Inside the Aerial and Underwater Cinematography of Mission: Impossible — The Final Reckoning

Cinematographer Fraser Taggart details the rigorous prep, camera rigs, lighting and lens choices, and collaboration across departments that made the film's biplane and submarine sequences possible.

Going to Extremes: Shooting the Biplane Sequence

It's always difficult to make a plane sequence different. You and your crew set lots of meetings, and someone will inevitably talk about a film like The Blue Max, shot in 1966. There’s always something comparable to what you're trying to achieve, so you're always trying to give your scene a different edge. For the flight sequence in Mission: Impossible – The Final Reckoning, in which Ethan (Tom Cruise) chases Gabriel (Esai Morales) through the skies of South Africa, we wanted audiences to feel as if they're participating, that they're at the heart of the action.

To help achieve this, we used Z Cam cameras hard-mounted to our planes, along with air-to-air coverage. I’d first used Z Cams for the Fiat chase scene in Mission: Impossible – Dead Reckoning Part One, because a Fiat is so small you can’t put normal rigs on it — it would tip over. Paired with lightweight Zeiss CP.3 lenses, the Z Cams gave that scene a different feel, a bit of character compared to the other car-chase scenes in the film. They’re very compact digital cameras, and their sensor sits in very well with the Venice, which was our main camera on both Dead Reckoning and Final Reckoning. So, we carried those over to the biplane sequence in Final Reckoning. We went into the final grade early to ensure we wouldn't have any problems with the shutter. Quite often with small cameras, you'll get shutter problems that give you a “step effect” where you'll get edge bleed — a blurred frame on the edge — but the Z Cam proved itself. I asked Z Cam to make small adjustments to the camera, and they were very receptive and did so much to help. They even built us a small Rialto, taking the sensor and the lens off so we could have a limited extension system that would help us position our cameras in spots where we couldn't even fit the Z Cam.

These mounts and camera affect the aerodynamics of the aircraft, so we tested and tested to see how many we could get onto the biplanes to get as much coverage as possible, and to be able to dynamically cut the action. We worked with our pilots to ensure that the planes were stable and safe, and then we gradually pushed everything a little bit more so the audience could feel they’re right there with the characters, experiencing a mid-air, hand-to-hand fight.

Tom being out on the wing created another “drag factor.” You have to calculate it: If we put two mounts on the right-hand side of the aircraft and one on the left, will that balance out? After we did those calculations, the pilots would go on test flights. It’s all incredibly complicated — a slow process.

Sometimes we'd want to shoot the plane from farther away, so my teams of grips and Dani Rose of CineAero devised extensions similar to lances or javelins, which enabled to extend our hardmounts. We could position them between the biplane wings and get a camera about 8 feet out in front of the wing to capture Tom’s performance.

The planes’ airframes were about 80 years old and had their original engines, which we thoroughly stripped and rebuilt. They had canvas wings that we had to reinforce, which was another aerodynamic nightmare because you’re putting more weight onto the aircraft. We had a few incidents where the aerial-build team had to chop wings, working through the night to ensure the aircraft were fit to fly in the morning. It’s what you'd imagine it was like being in a Spitfire squadron during the Second World War: The planes would fly out on a sortie and get a bit shot up, and then the mechanics would work all night to get them ready again for the morning’s mission. We’d even change engines overnight. It was amazing.

More on the Cinematography of the Mission: Impossible Series

Stephen Burum, ASC Shoots Mission: Impossible

Robert Elswit, ASC Shoots Mission: Impossible — Rogue Nation

We had three of each aircraft, and we’d leapfrog mounts, so while they were up flying and we were capturing shots of Tom going in for a punch on Esai, we'd be rigging the Esai side of the shot. Even though you test rigs and pick your angles, once the actors are up there in 80-mph winds, their bodies don’t always do what you think they will within the frame. So getting all the coverage we needed was a time-consuming operation. Still, we made room to experiment every day. McQ [writer/director Christopher McQuarrie] would say, “Guys, I really want to get an angle up on the top of this wing here.” Then we’d ask the pilots, “How do we rig it safely?” We were endeavoring every day to come up with something different. It was a process of coverage that took over a year with testing. We shot on location for 4 1/2 months in South Africa, but once McQ started to cut the footage, we realized there were essential bits missing. Budget-wise, we couldn’t go back to South Africa, so we shot in England, in Oxfordshire and Cambridgeshire. Despite some initial struggles, we managed to match our South African light there, simply by sitting tight and waiting for favorable conditions.

When we were planning the sequence, we looked at a lot of aircraft. Tom and McQ really loved this silver-and-blue aircraft we scouted in Norway, but we would be shooting on location in South Africa, in very contrasty, hard light; if Tom was going to have a silver wing beneath him, I didn’t know how I could do the exposures, and he’d cook in the heat of the reflections. We ended up with a red-and-yellow plane, classic biplane colors that are distinct, so audiences can immediately identify which aircraft is which.

For our air-to-air coverage, we had two helicopters with different rigs to maintain the speed that would allow us to capture our footage quickly. One of these helicopters was rigged with a Shotover K1 mount, on which the camera was paired with a 36-43.5mm Angénieux lens; the second was mounted with a Shotover F1, on which the camera was paired with a Fujinon 19-45mm lens. By leapfrogging between these two aircrafts, our crew could practically and efficiently switch between the two lens looks designed for the scene. Long lenses would have been the more conventional choice to shoot aerial footage, but we wanted viewers to feel like they’re sitting on the tail of the plane — which is when the Fujinon came into play — so we chased the biplane from about 5 feet behind it. I've done a lot of aerial photography, but on this shoot, sitting in that chase helicopter as our brilliant pilot got right on the plane's tail, I was forcing myself back into my seat. It was always safe, but we flew into some positions that had me thinking, “That's tasty.”

A "Yak" fixed-wing aircraft, flown by our steerman pilots Steven Jones and Lee Proudfoot and rigged with a Shotover F1 mount on its small wing tip, served as another asset for our crew, enabling us to capture alternate angles of the action. The Yak allowed us to pull the biplanes, which would not have been possible with the use of our helicopters. Aerial cinematographer Phil Arntz was tasked with capturing key moments from onboard this plane — particularly for “pulling shots,” in which the camera is angled toward the front of the biplanes.

Although our pursuit helicopters and the Yak were integral to the shoot, we decided for safety reasons to limit the number of aircraft we used. Ultimately, our sound department aided in this effort by building a comms system that allowed us to speak with the pilot of the biplane, whether that was Tom or a member of the stunt team. McQ also decided to direct Tom and Esai and survey his monitors from inside one of our pursuit helicopters; his ability to issue immediate instructions from this vantage point ensured that no crucial command was delayed in reaching any crewmember.

Throughout most of the shoot, I remained on the ground. We didn't have aperture or exposure control because that would have meant putting another aircraft up in the sky, with more tech, which would increase the level of danger on the production. By that point, we’d already formulated an exposure recipe that we could put through the grade, and the light was pretty reliable in South Africa. I worked with 1st AC Paul Wheeldon to set a specific depth of field, aperture and exposure. I didn't want a narrow depth of field. You want to read the landscape. Otherwise, why shoot it in Africa?

At Tom’s insistence, all action onscreen needed to be real and performed by him. Some shots, like the inserts of Tom's hands on the controls of the plane, would have been particularly difficult to pull off anywhere but up in the air. In the scene, the biplane performs a hammerhead-stall turn, and the natural light is directly affected by the movement of the craft: When you perform a hammerhead-turn, flying into the sun, the aircraft’s movement creates extreme shadow and light movement. It is possible to replicate that kind of look on the ground, but the approach that would require certainly wouldn't create the same feeling that our scene has. With this in mind, we rigged our Z cameras all around the cockpit for exactly these kinds of moments, and Tom would fly the biplane himself just to get the shot.

When you're going from hard light to deep shadows while shooting any moving aircraft, sometimes the light will peak too much, and our footage is imperfect — Tom goes into hot light at times, and it gets very crushed down and moody in the wing shadows. But I like that it looks imperfect. When the image goes through the extremes of exposure, it’s real.

Tiger in the Tank: Shooting the Submarine Scene

Tom’s down there alone in our extended underwater diving sequence — there are no baddies chasing him, it’s just him against the submarine. Most underwater scenes play out in slow motion, and I wanted to make sure ours was spicy, give it an edge of danger. So, we decided that since our submarine is 20 years old, it would be failing. That failure accelerates when the sub is flooded by Tom's entrance.

Every other day, we'd have a meeting we called a “war room.” All the department heads were present — special-effects people, VFX, camera, electric — and we’d discuss what McQ and Tom wanted out of the scene. We'd all throw in our problems, our positives, then we’d leave, think it all over, and come back two days later after we’d investigated. This went on throughout the shoot. It was through these “war rooms” that our stunts were built, and particularly our underwater scene. We had all the safety guys in those meetings. They would say, “No, you can't put Tom in a gimbal mount that's rotating and descending and have torpedoes falling off of the submarine.” All of the stunt work is physical — Tom won't let most of it be CG. There are odd bits that are enhanced; for instance, it might need to be half a torpedo so it won’t hit actually Tom on the head, so they’d extend the torpedo with CG. But there was still [part of] a real torpedo falling into the water, alongside collapsing shelving and more.

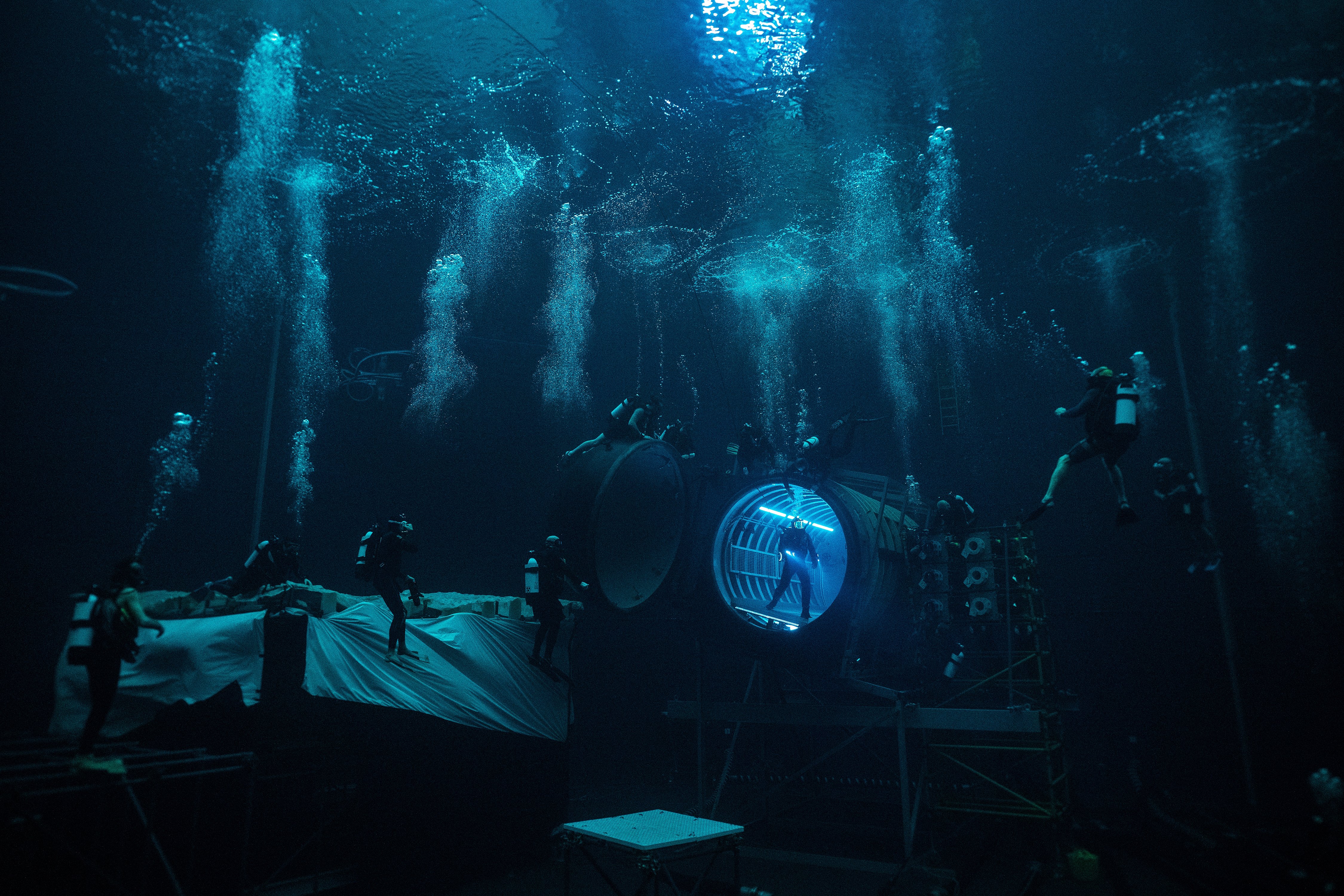

From Mexico to Malta, we scoured the world to find a suitable tank for this sequence. We could find big tanks, but the problem was that we were supposed to be 600 meters down in the ocean, so it should be pitch black. On The Abyss, they used an open-air tank and covered the surface [of the water] in black polystyrene balls to knock out the refraction. But you can’t see what the divers are doing that way. We could have shot it at night … but again, you’re adding danger to the situation. In the end, we decided there wasn't an existing tank for what we needed to do, so we built two massive tanks at Longcross Studios in England: a deep-dive tank for Tom’s descent and our exterior work around the sub, and another tank for sub interiors. In the latter, we had a mind-blowing gimbal that would pitch, roll and descend for all the flooding sequences. We tented the tanks all over and built a staged roof so we could shoot days with total control over our lighting scenarios. The tents that sat atop this roof enabled us to block all natural light that might otherwise pollute the set.

The deep-dive tank was about 40' deep by 200' across. We built a sub fuselage that was about 150' long by 20' deep. We even built real rock faces for the descent. We often put those in horizontally and had Tom on a wire so we could see more of the set either in front or behind him. With the other tank — which was about 60' deep by 160' across — 150 feet up in the air, so a whole system of sleds had to be built so we could put the different pods of the submarine into the tank for whatever action was called for that day. There were so many different effects in the gimbal! The washing-machine effect feels like a free camera with the whole set revolving around your lens. Sometimes we wanted to be mounted to the rig itself. We also used some remote heads in there for fixed cameras so we could come in and out of the water. I'd already set the lighting feel with my underwater gaffer, Martin Smith, and our underwater operator, Simon Christidis, came in for close coverage of Tom using a bespoke handheld underwater mount which he designed.

Off-the-shelf lighting for this kind of filmmaking is very limited. We had Barracudas, which are quite punchy underwater lights, and Marianas, which are probably the most powerful underwater lights but can only run underwater — we couldn’t use them in any of the gimbal rotations because if they’re dry for too long, they overheat. The rest of the lighting was built by our incredible practical sparks team, led by HOD Joe Tooke. About 90 percent of the lights we used underwater were bespoke, made by our team. There were hundreds of LEDs dressed into the set, and the whole system had to be built from scratch and battery-powered for safety. I wanted to dimmer-control it, and that had to be cabled into the system. Our practical electrician head of department, Joe Tooke, and his team devised this system, which at times stretched far beyond my understanding. When lighting is submerged for so long — with set rotations and collapses, which can occasionally endanger your cabling systems — you’re always worried about damaging equipment. For me, this was the most challenging thing about making the film. Each day, we'd do our initial early-morning tests to make sure there was nothing loose that might fall and hit the actor. Every day, I’d look at this thing and think, “It’s unbelievable this was built for a film.” I’d never seen anything like it, and I don't think I will again.

For the flare descent, we used [MBS Equipment Co.] AquaBat LED strips, which we could link together. When Tom fires the flares on his descent, we rigged all of his AquaBats and chased them down because the flares are supposed to overtake him at one point. Then, a second lot goes off that reveals the submarine. We couldn't program those AquaBats because the descent rates kept changing. So, with our desk operator, Dan Walters, we’d chase it on a manual version of the dimmer operator.

On early tests with our handheld flares, I made them amber, because I could read a good amber light when we were close to them. But if I wanted to put the amber flare 100' away for a wide shot of the sub fuselage, it’s not amber anymore because you're shooting through cool water. So, I changed the flares to a greenish-blue, which looked quite nice and mysterious in the depths. But all the flares in the previs mockup were amber, and the day before shooting the first descent, Tom and McQ said they liked the amber-flare look. I explained it wouldn’t transmit through water, but that night, we stayed for a few hours — Smith, Walters, underwater gaffer Ryan Huffer and me — and tested all sorts of gels on the camera. I added lots of amber gel to our AquaBats. We shot a test, and then I added lots of Plus Green to the same fixtures, trying to put it in a different-color window. At about 7 the next morning, I went into De Lane Lea with our colorist, Asa Shoul, and we managed to put enough green into it that we could grab it as a separate color zone. We also created another LUT so we could separate the flares from the rest of the set and dial in a load of amber for them, away from our live-grade look for the scene. It worked, much to my relief.

We tested loads of helmet designs, which had to be done quickly to allow for safety testing. (This was the same process we undertook when preparing for the Halo-jump sequence on Mission: Impossible — Fallout, on which I served as additional director of photography.) We were worried that even LED lighting can still short out and cause problems when combined with oxygen. We researched previous problems with anything near an oxygen feed with LED, and the results can be quite nasty. In the end, we built a double recess in the fascia so the LEDs weren't within the mask — they were slightly outside in a little groove. Because it's Plexiglas, there were problems with reflections; you can't use Pola screens like you can with glass. Originally, it was a three-piece mask of a similar shape. I didn't like the uprights, the window-pane supports, because it created weird angles and distorted Tom quite a lot. So, we asked to have it made out of one piece of Plexi, but molded, and that had to be researched. It was a process that took quite a few months.

I also wanted control over the lighting level in Tom's diving mask, but there was no way to do that underwater unless Tom was on a hard wire, which was out of the question because of all the action he had to perform. So, we used something called a wand, which is basically a hard cable to a sensor. If someone could get underwater with Tom and I wanted to adjust the level, we'd graduate the lights. We could adjust any of the five LED sections. So, Ryan would get in and notify Tom whenever we need to adjust the levels. Ryan would touch onto Tom's backpack with a wand, give us an OK from our observation cameras, and then Walters could quickly take control of the mask lighting to the levels we needed for the shot.

When you’re transmitting light through water, you lose so much level. If Tom starts the shot 40' away, you're losing luminance and levels, but if he travels from that point to one that’s 6' from the lens, he's too bright. I’ve heard professional divers complain that you’d never have lights in a mask, but this is a movie, and you want to see who's in the mask!

McQ wanted to be in the tank during the shoot, which isn’t typical for a director — they can use mics with underwater speakers through which all the crew can hear them. But McQ wanted to experience this with Tom, and it was the same on the plane: McQ climbed out and stood on the wing at one point. It’s a brilliant approach because it allows him to understand what Tom's going through. Tom and McQ communicated with a simple system of sign language, and one of our safety divers, with a monitor camera on McQ, would then signal instructions to the crew.

I’ve worked with Camera Revolution for years, and for our submarine shoot they designed an Aqua Libra, so we could put an underwater housing on the remote head and have a crane in there, pushing in and out and moving. I used the Venice underwater whenever I could, but if we had to get into a little corner, we used Sony’s brand new, very small Burano, and it worked brilliantly. It has the same native ISOs as the Venice, which was helpful because rebalancing any lighting scenario in the submarine was often a nightmare. The water housing is about 3’ long by the time you get your lens on, and in a confined submarine, you don't want to be 3’ away from the edge of the set. The Burano was great in that situation — I could get 10” from the wall with a wide lens on. We also used Z Cams in a lot of fixed housings because we wanted multiple cameras in there for the moment when all the debris is falling. Sometimes we'd have five, six cameras at once — some fixed, some on remote underwater heads — and Simon was in there as well doing our handheld moves.

Lots of people ask me if I think someone else will take over the role of Ethan Hunt. What other actor is going to actually do all those stunts himself? When I worked on the helicopter sequence on Fallout, I'd say to Tom, “In the frame, you’re small, we could put anyone there!” And he would say, “No, I'm the person in this film, so I'm going to do it.” That's why this franchise is so amazing: you know Tom is doing it all. I can’t imagine Mission: Impossible without him.

All images courtesy of Paramount Pictures.