Lighting The Day of the Jackal's Twisty Opening Scene

A cinematographer on the spy-thriller series shares the lighting plan for its very first scene, and breaks down his approach beat by beat.

When Brian Kirk, director of the first three episodes of The Day of the Jackal, signed on to the project, one core idea drew him in: that the series’ world would be built entirely on deception. Writer Ronan Bennett had described the show as being about liars and the lies they tell — liars that lie about everything, all the time. Brian took this concept further, envisioning we the filmmakers as the most trusted con artists. The audience would be fed carefully constructed information from unreliable narrators, their intentions hidden behind charm, precision and cinematic allure. The ultimate goal: to make viewers complicit in the duplicity of the show’s protagonist, the elite international assassin Alex “The Jackal” Duggan (Eddie Redmayne).

This idea manifests immediately in the first scene of Episode 1. The scene appears to follow a seemingly ordinary man named Ralph Becker checking his appearance in a bathroom mirror before work, but in truth, this is not Ralph at all. The real Ralph lies dead in the other room, and it is in fact the Jackal whom we observe rehearsing Ralph’s accent and adjusting his appearance to assume his identity in the real world.

Brian wanted this opening scene to establish the show’s thematic and philosophical framework: disorientation, ambiguity and duality. We wanted to lure the audience in, teasing with just enough information to intrigue the viewer, encouraging them to speculate about what lies beyond the frame. To preserve that sense of enigma, we chose to cover the scene in a single, fluid camera move, allowing “Ralph” to lead the viewer through the space, with each new element of the imagery adding to the narrative puzzle.

We begin the scene on a close-up of a Dictaphone, then reveal Ralph as he places a lanyard and name badge over his head. As he walks through the space, a concealed gun briefly appears in his waistband. Then, the twist: a body slumped in a chair — the real Ralph. The two are doppelgängers. Finally, the impostor flees the scene, focused and determined.

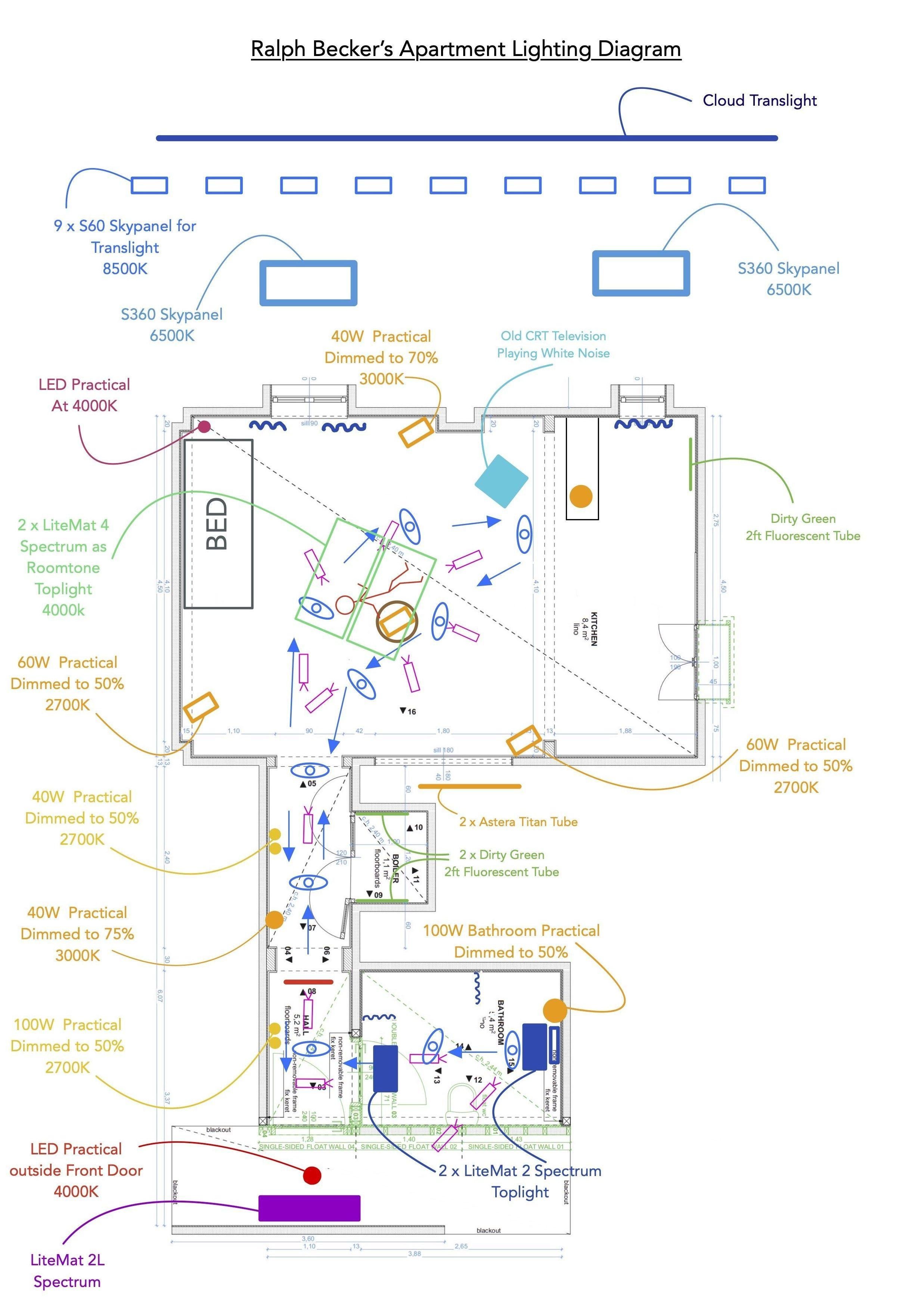

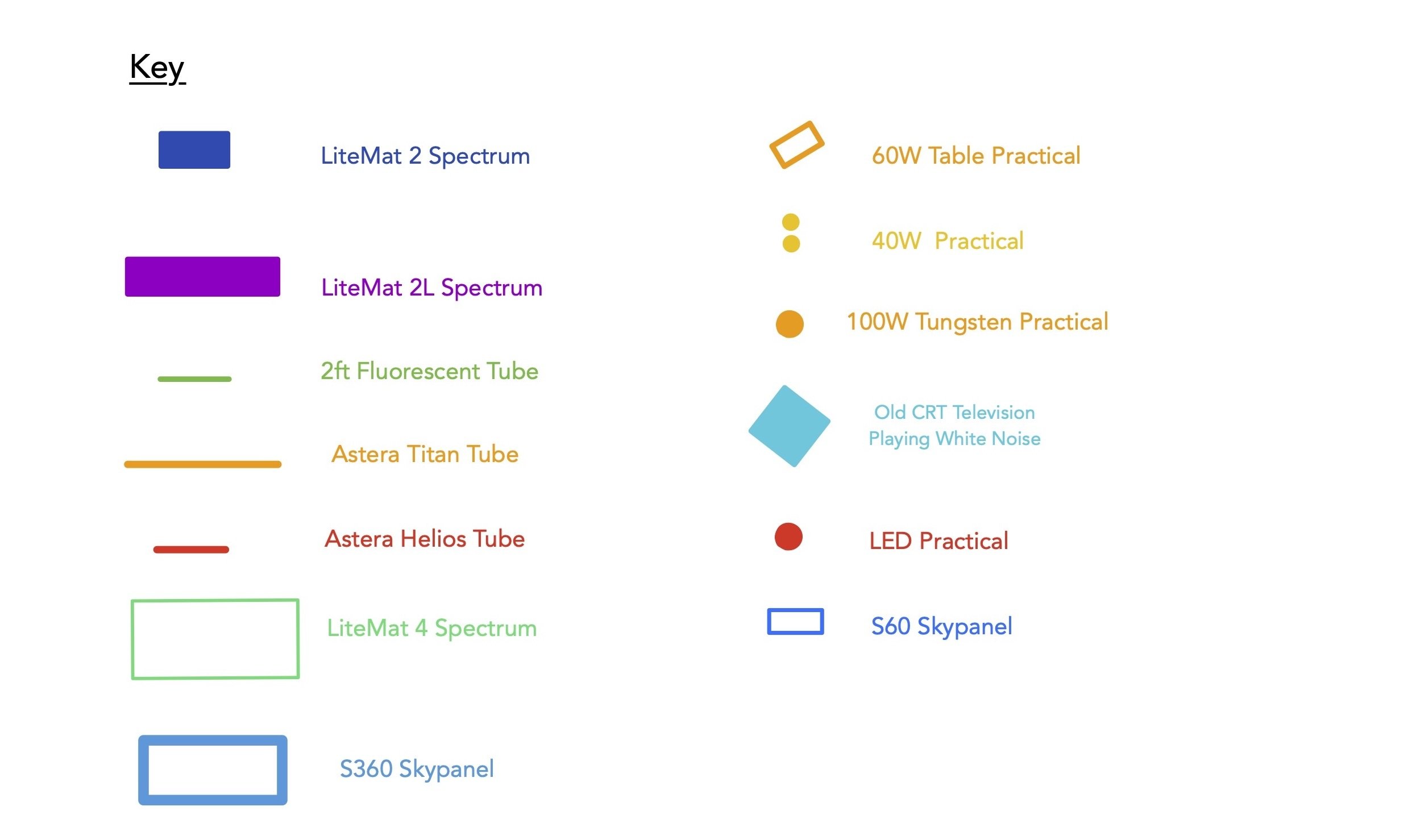

This two-minute shot evolved through multiple stages of rehearsal. First, we storyboarded and blocked the sequence in a meeting room, dissecting each beat. Then, we marked out a rough layout using tape to establish walls, mirrors, doors, and furniture. Finally, we moved into the set itself, refining each section in sync with Eddie’s performance. Once the choreography was set, I began to shape the lighting with gaffer Szabolcs Sipos. (See our lighting plan in the diagram and corresponding key below.)

There is no single formula for lighting a scene. Sometimes the space dictates the light; sometimes it's story or atmosphere. In this case, it was all three. Ralph’s world needed to feel as layered and deceitful as the Jackal himself. Production designer Richard Bullock created a lived-in, nicotine-stained bedsit: half-hermit, half-nightcrawler. Overflowing ashtrays, solitary meals, a lone chair facing a TV. This space had to tell Ralph’s story before we even saw his body.

I opted for compartmentalized lighting — small pools of illumination to reveal only fragments of the room at a time. A glimpse of a bed, the white noise of an old TV, the upturned lamp next to the body showing signs of the struggle. The goal was to guide the viewer’s eye within an evolving frame and enhance the mystery of the space.

We began with the bathroom. I wanted contrast on the face of “Ralph,” accentuating his lined features without too much fill. To achieve this with such a low ceiling, I decided that a practical approach was best. After testing various fittings, we landed on a crystal-faceted globe with a clear 100W bulb. This was paired with a very thin, soft LED fitting above Eddie’s head as a kind of “roomtone,” with a smoky blue tint, to enhance the blacks and add dimensionality to reflective surfaces like the Dictaphone.

As “Ralph” moves into the hallway, a second roomtone fitting was in place to raise the exposure of his features just slightly above black — three to four stops below key — right at the bottom of the curve. Next, the gun appears tucked into his waistband. Guns, mobile phones, detonators… these are all difficult things to light — small, black boxes always hidden in half-light. Rather than lighting the gun directly, we chose to use a practical with a large shade on a low table in the hallway. The gun reflects as a specular highlight for a moment, just long enough for the viewer to register the shape and intention.

As “Ralph” enters the main room, we establish a subtle sense of time of day. Outside the windows, a cloud Translight is lit at a low level in cool tones, to simulate a north-facing, dusky sky. Two Arri Skypanel S360-Cs push this ambient light into the space, giving the bed and kitchen a hazy blue hue to counterpoint the warmth of the isolated domain.

The reveal of the body — our first view of the real Ralph — required a compromise. We had to choose where to place the dramatic weight: on the first glimpse of the body, or on the climactic face-to-face moment. Which beat would require more intrigue and drama? We chose the latter. Front-lighting the body’s first appearance allowed for dramatic edge-lighting for the two shot moment. Enhancing this, we used a Tiffen Smoque filter, allowing the bulb of the practical to dig into faces and to bloom and fade, increasing the interactive quality between light and character as the camera moves. As with the bathroom, there is a “roomtone” above the body — two low-profile LED fittings at a very low exposure to add the smokey blue to the shadow side of our two Ralphs.

Practical lights around the room added texture and depth and help to pick out the set while allowing the scene to feel “dark." They also helped to establish the color palette: Warm tungsten tones between 2,800K and 3,000K dominate the interior, the daylight outside remains a desaturated indigo-blue, and background sources were tuned even warmer (down to 1,700K) to help the practical key lights feel neutral in contrast. I often mix a wide range of color temperatures and tints in pursuit of making the imagery feel more complex and real.

The scene ends with the Jackal, still disguised as Ralph, returning to the hallway. As he stands momentarily, a practical placed at eye level gives him a final glint of menace before he steps out, fleeing the scene of the crime.

Long, moving shots that rotate more than 180 degrees are inherently challenging, both technologically and conceptually. Our approach leaned into practical lighting for character interaction, with more traditional film lights used to sculpt atmosphere. We were looking to discover harmony between light, space and performance, and allowing each of those elements to inform and enrich one another.

Ultimately, our aim was not just to make something visually interesting, but to draw the audience deeper into a world of deception. By embracing complexity, imperfection, and the interplay of camera and performance, we hoped to reflect the core truth of the show — that nothing is as it seems.

The Day of the Jackal is now available to stream on Peacock. An episode of the ASC's Clubhouse Conversations video series, exploring the cinematography of the show, will premiere June 4.