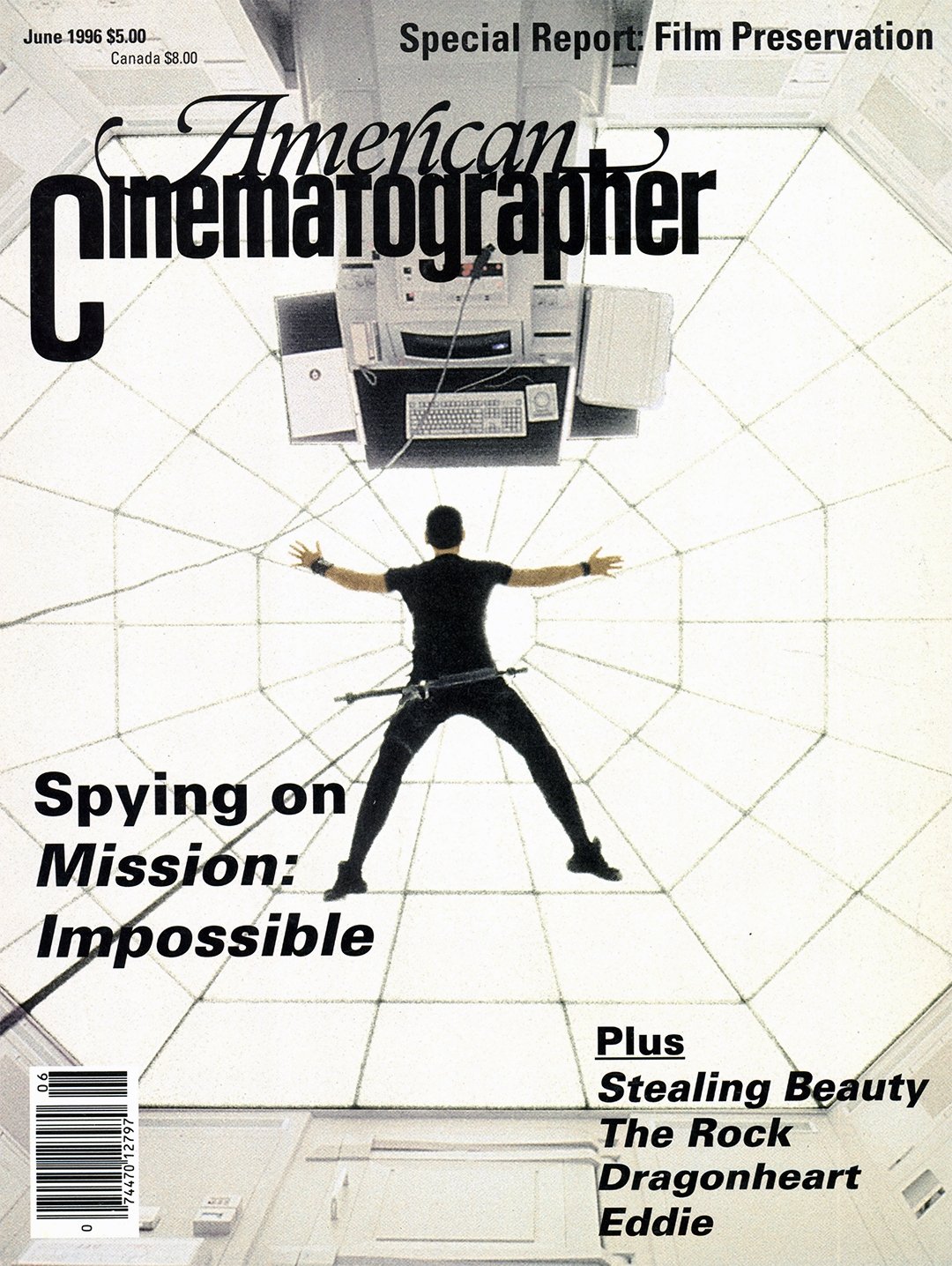

Imaging the Impossible — Mission: Impossible

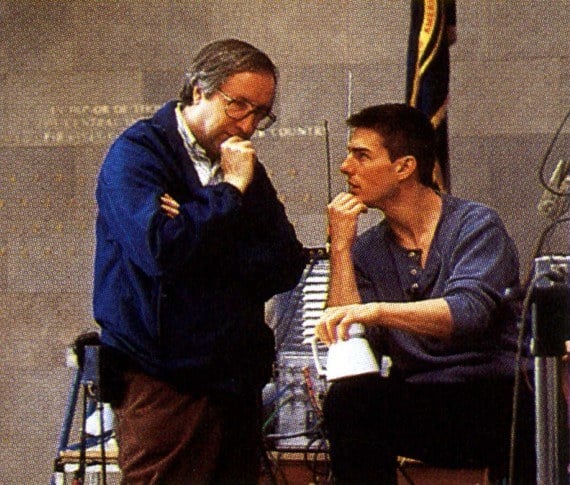

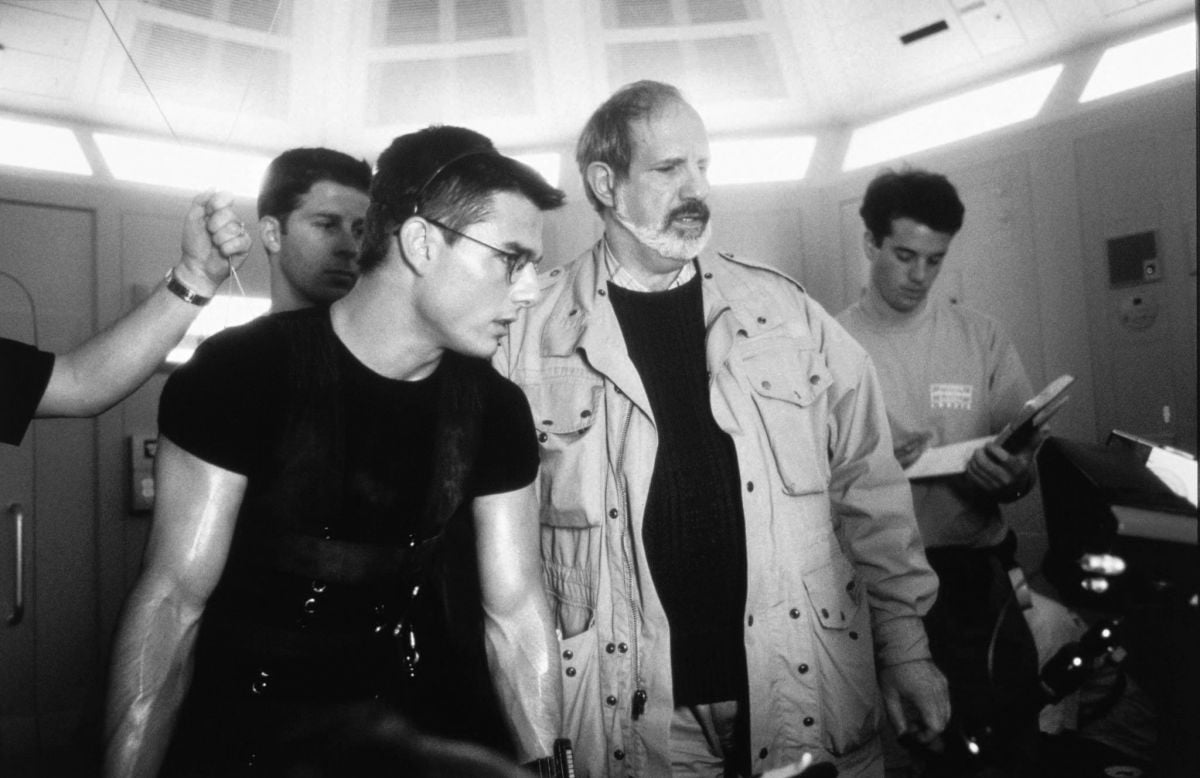

Cinematographer Stephen Burum, ASC resumes his longtime collaboration with director Brian De Palma to bring the seminal spy premise to the big screen.

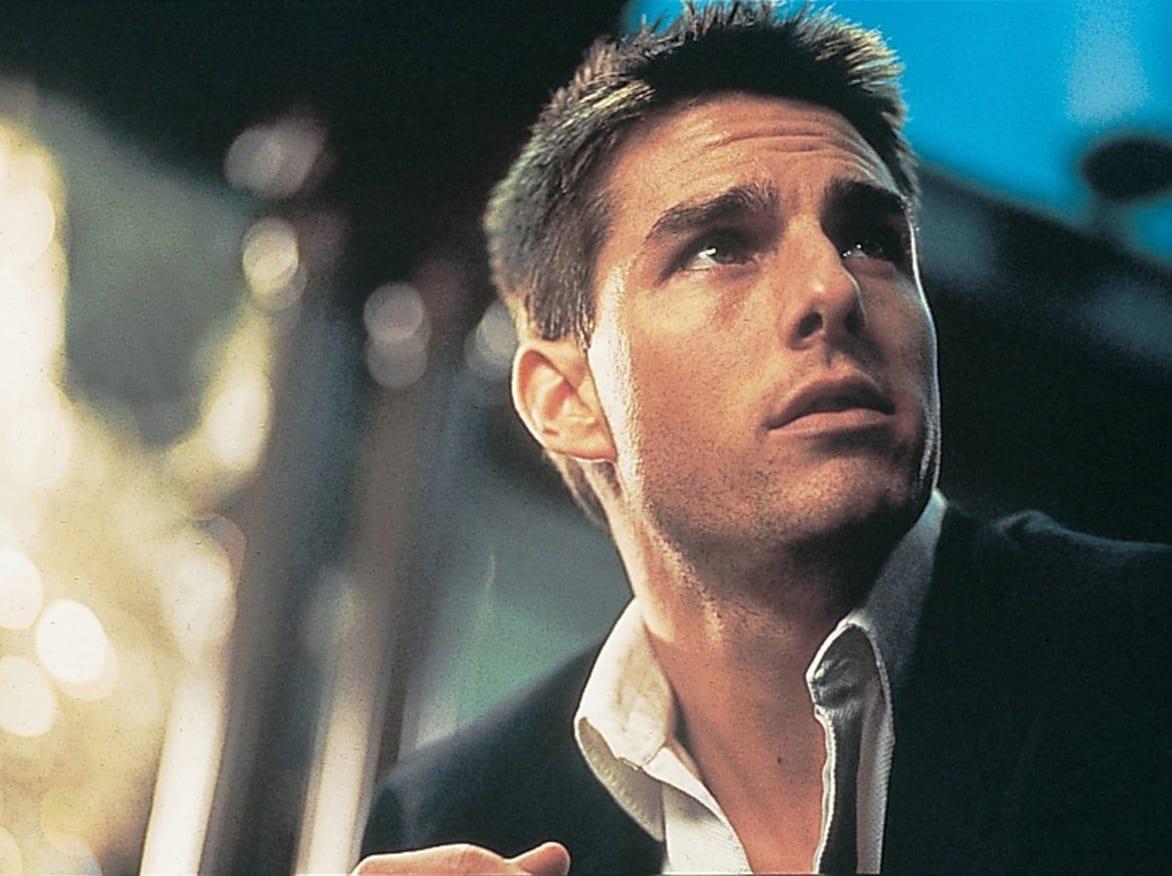

In a small darkened projection room, two men sit and watch fragments of an action movie with no soundtrack. Beaming forth from the wide-format anamorphic screen beam are powerful images of Tom Cruise, Emmanuelle Béart, Jon Voight, Kristen Scott Thomas, Emilio Esteves, Vanessa Redgrave and Jean Reno. As the actors converse, struggle, or embrace in silence, their exclusive audience exchanges a few sparse comments: “Tom’s face is a little red.” “Emmanuelle needs more blue.”

The setting for this scene is Deluxe Laboratories in Los Angeles, where Stephen H. Burum, ASC is finalizing of the answer print for Mission: Impossible with timer Denny McNeill.

After months of preparation and the frenetic production itself, the answer-print stage is a time of closure for many directors of photography, a period when they can sit back and appreciate their work. Burum likens the cinematographic process to “conducting a symphony orchestra: you’re so busy bringing in the violins, doing this and doing that, that you don’t have the real joy of listening to the music, of really feeling the music. And when you're timing and you get down to the third answer print, it hits you all of a sudden: you have the time to enjoy what you did. Until then, you just don’t.”

When timing a film, the cinematographer scrutinizes the color, brightness and quality of each individual shot, gauging its coherence against the surrounding shots in the sequence. The answer print is stricken directly from the negative; its set of yellow, cyan and magenta corrections are the foundation of an interpositive from which release prints will be produced, via the internegative. By the second or third release print, the major timing adjustments have been made, so the rest is merely a matter of fine-tuning. According to Burum, skin color is the clearest indicator for refining image quality and tone at that final stage.

“When you’re timing, you want to get a reference that will serve as a standard, so that the lab can clip it out and put it next to their timing machines,” he explains. “When there are major adjustments needed, you tend to say, ‘Let’s make it a whole lot more yellow or a lot more blue.’ Later you talk about skin tone a lot because it’s harder to define; it’s a very finicky and subtle hue.”

Mission: Impossible is based on the popular television series of the same name, which initially ran from 1966 to 1973 and was briefly resurrected in 1988 with an all-new team headed once again by actor Peter Graves’ unflappable Jim Phelps character. In each episode, the IMF (Impossible Mission Force) team had to devise and execute a plan aimed at solving some seemingly insurmountable espionage problem, such as rescuing a prisoner from an impregnable fortress. The plan always involved cutting-edge technology, elaborate disguises, split-second timing, and stealthy deception. And the danger and difficulty of the mission kept the television audience in suspense for an entire hour. The feature film version is directed by Brian De Palma, whose relationship with Burum is well established.

Over the past 12 years, the two filmmakers have collaborated on five previous features: Body Double, The Untouchables, Casualties of War, Raising Cain and Carlito’s Way. Both share an encyclopedic knowledge of cinema and a passionate enthusiasm for filmmaking. The lengthy collaboration between the duo seems a natural one, as a keen appreciation of film history informs the work of both.

De Palma is best described as a postmodern director; his films are full of references to past directors such as Eisenstein, Hitchcock and Antonioni. He knows every storytelling trick in the book, and doesn't hesitate to use them. It is telling that Quentin Tarantino cites Blow Out (shot by Vilmos Zsigmond, ASC) as his favorite film, for in many ways, the young auteur is DePalma’s heir. Critics sometimes lambast the director as a mere maker of showy homages, yet, like Tarantino, he infuses his references to past films with a very contemporary irony that creates a personal vision.

In a very different way, Burum has used his own love of the classic Hollywood tradition to enrich recent American cinematography. A master stylist, Burum has on several occasions assimilated the aesthetics of bygone genres and transformed them into original and modern imagery. Witness the highly stylized rendering of detective serials in The Shadow, or the brilliant melange of film noir and comedy in The War of the Roses. Burum's distinguished career spans from the stunning second-unit cinematography on Apocalypse Now to his masterful, Academy Award-nominated work on Hoffa. In addition, he has received ASC Award nominations for both The War of the Roses and The Untouchables, winning for Hoffa.

“Nobody does [action thrillers] better, and this project represents the best of that genre. The film was very difficult logistically, but it was finished on time and on budget, which is quite an accomplishment in itself.”

After working with De Palma on so many pictures, Burum says that he and the director speak in shorthand on the set. “I love working with Brian. He’s the greatest; he knows exactly what he’s doing. There’s not much dialogue between us on the set. [The collaboration] is not artsy at all, but very matter-of-fact. I have an expression that I use: ‘De Palma left and right.’ If Brian says the frame ends at a certain point, it’s going to end there. There is no reason to shoot anything past that point.” Burum also understands De Palma on a personal level. To an outsider, he says, “Brian may seem gruff, but he keeps all of his feelings inside.” The cameraman realized this during the shooting of Al Pacino’s death scene in Carlito’s Way, when he saw the director “with tears in his eyes.”

For viewers familiar with the TV series, the opening of Mission: Impossible is misleadingly familiar. The feature film also starts with the obligatory "self-destructing" tape of instructions, but this time the game plan is outlined on video instead of a reel-to-reel recording. An IMF team that includes the film’s hero, played by Tom Cruise, is assigned to retrieve information from the safe room of an embassy in Prague. The agents are outfitted with a host of high-tech gadgets, including explosive chewing gum and wireless video eyeglasses. Later on, there is a key sequence involving the Internet, presented in a realistic manner that is rare for today's cinema.

The embassy mission takes place during a crowded diplomatic reception and IMF operatives lurk everywhere in the building, including the elevator shaft. Much of the sequence is shot from a subjective point of view — that of an agent mingling amongst the exquisite crowd. (Burum notes that De Palma often makes succinct reference to his shots as being “either objective or POV.”) This long Steadicam shot, a vintage De Palma setup, brings the audience into the movie. Despite some harrowing moments, the mission seems successful. But the movie's tone changes abruptly with the mysterious murder of several team members in the foggy Prague night. Thus ends any similarity with the TV series.

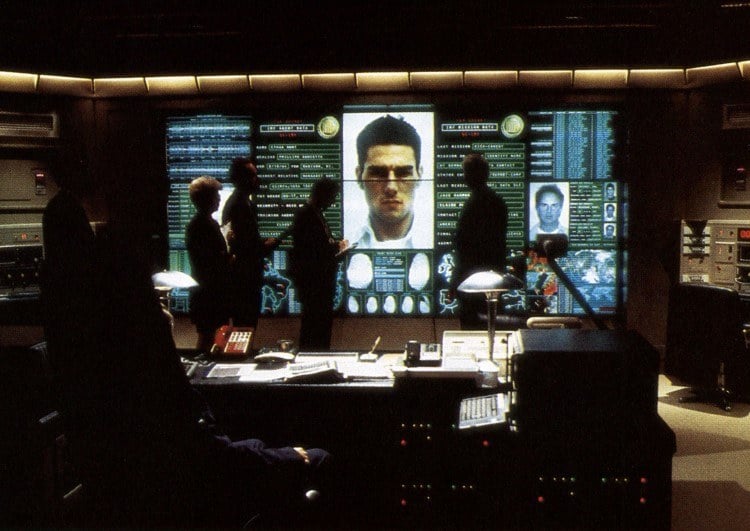

As a survivor of the failed mission, Cruise comes under suspicion but dramatically escapes capture. In an attempt to uncover the specifics behind his betrayal, Cruise organizes a renegade team to penetrate the CIA headquarters in Langley, Virginia. In a daring and suspenseful incursion into the inner sanctum of the CIA computer room, Cruise obtains information that leads to startling developments about the botched proceedings in Prague. Following a confrontational journey on the highspeed TGV train linking London to Paris, the movie culminates with a spectacular climax in the newly constructed Chunnel under the English Channel.

Burum is quick to point out that, like The Untouchables, Mission: Impossible is not a remake of a classic television series, but rather an “embroidery” of one. For the cinematographer, the appeal of Mission lies in the audience's fascination with the role of technology in espionage-related problem-solving. “The same elements that made [the premise] popular back then make it popular now. How do you solve insurmountable problems? The audience gets to ride with the spy and see all of his tricks, the high-tech gadgetry. Each character is a very skillful operator, a specialist in his field. The audience likes to see a master craftsman, somebody at the top of his form, whether he is a computer expert or master spy.”

In many ways, Burum's description of the IMF operatives applies to the cinematographer and his collaborators; students of cinema enjoy seeing accomplished filmmakers solve storytelling problems with elegance. Viewers will relish the inventive and sophisticated camera movements and angles devised by Burum and De Palma. One can almost imagine someone saying to the cinematographer many months ago, “Your mission, should you choose to accept it, is to light the entire city of Prague at night, and you have three weeks to do it.”

Like an IMF mission, the production of the film was a race against time, shooting on location in Prague and London, and on sets built within the vast Pinewood Studios soundstages. However, the film's British production designer, Norman Reynolds, notes that the film's European locales merely enhance its essential spirit. "Mission: Impossible is an American action film, in the best sense of the term," he says.

Reynolds, who earned two Oscars for his memorable design work on Star Wars and Raiders of the Lost Ark, is well-positioned to comment on the relationship between the production designer and the cinematographer. “The designer [helps to set] the picture's tone in visual terms. Now that's apart from the cameraman, who obviously has the ultimate control in that area, because he can make it dark, light, colored or whatever. So what we designers do is very much in the hands of cameramen. I certainly stay in touch with the cameraman as much as I possibly can.

“While we were in Prague, Steve was obviously very involved in location scouting and preparing things, so there were times when he and I were separated. But when we moved to the studio, I involved Steve as much as possible in the set design. It was quite selfish really, because the easier I made Steve's job, the better the film was going to look. We liked working together, and that's really the name of the game."

In planning their visual design, Burum and Reynolds referred solely to the script and not at all to the television series. In fact, Burum confesses to having never really watched the TV show. "I remember a little from college, but I never got a chance to see an entire episode," he admits.

Following the natural divisions of the script, Burum created a different lighting approach for the missions in Prague, Virginia, and on the TGV train, producing a visual diversity and rhythm that enriches the film. The cinematographer summarizes the three moods he sought to evoke as "old Europe, America and new Europe."

In Prague, Burum sought to create an atmosphere that evoked "the old European spymaster stuff. You know, the spymaster slinking around, dining in chic restaurants, smoking cigars and drinking brandy, while some Eurasian woman is wearing a tight silk dress with a mink dropping off her shoulder, with a Twenties bob hairdo — the Mata Hari thing. Here you are in Prague, which has just been freed from the Communists and is still mysterious, almost Oriental. Anything can happen, and of course, all kinds of nefarious devious stuff is going on because everyone is grappling for power, and everything is up for grabs."

In lieu of Mata Hari, Mission: Impossible features French actress Emmanuelle Béart as Claire, an IMF member and romantic interest of Hunt’s. To give Béart a "more ethereal" appearance, Burum chose his customary black silk stocking diffusion when shooting her close-ups. Onscreen, the diffusion is subtle and Béart's face still looks sharp. The cinematographer explains that "women, even when heavily diffused, don't appear diffused on film because their makeup accents their eyebrows, eyelashes and lips, which gives you a false sense of sharpness. For example, normal lip color blends in with the face but, with lipstick and liner, the lips look a lot sharper than they really are."

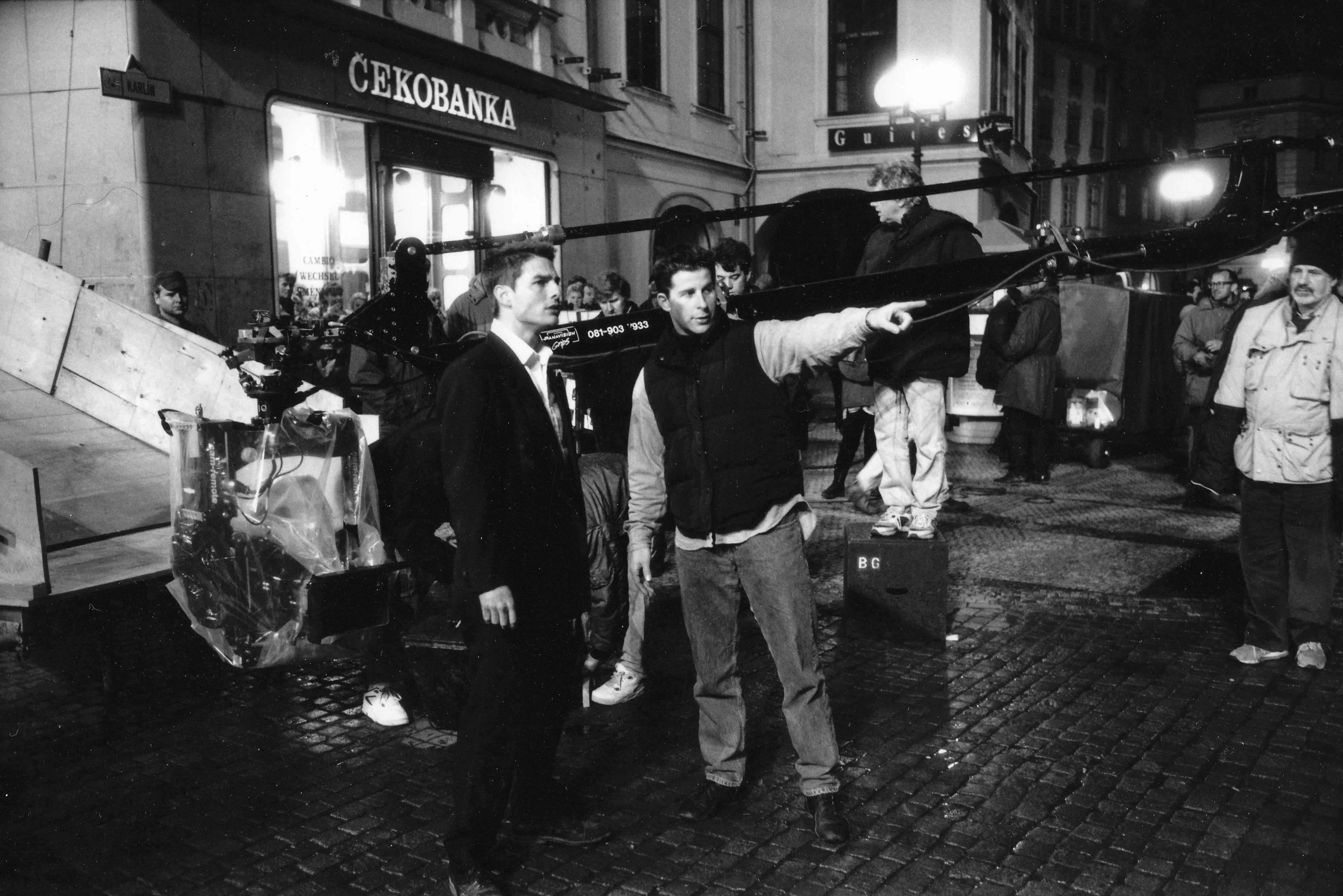

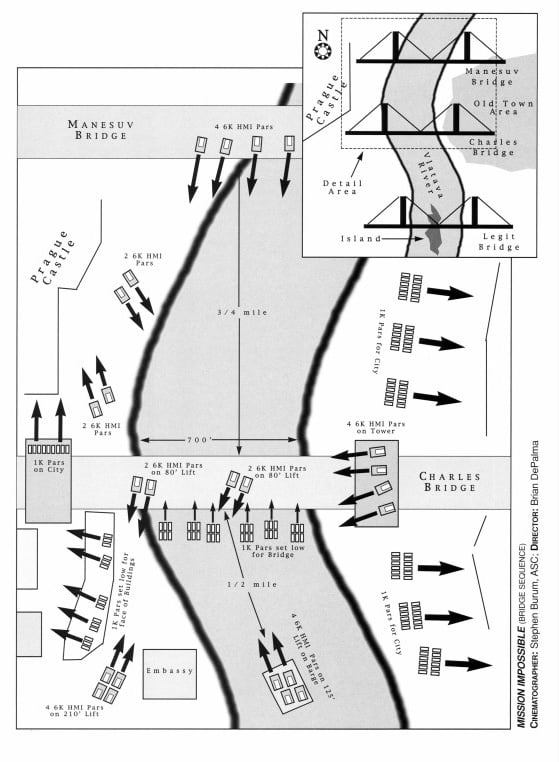

Most of the "old Europe" sequences in Prague take place at night. From the look of the film, the crew had the run of the Czech capital. The venerable but run-down Natural History Museum posed as the embassy's reception hall. Key exteriors were shot in Prague's two prime tourist spots: the beautiful square at the center of the old town and the famous Charles Bridge. These picturesque nightscapes required an excessive amount of light, since Mission was shot in the anamorphic format. For Burum, the lens T-stop setting is an essential factor in the quality of widescreen images.

"Many people ask me why my anamorphic shows look so sharp. It's because I know which stop to put the lenses at. You can't get an anamorphic lens below T4 and keep it sharp. In desperate situations, I have shot scenes at T2.8. I've been able to get away with it because I light very hard and very contrasty, which gives the images a phony sharpness. But if you try to light an anamorphic image at T2.8 with a soft light, the image will have no snap." Rawdon Hayne, Burum's 1st camera assistant, was instrumental in this endeavor.

Burum used Panavision's C-series anamorphic lenses, which he prefers to the E series because of their small size. "There's something about the older lens design that gives the appearance of a bit more depth of field. In point of fact, the term depth of field is baloney; there is only one point of absolute focus. Everything in front and everything behind is not really in focus, but rather seems to be in focus to your eye. If you have a lens that is ultra-sharp or heavily contrasted, then you see that difference in focus immediately. Older lenses are not quite as sharp, so they only appear to have more depth of field."

Burum chose Eastman Kodak's 5298 stock for the entire film. Its speed facilitated the lighting of night exteriors and dim daytime exteriors in Northern Europe and gave a healthy T-stop for the anamorphic format. Says Burum, "I usually rate 98 at 500, but for Rank in London, I rated it at 400, because there was a difference in their processing." The cinematographer used the English lab for rushes, and its Los Angeles sister lab, Deluxe, for the answer and release prints.

Even with 5298, lighting Prague by night for a T4 was a gargantuan effort. Recalls the cinematographer, "We had to light two miles of riverfront on either side of the bridge. We ended up carefully placing 450 IK Par lights to duplicate the architectural lighting."

Burum complemented this army of small units with two kinds of bigger fixtures he first discovered in Europe: a 6K HMI Par developed by LTM, and a variation of a balloon light invented at a small French company called Publux. The 6K HMI unit houses its bulb in a parabolic reflector that permits a minimum of flooding and spotting control, thus enabling the cinematographer to throw light onto the Charles Bridge from an¬ other bridge and a river barge, from distances of a half a mile away or more. The concept behind the light balloon, like many brilliant ideas, is disarmingly simple. Translucent material is filled with helium and fixtures for quartz lights. Let the balloon float to the desired height, turn it on and voila: instant soft lighting. Burum wanted more wattage than the original 4K Publux balloons offered, but the company was unable to deliver it, so the cinematographer asked Ronny Pierce of Lee Electric in London to build four 8K models that hovered over the Charles Bridge. Burum notes that the balloons also came in handy when lighting the stairwell of an interior location in the elegant Europa hotel.

Of course, all of these 1K Pars, 6K HMI Pars and 8K balloons had to be rigged, powered and positioned. Add a lighting barge, 200- foot platforms and industrial-strength smoke machines to create a fog effect in already adverse weather, and it becomes apparent that the cinematographer had no reason to envy a Cecil B. DeMille production.

“There were a couple of nights when we only got two or three shots because it snowed, and then it rained very hard, which ate the fog. After that, there was strong wind, and the fog didn’t stay. We went against every ounce of common sense, but we persevered and succeeded. We came out about a day ahead of schedule.”

"It took us three nights to set the lights, and we had 20 walkie-talkies for the electrical department alone," he recalls. The cinematographer's invaluable right-hand man in the massive effort was gaffer Laurie Shane.

One unintended result of this logistical feat is that the next generation of tourists will buy postcards that could conceivably be captioned, "Nighttime Prague, lit by Stephen Burum, ASC." With a smile, the cinematographer remembers, "All of the postcard photographers were out, and they couldn't believe their luck; they never had never seen such a well-lit nightscape."

Unfortunately, for the sake of the Mission: Impossible story, "a lot of the footage was left on the cutting room floor," but the nighttime footage that remains in the picture is richly mysterious. As the blundered mission unravels, the disoriented IMF members wander in a dangerous fog. The HMIs set an overall blue ambient light, punctuated by white from quartz sources and keen yellows to mimic sodium-vapor lamps. Burum had the characters wear dark coats to keep a black reference in the diffused blue fog. "Fog varies a lot: sometimes you can see through it, sometimes you can't. What I tried to do was to layer light and dark areas in the fog — like Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde or Owen Roizman [ASC's] work in The Exorcist."

After the mishap in eastern Europe, the film's action moves to the CIA headquarters in Langley, Virginia. The building's bright and sunny interior is a striking contrast to the moody Prague night scenes. Burum eschews the cliché that well-lit scenes are less dramatic than dark ones. "Lighting a scene brightly, with a high degree of visibility, sometimes means avoiding a tacky choice. For example, Gordon Willis [ASC] did a wonderful 'high visibility' suspenseful picture, All the President's Men, using fluorescents to create a very natural lighting. We all love to do Vermeer, but it's not always appropriate. There is a great difference in light between Northern Europe and the United States, so I used a very soft wrap-around light for the European stuff, and I purposely used bright sunshine with shafts of light coming through the window for the American sequence. I used very hard light to create shadows, though I did cut it off above the neck so that the faces were in a softer light."

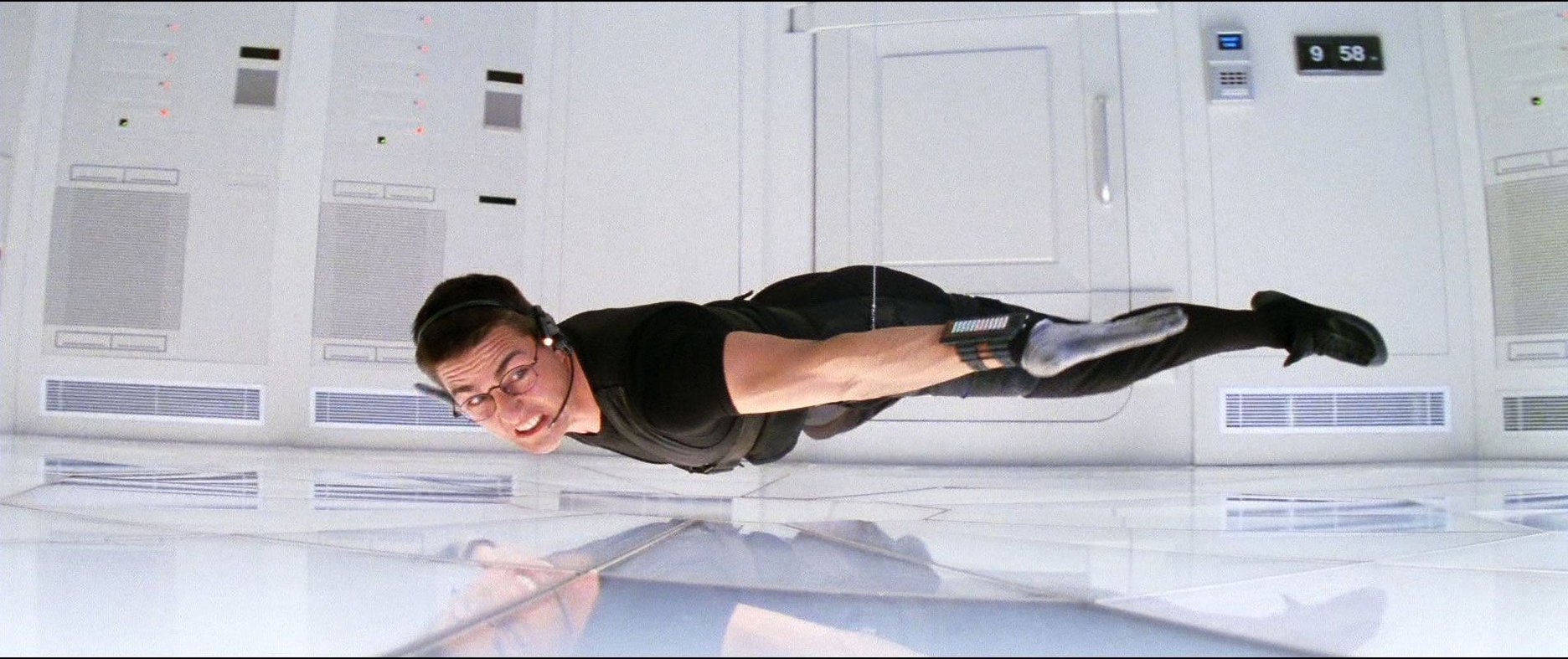

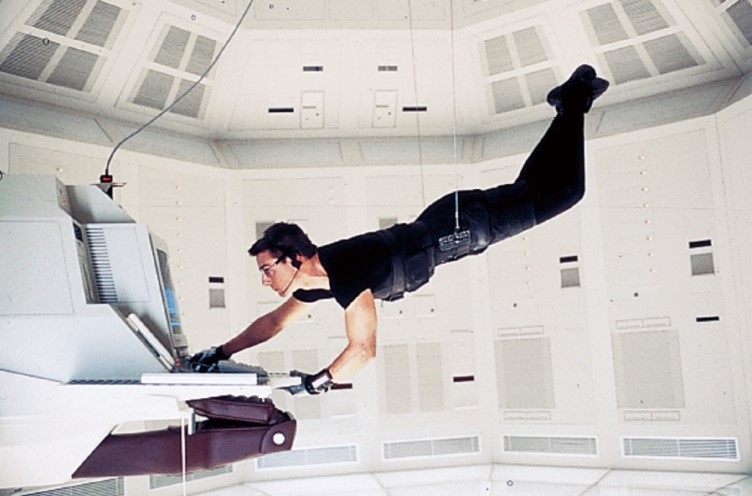

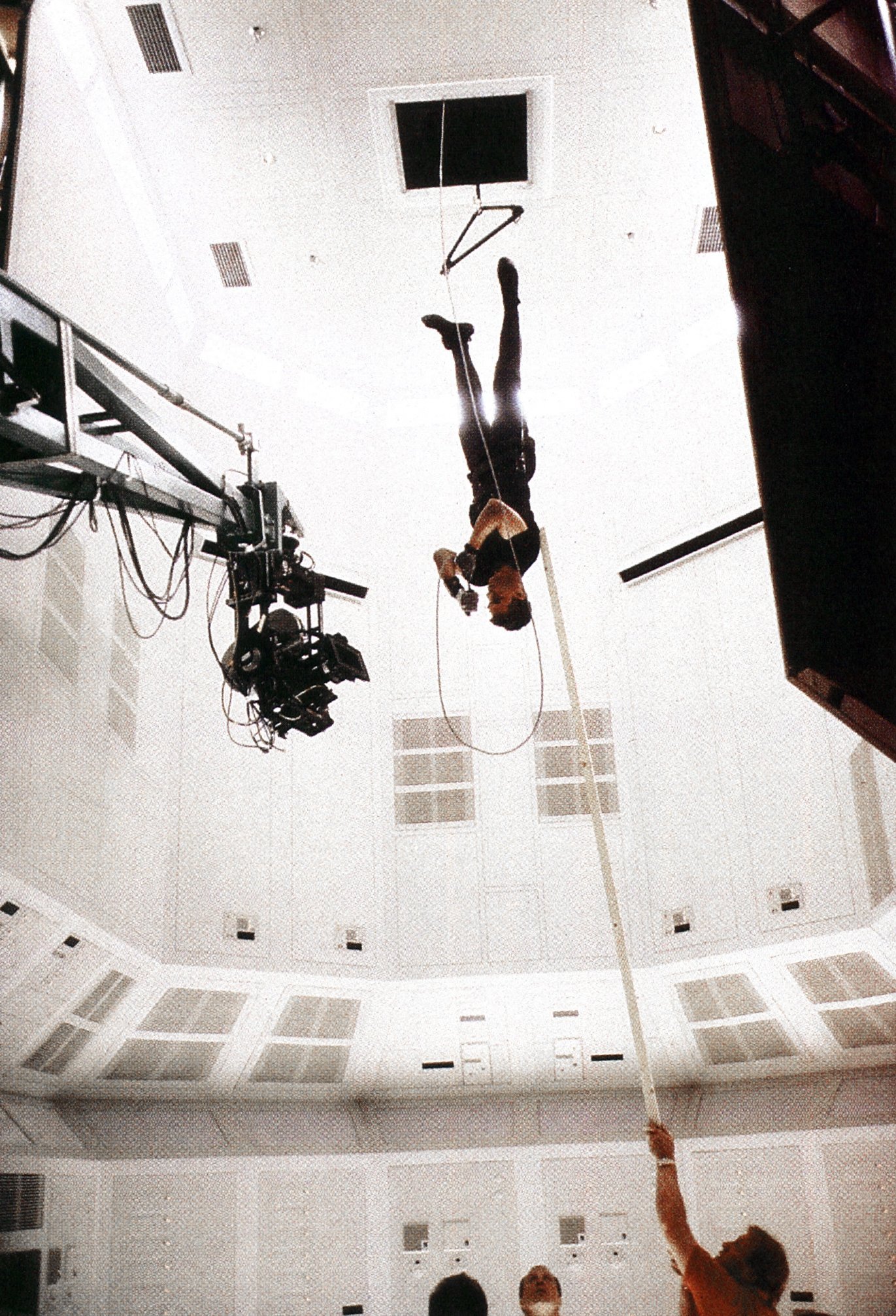

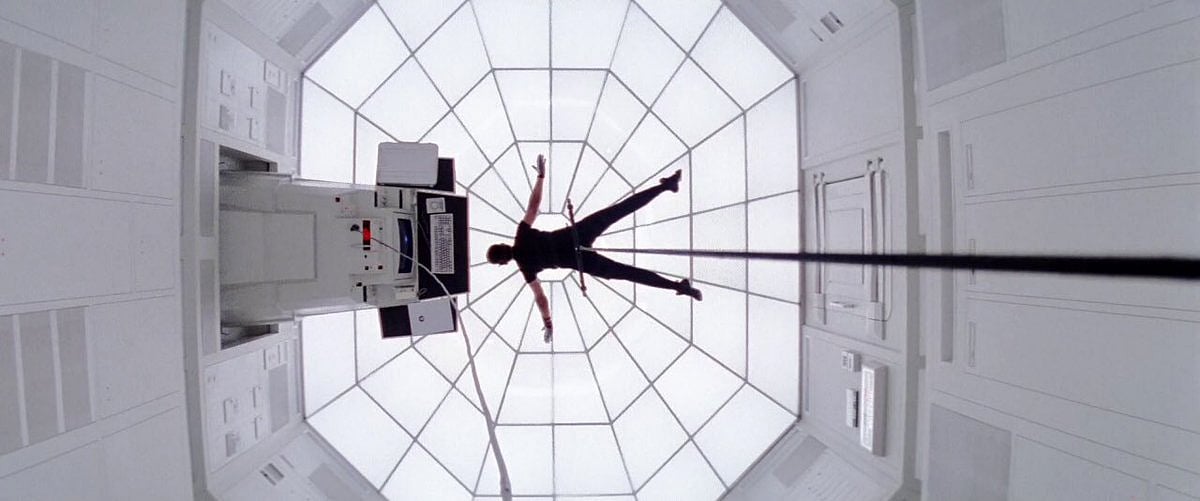

Burum goes on to prove that, paradoxically, a "brightly lit" image can sometimes create more drama than a dark one. Such is the case with a highly suspenseful scene in which Cruise's character attempts a daring daytime break-in of the CIA computer room, suspending himself by a rope dangling from a ventilation shaft. "I could have made the inside of that computer room dark and mysterious, with silhouettes; it's a choice. But it's much more intense if you can see everything, because the hero is completely exposed, and has to do his magic out in the open. It enhances the suspense if you can see everything; there's no place to hide, and the hero is a dead duck if someone walks through the door."

The high-tech CIA computer room set is a good example of the collaboration between production designer Reynolds and Burum. Reynolds drew his inspiration from his previous set designs in Star Wars to create a space that was also a self-contained soft light source. This futuristic white room is a seamless integration of luminescent plexiglass panels with dozens of photofloods and 216 diffusion behind them. The effect is an expanse of shadowless whiteness. To ensure the purity of the white light, Burum overexposed the panels by about three stops to "burn out any color. It's an old photographic trick: if you want to get rid of oversaturation, you overexpose, and if you want heavy saturation to get a weird color, you underexpose."

Cruise wore a black outfit to retain contrast and sharpness in the extremely soft light. Burum says that much of the suspense in Mission: Impossible was created by trapping the protagonists in confined spaces. "Throughout the picture, the characters are stuck in airplanes, in elevator shafts, in air-conditioning ducts. There's no place to hide. If you get caught in a tunnel and there's somebody coming, you have no way out — it's that feeling of being completely vulnerable at all times."

The IMF protagonists are similarly entangled in the final act of Mission, as they ride the TGV train at 80 miles an hour. Shot on a soundstage at Pinewood, the sequence used extensive bluescreen CGI (computer-generated imagery) to create the rapidly moving landscape and Chunnel walls. Burum finds nothing radical about shooting film for digital manipulation. "Everyone makes it out to be very complicated, but it's not; there's nothing to it," he maintains. "CGI is a simple matting process that happens to be done in the computer instead of with an optical printer. For the cinematographer, the technique is basically the same. Figure out the areas that you want to cut out, and place other footage in the hole you've cut."

The cinematographer adds that, when the camera is moving, CGI requires a three-dimensional reference in the frame, so that the computer model can track the camera's path. "Some people like to put in a cube with white points on it, some people cut tennis balls in half. We used big orange dots and white X's in the blue screen area. The dots or X's are connected in the computer to make wireframes, from which the computer can interpolate the camera movements. Then the other footage in the blue area can be altered accordingly." Burum credits special effects supervisor Richard Yuricich, ASC for the amazing verisimilitude of the effects on screen.

[You'll find our look at this VFX work with Industrial Light and Magic here.]

Mission: Impossible also contains some old-fashioned process shots. Towards the end of the Prague sequence, Cruise shares a ride with Vanessa Redgrave in a sedan with tinted windows. The street footage behind them is a rear-screen projection. The effect is both convincing and evocative but belongs in the "old Europe" category. On the other hand, the lighting design of the TGV interiors is Burum's interpretation of new Europe's "kind of clean modern Bauhaus feeling, only not using Bauhaus colors." The cinematographer lined a series of 10Ks on one side of the train set, all positioned at the same angle, to create a sun for each window. On the shady side of the train, 10Ks were fitted with cardboard snoots and equipped with 216 diffusion to create "a big soft wrap-around light, then we placed fluorescent tubes down the center of the train that weren't quite as bright." The colors of the train images are muted, and the light is restrained yet sunnier than the Prague footage. Visually, the effect is a marriage of the Prague softness and Virginia harshness. When the train enters the tunnel for the climactic scene, the fluorescents provide the main lighting, complemented by a flickering strobe that mimics the lights zooming by on the Chunnel walls.

Months later, after the release-print session, Burum recalls the frantic everyday pace of Mission: Impossible. "I think [it happens] to every cinematographer, especially on a big picture. You spend a lot of your time with administrative details. You're always in the thick of the battle, you're catching up, you're running this crew, you're running that crew, you're talking to the director and you're making sure that the actress feels great about the way she looks. It's as if you are constantly tweaking and maneuvering this great big machine. You have to keep turning the dials and you would like to have five whole minutes to be able to look at the setup and kind of contemplate. But that's a guilty pleasure, because as a cinematographer, you are responsible to the story, to the director, to the actors and the production company."

His mission complete, Burum looks pleased, and not the least bit guilty.

The cinematographer was honored with the ASC Lifetime Achievement Award in 2008.