Lifelong Lessons: ASC Master Class

Personal passions and varied perspectives enrich the Society’s ongoing program, which offers education and inspiration in equal measure.

All photos by Danyael M. Alcaraz for the ASC unless otherwise noted

From the latest virtual-production tools and methods, to the basics of portraiture lighting, to subverting “technical perfection” through unconventional means, the subjects taught in the ASC Master Class cover a wide gamut.

And that reflects the instructors themselves.

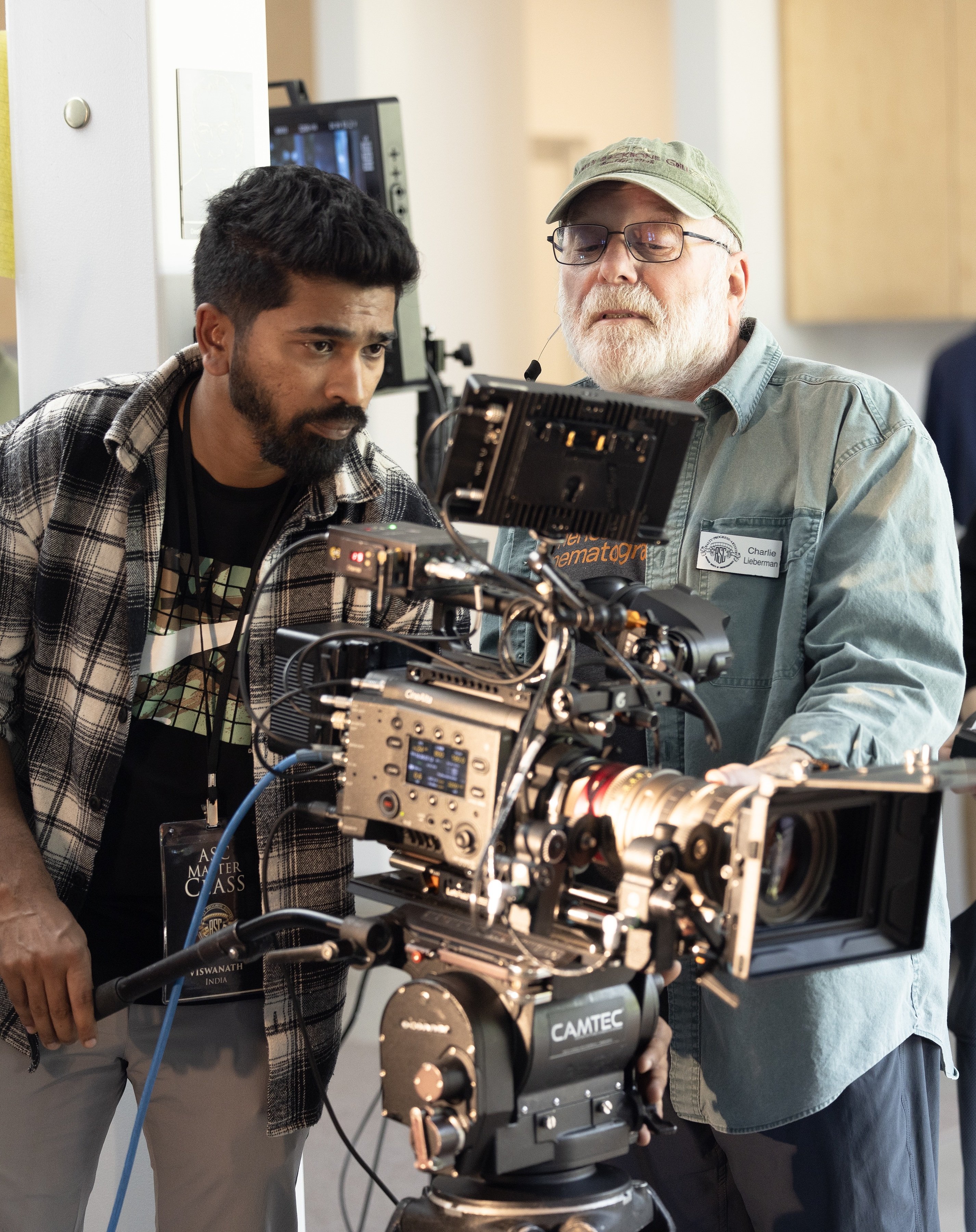

“The depth of our curriculum is the result of our members who teach,” says Charlie Lieberman, ASC — who serves as co-chair of the Master Class Committee with ASC President Shelly Johnson and Society members Michael Goi and Craig Kief.

“The quality of Master Class is all about the people who teach it, and that’s a reflection of the ASC as well.”

— Charlie Lieberman, ASC

In curating each session, Lieberman and Johnson strive to offer a wide range of experiences and perspectives. “The instructors are all very distinct individuals and artists, and each bases their respective lessons on what they personally feel is important or interesting and speaks from their on-set experiences, so it’s virtually impossible that any two instructors are going to cover the same topic the same way,” says Lieberman. “That’s the strength of our program: It’s always surprising — even to us — and things go in directions we never would have anticipated.”

ASC members who have recently volunteered to teach in the Master Class program include Natasha Braier, Alice Brooks, Vance Burberry, Steven Fierberg, Steve Gainer, Tommy Maddox-Upshaw, Sam McCurdy, Boris Mojsovski, Michael M. Pessah, Wally Pfister, Christopher Probst, Newton Thomas Sigel, David Stockton, Roy H. Wagner, Mandy Walker and Robert D. Yeoman. Each devised a unique lesson plan.

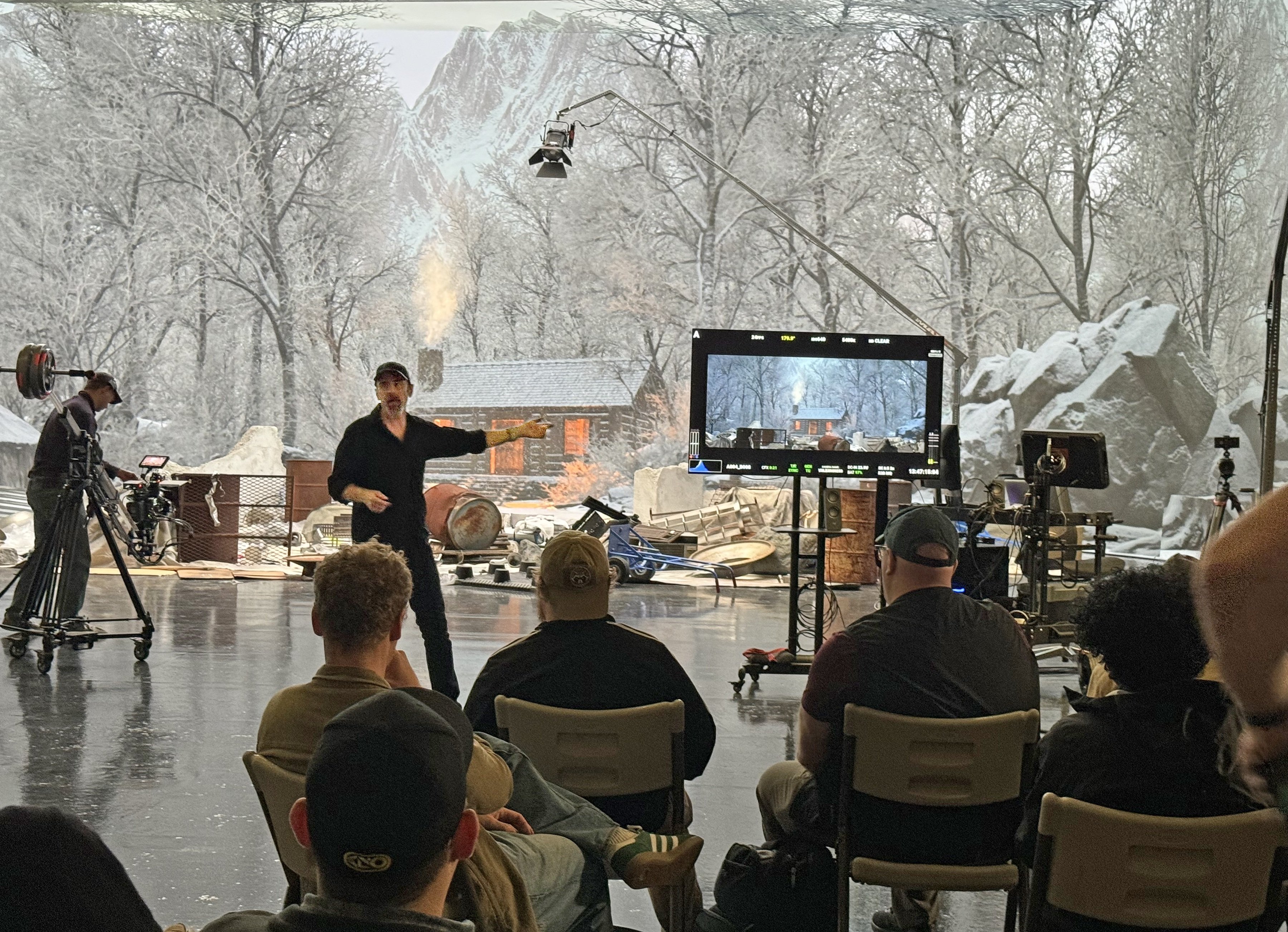

“For most of the class participants, this was the first time they had been on a virtual-production stage, and that can be overwhelming.”

— Christopher Probst, ASC

For a recent seminar on virtual production, Probst leaned into his long history as an educator, which includes writing and editing for American Cinematographer, teaching at the Global Cinematography Institute, and co-authoring The Cine Lens Manual (2022) with ASC associate Jay Holben. Probst’s session was hosted by Synapse Virtual Production, an L.A. company in which he is a partner.

“Making sure the class was a success was all about the prep,” he says. “It was three weeks of breaking down the process we use here and creating a PowerPoint presentation that would serve as a reference for the whole day.

“For most of the class participants, this was the first time they had been on a virtual-production stage, and that can be overwhelming, but I took that into account in my prep, so the PowerPoint walked through every element of the process and defined all our terms. That allowed the class to really focus in the moment to absorb the demo and then later mentally walk their way back through it.”

Also key was Probst’s use of professional-quality virtual assets combined with screen-ready physical props and set pieces that had been created for a prior Synapse production. He explains, “The concept of virtual production can be much more easily absorbed if you’re teaching with assets that truly look convincing when they come together in the camera and you see the effect on the monitor.

“Often, demos are done with pretty simplistic assets that never look quite right — because that’s what they have — and, as a teacher, you’re fighting that because the illusion doesn’t really work,” he continues. “I didn’t want to have to ask the class to ‘fill in the gaps,’ so to speak. And because I’m a partner here, I could really optimize everything with our facility and team. So, for example, as I was explaining something in response to a question, you could see — in real time — changes to the screens to support what I was discussing or describing. That helped make everything work smoothly, which also helps the teaching process, and I think our class appreciated that.”

“I don’t want my images to look ‘perfect,’ but rather to tell us something about the emotion of the scene or our characters and accentuate that in a visual way.”

— Natasha Braier, ASC, ADF

Braier, who recently taught her first two ASC sessions, says she “was so grateful” to have the opportunity to volunteer. “I had been approached many times before,” she notes, “but my schedule just had not cooperated. The stars finally aligned!”

With teaching experience at the AFI Conservatory and the National Film School in London, among other places, Braier was experienced in designing a lesson plan, but the ASC Master Class posed a unique challenge: “It is unlike a traditional film school setting, as each teacher is only given, at most, one day out of a five-day session schedule, so you must be concise in your concept.

“In my class,” she continues, “I wanted to connect with my early years as a still photographer working in the darkroom to create images that were less naturalistic and more expressionistic. That’s something I carried over [into my work] as a cinematographer. I don’t want my images to look ‘perfect,’ but rather to tell us something about the emotion of the scene or our characters and accentuate that in a visual way. I describe it as ‘destroying’ the perfectness of the clean digital image, or ‘f---ing it up.’ I want to move toward impressionistic poetry rather than just representation of my subject.”

Braier walked her class through some of the methods she has used to accomplish this, unpacking boxes of fabric, glass beads and other materials that she uses in front of the lens to affect the image by creating streak, flare and focus effects in-camera. “On films, this is a creative journey that started on my first shorts and continues today. I want to dirty up reality and add layers of subjectivity and expressionism. I want the digital image to feel more like film — or at least more organic.

“I choose my feature projects and directors very carefully, as I am trying to build a body of work that represents my vision,” she adds. “I choose to not compromise on that. The commitment to shooting a feature is all encompassing, so I must be 100-percent engaged, and the director must be as committed to the look we agree upon. Starting out in their careers, some [cinematographers] will say yes to shooting at every opportunity to gain experience, and that’s one pathway. But you’re building a body of work that you will be known for, so I choose to curate that very carefully; it represents me as an artist, and people will know what I might bring to a production. Meanwhile, I can experiment on commercials and other projects while making a living.

“I felt it was important to explain this perspective to the class because saying no can sometimes be very difficult. But that’s also part of shaping your career.”

“One can get lost in all the technical details of the gear — and I’m guilty of it as well — but it’s the core principles that will save you when you’re pressed for time and have to rely on instinct.”

— Vance Burberry, ASC, ACS

Burberry, who was recently inducted into the ASC but has long taught elsewhere, observes, “Teaching is fundamental to the job of being a cinematographer, whether it be with your director, producer or crew.”

One of Burberry’s passions is underwater cinematography. “We couldn’t do an underwater class this time out,” he says with a smile, “so I wanted to focus on how I approach the basics of lighting, the foundation of everything we do. Often, one can get lost in all the technical details of the gear — and I’m guilty of it as well — but it’s the core principles that will save you when you’re pressed for time and have to rely on instinct. All cinematographers can relate to that. Time is not a luxury we often enjoy on set.”

Speaking to the tradition of cinematographers being both lifelong educators and students, Burberry recalls, “A few years ago, I was at Camerimage to receive a lifetime-achievement award for my work in music videos, and there was Stephen Burum [ASC], also getting a lifetime-achievement award, so I had a chance to talk to him a bit. More importantly, I had the opportunity to thank him, because about 30 years ago, he’d been my teacher in a way. I was a gaffer at Propaganda Films, and I had a question about color and secondary color in film, and he made the time to talk to me and was super helpful. I was so grateful to him and other iconic cinematographers I met as I was coming up, including Allen Daviau [ASC]. They were all happy to share, and I always remembered that.

“For me, teaching is about trying to help someone on their path to self-discovery to grow on their own,” he adds. “We’re just giving them some tools to help them on their way, as well as some encouragement.”

In a recent Master Class session that focused on shooting film, Gainer — curator of the ASC Museum Camera Collection and an expert in vintage production tools — combined his shooting experience with his love of history. “Hand cranking and operating a vintage motion-picture camera is a unique, tactile experience,” he says. “It’s completely different than the interaction we have today with digital cameras. And that can lend itself to creative possibilities.”

In a demonstration conducted at MBS Outpost, Gainer shot camera tests with model Nancy Cantine using a 1912 Pathé Professional fitted with a 35mm Goerz Hypar f/3.5 lens, and a 1921 Mitchell Standard (formerly owned by the great Charles Rosher, ASC) paired with a 50mm Gundlach Ultrastigmat f/1.9 lens. The film was Kodak 5222 Double-X, with processing and transfer work later done by FotoKem.

“What really left an impression on the class was the quality of the images that can be created with these early film cameras and lenses.”

— Steve Gainer, ASC, ASK

“What really left an impression on the class was the quality of the images that can be created with these early film cameras and lenses,” says Gainer. “Our perception of the silent era has been largely shaped by the prints that have survived, and many of those are in rough shape. And possibly, they didn’t even look that great back in the day because print stocks and exhibition were quite primitive. But looking at the images we created, scanned right off the camera negative, you can see how very capable these systems were in skilled hands. That concept might stick in someone’s mind, and maybe they’ll use it in a new creative way.”

Rodrigo Prieto, ASC, AMC recently employed Martin Scorsese’s own Bell & Howell 2709 hand-cranked unit for sequences in their Oscar-nominated feature Killers of the Flower Moon.

“The quality of Master Class is all about the people who teach it, and that’s a reflection of the ASC as well,” Lieberman concludes. “A founding principle of the Society in 1919 was to share information and help better everyone’s work. And today, that’s where the generosity of our members — freely sharing their time and experience — really makes the difference.”

Click here for more information about the ASC’s signature education program.