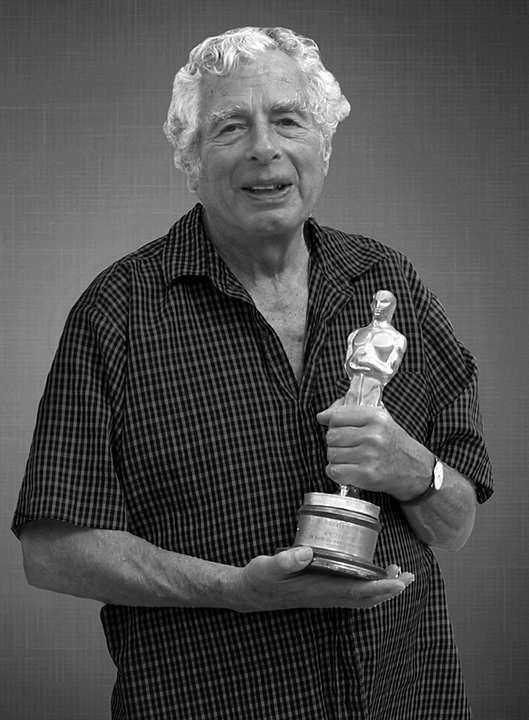

Remembering Walter Lassally, BSC

In honor of the Oscar-winning cinematographer’s passing on October 23, 2017, at the age of 90, we revisit his exemplary life and career.

Editor’s note: The following article was published by American Cinematographer in February of 2008. In honor of Lassally’s passing on October 23, at the age of 90, we revisit his exemplary life and career.

A Cinematic Passport

Influential cinematographer Walter Lassally, BSC earns the ASC International Award.

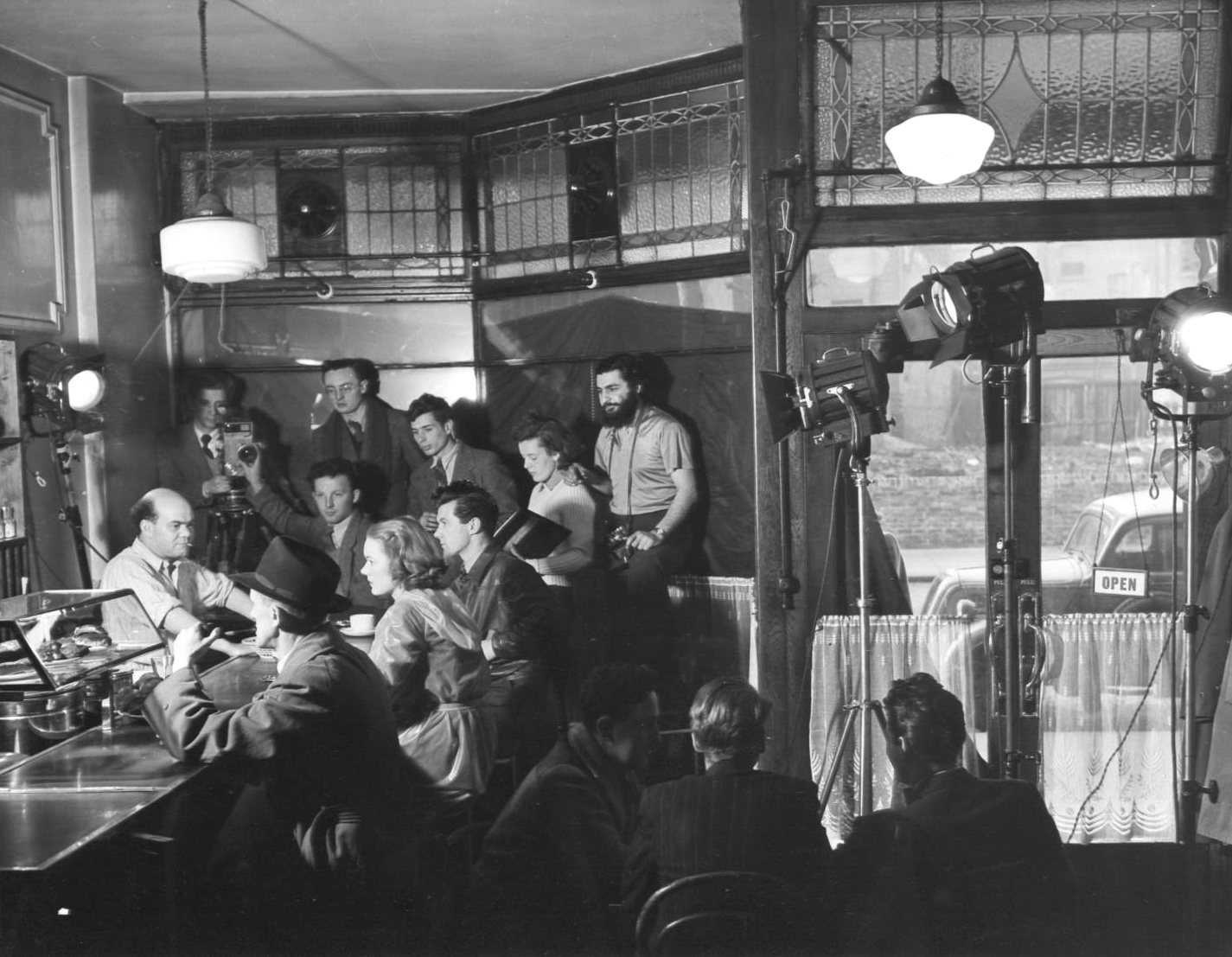

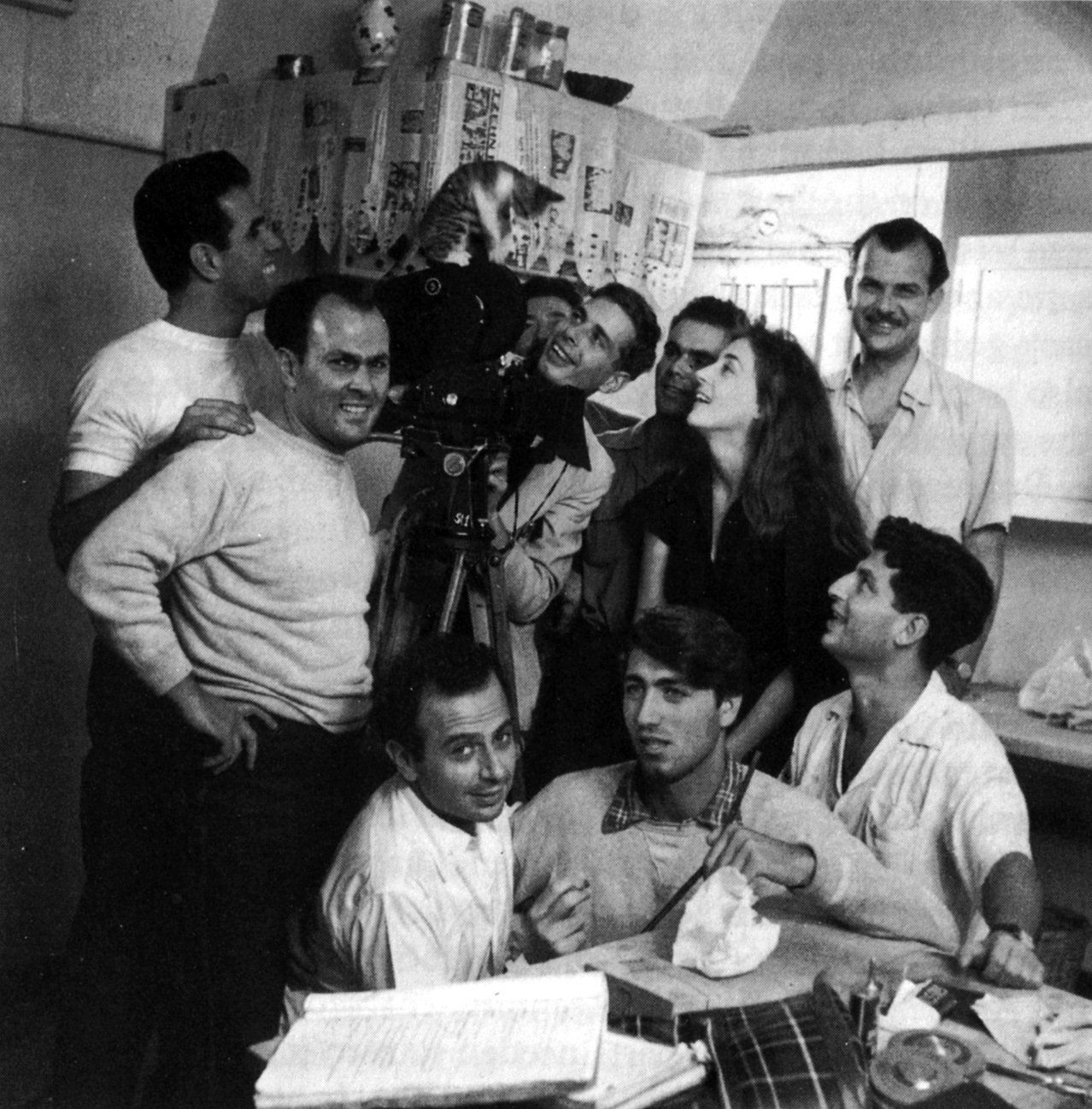

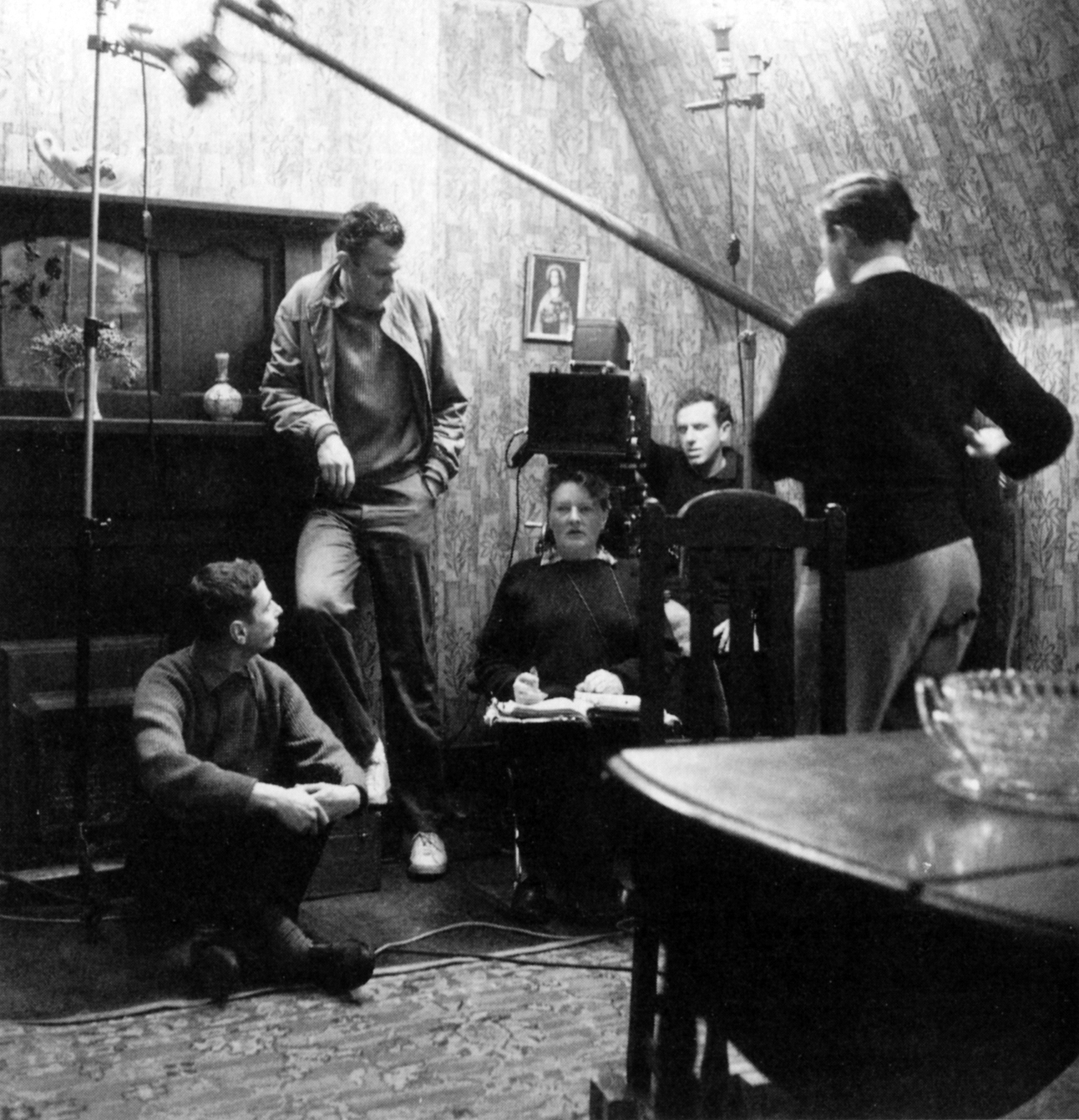

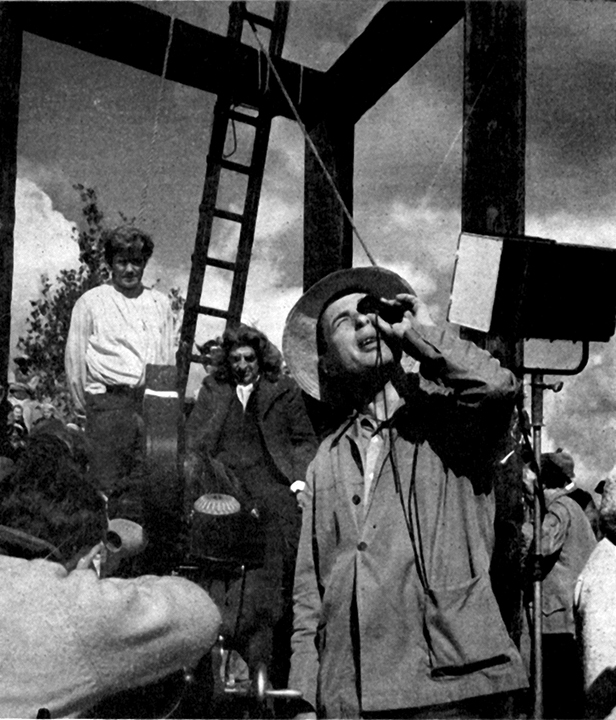

Photos courtesy of Walter Lassally

Director of photography Walter Lassally, BSC recently received the 2008 ASC International Award in recognition of his unconventional and influential career. Along with directors Lindsay Anderson, Karel Reisz and Tony Richardson, Lassally was a key player in the evolution of the Free Cinema and British New Wave movements. Tirelessly innovative, the cinematographer often made a virtue of necessity, especially early in his career, and brought a calm, can-do attitude to every set. He was an early adopter of HMI lighting, Arriflex cameras and high-speed film stocks, and a master at bending advances in technology to satisfy the requirements of the story at hand.

Lassally’s career spanned 50 years and took him to all corners of the globe. His feature credits include Michael Cacoyannis’ Zorba the Greek (1964), for which he won an Academy Award for black-and-white cinematography, and his documentary work includes Lindsay Anderson’s Academy Award-winning short film Thursday’s Children (1954). For Tony Richardson, he photographed the innovative movies A Taste of Honey (1961), The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner (1962) and Tom Jones (1963). For producer Ismail Merchant and director James Ivory, he shot the features Savages (1972), The Wild Party (1975), Autobiography of a Princess (1975), Heat and Dust (1983) and The Bostonians (1984), as well as Adventures of a Brown Man in Search of Civilization (1972) and Hullabaloo Over George and Bonnie’s Pictures (1978).

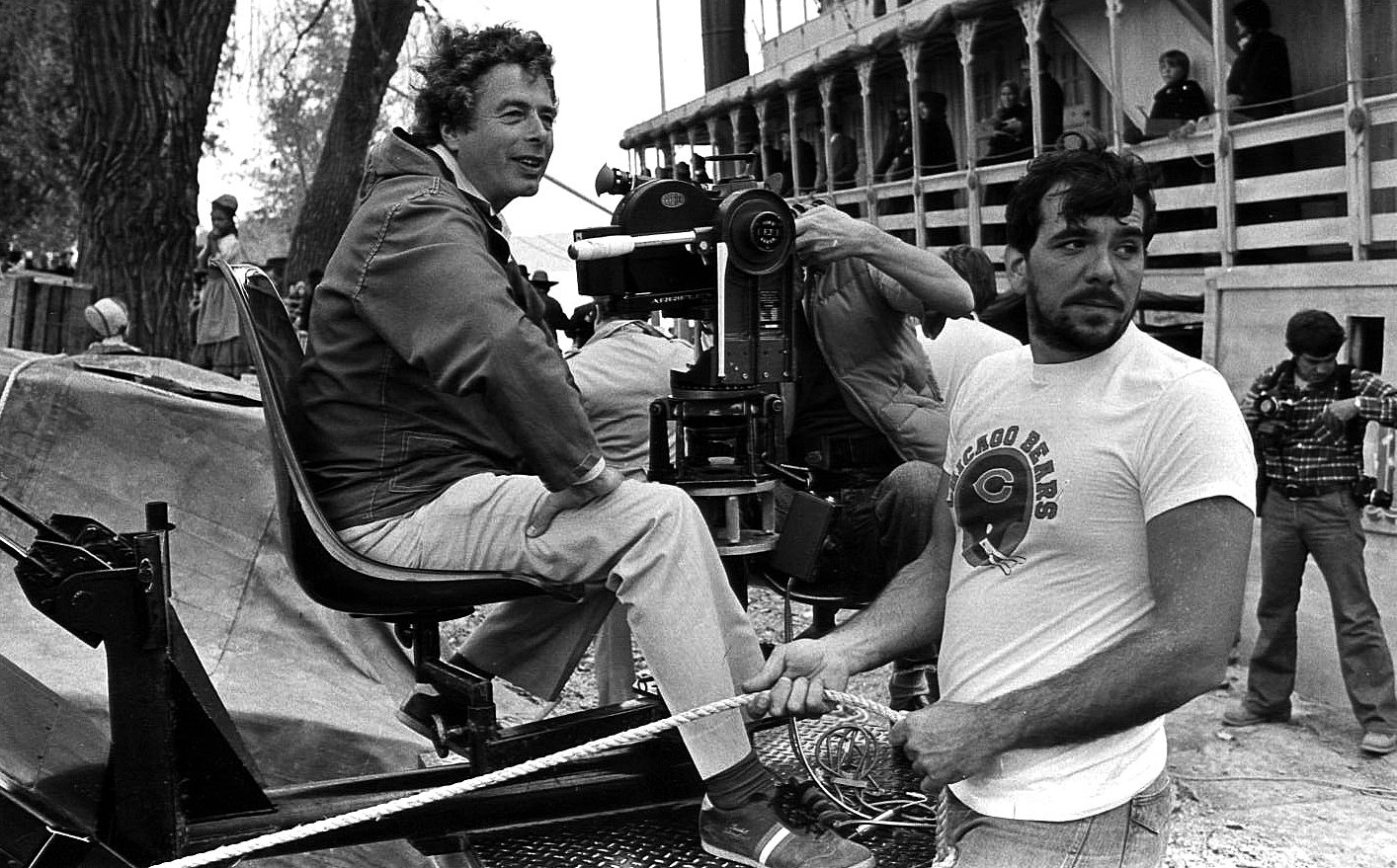

(lower right) provides fill light as Gerry Turpin

operates and John Fletcher operates the dolly.

Lassally was born in Berlin in 1926. He and his parents fled to England shortly before World War II began, eventually settling in Richmond-upon-Thames, Surrey. Lassally learned some of the technology behind filmmaking from his father, who made industrial films, but he says the roots of his obsession with cinema lay in the “nine pennies,” the inexpensive neighborhood theaters where he saw commercial movies. “I saw Warner Bros.’ thrillers, MGM musicals and other offerings of contemporary Hollywood,” he recalls. “That’s when my ambition to be a cameraman first took shape. By age 15, I knew exactly what I wanted to do with my life: I wanted to be a cameraman and shoot feature films. Rather arrogantly, I felt I, too, could create images and lighting such as I saw in those films. Immediately upon leaving school, I mounted a concerted campaign to get into the industry. In 1944 and 1945, I wrote to all the film studios to try and get in as a clapper boy.”

Desmond Davis assists.

In the meantime, Lassally took a job at a stills studio, where he often borrowed a Leica and film, taking advantage of the opportunity to shoot, process and print his own photos. “My first jobs in filmmaking were on documentaries, where the small crews meant that I helped in every aspect, which was valuable experience,” he recalls. “I worked on films such as A Demonstration of Lifeboat Launching by the 6x4 Scammel Tractor and Prefabricated House Components.”

Eventually, his letter-writing campaign succeeded, and he joined Riverside Studios as a clapper boy. His first job was on the feature Dancing With Crime, which featured an actor named Richard Attenborough in his first starring role. “In those days, one was very much on one’s own,” notes Lassally. “Learning cinematography was a matter of doing it because there were no film schools. You could watch and copy people, and I did have the opportunity to do that; I was able to work with people who were good craftsmen. For example, I was clapper boy on This Was a Woman for a very talented German cameraman, Gunther Krampf. He had an extremely meticulous method of working, which in those days wasn’t all that uncommon given that there were 26 or 28 weeks of production. Some of the lessons I learned are still useful today, and others have become old-fashioned.”

Riverside eventually went out of business, and Lassally went to work in a 16mm film library. During his free time, he joined film societies, where he befriended Derek York. He and York decided to make a short film, Smith, Our Friend, about squatters in London, a topic in the news at the time. “During the making of that film, I noticed that the primitive lighting dictated by the very cramped conditions helped to give the scenes more realism,” says Lassally. “That was an important discovery for me.”

Smith, Our Friend was well received at the annual screening of the Federation of Film Societies, and that led to another film, Saturday Night, which was made during 1949 and 1950. Although audiences never saw Saturday Night, a producer who watched some of the rushes offered Lassally his first job as a lighting cameraman. The project was a government trailer, the equivalent of a public-service commercial.

By the early 1950s, Lassally was shooting documentaries and short fictional films for Richardson, Anderson and Reisz, directors with whom he would eventually collaborate on features. In 1954, at the age of 27, he earned his first credit as a director of photography on Another Sky.

Most of his early feature work was abroad, outside the major studios, and often involved very small crews. Almost from the start, feature and documentary work were intermingled. “I valued the cross-fertilization of ideas and techniques that combination provided,” he says. “My own philosophy tended to keep me outside the mainstream of British and American feature productions, a course that I regretted occasionally but fleetingly. On balance, the creative opportunities seem to me to have always been greater on the fringes.”

The cross-fertilization between features and documentaries was crucial to the evolution of Free Cinema, an attempt by a small group of socially aware artists to counter mainstream films that they believed ignored the real world. The goal of the Free Cinema movement, which was formally introduced with a program of short films at the National Film Theatre in February 1956, was to produce short, low-budget documentaries about ordinary, working-class people. Tapping Italian Neorealism and the work of British filmmaker Humphrey Jennings (Listen to Britain) for artistic and ideological inspiration, the Free Cinema filmmakers took their cameras into the streets and often worked with relatively unknown actors and actresses; at the time, British films were predominantly adaptations of literary classics and were mainly stagebound.

Richardson (standing next to him) talk over a

shot on location for A Taste of Honey (1961).

Free Cinema’s manifesto, which was crafted by Anderson, read in part: “As filmmakers, we believe that no film can be too personal. The image speaks. Sound amplifies and comments. Size is irrelevant. Perfection is not an aim.”

Lassally’s cinematography contributed to Free Cinema’s Momma Don’t Allow (1955), Every Day Except Christmas (1957), We Are the Lambeth Boys (1958) and Refuge England (1959). “Studio films at that time were very conservative and never showed any working-class people at their jobs,” he notes. “So films like ours were very unusual. In fact, hundreds of people were turned away at the first screening [in 1956] because the program sold out.

“Free Cinema was later referred to as a movement, though it was never really that,” he continues. “Lindsay Anderson coined the term as an umbrella to cover that initial program, but the only thing the films had in common was that they were produced outside the industry by people who had little or no filmmaking experience.” (The February 1956 program comprised the shorts O Dreamland, directed by Anderson; Momma Don’t Allow, co-directed by Reisz and Richardson; and Together, directed by Lorenza Mazzetti.)

“Lindsay, Karel and Tony had ambitions to be feature-film directors but also wanted to show a side of life you didn’t normally see in the cinema, and they found common ground almost by accident,” continues Lassally. “But Free Cinema was a ripple compared to the French New Wave, which launched the careers of dozens of directors.”

Advances in filmmaking technology, including the introduction of the Éclair NPR camera and faster film stocks, were important aspects of Free Cinema, but Lassally notes that the filmmaker’s sensibility was more important. “In these days of ubiquitous television coverage of every conceivable subject, it’s hard to imagine how difficult it was to break the mold of what passed for realism during the ’50s,” he says. “The progress we made was largely due to a different mentality. The experience I gained shooting documentaries and short films came in very handy when I started shooting features; I knew how to insinuate actors into natural locations and how to add visual excitement to action sequences.

“The technical advances mostly came a little bit later,” he continues. “I shot Momma Don’t Allow with a spring-wound Bolex camera with a maximum running time of 22 seconds. In retrospect, the considerable technical limitations were a stimulant rather than a hindrance. They didn’t stop us from doing good work. There are a lot of things you can do with very little money and limited technical means — it’s the eye behind the camera that is important. Progress continues on the technical side, but it’s creative ideas that are always in short supply. I’ve always found that more money equals more hindrance, because the money seems to always be connected with people who look over your shoulder and have to be pacified.”

During the next decade, Lassally made six films with Cacoyannis that were shot mostly at practical locations in Greece. They first teamed in 1955 with A Girl in Black, and their final collaboration was Zorba the Greek. Lassally says the lighting of A Girl in Black was fairly primitive, consisting mostly of older French 1K and 2K spotlights. At a small studio in Athens, he unearthed an old discarded “cone light,” an early forerunner of today’s soft lights that reflected light from the white housing onto the subject. He used it to provide soft fill for interiors.

In 1962, Lassally and Cacoyannis made Electra, starring Irene Papas. The film was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Foreign Film and won multiple honors at Cannes. Lassally considers it one of his best pictures. “Michael and I had very much the same viewpoint and eye,” he observes. “He could leave the final execution of the images completely to me and still get exactly what he wanted. His scripts were written in shots rather than scenes, which was unusual, but I felt it to be a perfectly reasonable way of working. Scenes were described in such detail that you could imagine the pictures immediately.”

During the mid-1960s, Lassally collaborated with Free Cinema colleague Richardson on A Taste of Honey, The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner and Tom Jones. A Taste of Honey was the first British feature made for a major distributor to be shot entirely on location. It was also one of the first films to use three different types of film stock, including one previously considered suitable only for newsreels and documentaries. “For A Taste of Honey, Tony wanted an all-location film,” recalls the cinematographer. “So many films are made on location today that it is hard to remember that the idea was once very difficult to sell to the financiers — they were afraid a lack of sunlight would delay the shooting interminably! It was impossible to convince them that for greater realism, it was actually desirable to shoot exteriors without the sun. As for my intention to use three film stocks, there was considerable opposition from the laboratory, but it proved entirely successful. I did the same thing a few years later on Zorba.”

Winning an Oscar for Zorba led to many offers from Hollywood. “I got my offers from major American directors, including Otto Preminger and Stanley Donen, but I turned them down because I didn’t like the scripts,” says Lassally. “It can be dangerous to aspire to bigger films. I found the bigger they were, the less likely they were to be better. To this day, I’m more interested in the work of Jim Jarmusch and John Sayles. Most mainstream films are made for people aged 7 to 17. I have nothing against making pictures for teenagers, but why only for teenagers? It’s regrettable, because there is a huge worldwide audience out there that has stopped going to the cinema.”

Lassally continued to take on documentary work, including The Greeks (1967) and the 1968 Olympics in Mexico City, as well as features such as Joanna (1968). In the early 1970s, he began a creative association with Merchant-Ivory that lasted for more than a decade, and the cinematographer’s extensive experience with making do on location with limited technical means came in handy on location in India, where a number of the duo’s films were set. Lassally earned BAFTA and BSC award nominations for his work on Merchant-Ivory’s Heat and Dust and The Bostonians. “Heat and Dust seemed to start off a whole new wave of British productions made in India, including such epics as Gandhi and A Passage to India,” he says. “I considered Heat and Dust my best film since Electra.”

The 1970s also brought Lassally jobs in the United States. Cinematographer Tom Houghton, ASC, then a gaffer, worked with Lassally on several U.S. productions, including the telefilm Too Far to Go. “Walter knows his stuff backwards and forwards,” says Houghton. “He knew how to keep things simple based on the budget and the schedule. We were able to use HMIs, which were relatively new — the biggest was a 4K. We also used umbrellas for bounce to create soft lighting setups. He was also great with hard light. He took a great deal of care in the placement of lights, and it was an amazing experience to watch him. The more I worked with him, the more I understood what he was going for. He knew how to create subtleties and nuances in the midst of simplicity, and he brought that sensibility from the smaller projects to the bigger films. We developed a trust and friendship that had an important impact on me in that early phase of my career.

“Walter’s early films, like Every Day Except Christmas [1957] and Beat Girl [1959] were radical, and by watching them I learned the importance of using a location for its atmosphere,” Houghton continues. “Walter never overwhelmed a location with lights just because he had them. As a result, you get the beautiful light and textures of places like India and Greece. The lesson is the simplicity and the lack of indulgence.”

Robert Primes, ASC worked with Lassally on the telefilm Gauguin the Savage (1980). “I learned a lot about cinematography from Walter,” he says, “but more than anything, he became a role model for how kind and calm someone could be. He would never boast or brag. He was often self-deprecating, and I realized the effect that had on others. It was disarming and put people at ease. At the same time, it spoke of a great, easy confidence. I decided I wanted to deport myself on set in that same calm, relaxed way. Ever since then, I have tried to emulate Walter in that regard.”

Lassally continued to shoot film and television projects through the 1990s, including The Ballad of the Sad Café (1991), The Man Upstairs (1992) and Nature Perfected: The Story of the Garden (1995). He also devoted a lot of time to teaching at the American Film Institute, the Maine Photographic Workshops, England’s National Film and Television School, and elsewhere. His memoir, Itinerant Cameraman, was published in 1987. He lives in Crete and still gives occasional seminars.

Lassally recalls his first visit to the ASC Clubhouse, which occurred in 1974: “It was an extraordinary experience, as it enabled me to put faces to many of the legendary names whose work enthralled me during the ’40s and ’50s. Their Hollywood films were an important part of my education and what I sought to emulate. I knew their names, but I never dreamed I’d meet them. To my surprise, there they all were, wandering around with nametags on their jackets. They gave me a very warm welcome.”

Of the ASC honor he received last month, he says, “I was very grateful to receive the award from the ASC because it’s an honor given to you by people of your own kind. However, I always feel somewhat embarrassed when I’m singled out for what I regard as over-lavish praise. In my opinion, the photography of a film has failed if it draws too much attention to itself, and in my work, the real author of the effects [viewers] so admired was often God.”