wallace and Bobby Smith, and key grips Tom Cooney, Robert Ward and Billy Miller with teaching him an enormous amount about cinematography. “Unless someone retires or is not with us anymore, I don’t believe in change,” Bartkowiak says. “When you find good crewmembers, you keep them with you forever. I know there are some people who always like to try someone new. Sidney and I were never like that. As he used to say, ‘If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.’”