No Fear: Michael Goi, ASC, ISC

The tireless professional always seeking his next creative challenge accepts the Society’s Career Achievement in Television Award.

The mantra “Don’t be afraid to fail” has served Michael Goi, ASC, ISC well in his work behind the camera on such shows as Avatar: The Last Airbender (AC July ’24), American Horror Story, Web Therapy and Glee. “That’s one of the first, most important things I learned about filmmaking,” says the recipient of the ASC’s 2025 Career Achievement in Television Award. The honor will be presented during the ASC’s annual gala on Feb. 23.

Experimental Spirit

As a student cinematographer at Columbia College in Chicago, his hometown, Goi shot more than 120 student films, and failing repeatedly in these endeavors dispelled his fear of trying new things. “Now, every job I take, I try to do something I’ve never done before,” he says. “I tell my students and mentees, ‘Throw away your first idea,’ because it’s likely something they’ve done before and feel safe with. That habit stifles creativity.”

His spirit of experimentation is inspired to a great extent by the earliest silent films, particularly those of stage magician George Méliès. “We’re just using better tools now,” says Goi, whose interest in stage magic and movies developed together. “I wanted to be a filmmaker since I was 8, making 8mm movies. By high school, I’d saved up for a 16mm Bolex camera and was making more sophisticated films around the same time I got into magic.”

“The License to Do Anything”

At 19, Goi was shooting spec commercials and working for a local Spanish television station. Then he found work as a production assistant on The Blues Brothers, “which was a chaotic first exposure to large-scale feature filmmaking. I naïvely thought, ‘If this is what Hollywood filmmaking is, maybe I can do it from here.’ So, I started shooting low-budget feature films, mostly horror.”

Goi’s interest in that genre goes back to one of his earliest movie memories: seeing the trailer for Mario Bava’s phantasmagoric giallo Blood and Black Lace. “It was at least a decade before I finally saw the film itself, but the trailer left a vivid impression and ingrained in me an appreciation for the visual aspects of horror — the shadows, the mystery, the anticipation, and these visceral, violent images coming at you in rapid succession. Horror films showed me that as a creator, you had the license to do anything.”

Later, it was Mike Nichols’ The Graduate, shot by Robert Surtees, ASC (AC Feb. ’68), that showed Goi the power of cinematography to manifest a character’s thoughts and feelings. “In horror, that approach means putting the audience inside a person’s terrifying experience. It’s the same approach I use in everything, actually. People ask, ‘What’s the difference between shooting Glee and shooting American Horror Story?’ There’s none. I get inside the characters’ heads and depict their world visually.”

From Chicago to L.A.

Goi shot his first feature, Camper Stamper (aka Moon Stalker), in 16mm over 12 days on a property near Sparks, Nevada. His first Chicago-based feature was the romantic drama Sam and Sarah. Around that time, he also co-wrote and shot the low-budget action film Chains. One of the last projects he shot before moving to Los Angeles was Hellmaster, in Detroit. “I realized I’d always be the third or fourth cinematographer hired on a film coming to Chicago. I wanted to be the lead cinematographer, and to do that, I needed to be in Los Angeles, where I could take meetings and build relationships.”

He moved to L.A. during a recession; little work was available, and many small film companies had recently gone bankrupt. At interviews, he found himself competing against ASC cinematographers, “so I knew I wasn’t going to get the job.” After six lean months, he was hired as a grip on a low-budget, martial-arts feature filming in Las Vegas. He had to pay for his own motel, which ate up his entire salary, “but at least I was on set. I brought my still cameras everywhere … [and] the producers noticed and asked if I’d take promotional shots of the action stars. Then they asked if I could operate a film camera. By that point, I’d shot over 200 commercials, six features and PBS documentaries. They put me on the D camera for a big stunt, and the footage turned out well, so they promoted me to second-unit DP, and then, on their next two low-budget action films, to principal DP.”

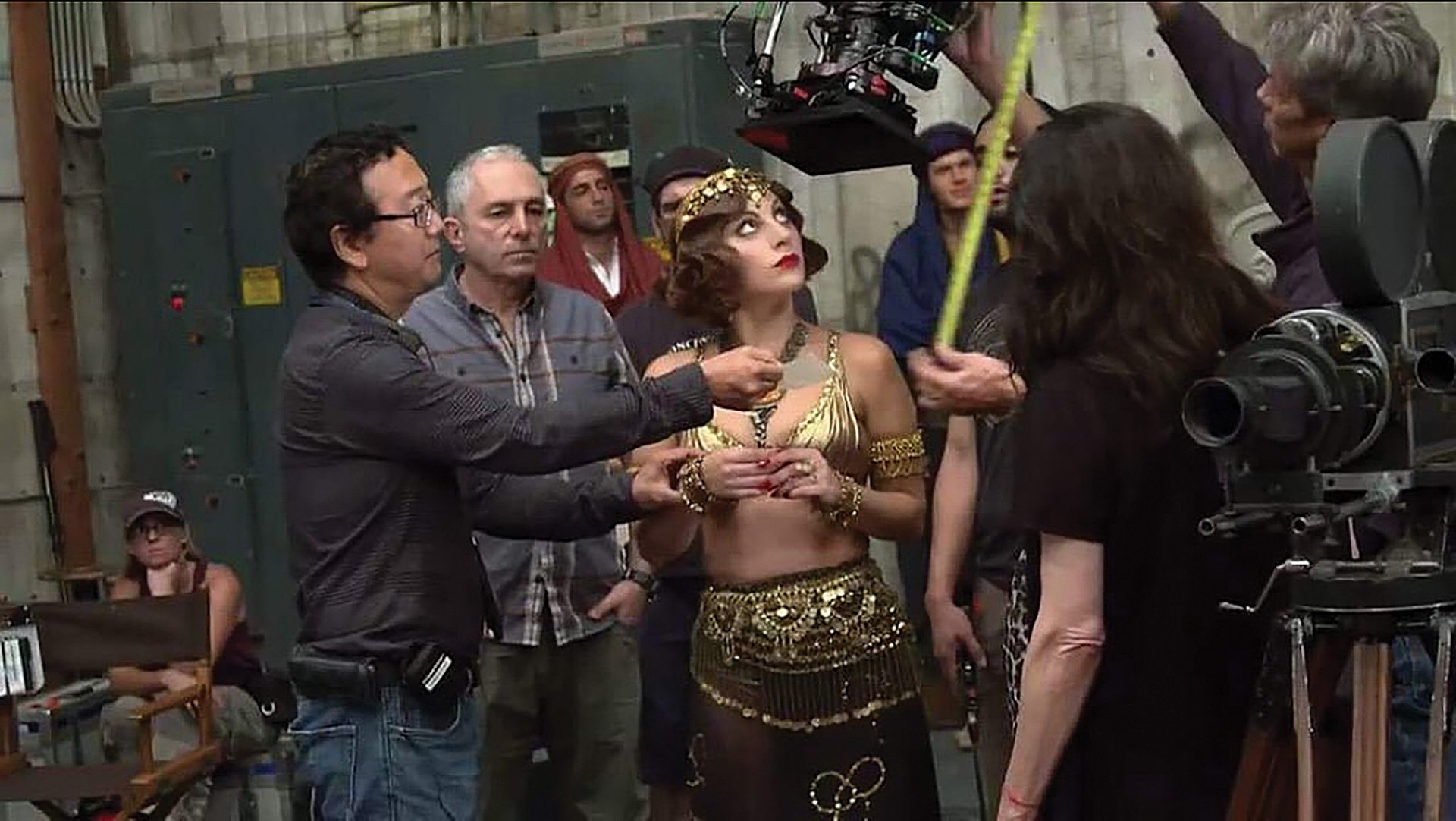

At the same time, a Chicago connection put Goi in touch with Indigo Productions, which was creating content for Playboy TV. Because the same crew worked on all Indigo projects, it took two years for the contact to pay off, but it did: Indigo hired Goi for a 10-day shoot when their regular cinematographer wasn’t available. “They liked my work, and after that, I became their regular shooter, which led to work with MRG Entertainment, who produced erotica for Cinemax and Showtime,” recalls Goi. “Shooting all those shows taught me a lot about how to light women beautifully and quickly, because we’d shoot a half-hour show in one 12-hour day, 75-95 setups with two 16mm cameras, covering eight sets.”

“People ask, ‘What’s the difference between shooting Glee and shooting American Horror Story?’ There’s none. I get inside the characters’ heads and depict their world visually.”

Embracing Opportunity

Throughout the 1990s, Goi continued working on urban dramas and martial-arts films, which rose and fell in popularity. “I always had work because I’d built relationships with different companies,” he says. Eventually, he started getting hired onto more prestigious projects. “One of those was The Fixer, for Showtime, starring Jon Voight and directed by Charlie Carner, a college friend. That project earned me an ASC Award nomination [AC May ’99], which changed peoples’ perception of me as a cinematographer.”

Goi notes that although the aspirational “artist” may be compelled to only pursue mainstream projects that garner respect, “the reality is that shooting and directing films and TV is a job, and I don’t always have the luxury of turning down work just because it’s not glamorous. I often think of something Tommy Lee Jones once said when asked why he did so many crappy exploitation movies in the 1970s. He said, ‘I was never a waiter, truck driver or factory worker. I was always acting because I’m an actor.’ I feel the same way. It’s not always the most technically skilled person who succeeds, but rather the one who embraces opportunities. Once I agree to a job, I find ways to bring artistry into it.”

Goi joined Local 600 in 1996, and he soon began delivering lighting seminars around the country, encouraged by Local 600 National President George Spiro Dibie, ASC. “George said, ‘Talking about your work will help make you more recognizable,’ and he was right. Thanks to him, I gained visibility, often from people who attended my seminars. After The Fixer was nominated for an ASC Award in 1999, I was proposed for ASC membership, and George was my primary sponsor, along with Richard Crudo [ASC].” The action film Red Water, directed by Carner, was the first project to feature Goi’s ASC credit onscreen.

“Do What the Story is Telling You to Do”

Goi made the most of the itinerant lifestyle that came with doing indie films and TV movies, but he also wanted to settle down and have a family. Because most TV production was in L.A., he reasoned that could offer him a more stable life, but there was one problem: “No one would hire me.” Then, in 2006, another college friend, Jeffrey Jur, ASC, recommended Goi for additional-cinematography duties on the Warner Bros. sci-fi series Invasion. Incredibly, production refused, citing a “lack of TV credits.”

“At the time, my credits were mostly made-for-TV movies and Playboy productions, which they didn’t consider real television because it wasn’t a series,” says Goi. “They felt series work had different demands and pressures. But Jeff insisted I knew the show’s style, and to appease him, they gave me five scenes to shoot one night.”

When Goi reported to set, he still hadn’t seen any footage from the show, so he asked Jur to describe the visual style. “Jeff reminded me of something he’d told me years earlier, when I worked as his electrician on a student film at Columbia College. I’d asked him what he wanted for the next scene, and he said, ‘You read American Cinematographer; you have the script; just do what the story is telling you to do.’”

With that guidance in mind, Goi shot the five scenes, and the results were so impressive the producers hired him as an additional cinematographer for another 15 episodes — and co-cinematographer for the final episode of the season/series.

Meeting Murphy

Though Invasion was short-lived, working on it opened doors. Goi started shooting such shows as My Name Is Earl, a single-camera, half-hour comedy shot on 35mm. “Because it was a comedy, people suddenly assumed I was doing multi-cam, which I’ve actually never done,” he notes. He decided not to return for Earl’s next season, opting instead for ABC Family’s The Nine Lives of Chloe King, a one-hour drama about a 16-year-old girl with supernatural powers. “Most of the show took place at night, with lots of action scenes and heroics, all shot quickly on a seven-day schedule. ABC Family was doing 10-episode seasons, which was unusual then, but is now the norm.”

Because production on Chloe King ended earlier in the schedule than most other shows, Goi was available for an interview with producer Ryan Murphy, who was seeking a cinematographer to alternate with Christopher Baffa, ASC on the third season of Glee. “The interview was brief — about 50 seconds — and they hired me on the spot,” Goi recalls. Some time later, he was halfway through shooting a musical number for the show when he was literally pulled off the set for a meeting with the producers. Expecting the worst, he was instead invited by Murphy to shoot the second half of American Horror Story’s first season.

After wrapping that, Murphy asked Goi what he wanted to do next: Glee Season 4 or American Horror Story Season 2. The cinematographer recalls, “I loved Glee, and shooting musical numbers was ideal for me — I grew up on MGM musicals, Vincente Minnelli’s work, and Cabaret and All That Jazz. But I told Ryan that Horror Story was a show that needed me more, and he agreed.”

“Embrace new things, and don’t be afraid to fail.”

Running the Asylum

Goi describes AHS as a show with many moving parts, including high-caliber, award-winning actors. “Some directors felt uncomfortable working with such big names, or hesitated to approach the visual style the show demanded. I saw that I could help with that process. Plus, I work very fast and rarely use more than three lights in a scene, which streamlined production. I could get it done efficiently while still giving it the look and feel the material demanded.”

With AHS: Asylum, Goi was given his first opportunity to truly build the style, palette and atmosphere of a series from the ground up. “I’d started implementing some of my ideas in the last two or three episodes of Season 1, but in Season 2, I went all out to create the look and feel I felt the show needed. That resonated with audiences, and the show became what it is today.”

Over the course of AHS’s first five seasons, the industry’s perception of Goi and his work changed once more. “Suddenly, I wasn’t just ‘the fast DP,’ I was ‘the artistic cinematographer.’ I credit Ryan Murphy and [AHS co-creator] Brad Falchuk for that, because they gave me complete artistic freedom to translate the images in my head directly onto film, and my gaffer John Magallon.”

Establishing a close relationship with actors helps Goi with this process, since his work depends on understanding what the characters are thinking or feeling at any given moment. “When you’re lighting and shooting a scene, there’s a technical roadmap, but with actors, you don’t always know what they’ll do with a script in rehearsal, and that unpredictability keeps things fresh.” Whether he’s working with Gary Oldman, Lady Gaga or Jessica Lange — or a day player with five lines — Goi is always open to changing his plans if the actor’s approach sparks a better idea.

Goi’s rapport with actors and efficient working style led to an invitation to direct an episode of AHS: Freak Show, the show’s fourth season. The following season, Goi directed two more episodes, and by Season 6, he made the transition to full-time series director. “Honestly, the most enjoyable part of working on the show for me was being the cinematographer,” he admits. But once he transitioned into directing, he decided to further prepare by applying to the Warner Bros. Directors Workshop.

“They were surprised that I’d applied since I’d shot so much for them already,” he recalls. “But I insisted on going through the training pipeline to learn the studio’s way. They put me in the course, and I immediately started getting calls to direct shows like Pretty Little Liars, Famous in Love and Shadowhunters.” Fox, where Goi spent much of the last six years as cinematographer on all of Ryan Murphy and Brad Falchuk’s shows, also reached out with directing opportunities.

“Major studios are merging, and the streaming services are

consolidating, leading to fewer productions, but many of the most

innovative ideas are now coming from TV.”

Seeing Through Sea Changes

Goi was accepted into the Society in 2003, sponsored by ASC members Richard Crudo, George Spiro Dibie and Stephen Lighthill.

The production landscape has evolved dramatically since he first arrived in Hollywood 30 years ago. “We’re in a period of contraction now,” Goi observes. “Major studios are merging, and the streaming services are consolidating, leading to fewer productions, but many of the most innovative ideas are now coming from TV.

“In another year, I think we’ll have a clearer picture of the new paradigm for film and TV production. Money is definitely a driving force — studios want smaller budgets and tighter schedules — but every studio, network and production company is also looking for content that stands out, something iconic that grabs the public’s attention. It’ll be an exciting time for creative people with unique perspectives. Stories that reflect diverse cultures and viewpoints will thrive if they find a champion in the industry who believes they’ll resonate with the public.”

Goi is excited to be part of the evolution, and as chair of the ASC’s Artificial Intelligence Committee, he has some perspective on what lies ahead. “Whenever a new technology emerges in the film industry, it drives a demand for those who can navigate it and use it. If you approach it with a willingness to learn, you’ll evolve along with the industry. Embrace new things, and don’t be afraid to fail.”

Further Reading