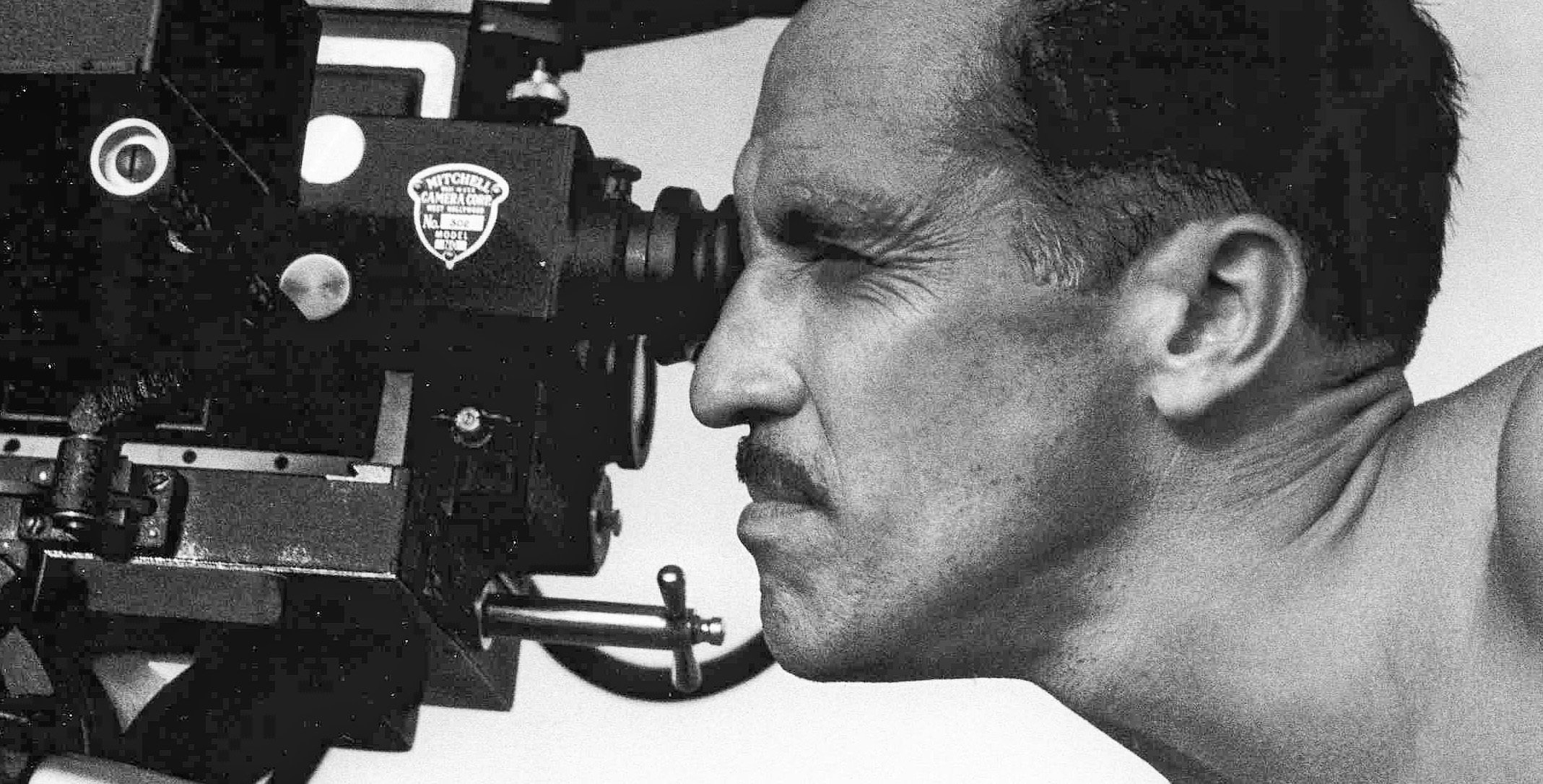

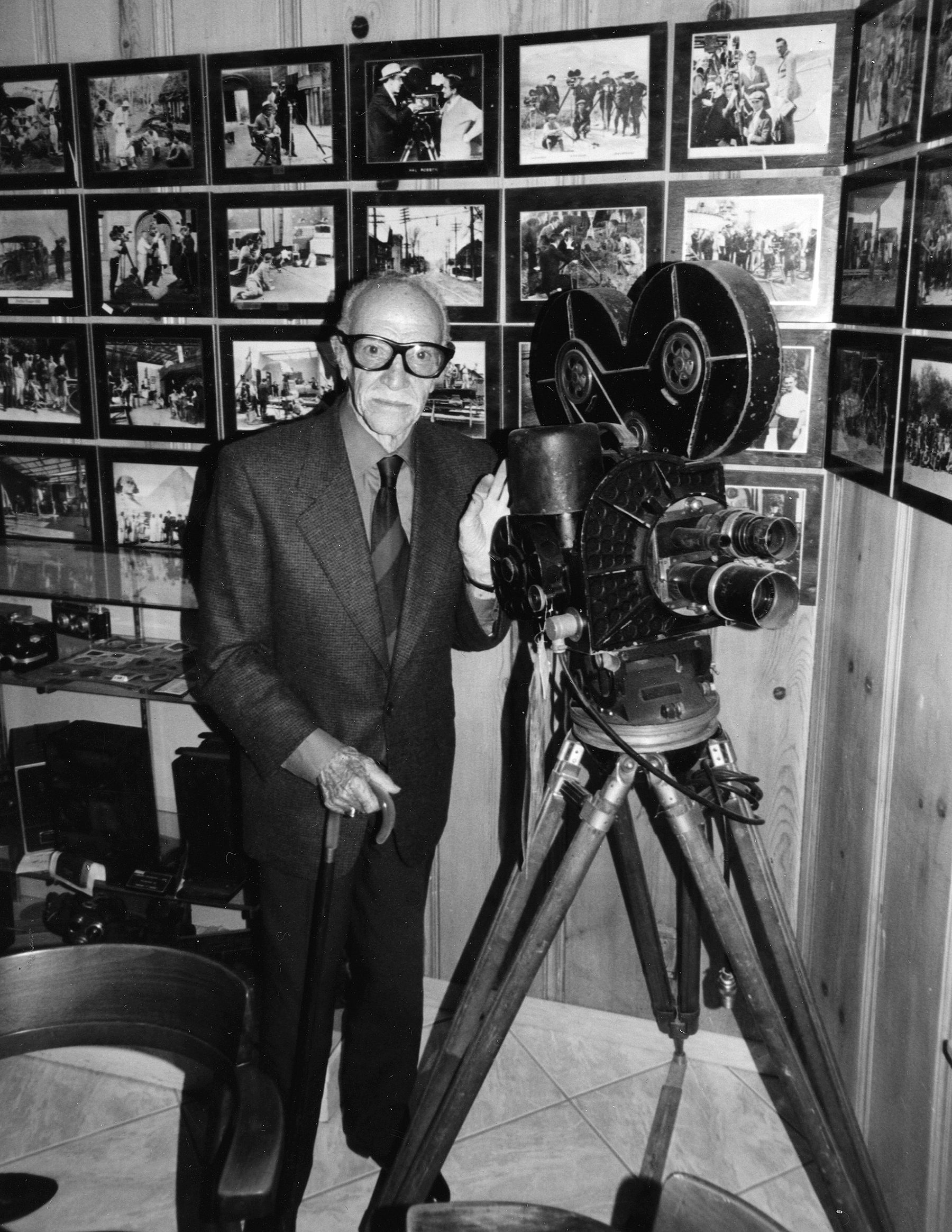

Gabriel Figueroa: Mexico’s Master Cinematographer

Combining the vibrant artistic history of his country with his own creative and technical virtuosity, the famed visualist left a lasting impression.

Editor’s Note: This profile was originally published in the March 1992 issue of AC shortly after Figueroa was honored in the U.S. by the UCLA Film and Television Archive's Mexican Cinema Project, produced in association with IMCINE and Chicanos '90.

Noted the author of his interview with the legendary cinematographer:

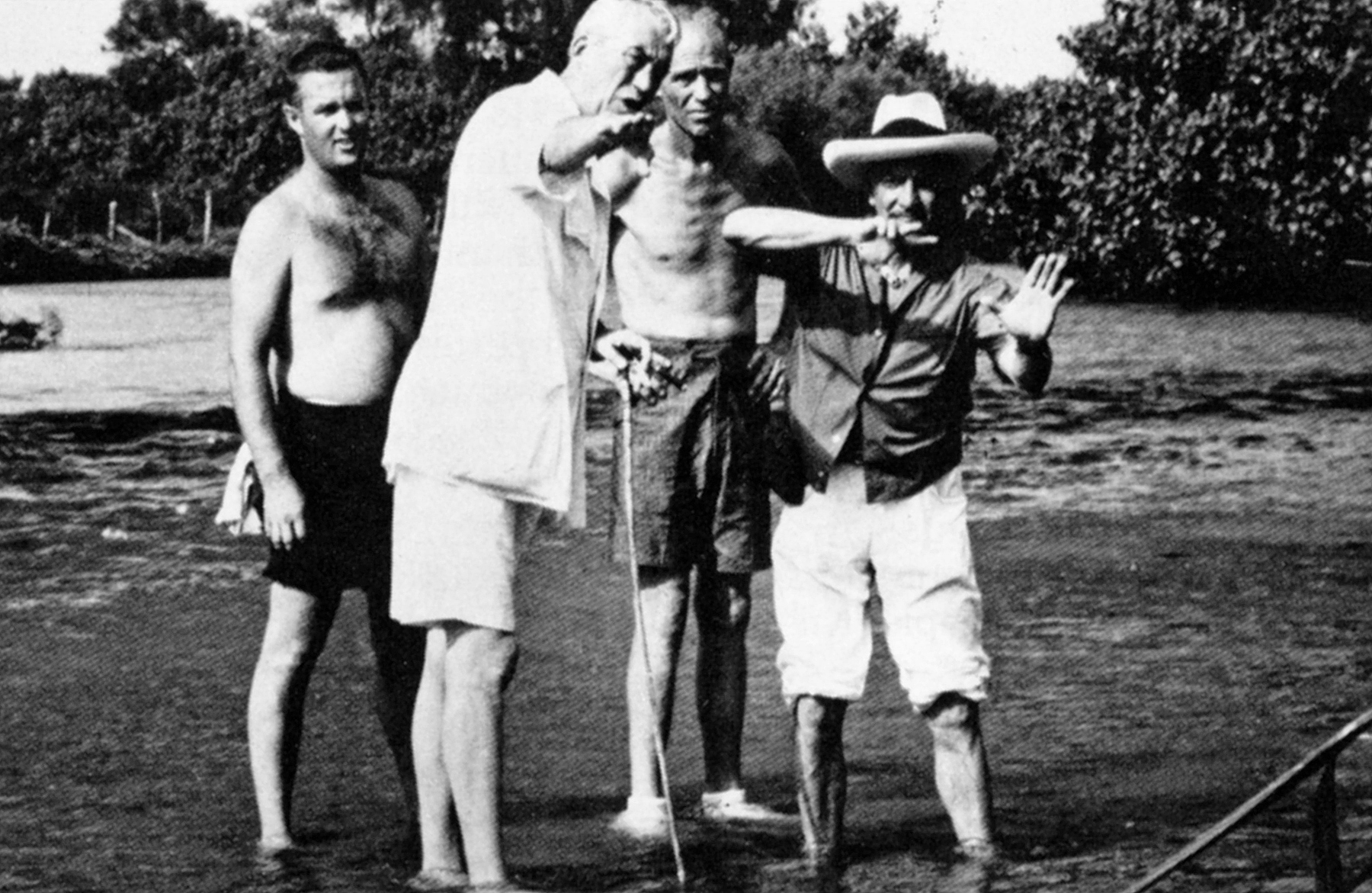

“Sitting in the study of his spacious home in Coyoacan, a quiet town with cobblestoned streets and centuries-old churches just south of Mexico City, Figueroa was anything but speechless. The slight 84-year-old took the interview by the horns, clenching his fists periodically to stress a point, never once letting his gaze wander. Speaking in Spanish over the course of two days, he told story after story, letting his coffee get cold while conjuring vivid images that leaped across time: lurking in the shadows of an MGM soundstage where he deciphered the Hollywood secrets of his mentor Gregg Toland; swimming with Tyrone Powers and Douglas Fairbanks under a hot Acapulco sun; being summoned to the very darkest corner of the Polo Lounge by Lana Turner to discuss how he was going to light her.”

Film has been described as the art form most characteristic of our century, and cinematographer Gabriel Figueroa's renowned artistic kinship with Mexican painters binds him even more strongly to that tradition. Bearing in mind his equally strong ties to American masters of cinema, an examination of Figueroa's film work draws into sharp focus the larger picture of U.S.-Mexican art history.

Born in 1907, Figueroa grew up in Mexico City, where he studied painting at the Academy of San Carlos, and violin at the National Conservatory. He and his brother were orphans, and they lived with their aunts until the family fortune ran dry. "I had to leave the Academy and go into the darkroom to make a living," he recalled. He took passport photos and pictures of girls in bathing suits and documented paintings by local artists. He entered motion pictures as a still photographer soon after the advent of sound.

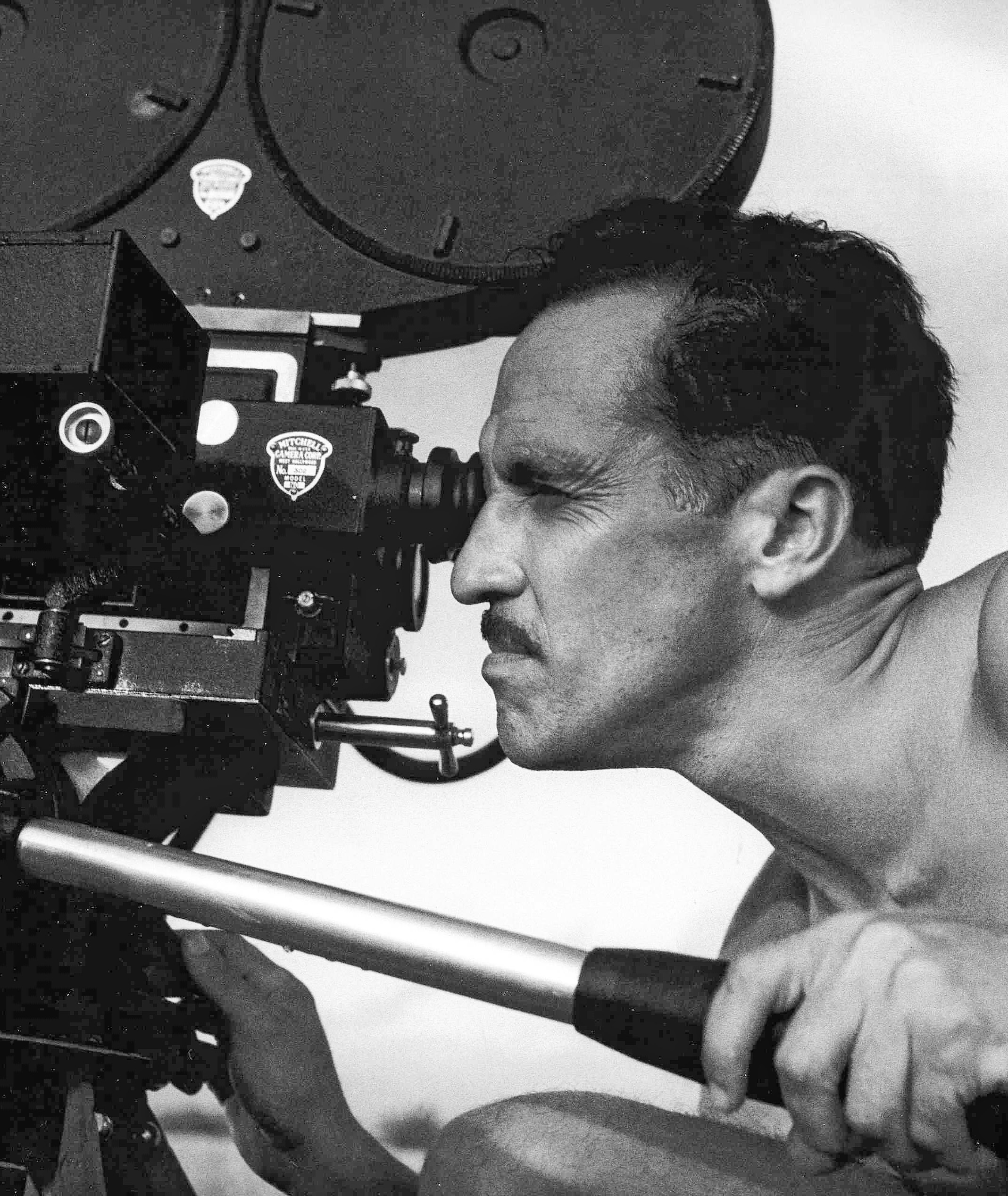

In 1933, Howard Hawks arrived in Mexico with James Wong Howe, ASC to shoot exteriors for the MGM production of Viva Villa! Figueroa, then working for expatriate cinematographer Alex Phillips, Sr., recalled the first time he got behind a movie camera: "Hawks had an assistant director who was Mexican. He called me up to tell me that they needed 20 extra cameras to help shoot a military parade for the movie. 'But there aren't 20 cameras in all of Mexico!' I told him. ‘Find one,’ he said. I finally managed to rent the only one available, a Bell & Howell 2709 with a hand crank. When I showed up for work, everyone else had batteries, but the Bell & Howell was a very good camera, and it had a better movement than the Mitchell. I later found out that cameramen in Hollywood had discovered they could maintain the proper rhythm for handcranking the camera by humming the 'Anvil Chorus' from 'II Trovatore.'"

In 1935, Figueroa was sent to Hollywood by the government-funded CLASA studio as part of a program to develop Mexican cinema. "The first person I went to see was Gregg Toland [ASC] because I had a letter of introduction to him from Alex Phillips. He was making Splendor, starring Miriam Hopkins, and I was lucky enough to have him take me on as a student. I stood on the set and watched him work through the entire picture. He told me to see [his 1935 film] Les Misérables, and when I asked him how he was able to achieve certain shadows in that film, he was pleased with my observations and revealed that they had been painted in."

Figueroa returned to Mexico the following year. In 1936, after working as an operator on three pictures for Jack Draper (another American who had relocated south of the border), he gained international recognition when his first feature, Allá en el Rancho Grande, won a prize at the 1938 Venice Film Festival and broke box-office records. From that point on, Figueroa worked steadily in Mexico, taking advantage of each free moment to go back to Hollywood to watch the cinematographers at work. "I very much enjoyed this contact with them," he recalled, "and I admired all of them immensely."

Toland continued to give Figueroa advice and critique his work. En route to Acapulco, Toland would seek him out in the studios of Mexico City and ask to see what he was working on. "Toland saw something in me I had never seen. One of the last pictures that I showed him was Maria Candelaria. He saw the strength of that picture and that's why he later recommended me to John Ford."

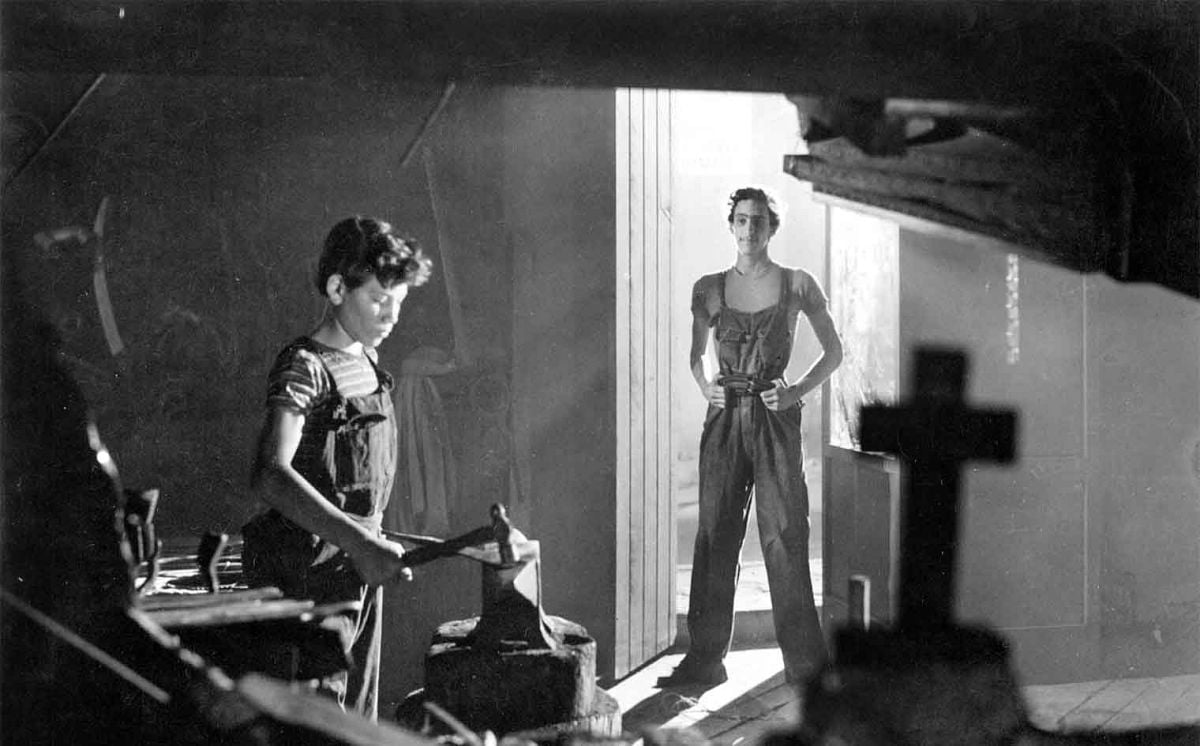

Maria Candelaria (1943) was the second in a series of classic films that Figueroa made with director Emilio "El Indio" Fernandez. The early period of their celebrated collaboration marks the beginning of Figueroa's style. "I think I have a dramatic temperament," he said. "My work has always leaned towards exterior sequences in the countryside: landscapes, mountains, rivers, the ocean."

Figueroa's allegorical interpretations of these elements, in which the sculptured features of Dolores del Rio and Pedro Armendariz figured prominently, established a truly nationalistic point of view, the likes of which had only been approached in the camera work of Eisenstein and Tisse in Que Viva Mexico! (1932) and Paul Strand in Tidal Wave(1934).

In addition to what he had learned in Hollywood, Figueroa applied the force of Mexican painting and engraving to his films. He enjoyed a free exchange of ideas with many of the artists in his country, which blurred the lines between the arts.

With muralist and friend Diego Rivera, Figueroa learned about color and composition. He credits another muralist, David Alfaro Siqueiros, with teaching him how to foreshorten his subjects, an effect he accomplished with the aid of Toland's technique of deep focus.

"The only painting I ever directly copied in my work was one by Jose Clemente Orozco," Figueroa maintained. "It was in Flor silvestre [1943], the first picture that Dolores del Rio made when she returned to Mexico from Hollywood. She invited all of her friends to the premiere and, as luck would have it, Orozco sat next to me. Well, we watched the picture, and I was waiting for the scene. When it came on the screen, he leaned forward in his chair, recognizing his work. So I grabbed his leg and said, 'Maestro, I am an honorable thief: that is from you.' To which he replied, 'But you have a perspective that I wasn't able to achieve! You must invite me to watch you work so that I can see how you obtain that perspective.' I was the only cinematographer to have such a connection with the muralists. I always found in them what I liked, and they saw my pictures, liked them and critiqued them. They said that my films were murals in movement; greater murals, because mine traveled and theirs did not."

With "Dr. Atl" — the pseudonym of painter Gerardo Murillo Cornado, known for his theories on landscapes — Figueroa explored the effects of curvilinear space. He enhanced the organic strength of his landscapes by using a 25mm lens (to which he later added a diminishing glass) that gave a slight curve to the horizon and added a feeling of movement to the sky. "All these artists inspired us to create a Mexican image for the cinema," he said. "Somehow, we found a common basis, and I was fortunate enough to see my images accepted all over the world."

Maria Candelaria won prizes for best photography at the Cannes, Venice and Madrid film festivals, where critics started talking about "the skies of Figueroa." American Cinematographer acknowledged the craftsmanship of the picture:

"Admittedly drawing on knowledge, technicians and inspiration from Hollywood, the studios south of the border are at last evolving a cinematic style embodying the technical finish of American films plus a quality of artistic approach which is particularly their own.

"The sets [of Maria Candelaria] are almost painfully simple — mostly exteriors with a few adobe huts, a church, and the water-traced foliage of the region in which it is set. These simple elements the cinematographer fashioned into a film composition that is truly poetic. The exteriors achieve a stunning realism — not of a harshly documentary type, but of a rich quality that may truthfully be called rotogravure. The result is due to the correct use of heavy filters, the capable placement of reflectors, and angles that enhance the natural pictorial quality of the backgrounds."

Figueroa revealed that his use of certain filters was inspired while studying Renaissance painting: "In a book by Leonardo da Vinci called A Treatise on Painting, da Vinci says that more important than anything is the color of the atmosphere. 'What color [is it] if we don't see anything?' I asked myself. But I began to investigate what this color was and I began to see it on the screen. I found that by using an infrared filter I was able to eliminate this 'smog' between the camera and the subject, giving me a much clearer image. They used this filter during the war to photograph at night, and it occurred to me to use it in the daytime."

During our interview, Figueroa drew an infrared filter from its ancient leather pouch: "I bought this from the Agfa distributor in Mexico City when he was called back to Germany to fight in the war. It gave me an f2 — ASA 100 — at midday in Acapulco where the sun is even stronger than here. I later bought a set of Wratten filters and combined greens with slightly lighter reds so that I could obtain the infrared effect in varying intensities. We had to paint the actors' lips brown so that they wouldn't appear white; otherwise, we didn't have any problems."

The photography of Maria Candelaria is remarkably three-dimensional. Separation of the subject and background is heightened, especially in the closeups, by the fact that the faces are brighter than the middle grey skies and darker than the white clouds against which they are framed. In an interview with Mexican historian Marguerita de Orellana, Figueroa explained that he sought to "incorporate Mexican landscape in balanced forms, chiaroscuros, half-toned skies, and the kind of immense clouds we all fear, so that the cinematography could achieve a very Mexican image through black-and-white."

As Figueroa’s prominence grew, so did his responsibility. During the labor struggles of the mid-1940s, he was called upon in the political arena. In 1944, everyone who worked in the film industry in Mexico belonged to an all-powerful union called the STIC. Soon after becoming secretary-general of a division of this union that included actors and technicians, Figueroa found himself at odds with the system: "We had a mess with the union because the people who managed the cinemas and the distribution of films were gangsters. They had control of the whole industry, which at the time was making a lot of money. They were making things very difficult, shaking down American production companies to get more money from them or making them take more workers. [The actors] Jorge Negrete, Cantinflas and I tried to break away from them by setting up our own office, and when they tried to stop us with false documents, I published a notice in the newspaper condemning the corruption in the union.

"The Central de Trabajadores Mexicanos [the umbrella organization of Mexican labor] arranged a meeting between all of the divisions of labor. When the leader of the CTM asked me to talk, I told him everything, all of the corrupt things that these men had been doing. All of the sudden, this gangster cut in: 'So, tell us names, then.'

'Well, you, sir,' I said, 'are at the head of the list.' He shot out of his seat and called me an idiot. I said, 'Don't call me an idiot,' and as I got up, he hit me; he was a big man and he wore a ring that broke my cheekbone. I went to the hospital and we left the union to form the STPC [Sindicato de Trabajadores de la Producción Cinematográfica], the union that exists today.

"In the beginning, we couldn't work. We had the people, but we needed a license from the government. The industry was paralyzed for at least a month. And then a leader of the electricians, a very honest man, decided to help us out. He called the Secretary of Labor and said, 'The people in cinema are taking big losses. Tonight, we are going to pull the power switch to the Central District of Mexico City for one minute. Tomorrow, two minutes, the day after, three, and so on until we are granted the right to work.' They turned off the electricity three nights in a row, and on the third day we received approval from the government to make our films."

The STPC took up headquarters in the Churubusco Studios, recently constructed with funds from RKO and U.S. entrepreneur Harry Wright, and soon things returned to normal. In a strange twist of fate, Figueroa was paid a visit by American director Raoul Walsh; the repercussions of their meeting followed Figueroa for the rest of his career. Figueroa explained what happened: "[The gangsters] had the license to make films but we had all of the creative talent. So they called Walsh [for personnel from the U.S.] and he came into our office at the studio with one of the STIC from Tijuana. I introduced myself to him and he said to me, 'First, I want to ask you a question. Why did you back up the strike of the laboratory workers in Hollywood?' And I told him, 'Because they are workers and we are workers, and in any part of the world I will give my hand to workers.' 'Who told you to?' So I told him how I was instructed to do so by the secretary at that time. 'Is he a communist?' Walsh asked. 'I don't know,' I replied. 'Why don't you go and ask him.' 'Are you?' he continued. 'That's none of your business.' We fought for a while and finally he left. "I've never belonged to any political party, neither here nor outside of Mexico," Figueroa concluded.

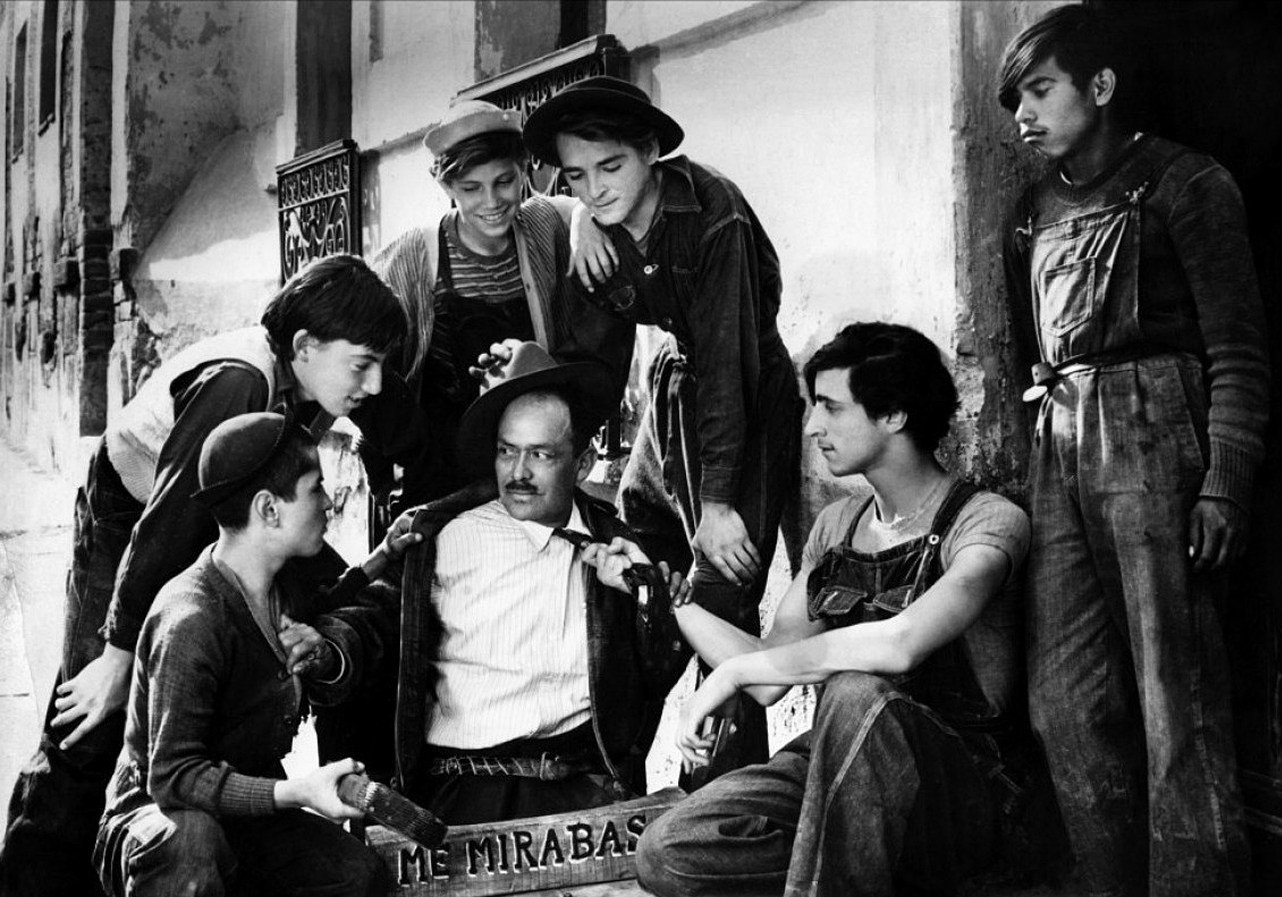

With the new freedom created by the STPC, Figueroa teamed again with director Emilio Fernandez to create another masterpiece, The Pearl (1947).

The script was written by John Steinbeck, who later turned it into his famous novella. In 1946, it earned Figueroa another prize in Venice, and, in 1948, he won the prize for Best Photography at the Hollywood Foreign Correspondents' Golden Globe Awards.

The film, similar in theme to Maria Candelaria, again paid homage to Mexico's indigenous culture, making "sculptures of the Mexican Indians and infusing their landscapes with the hieratic," according to writer Jose Maria Espinasa.

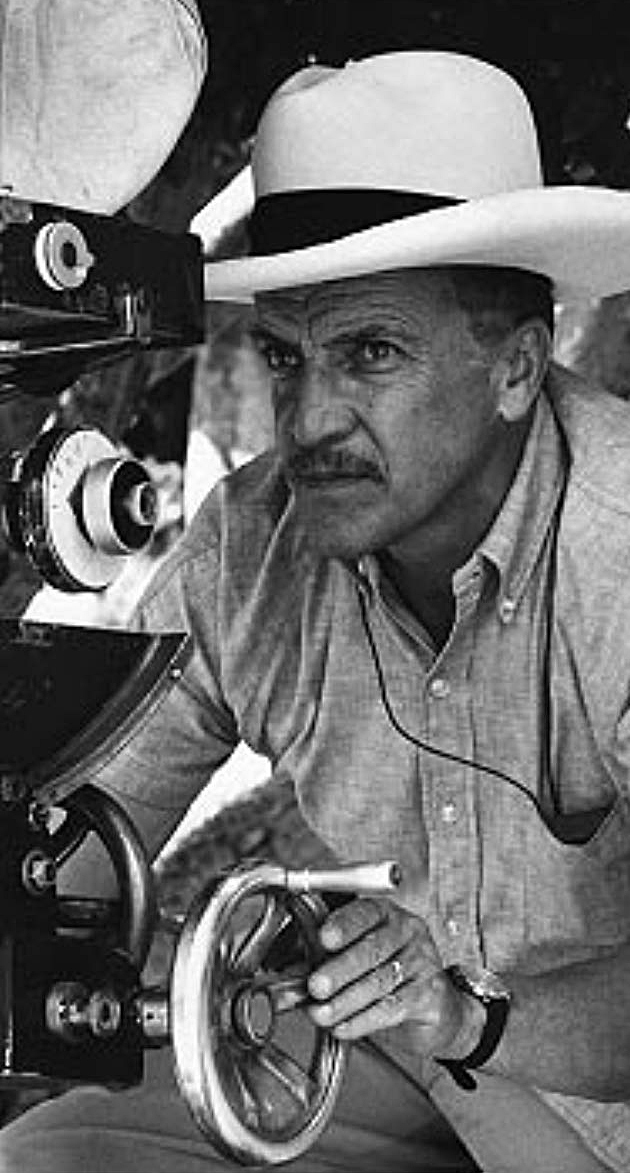

Following The Pearl, Figueroa was paid a visit by Merian C. Cooper, producer of the original King Kong. "He came into the studio one day and said, 'I want to see if I can make pictures here in Mexico.' I didn't know he was checking me out and I went about my work the usual way: when Emilio [Fernandez] asked me to put the camera up high, I would say, ‘Okay,’ and put it on the floor. That's how we decided on the angle! We were shooting Enamorada, and at the end of the day we invited him to see rushes. When the lights came on, Cooper asked me, 'How many days' work have we just seen?' 'One day and one night,' I replied. 'You're under contract!' he said. 'For what?' 'To photograph The Fugitive for John Ford.'”

Having already been asked by Toland to join his crew on The Fugitive (1947), Figueroa was surprised to learn that he would now be replacing him. Because of contract disputes with studio head Sam Goldwyn, with whom he was under contract for his entire career, Toland had to drop the film. When he apologized to Ford, the director asked him if there was anyone else who could photograph the picture with the strength of Mexican painting and engraving and Toland replied, "In Mexico there is one cameraman who is stronger than I am: Gabriel Figueroa.”

Figueroa took quickly to working with Ford: "The first day of work with Ford we went to the location and he said to me, 'We begin here tomorrow. It's day. Tabasco. There's sun. Strong. Establishing shot. Put the camera where you want.' I arrived the next morning at seven and began to light everything. When Ford arrived, I asked, 'Would you like to check out the camera angle?' He answered, 'Me? I'm only the director! But what lens do you have?' 'Forty millimeters,' I said. He replied, 'Then your frame cuts here and here.'"

Figueroa recreated the very precise gestures of the director with his hands, then threw them up in the air and said, "After 75 films I still can't tell what a lens will do! But Ford knew with tremendous precision. 'I never get behind the camera,' he said, 'nor do I see rushes. I see the faults here [on set]. I don't need to go to a projection room to see what I've done wrong.' He was as sure as that. He had a fabulous security about him. We discussed the next shot, and then for the rest of the film he let me put the camera wherever I wanted."

Released in 1947, Ford later said that The Fugitive was his favorite film, especially for its photography. He immediately offered Figueroa a three-year contract, but when they attempted to shoot their second film, this time in the U.S., Figueroa was denied working papers. "I have a letter that Toland sent to me when this happened," Figueroa revealed. "He said, 'Raoul Walsh accuses you of being a communist, but there's nothing you can do about it because McCarthyism is very strong right now, above all in Hollywood.' Ford called me up and said, 'I'm very sorry, they didn't grant you a permit. We'll cancel the contract.'

"He paid me the remaining three years of my contract," said Figueroa. "There was no other filmmaker who had a heart as big as Ford's."

With the success of The Pearl and The Fugitive, Figueroa received other propositions from Hollywood through his agent, Paul Kohner. On September 28, 1948, Toland suddenly died in his sleep, and Figueroa was offered the remainder of his contract with Sam Goldwyn: five years with another five optioned. Figueroa took three days to think about it before turning it down. "It was a great contract, the best in Hollywood. But I had my life here in Mexico, which was precious: my wife and family, my friendships with all of the artistic people. This was my world, and for that reason I could not accept the contract."

In Mexico, Figueroa also retained script approval. His ability to choose quality material was strengthened by his friendships with writers, most notably B. Traven (The Treasure of the Sierra Madre). He interpreted the written word with such insight that his images often replaced and outlasted the words in popular memory. Writer Carlos Monsaviais has said that "it falls to the cinematography of Gabriel Figueroa to endow the films with a coherence which juggles the dialogues to present a memorable and genuine sensitivity, the tragedy which survives the melodrama, the popular authenticity which the verbal expression is unable to affect. Through the cinematography, the literary essence becomes transparent."

He adds, "Figueroa's best work is what moving pictures are all about: that which we struggle to say, but for which we cannot find the words."

John Steinbeck came back to Figueroa in 1950 with Elia Kazan to show him the script of Viva Zapata. "I read it and I didn't like it, because it was a kind of Viva Villa!" Figueroa recalled. "It didn't explain what Zapata was fighting for. I was with them for three days, and on the third day I said to Steinbeck, 'John, you've made a mistake here. It doesn't show why Zapata fought. And this other scene in which there is poetry and Zapata. What? Zapata and poetry? Impossible. This scene shouldn't be in the film.' Kazan called me and said, 'You're a very brave man to argue with John Steinbeck.' 'Yes, I know that,' I said. 'But I know more about Zapata than Steinbeck does. I bet you that.'

"Kazan hired another writer and the next year they appeared with another script. It was considerably better, but I still didn't take it. They shot the film in Texas. Kazan called me one night and said, 'Joe McDonald [ASC] is the photographer on this picture. I told him to see your films and to follow your style, and he's doing it pretty well. Only there's one thing that they didn't teach him. Could you tell me how you shoot your night exteriors?' I agreed and told him to put a very light fog filter on the lens — this everybody was doing in Hollywood for night — but then I told him to underexpose the film to get the grain of the film. That opens the window of the grain of the film."

He added, "I was always experimenting; Toland had put this in my head. On Rio Escondido, I changed the lab's tonal range down toward the black hues. It's as if Aida's aria had been written in the key of G and I had it transposed into the key of C and had it sung by a bass. It's the same thing. The range was 6.5 and I changed it to 4. I had to illuminate the white shirts with sun reflectors to keep them from turning milky, but I got the most beautiful blacks you've ever seen."

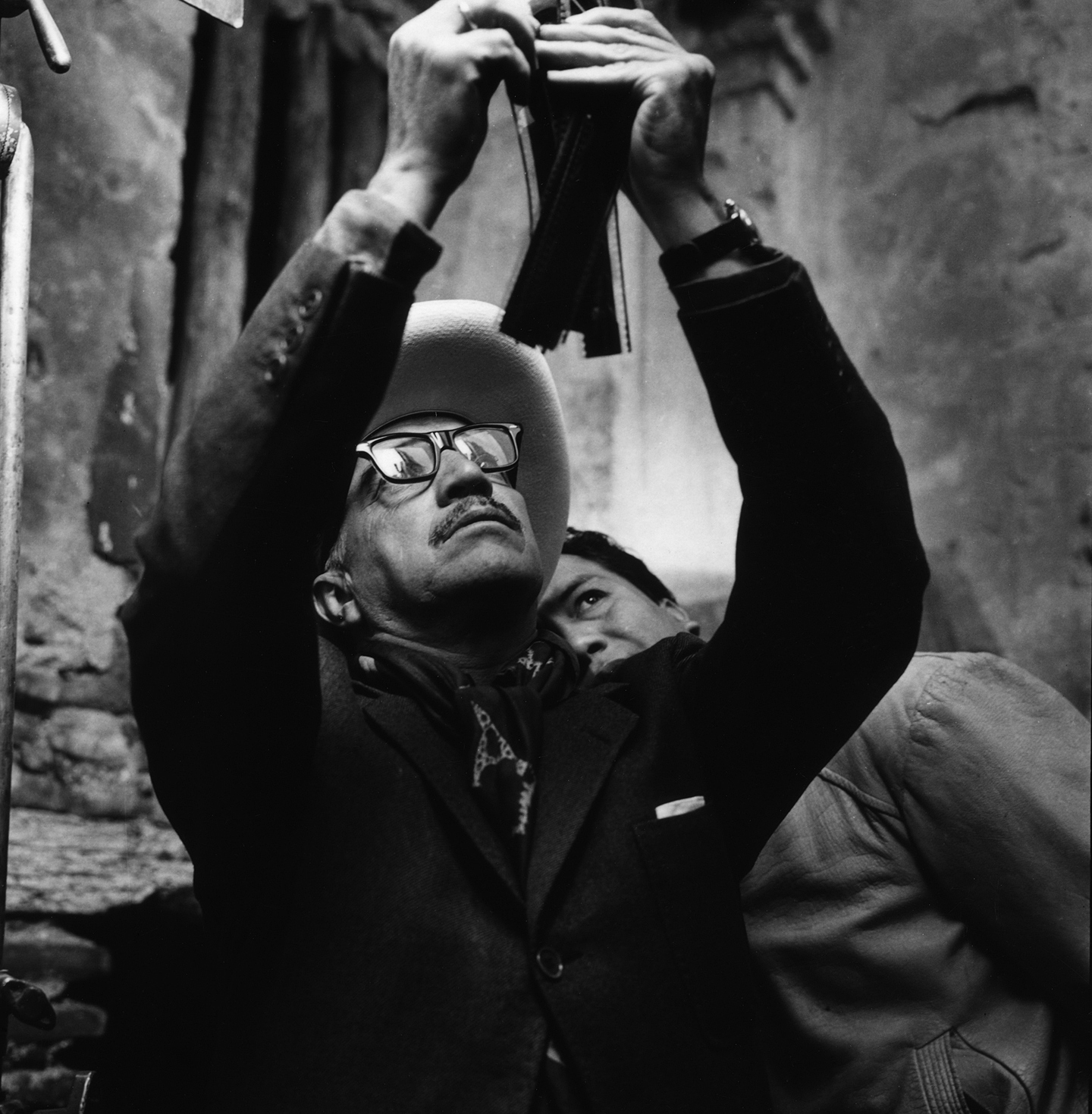

During the 1950s and early ’60s Figueroa stayed away from Hollywood and made seven films with director Luis Buñuel, among them Los Olvidados and The Exterminating Angel. Figueroa changed his style dramatically to accommodate Bunuel's sparse and sober sensibilities. "I found the trick for working with Luis," Figueroa has said. "All you have to do is plant the camera in front of a beautiful landscape with magnificent clouds and marvelous flowers, and when you're ready to shoot, he turns the camera 180 degrees and films a dirty street with dogs and people throwing rocks at each other!"

In 1964, John Huston enlisted Figueroa to shoot Tennessee Williams' Night of the Iguana. Believing that Huston worked in a manner similar to Ford's, Figueroa was surprised to find out that Huston had very specific ideas about the way he wanted the film shot. "I didn't have much input, but we became good friends and I was nominated for an Oscar. Before the ceremony, I ran into John Ford. He said to me: 'I saw Night of the Iguana, but I didn't see you in it.' He was right."

The late 1960s provided Figueroa with two opportunities to work with other American directors: Don Siegel on the western Two Mules for Sister Sarah (1970) and Brian G. Hutton on the World War II adventure Kelly's Heroes (1970) — both starring Clint Eastwood. "When I went to Hollywood to prepare for Two Mules for Sister Sarah, the head photographer at Universal said to me 'Look, don't ever go below a 4.5.' 'Anything else?' I asked him. 'No — careful with the red filters.'”

Shot largely on locations in what is today Serbia and Croatia, "Kelly's Heroes was more than 60 percent night-for-night. To give me the exposure I needed for the battle scenes I came up with an idea to simulate lightning and mortar bursts. The design was based on the old flash [powder units] used for stills. I asked my key grip to build me a compressor with a gas flame above it and fill it with magnesium. When the magnesium was forced upwards, it exploded, giving me a 4.5 — 100 ASA — at 40 yards. We lined up three of these, 25 meters apart, and when I gave word, they exploded in unison, giving off a tremendous amount of light."

Figueroa shot his most recent film in 1983, teaming again with John Huston on Under the Volcano. "The film was miscast, and the Steadicam made it impossible for me to check my framing. But Huston liked it. He asked me to shoot his next film, Prizzi's Honor, but I was again denied working papers."

Though he never officially retired, Figueroa stopped making films in 1986 by default. "The scripts I was offered didn't interest me," he said. 'I was asked to do Rambo: First Blood Part II — it was shot in Mexico — but I turned it down."

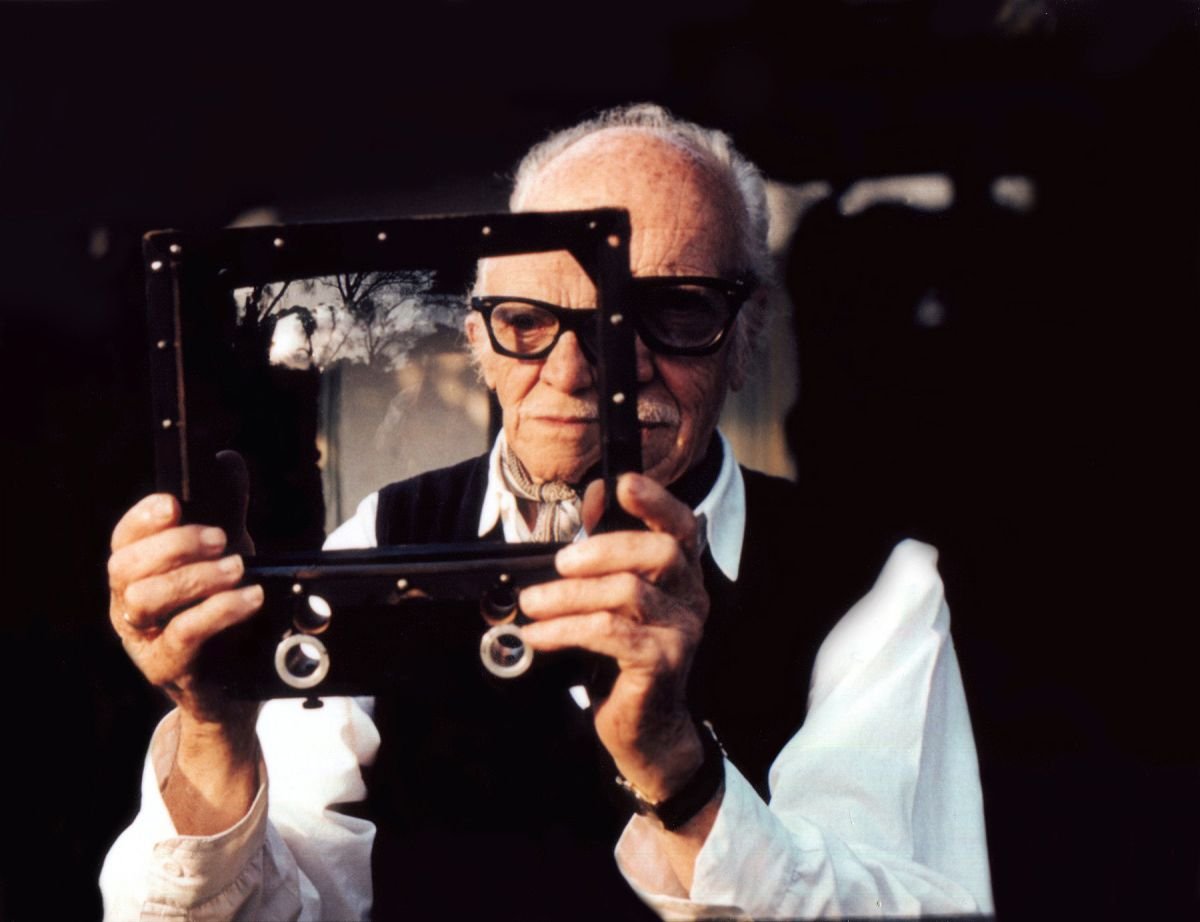

Figueroa instead spent most of his time with his family, making occasional honorary appearances at film festivals around the world. His work continued to influence and inspire viewers, and his images remain part of the common memory. Nobel Prize-winning author Carlos Fuentes said of Figueroa's Mexico:

"The beauty is there, it is real, but Figueroa magnifies it, giving it space to ponder itself, deform itself, perhaps even to get lost in itself. What's more is that the beauty of Figueroa's images doesn't only hide the will of the craftsman but stresses an unwillingness to reflect reality. Instead of adding these images to the world, he hands them back with a life of their own: not just an impossible duplicate copy. The actual reality on which his images are based will one day cease to be real… and then the metamorphoses of art will become the true reality: we'll see Figueroa's Mexico and not the one that really existed. Truth is always warring with facts like these."

While being interviewed in his home for this profile, Figueroa stopped to point out some of his treasures: paintings by well-known Mexican artists such as Rivera and Tamayo, alongside those by his wife, Antonieta; silk-screened prints that his photographer son had made from some of the 4,000 light tests Figueroa had saved; a discreet nude of Dolores del Rio hanging above a hidden bar — all pieces of a world endowed by one man's vision.

Figueroa was awarded the Premio Nacional de Artes in 1977, the highest honor in Mexican arts. In his acceptance speech, he stated: "By transfiguring reality with a camera, reality transfigured me, and made me grow as a man among men. I am certain that if I have any merit, it is knowing how to make use of my eyes, which guide the camera in its task of capturing not only colors, lights and shadows, but the movement of life itself."

In 1991, Figueroa was honored by a tribute from the UCLA Film and Television Archive’s Mexican Cinema Project, produced in association with IMCINE and Chicanos '90. Among the many distinguished stars, collaborators and friends who honored Figueroa was fellow director of photography Stanley Cortez, ASC.

"I am delighted to be here and pay my respects to Gaby," Cortez said. "Tonight's tribute to a very fine gentleman and talented cinematographer is well-deserved. It is also in my view a tribute to my other good friend, Emilio Fernandez. Their enormous contributions established Mexico as a vital new force and influence in the cinema world. I first met Gabriel through my colleague Gregg Toland, who often discussed with me the extraordinary potential of amigo Gabriel — and how right Gregg was! On behalf of the American Society of Cinematographers, and myself, congratulations, Gaby. We salute you and we love you."

In 1995, Figueroa received another well-deserved honor: the ASC International Achievement Award. The only previous recipients were English cinematographers Freddie Young, BSC and Jack Cardiff, BSC. Said Figueroa: "It is a privilege to be in the company of such great cinematographers as Freddie Young and Jack Cardiff. This is the greatest honor I have received."

A graduate of the AFI, author Tom Dey would later direct such feature films as Shanghai Noon, Showtime and Marmaduke.

To learn much more about Figueroa, visit the site of the Gabriel Figueroa Estate here.