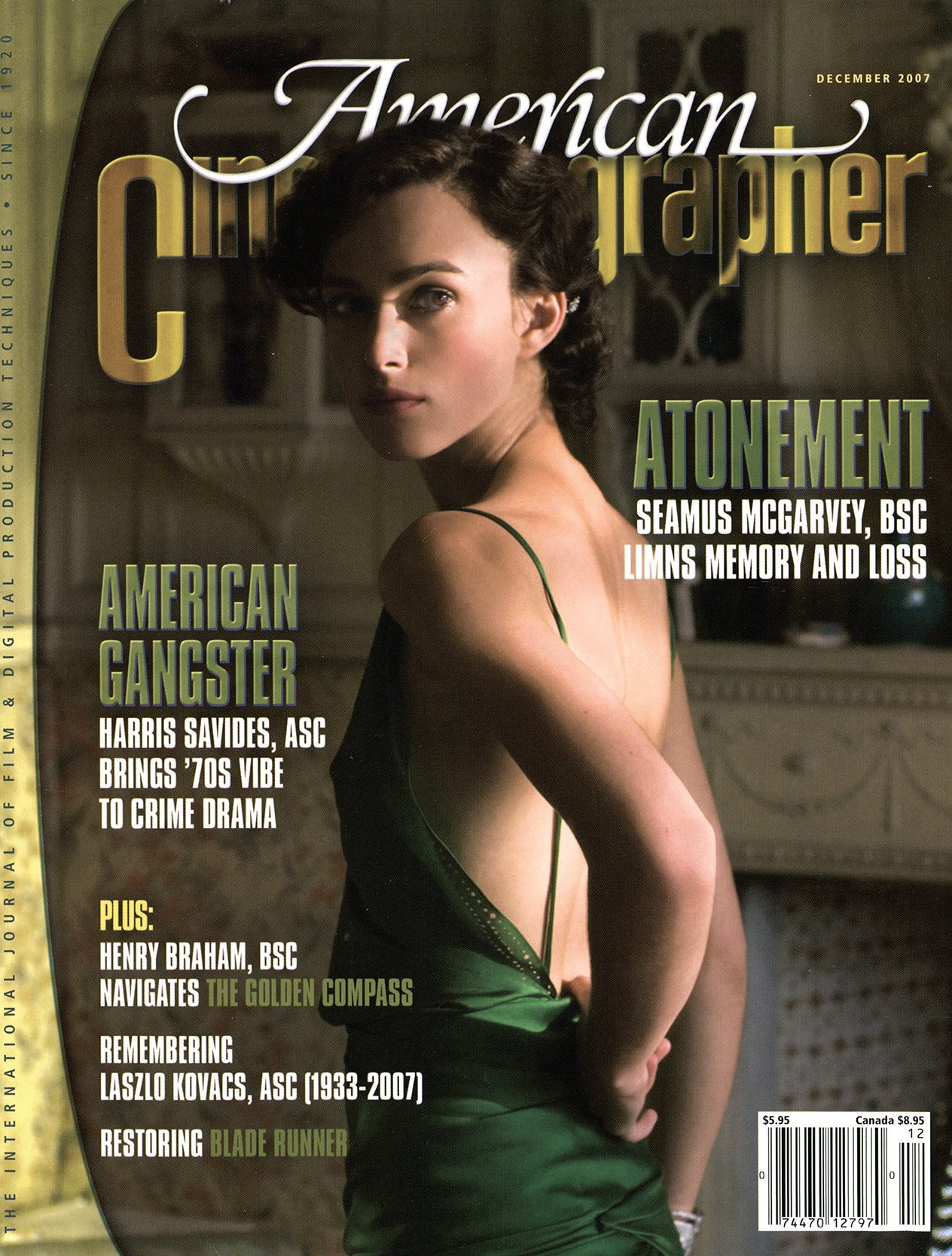

László Kovács, ASC: Promise Fulfilled

The cinematographer left a memorable legacy of movies and enthusiastically shared his hard-earned wisdom with students.

Introduction by Stephen Pizzello

Interviews by Bob Fisher, Jean Oppenheimer and Fred Schruers (except where noted)

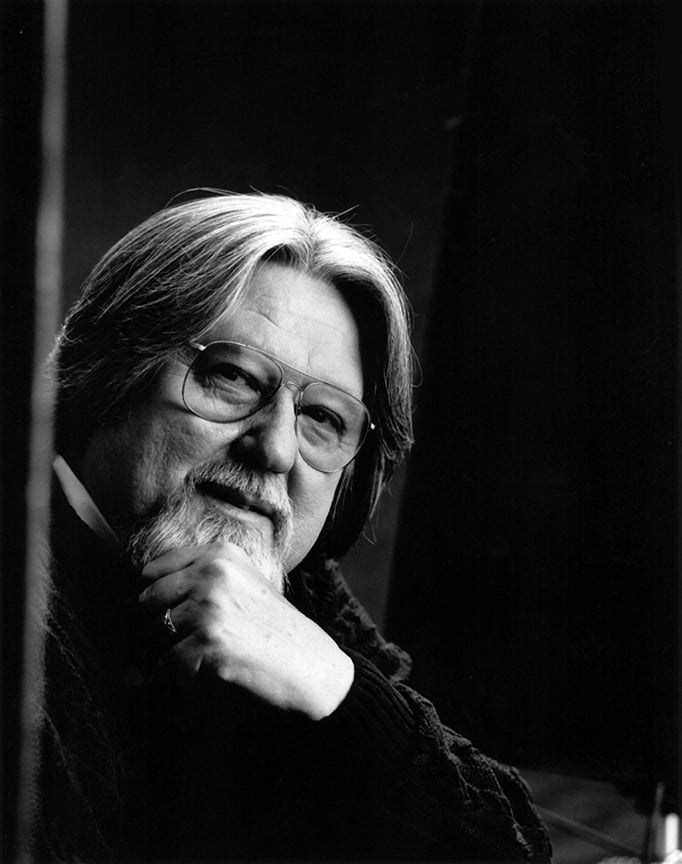

The American Society of Cinematographers lost a favorite son on July 22, 2007, when László Kovács, ASC died in his Beverly Hills home at the age of 74.

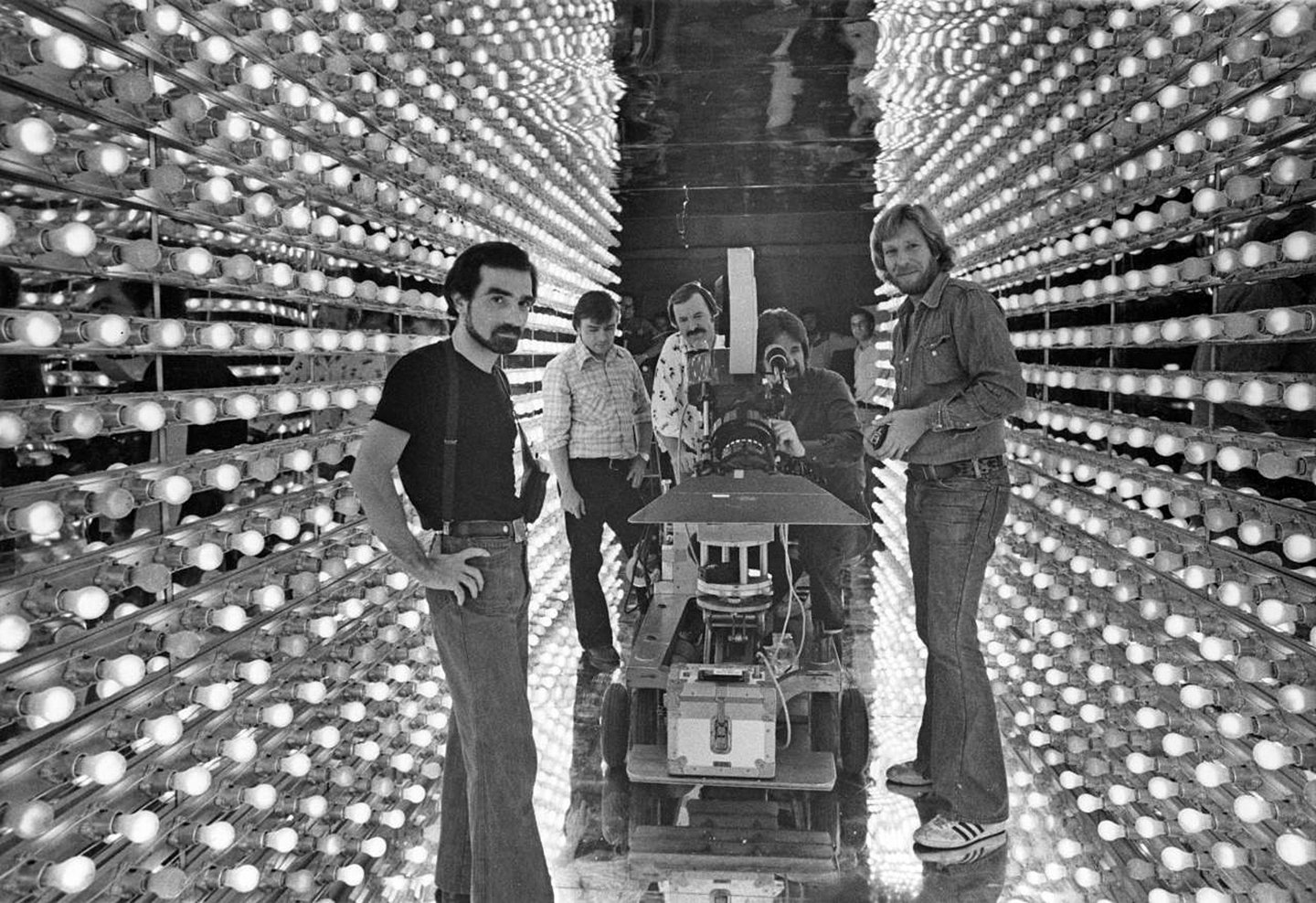

Kovács was most famous for the freewheeling camerawork he brought to the 1969 counterculture classic Easy Rider, but his résumé boasts a long string of significant pictures in a variety of genres: Five Easy Pieces; What’s Up, Doc?; The King of Marvin Gardens; Paper Moon; Shampoo; New York, New York; Frances; Ghostbusters; Mask; Say Anything ... and My Best Friend’s Wedding. He was honored with two lifetime achievement awards, from Camerimage in 1998 and from the ASC in 2002.

Kovács was born on May 14, 1933, in the Hungarian farming village of Cece, roughly 60 miles west of Budapest. In 1945, he was accepted into the Academy of Drama and Film Art in Budapest, where he and other students were dazzled by Western films that were screened secretly for them by professors. “Gyorgy Illes never allowed us to touch a camera during the first year at school,” Kovács recalled in a Moviemaker interview with Bob Fisher. “Instead, we drew charcoal portraits and learned about shapes, light, darkness, tones and textures. We also studied music, literature, architecture, painting and the history of art …. Later, he encouraged us to watch films from Western countries that were in the archives on weekends, when no Communist officials were around. Citizen Kane was my introduction to Gregg Toland [ASC]. We were told to study his lighting and camerawork and ignore the story. It was like watching a miracle happen. His lighting changed my visual vocabulary. Gyorgy Illes was a great filmmaker who was like another father to me. I once asked him how we could ever repay him for his many kindnesses, and he said I should help young filmmakers whenever I had the opportunity. I have tried my best to do that.”

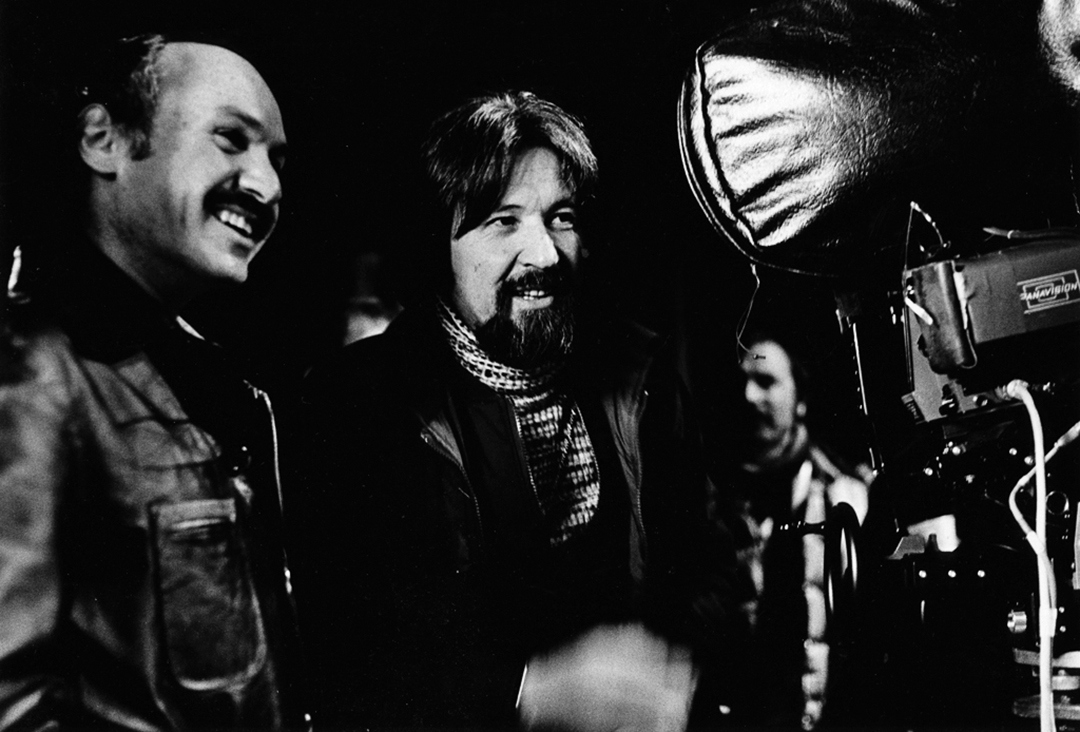

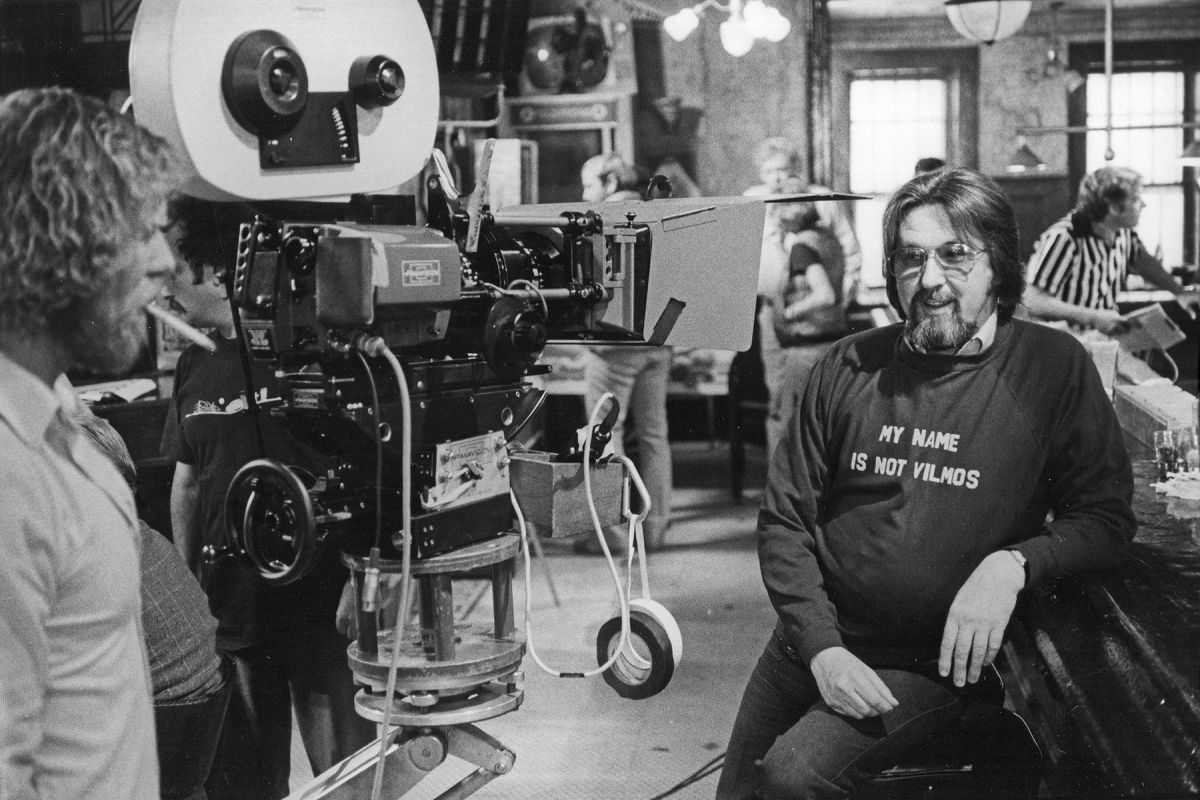

Indeed, Kovács repaid his mentor by serving for years as chair of the ASC’s Education Committee, acting as a tireless liaison between the Society and students eager to learn the art of cinematography. Along with fellow Hungarian Vilmos Zsigmond, ASC, his friend of 55 years, Kovacs also shared his wisdom by teaching a series of master classes in Budapest. Speaking for the students of the 2003 session, LuLu de Hillerin recalled Kovács’ generosity, noting, “Surely it is a mark of true greatness when one who has achieved so much has the patience and the long memory of his own youth, and takes the time to pass on his experience and wisdom to younger people who will follow him. It is a measure of László’s great love for the art he practiced so well that he took such a keen, selfless interest in ensuring its future.”

Kovács’ ride to Hollywood was anything but easy. In 1956, during an uprising against Hungary’s Communist regime, he and Zsigmond risked their lives to shoot footage of the chaotic events. After they smuggled the film out of the country, portions of the footage were later used in a documentary.

Kovács moved to the U.S. in 1957, despite the fact that he spoke no English. After settling briefly in New Jersey, he moved to Seattle. In 1959, he boarded a bus to Los Angeles, where he reunited with Zsigmond. During the 1960s, the duo honed their skills on a string of low-budget exploitation films, many of which were produced by B-movie king Roger Corman. Methods favored by the old Hollywood system were giving way to more experimental aesthetics, allowing Kovács and Zsigmond to work with smaller crews and lighter equipment while developing their ingenuity on the fly. “Those early years of no- and low-budget filmmaking gave us incredible opportunities to try different things with a minimum of equipment, slow film and slow lenses,” Kovács told AC (Feb. ’02). “It forced us to be very inventive. It was our training ground.”

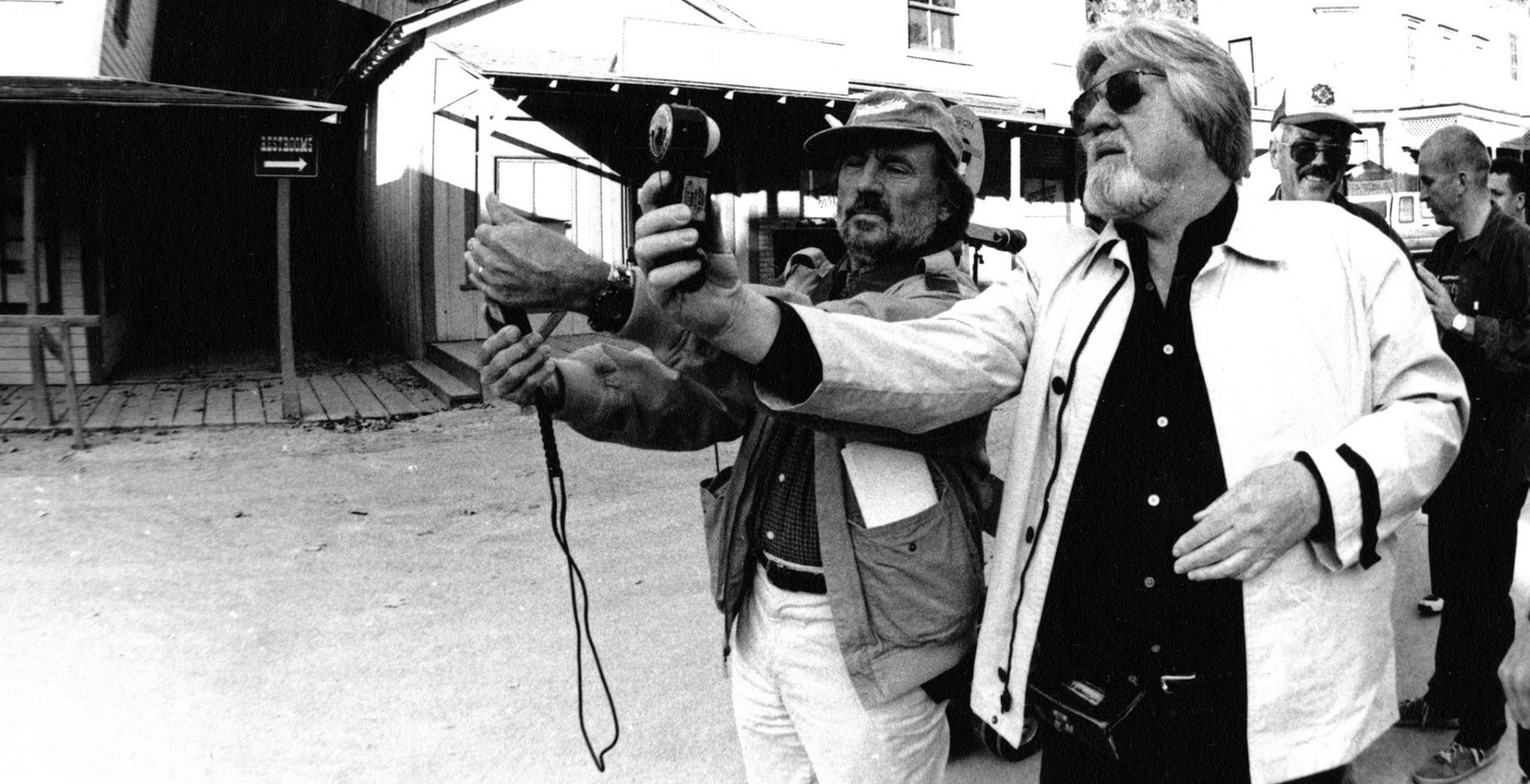

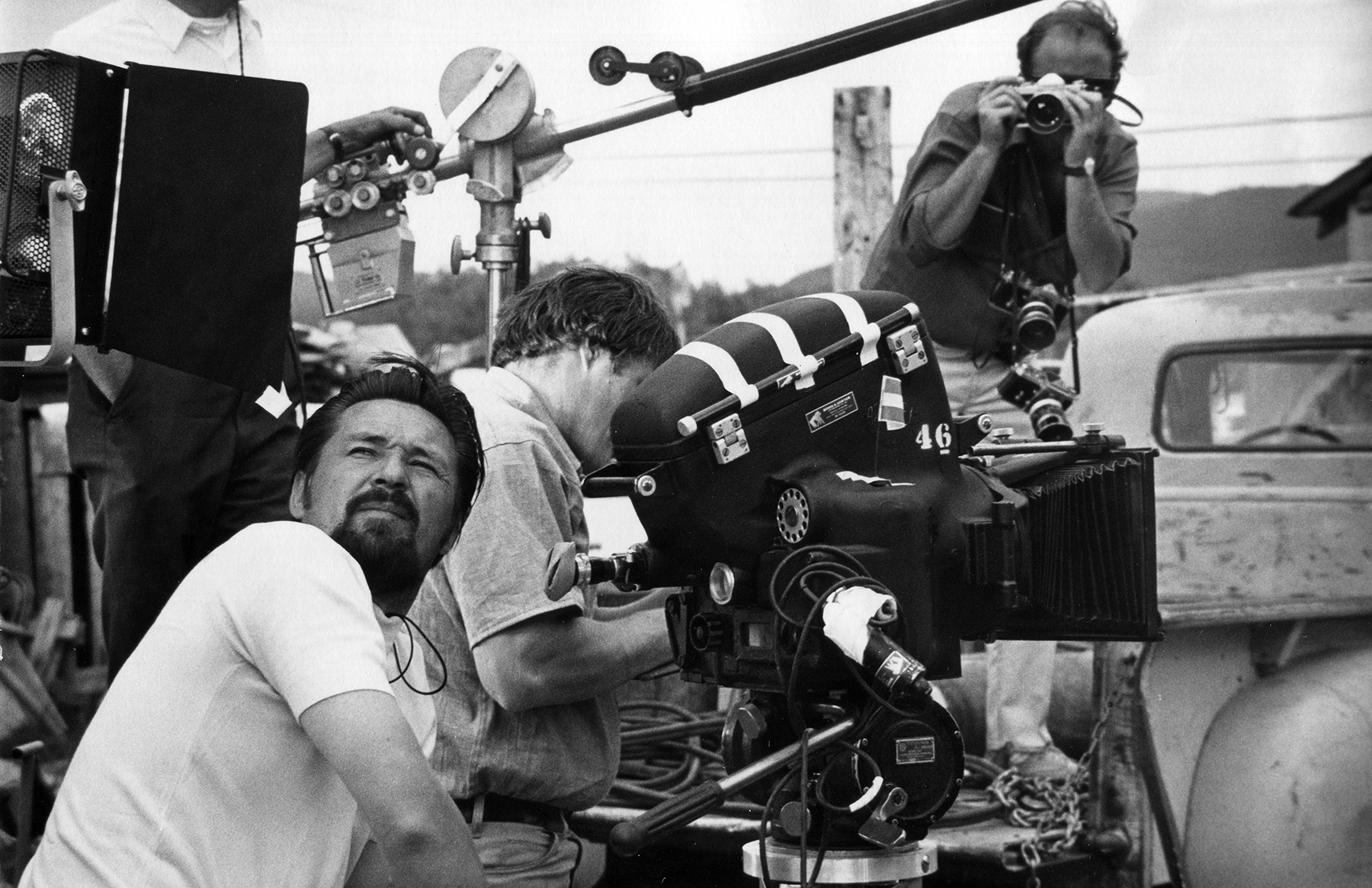

Kovács put his early experiences to great use on Easy Rider (1969), which showcased his considerable skill as a camera operator. He became renowned as one of the finest handheld shooters, demonstrating time and again his unerring eye for improvisational compositions rich with emotional subtext. He also became adept at filming with a zoom lens from a moving vehicle, a skill that lent dynamic energy to Easy Rider’s motorcycle sequences and left a lasting impression on director Dennis Hopper. “László is the greatest telephoto lens operator in the world,” Hopper told AC. “All of the shots using the telephoto on the rides are pure Laszlo magic.”

“He will be with us forever through his films and our collective memory. God bless László Kovács!”

— Dennis Hopper

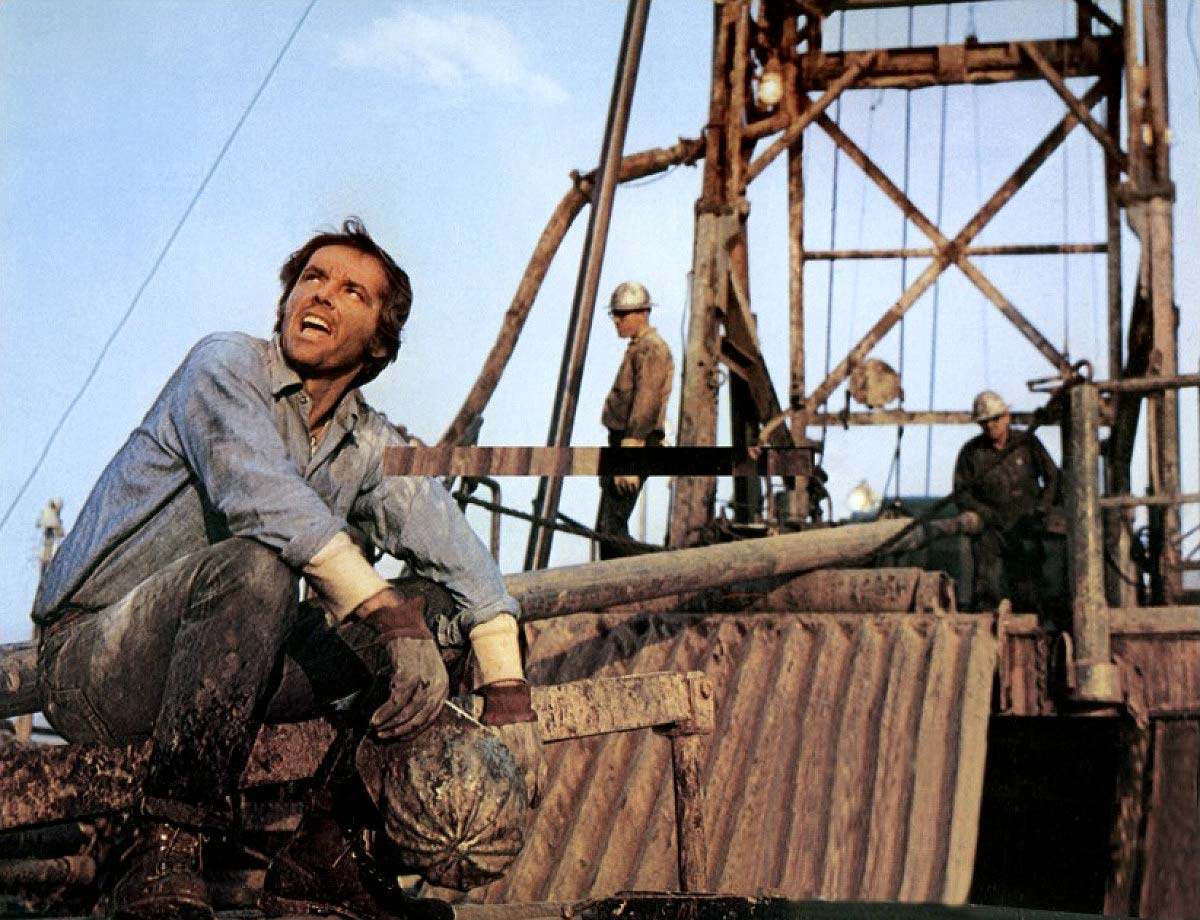

Kovács lent similar grace notes to many other films. In Five Easy Pieces, directed by Bob Rafelson, he captured a masterful pan that sums up the movie’s theme of untapped potential and broken relationships. The shot begins on the hands of once-promising pianist Bobby Dupea (Jack Nicholson) as he plays a tune for a female admirer (Susan Anspach) in his father’s home. “That shot gives the illusion of a 360-degree pan, which it wasn’t — it was really only 180 degrees,” Kovács told AC (Jan. ’05). We start on Jack’s hands so we know that he’s playing, and then pan up slowly to his face. Jack didn’t play the piano — he learned about five different chords — and that was the signal for me to start leaving his hands and come up to his face. I then moved to Susan’s hand tapping the rhythm, and then up to her face — [we shot her as an] idealized, backlit, gorgeous woman. After that, the camera just keeps going and discovers the wall, and there you see photographs of the family. As the piano music continues, we show the whole history of these people in the pictures, [which] beautifully establishes their relationships.”

This kind of cinematic thinking served Kovács well over the course of his career, during which he demonstrated not only virtuosity and versatility, but also affability and a keen understanding of people. Summing up his importance, Marek Zydowicz, founder and director of Camerimage, offers, “Even during the Cold War, student filmmakers in Eastern Europe followed László’s work and hoped they would someday be able to follow in his footsteps. He was a source of inspiration for students and young filmmakers everywhere in the world. His life proved that with talent and determination, anything is possible.”

A memorial for Kovács was held in August of 2007 at a packed ASC Clubhouse, where many friends and collaborators paid tribute to his skill, warmth and savoir-faire. Finding solace in this familial embrace were Kovács’ wife, Audrey, and his daughters, Julianna and Nadia.

On Oct. 15, a Kovács tribute was hosted by Hungary’s Los Angeles Consulate General at Raleigh Studios in Hollywood, where the consul general, Balåzs Bokor, said, “László gave an example to all of us: how to preserve his original Hungarian identity and still be of service to his new homeland. We have an obligation to keep the memory of this great Hungarian-American alive, to pay a continuous tribute to him, to his life achievement. We are proud of him and [must] contribute to raising László Kovács’ flag high.”

Following are reminiscences and observations from some of Kovács’ collaborators and colleagues.

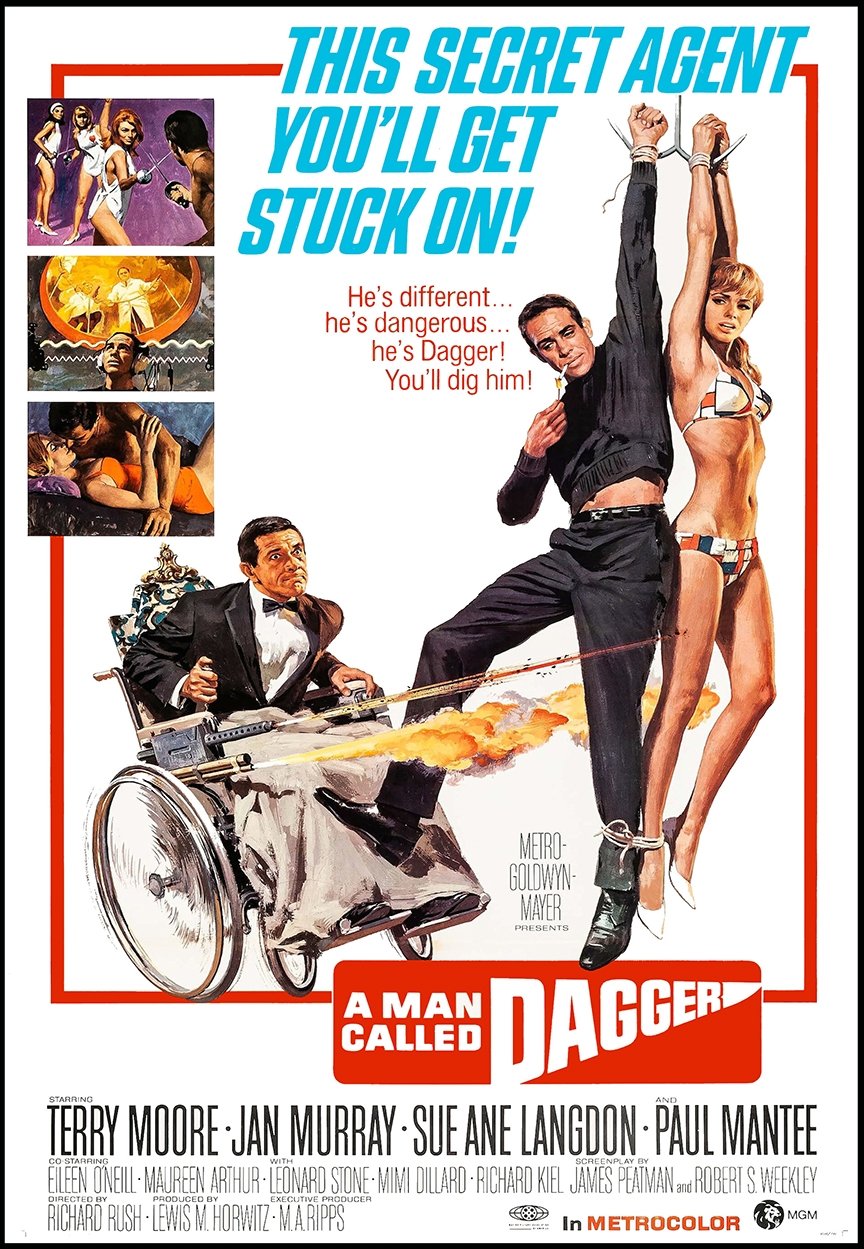

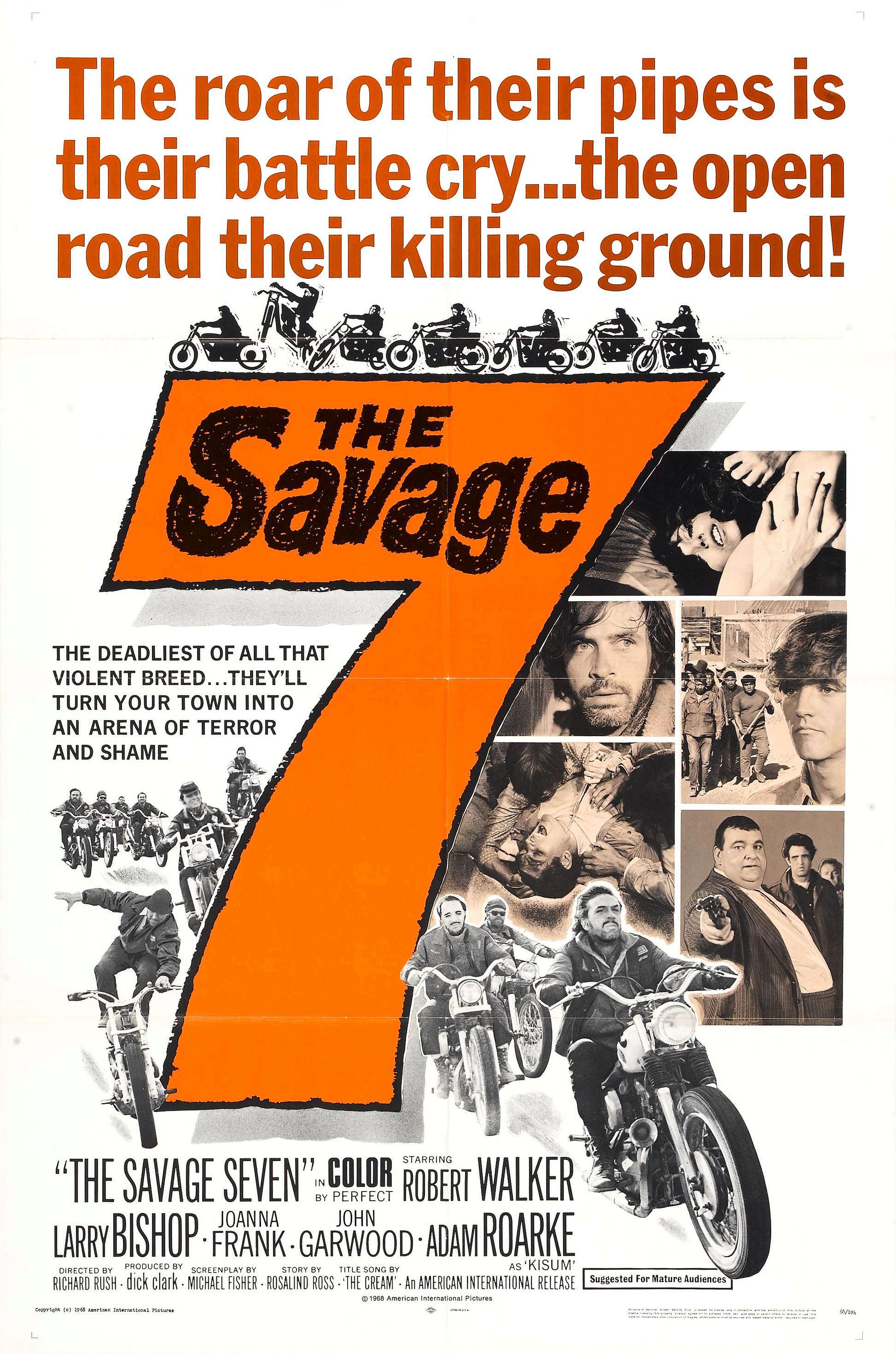

Gaffer Richmond “Aggie” Aguilar, who worked with Kovács on nearly 50 films, beginning with A Man Called Dagger: The early, low-budget films we did together were really our schooling, in that you had to make do with what you had and use your imagination. As far as László was concerned, there were no cheap pictures — cheap budgets, yes, but no cheap pictures. Every shot was worthwhile and a learning experience.

He was a good man to work with both technically and artistically, which is rare. He gave you technical reasons for answers, not just opinion. He went to the trouble to find out not only what worked but why it worked. His philosophy was do the very best you can with what you have; if you didn’t try, he had no patience for you.

Cinematography was in László’s soul. He came in when there were radical changes in film speed, lights, and all kinds of other gear, but he never went overboard with new equipment. He did what was best for each picture. People say he didn’t have a signature style, but I think his lighting was one of his styles: it played the source and it looked real. He was also a great handheld cameraman.

“Rack focusing was being used in commercials, but not so much in films. László became not just an expert at it, but a maestro.”

— Richmond “Aggie” Aguilar

We had no idea Easy Rider would have such an impact. [It was the beginning] of location filming, with independent producers and independent stories, and that really became our specialty. We began making special equipment for location work. We made a set of small Soft Lites, with a reflector that was big enough to be a soft light yet small and light enough to hang very simply and up higher; the units had no socket assembly on them. We minimized everything. All of our stands had a leveling leg so that no matter where we were, we could level up the thing and it wouldn’t roll away. We took the wheels off. On Easy Rider, László used a 25-250mm Angenieux zoom, which was more-or-less new to the industry. Rack focusing was being used in commercials, but not so much in films. László became not just an expert at it, but a maestro.

When we were working at Columbia on Labyrinth [a.k.a. A Reflection of Fear], a film that Billy Fraker [ASC] directed, we were given the studio’s senior electricians. These guys were in their 60s and 70s and we were the young upstarts, so they didn’t have much use for us. They refused to do the work. At one point, I told the [key electrician] to set up some lights down a hallway, and he messed around but didn’t do much. So László said to him, ‘Come over here and look through the camera and see where that light plays on the wall.’ These guys had never looked through a camera — in fact, they’d been told to stay away from it because that was the cameraman’s territory. Well, after that electrician looked through the camera, he went back and forth down that hallway a half-dozen times, adjusting that light. He really appreciated looking through the camera and seeing his work.

László was always very positive and got along well with people both above and below the line. He never put down any suggestion; he had a way of agreeing with people and bringing them around, but without any kind of rejection of the other person or his idea. Nobody ever got offended.

László always gave me the incentive to do the best I could. I think he brought that out in everybody, and he always did it by example.

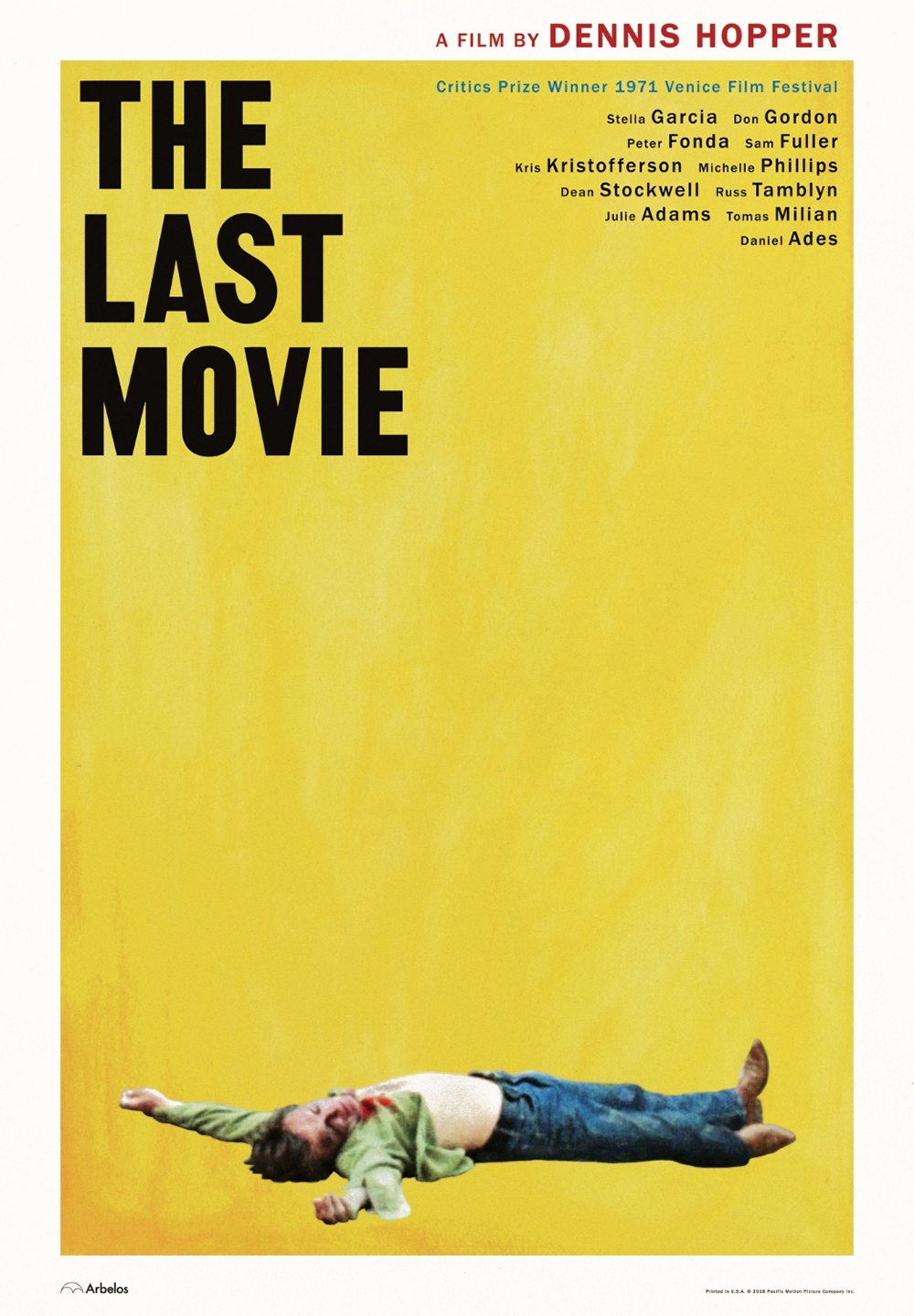

Dennis Hopper, director of Easy Rider and The Last Movie: László was the greatest telephoto operator I know of. He was a great cinematographer. His lighting was quick, fast and complete. We shot Easy Rider in five weeks going through and shooting in five different states. We used a fast film that had not been used before in movies. I would never have been able to make Easy Rider without László and Paul Lewis, my production manager, who brought Mr. Kovacs to me. Paul said, ‘This is your man,’ and László certainly was. My vision[s] for Easy Rider and The Last Movie were simple but very complicated. Since I was starring in and directing in both films, hand signals were the way we communicated. That’s how in the same groove we were. [László was] a wonderful, charming, hard-working genius. We are all lucky to have been his friend. He will be with us forever through his films and our collective memory. God bless László Kovács!

“I’m sorry he’s gone, but I’m very glad he was here.”

— Richard Rush

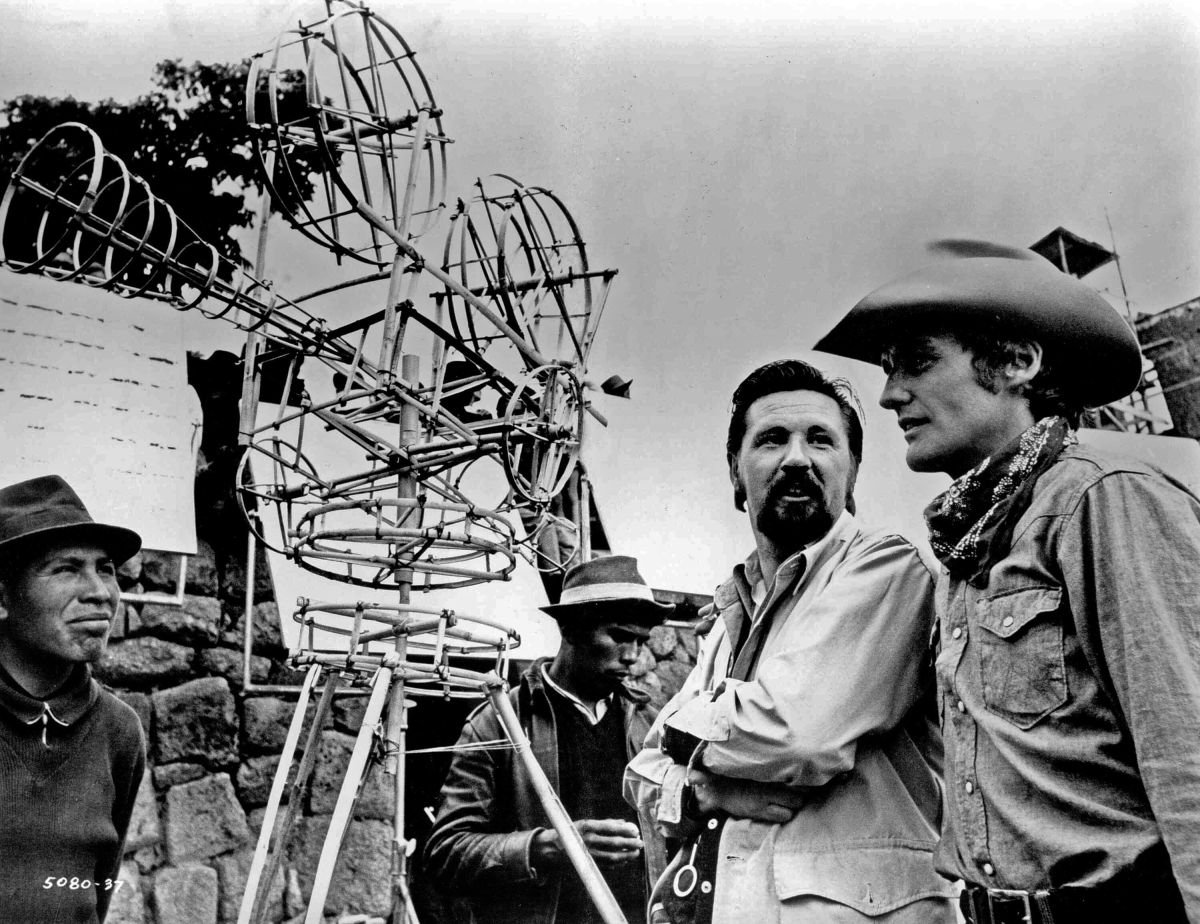

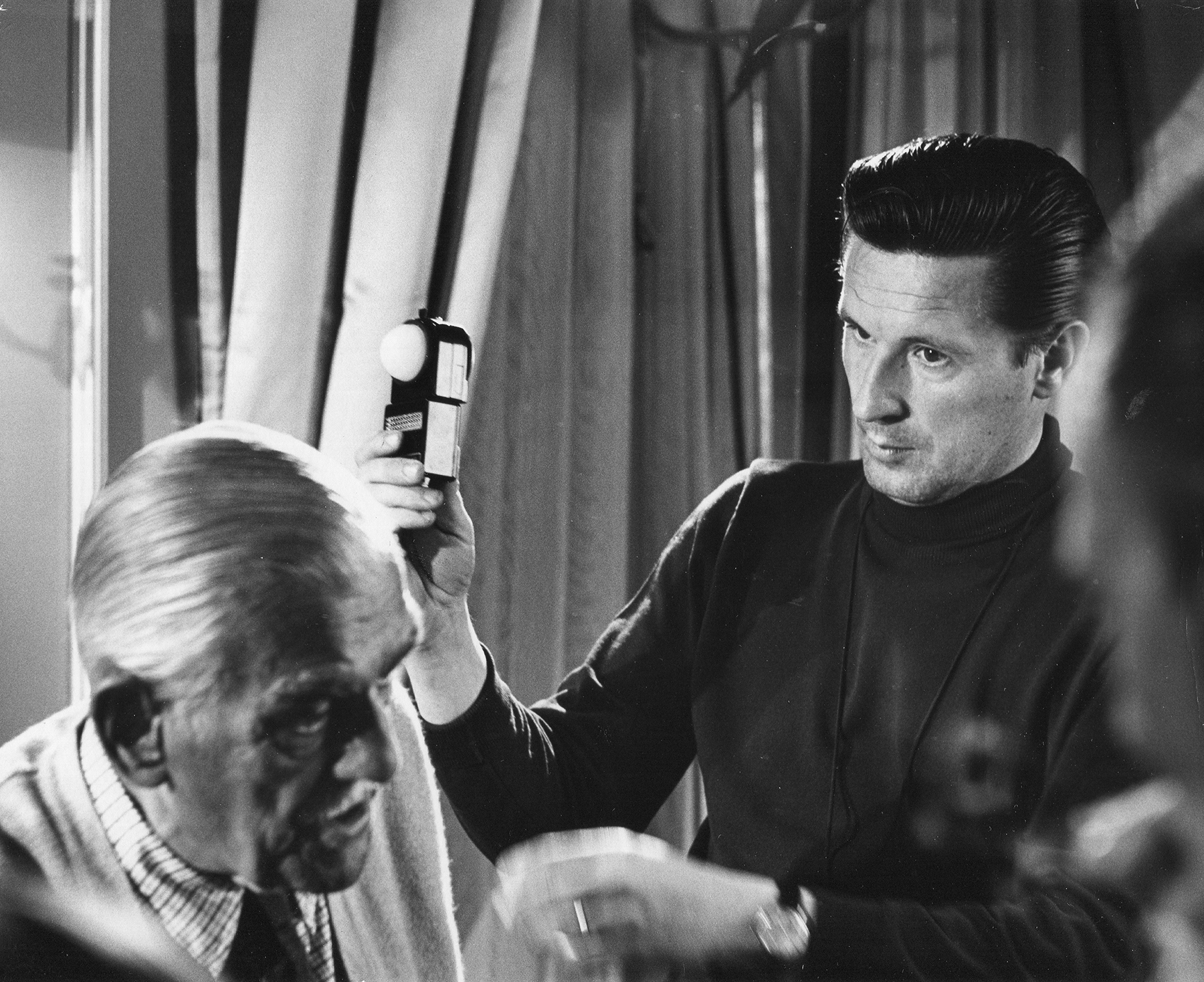

Richard Rush, director of A Man Called Dagger, Hell’s Angels on Wheels, The Savage Seven, Psych-Out, Getting Straight and Freebie and the Bean: I was going to do A Man Called Dagger, a spoof of James Bond, and I was looking for a good director of photography. László was recommended to me. He had never done a feature before.

He turned out to be the best handheld operator in the country, probably in the world. This was the pre-Steadicam days, and he had a beautifully fluid action style. He also could shoot with both eyes open; that is, he could see where he was and realize where to move and how to resolve the shot. He was mentally dexterous enough to work aperture and focus while he was shooting. He was also tireless.

My most indelible memory of him [involves] one film [in which] I wanted this whole row of Indians to come over a hill, whooping and screaming. I needed a low-angle shot and couldn’t get as low as I wanted. László knew I wasn’t happy about that, so he gathered the crew, dug a huge hole and put the dolly in it.

I’m sorry he’s gone, but I’m very glad he was here.

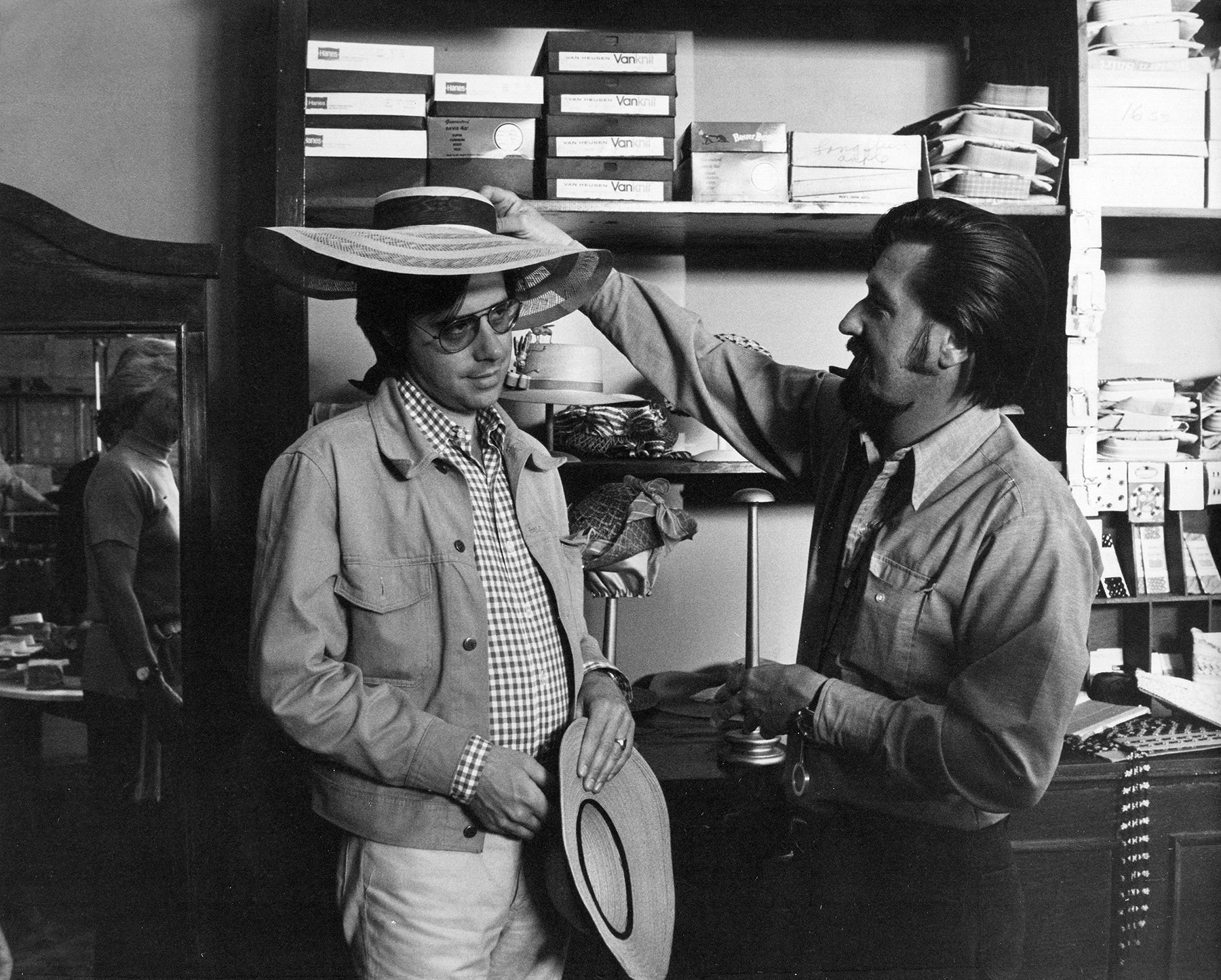

Peter Bogdanovich, director of Targets; What’s Up, Doc?; Paper Moon; At Long Last Love; Nickelodeon and Mask (excerpted from an interview on NPR’s “All Things Considered”): I met László when I was preparing to direct Targets, a Roger Corman film, in 1967. I was looking for a director of photography, and Roger told me, ‘We have quite a good cameraman. His name is Leslie László. He is shooting a picture for me called The Girl in the Invisible Bikini.’ He sent Leslie to see me. In walks this good-looking, dark-haired Hungarian who had a fairly thick accent. I had never seen anything he shot, but after we spoke for about 10 minutes I hired him on the spot. I remember asking him if Leslie was his real name, because it didn’t sound Hungarian. He said, ‘No, but nobody knows how to pronounce László, so I call myself Leslie. When I make a good picture one day, I will use my real name.’ When we finished Targets, I asked him how he wanted to be billed. He said, ‘I finally made a good picture. Let’s call me László Kovács.’

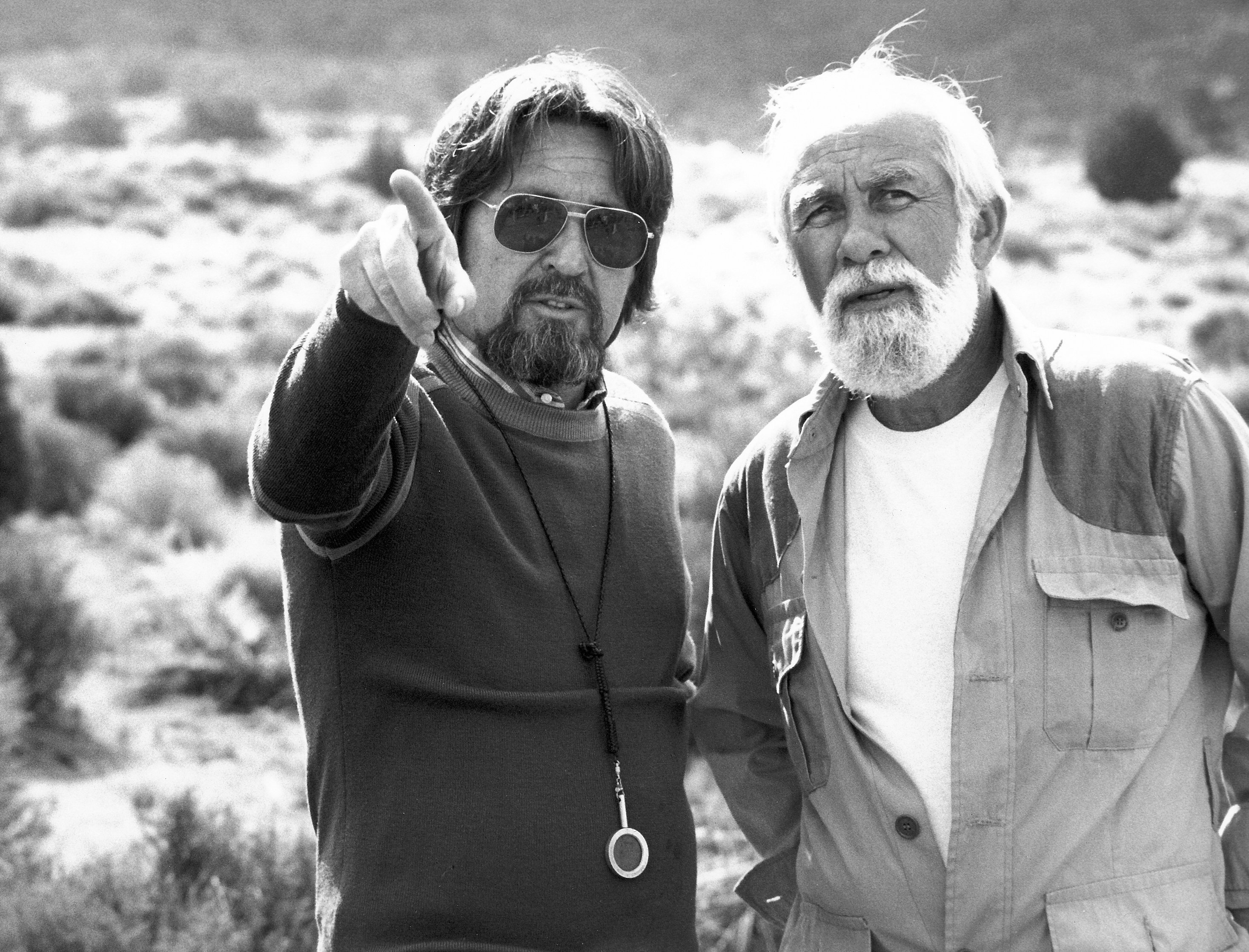

Bob Rafelson, director of Five Easy Pieces and The King of Marvin Gardens: Early this summer I flew to Los Angeles to be interviewed for a documentary about László and Vilmos and their 50-year journey since they arrived in the United States. There were pictures of László alone and of us together strewn all over the room. Someone said László hadn’t come because he wasn’t feeling well. After I arrived back in Aspen, a friend who had worked with László on commercials asked me how it went. I told her it was fine, but I wished László had been there so I could have embraced him. He was a beautiful man. I will miss him.

William A. Fraker, ASC, director of A Reflection of Fear and The Legend of the Lone Ranger: László was truly an artist. One of the marvelous things about him was how he welcomed challenges. He had that innate ability to look at a challenge creatively and accept it with great vigor. I asked him to shoot my two films because I liked his style — he had a more international approach to subject matter — and working with him was a dream. He was so positive about everything. If I wanted to do a certain thing that might seem impossible to a lot of people, László would say, ‘Billy, we do it.’

Graeme Clifford, director of Frances and Ruby Cairo: I first met László when we were both working on a film for Bob Altman, That Cold Day in the Park, up in Canada. I was the second assistant director and the assistant editor. I respected Laszlo greatly from that point on, and [when I started directing commercials] I asked him to do some with me. When I got my first feature as a director, Frances, I immediately asked László if he would do it.

Frances was one of those movies where everything just fell into place. You only get one or two of those in your lifetime. [I like] stories that don’t have tidy endings. European movies are like that; they have endings that leave you thinking. With Frances, especially, I felt it was important to find a cinematographer who had a penchant for European movies. László did, and that’s the way he photographed. For him, what wasn’t quite in the frame was just as important as what was in it. In that regard, he reminded me of the artist Edgar Degas, whose compositions frequently include half of a ballet dancer or the hand of somebody who isn’t in the frame — you want to take a Degas frame and say, ‘Pan left.’ I love that about movies, too: things left undone, ideas that aren’t quite complete. I always felt László got that without my having to even talk about it. The way he shot, the story wasn’t taking place only within the frame, it was also taking place outside the boundaries of the frame. You could feel it but not quite see it.

After Frances, László and I did some more commercials together. Then I got Ruby Cairo, and that seemed another perfect opportunity to work with him. The collaborative process between us was always so easy. I had a rapport with him and liked his cinematography, the crispness of it. I liked his eye for detail and the way he framed shots. He was also very respectful of the people he worked with.

László also had a wonderful eye for excellent food and great wine. He knew how to relax and live life to the fullest. Traveling with him was a wonderful experience. On Ruby Cairo, we spent a month in Cairo and then shot in Greece, Germany and Mexico. Another time we went to the Caribbean to shoot a commercial campaign for American Express. We went all over the Caribbean looking for locations, then rented a four-mast schooner to shoot on for a week. It was a dream job and the most fun I’d ever had. With László it wasn’t just a working relationship, it was an all-encompassing social and life experience.

László was always so generous with his knowledge and his time. He liked being around young people. When I started teaching at the AFI six years ago, he came regularly and talked to my directing class about the interaction between the cinematographer and the director. And, of course, he talked to my cinematography class. He came to talk to my class not long before he died. Even though he wasn’t well, he dragged himself to the lecture hall.

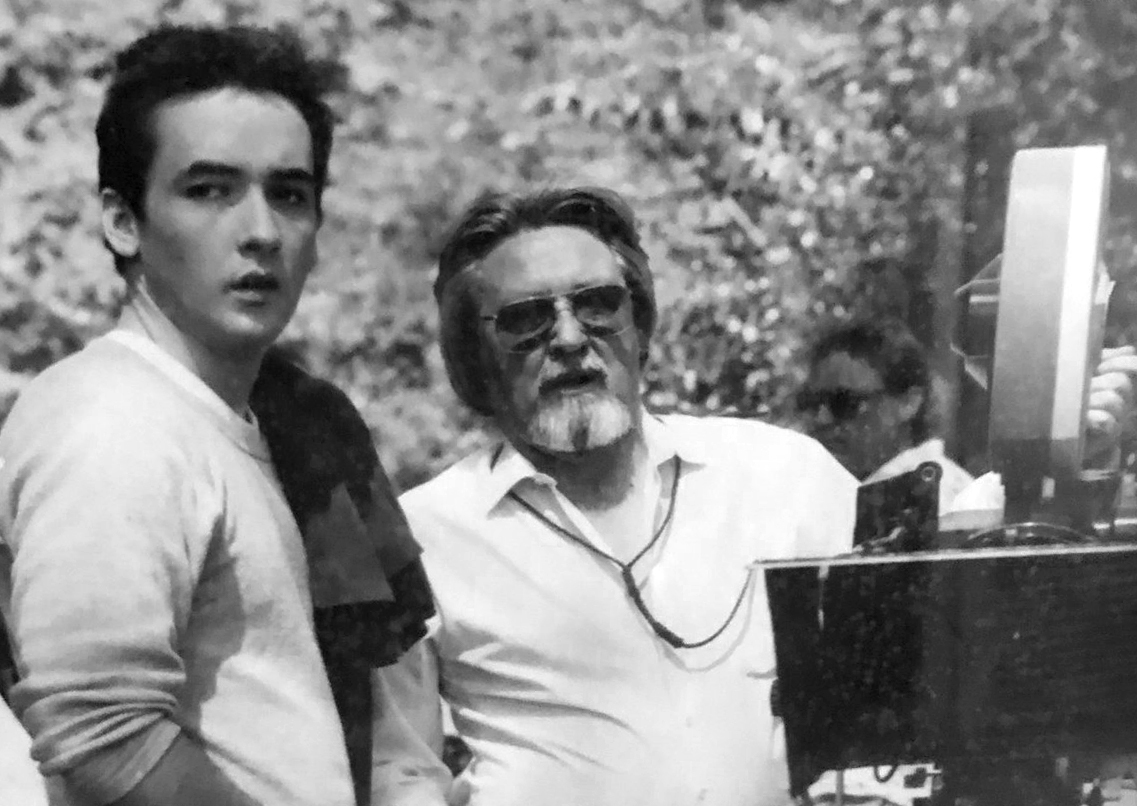

Cameron Crowe, director of Say Anything … : [As a first-time director], I was obsessed with learning how to stage a scene. The math of that was daunting to me at first, because I’d come from the world of writing. Everybody functions beautifully in your mind, but how do you do it for the camera? I worked on it every day with László, [trying to find] the visual heart of the scene. When do you get fancy? (Usually never.) When do you get personal? (Whenever possible.) László really knew the script. He taught me that staging works from the inside out. He loved the characters. The camera is an extension of their souls. It’s clear in all his other [movies] too, from Easy Rider to Paper Moon to Shampoo. You remember the characters first, and the lovely presentation second … but the Kovacs touch is the elixir — it’s gently compelling and soulful. There was a sly, masterly touch that came from László himself. Often it was nearly invisible, but the effect could be seismic.

“I said to László, ‘Boy, this isn’t going to look good in dailies.’ And László calmly leaned over and whispered, ‘Don’t worry, there’s no film in the camera.’’’

— Cameron Crowe

I’ll give you an example. On Say Anything … John Cusack knew Lloyd Dobler had potential, but he was very wary of the execution of the movie. He was often unsure if he was truly making a movie of substance, and not just another teen-genre movie like the ones he’d just done. He didn’t want to put on the graduation gown or deal with any of the trappings of the so-called genre. We’d debated endlessly over a scene that was important to both László and me: the boombox scene [in which the lovesick Dobler holds up a boombox playing Peter Gabriel’s ‘In Your Eyes’]. Cusack had dug in — he felt it was a subservient scene where Lloyd was weak. Why was he weak? Why does he have to ‘hold it up?’ He was very worried the character might come off like a wimp. We tried the scene once, and it didn’t work; the attitude was all wrong. I’m saying to John, ‘You’ve got to do another one for me. We don’t have it and it’s important to me.’ And Cusack says, ‘I want to try it with that boombox on the car beside me and I’ve got my arms folded and I’m defiant. She broke up with me! I’m pissed!’

I knew there wasn’t time to shoot a version of the scene that wouldn’t work. Of course, Laszlo is in on all this, hanging right over my shoulder — that seasoned, soulful master, not missing a thing. [He knew] I was dying, because the defiance wasn’t the character and this wasn’t the way to shoot the scene. But László says, ‘We will shoot it at the end of the day.’ And Cusack lit up —‘Fantastic, I just want another shot at it where I don’t hold up that box.’ So we have a very long day, and at the end Cusack is out on the street doing the scene with the boombox sitting on a car and an angry, defiant look on his face. Everybody knew it wasn’t right for the movie, but László knew it was important for the dynamic between the director and the star. As the scene stretched on, getting worse and worse, I said to László, ‘Boy, this isn’t going to look good in dailies.’ And László calmly leaned over and whispered, ‘Don’t worry, there’s no film in the camera.’

That was László helping a first-time director. Johnny and I have laughed about this since, but the story doesn’t end there — it ends with the last shot of the movie. We still don’t have the boombox scene right, and the sun is going down. László goes into this park across the street from the 7-11 off Lankershim Boulevard, where we had picked up another little shot, and finds this beautiful part of a bike path. He says to me, ‘We’ll do a push-in here of the boombox scene, but let’s hurry. We are losing the light!’ His crew, who’d been with him on most of his movies, snapped into action and set up the shot in no time flat. The sun was going down. Cusack did it one more time, boom box aloft. His discomfort with the scene is now perfectly in character. It’s playing as a stoic guy gobsmacked by love and devotion. We did the push-in and it was beautiful, and suddenly the light was gone. But we had it, and it was everything. The last shot on the last day of the movie. Without it, I have no movie in the same form.

That was László, working selflessly and [with] teamwork, never with a swagger, and never forgetting what the story was.

Daryn Okada, ASC president: László was an extraordinary artist and human being. He was chairman of the ASC Education Committee for many years and was tireless in his efforts to support young filmmakers. He envisioned the annual ASC Heritage Award as a tangible way for us to inspire talented, young cinematographers to pursue their dreams. It was his idea to annually dedicate the award to the memories of different late cinematographers.

Frederic Goodich, ASC: In Godard’s Breathless, a character named Laszlo Kovacs is talked about but never seen. Every time I saw the film I’d wonder who Laszlo Kovacs was. The name haunted me. A decade later, when I saw Paper Moon, I figured I had finally identified the mystery man from Breathless. At the screening, I had the chance to meet László Kovács. How he had achieved that film’s amazing, luminous black-and-white imagery was something I was hungry to understand. After the screening, László graciously stayed for a Q&A. I learned a lot about craft, but I also came away with something more profound: the example of a major artist being accessible to a younger generation, generous with his time and willing to freely share his knowledge. I’d also met the man who would inspire me to become a teacher.

As a result of my association with Cinematographer’s Day, László and I began to spend quality time together. When we presented a 10-film retrospective of László’s work, in 2002, he invited me to the lab to screen prints from newly restored negatives. We would have lunch at Hoboken, a little eatery in Westwood, and talk about cinematographers, directors, film and the people we both knew. I was especially inspired and fascinated by his sincere love of people’s eccentricities. He was a great storyteller, with or without a camera in his hands. László had hung out with some mythic people and participated in the making of some iconic films. When I watch these pictures, something about his way of visualizing and expressing what he saw from moment to moment unerringly captures my attention.

At the 2002 retrospective, I finally had the opportunity to ask Laszlo whether he had worked for Godard before coming to America. No, László replied, the name in Breathless was just a coincidence. He hadn’t the slightest idea who that Laszlo Kovacs was, and he was curious, too.

Last June, at the Cinegear Expo, I spent some time with László at the ASC’s booth. He’d been ill, but that day he looked like a new man, and his energy was great. By 5 p.m. on the last day of the show, most of the attendees had left and exhibitors were packing up their wares. László was talking to a student from France. I reminded him it was time to head home. He said okay and stood up, but, after realizing the student had more questions, he sat down again to answer them. It took two more urgings from me to get us onto the last bus, but not before László, the ‘last man standing,’ had given the student his contact info and encouraged him to attend Camerimage in Poland.

“When viewing László’s greatest works, one senses that tradition of classic Hollywood studio cinematography being absorbed, filtered and then re-expressed in a modern fashion by a foreigner who loved that era of cinema.”

— M. David Mullen, ASC

David Mullen, ASC: In various interviews László gave during his career, he often mentioned classic American black-and-white movies like Citizen Kane and Casablanca as being memorable viewing experiences while he was a film student in Hungary. When viewing László’s greatest works, one senses that tradition of classic Hollywood studio cinematography being absorbed, filtered and then re-expressed in a modern fashion by a foreigner who loved that era of cinema. And like those great cinematographers of the 1930s and ’40s, László could master any genre he was hired to photograph.

Steven Fierberg, ASC: One of the less-talked-about job requirements of the cinematographer is the mise en scène, or setting of the camera. There are directors who do this on their own, directors who wish to collaborate with the cinematographer, and directors who really need the cinematographer to refine the staging and present the shot. No matter which type of director he worked with, László always came up with great shots that told the story in an emotionally involved way. Even when he worked with a first-time director, the camera was always in the right place. My favorite mise en scène of his is in Five Easy Pieces. He perfectly captures the existential coarseness of the oil field, the passion of Jack Nicholson’s one-night stand, the terribly tragic separation of the self-hating Jack and the lost Karen Black as he deserts her at the gas station. With little or no lighting, he captures the emotional subtext of the story with images that need no sound to be understood.

“If character is indicated by what you do when no one is looking, then László’s work shows that he had it in spades.”

— Richard Crudo, ASC

Once, when he was teaching a Local 600 lighting seminar, László made a statement about shot selection that I have always remembered. He said, ‘Don’t do a shot at the beginning of the scene that is so wide you see the whole room. It’s much more interesting to have seen the room only by the end of the scene, through the combination of the shots you have done.’

To make a great film, the shots have to be right. With László shooting, any director could be sure his or her story would be told with visual power and elegance.

Dennis Schaefer and Larry Salvato (from their book Masters of Light): A self-confirmed workaholic, László Kovács has worked with a great variety of directors. One thing, however, that remains constant in his work is the organic matching of a visual look and style to each specific film. He constantly emphasizes that each film has its own character and that the cinematographer’s approach to it must come from the material. That’s why none of his films look the same. His slight European accent gives his voice an air of artistic authority and, indeed, he has a different way of ‘seeing’ than a native American. His mind does not work on an assembly-line basis but on a loving, handcrafted level.

John Bailey, ASC: The thing I remember most about László — and the thing I really loved — was how versatile he was throughout his career. He followed in the great Hollywood tradition of cinematographers, ultimate professionals who could move through many different styles and genres. He was always moving back and forth between independents and what would be considered mainstream films.

Ironically, that very versatility, that ability to work in completely different ways, was also one of the reasons I think his work never received its full due in terms of peer recognition. He earned wonderful awards but was never recognized with Academy nominations. I have always been sort of appalled and disappointed that my own branch of the Academy never nominated him. For whatever reason, cinematographers seem to reserve more of their adulation and recognition for cinematographers who have signature styles. The more obviously flashy cinematographer gets the nomination rather than somebody like László, who spent his career serving the material in the most elegant way.

This is in no way intended as a disparagement of cinematographers who have a signature style, but there was something so lovely about László in his selflessness, his lack of ego as a director of photography, his willingness to submerge himself and his work into whatever seemed most appropriate for the given material and director. I have always found that an amazing gift, and it’s an approach I’ve tried to emulate.

Some of László’s films are great, some are okay and some are bad, but he never did mediocre work. In the great tradition of Hollywood’s best, he always rose to his highest level regardless of the material.

Richard Crudo, ASC: Everyone talks about László’s versatility, and although that aspect of his talent is undeniable, people outside our immediate world — even knowledgeable and sophisticated ones — often don’t understand just how difficult it is to be so adaptable while at the same time remaining so innovative and consistent.

No matter how experienced you are as a cinematographer, there’s always an element of discovery that takes place when you light a set. Whether or not you’ve held strong ideas about what you want to do, it becomes immaterial the moment you’re actually faced with doing it. Our collaborative natures kick in. Things change, theories are proven or discarded, truths are revealed. But the light that hits the emulsion is the cinematographer’s light, and it’s our gift to be able to turn everyone’s contribution into palpable reality. When all cylinders are firing, we create a visual through-line in which our work hangs together seamlessly. László was an absolute master at this.

Unlike some of our most celebrated cinematographers whose styles are instantly recognizable — and whose overblown egos are often equally remarkable — László brought an admirable humility to his work. At the root of his approach was a simple tenet we all need to be reminded of from time to time: just tell the story. Of course, flash is occasionally called for, and László could certainly pull that from his bag when he needed to. But more often, the tougher moments of our days are the internal ones. They occur when we’re faced with a choice between the appropriate and the self-aggrandizing. If character is indicated by what you do when no one is looking, then László’s work shows that he had it in spades. And as we review his career, we see that by not calling attention to himself, he fostered the precisely opposite effect. What a triumph! We should all be thankful for it.