Rock Stars: Bohemian Rhapsody

Newton Thomas Sigel, ASC brought an epic sense of showmanship to this compelling and uplifting biopic.

Newton Thomas Sigel, ASC brought an epic sense of showmanship to this compelling and uplifting biopic.

Unit photography by Alex Bailey, courtesy of 20th Century Fox.

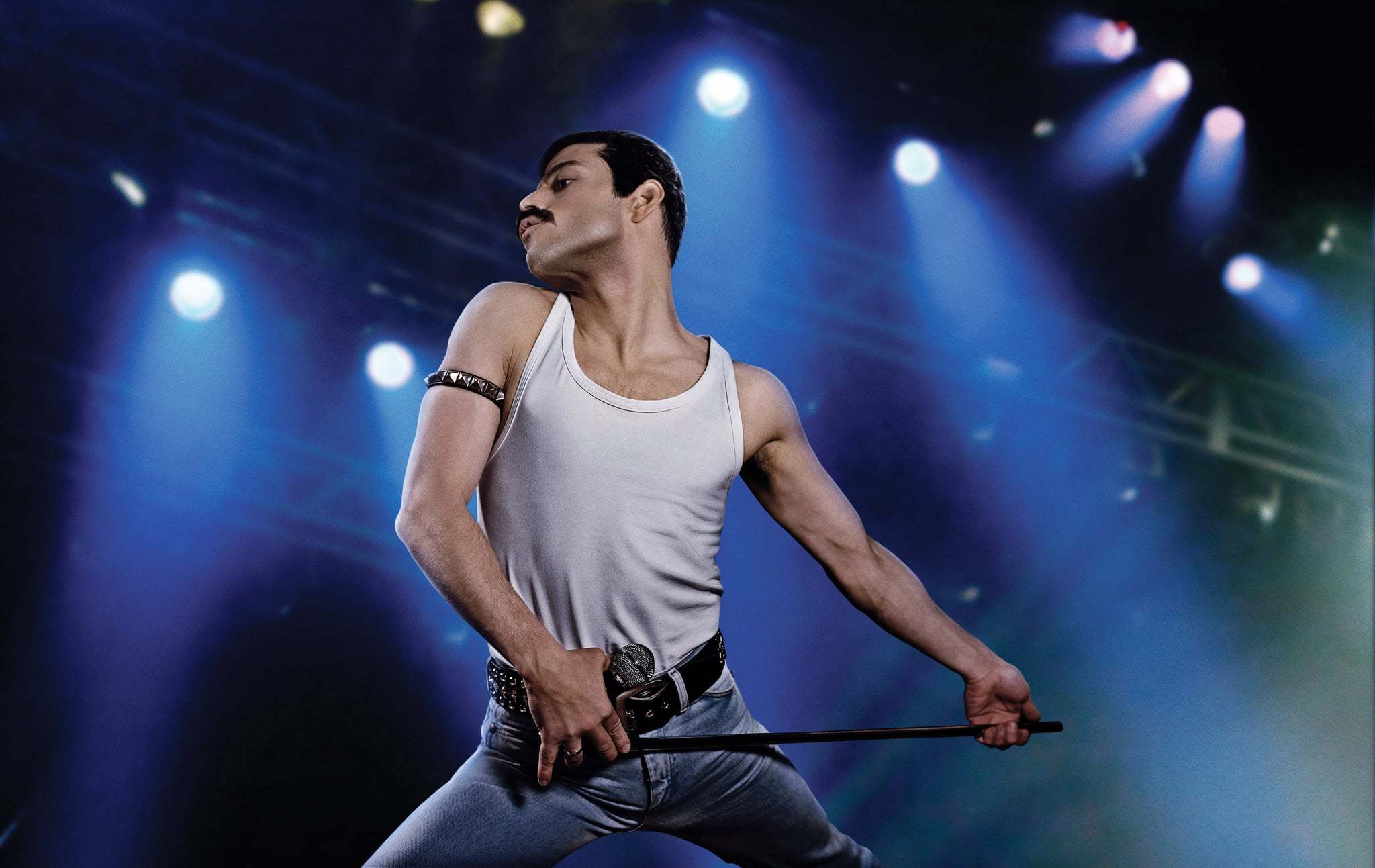

The worldwide hit Bohemian Rhapsody tells the story of Queen, one of the most beloved rock bands of the 1970s and ’80s, and its dynamic front man, Freddie Mercury, played by Rami Malek. The film avoids standard rock biopic tropes, eschewing the usual rise and fall trajectory of the genre in favor of an ebullient, celebratory energy. ASC member Newton Thomas Sigel’s cinematography visually charts the evolution of the iconic group with vibrant color, dynamic camera movement and lighting faithful to the many archival photos and films to which Sigel had access as research.

American Cinematographer: When you were initially hired to shoot Bohemian Rhapsody, what were your first steps toward formulating a visual approach?

Newton Thomas Sigel, ASC: I started from a jumping-off point of looking at all of the archival material of Queen — watching a lot of the live performances and the documentaries. Reading all the books I could. I then started to formulate an idea of the way they evolved from 1970 to 1985, which is when our story takes place. I was interested in the relationship between their evolution and what was happening culturally, because they came in right at the tail of the counterculture movement and the hippie movement. It wasn’t long into their career that glam rock took hold, and eventually things like disco and heavy metal. The time period of our movie traveled through this cultural shift, as well as their growth as artists, so I looked for ways to express that.

In their early days, there’s still this romantic glow connected to the ideas of the counterculture — an idealistic notion about making music as opposed to being the star or being an image. I shot those scenes with the ARRI Alexa SXT, and I used the old Cooke Speed Panchro lenses. I created a particular look for that period that was a little grainier, that had a very warm glow in the highlights, with the cooler foundation, and shot it almost all handheld.

Then, there was a transition that was made when Queen got introduced to the world at large — they went on Top of the Pops and toured the United States. Eventually, we landed in a large format using the Alexa 65 with some of the DNAs and some purpose-built lenses from ARRI. We also moved to a different LUT that became increasingly cleaner, more desaturated and more representing where they were going as a band. And what was happening in the culture as well. By this point the movie is much less handheld, much more dolly, Steadicam and crane, and less grainy.

Interspersed along the way you have other formats for historical reasons. I shot the television footage with Betacams that were considered the forefront in technology at the time. We shot the “I Want To Break Free” music video on film — we actually found the camera used to shoot the original video. I didn’t want it to be like a switch that got flipped and all of a sudden the format of the movie changed, but I was looking for a way for a more checkerboarded transitioning into this other kind of palette and grammar.

“As a guy who tends to like darker movies, I initially thought, ‘Oh, I want to make it darker, starker, more unpleasant movie.’ But, the more I thought about it and developed it, the more I actually really enjoyed doing something that wasn’t about destroying your faith in humanity.”

Since you mentioned the palette, can you describe your use of color in the movie? I feel like it evolves during the various periods just like the camera movement and lighting.

That’s true. I worked very closely with the production designer, Aaron Haye, who is a really talented guy. We were on our own a little bit in prep because [director] Bryan [Singer] was dealing with personal issues, so Aaron and myself and our AD, Jack Ravenscroft, scouted all of the locations. I would take a camera or an iPhone and use those two guys as actors, blocking shots or scenes or angles to get a sense of what locations worked. That was a great opportunity to discuss color with Aaron, who made great use of the archive of material that existed to reflect the palettes of the different periods. For me — and I think this is something that a lot of cinematographers deal with — you also have to remember that a lot of the archival material has a bias in its palette based on the technology that recorded it. So when you’re looking at something that was shot in the ’60s with Kodachrome, you have a very different sense of color and what the look of the time was than you do when you’re looking at an Ektachrome slide from the ’80s. So I kind of used that a little bit as my freedom to be poetic and create color palettes that to me reflected more the psychology of the period than the specific design colors of the era.

In terms of that psychology, I feel like you do a lot of interesting things to express internal points of view. For example, there’s a scene at a press conference where everything is falling apart, and you visually fragment the image to allow the audience to share Freddie’s perspective. What was your approach to that scene?

The script infers that he’s under the influence, whether it was alcohol or drugs. He's really going down a self-destructive, or at least a hedonistic, path. Also, the underlying history that’s important to know at that moment in the press conference is that Queen, at that point in their career, with all their popularity, had never gotten real critical acclaim. They were becoming hugely popular, but the critics were often antagonistic. So they had this love/hate — more hate probably than love — relationship with the press. You put those two things together, and the intent of the scene was to show that Freddie's path was diverging from the band at that point. Personally, as he became clearer about his sexual identity, he was going down a different lifestyle than the rest of the band. Not that the other guys were all a bunch of angels, but he was clearly going in a different direction. It’s quite a remarkable study in the fact that the four of them still truly contributed to a sum that was greater than the parts.

In the press conference, the idea was to show this rabbit hole that Freddie was starting to go down. The idea was that it begins as a relatively normal press conference, and the photography’s somewhat normal. But, there’s a lot of antagonism in terms of the questions that are coming from the press. Because of that, it just preys on Freddie’s drunken or drug-addled state of mind. He can’t cope with it, and he becomes increasingly disoriented until he flips out. So, I looked at a number of different lens modifications, and although it wasn't exclusive, the one that really spoke the best to me was an old Zeiss. We took one of the internal elements and flipped it, so that’s what they call a reverse optics. It kept the center of the frame somewhat normal, albeit a little distorted. Then the distortion increases as it goes out towards the edges of the frame. So it’s not really a swing/shift lens. It’s not a Mesmerizer. But it’s a very particular type of distortion that, to me, really spoke to where Freddie was at. It does particularly interesting things when you move the camera, which we don’t do at the beginning of that, but then toward the end you start to see it pan. So you’re actually panning through from clarity into more distortion. It creates a really disorienting effect, which is what was going on in Freddie’s mind. That combined with a little bit of a more traditional swing shift in some of the stuff on Freddie, and another lens that we had sort of de-tuned the edges for Freddie’s close-ups. I thought that our editor, John Ottman, did an excellent job of building that disorientation, so that you feel it grow as the conference goes on. Yeah, it was one of the scenes that I was most happy with.

That leads me to a more general question I had about lenses. The movie is shot in a ’Scope aspect ratio, but you used spherical lenses. I'm curious — what kind of factors go into deciding whether to go spherical or anamorphic when you're shooting in that aspect ratio?

Well, there are two different questions there. One is, if you’re shooting on a Super 35-size sensor or a negative, if you’re shooting film, you have the question of Super 35 versus anamorphic. That’s one discussion. That discussion in the old days of photochemical used to be about liking the advantage of using the entire negative with an anamorphic lens. And loving the blue flares, which people were obsessed with for many years. If you like the distortion that you get toward the edges of a lot of anamorphic lenses, it has a very particular feel. Many cinematographers live by it and swear by it and have really taken it to a fabulous place. And the fact that you’re using longer focal lengths, by definition your wide lens is like a 50mm or a 40mm, as opposed to a 17mm or a 21mm.

So, you have that valid discussion in the photochemical days, you have the discussion with grain versus lack of grain, sharpness versus [soft], because of what you had to do to get Super 35 to be an anamorphic release print. Then came digital intermediates and digital finishing of films. The grain issue and the issues of optical printing went away, and it really became more strictly about the lens choice. The question of which of these lenses do I like better, which do I think is more appropriate.

In the old days, there was much less range when you were just shooting [Panavision] E Series or C Series. There was a much smaller range of lenses that you had available than you do today. Now, with the introduction of large format, like with the Alexa 65, or as RED and Panavision are putting out their [DXL] 8K cameras with big sensors and everything, you need to have lenses that cover the size of the sensor. So the anamorphic/spherical question has gone on to also be about how much do I want to use lenses that I have to put something on the back of — some kind of expander — to cover the whole sensor? What does that do to the optics of the lens? How much do I want to achieve certain things, like longer focal lengths, just by using a larger sensor or a larger resolution with more, dare I say, medium-format-style lenses?

For Rhapsody, I tested some of the anamorphic lenses. I’ve done my fair share of anamorphic movies. But, for whatever reason, the DNA lenses and some of the ones they were starting to make for me were really speaking to me. They were giving me the longer focal lengths that I did want to use and that I did like for the second half of the movie. It was really interesting too, because unfortunately we couldn't shoot in continuity. You’d be there one day shooting where you’re instinctively going to your 45mm or 55mm lenses. Then the next day you’d go, “Yeah, let’s get the 25.” So that was an interesting, almost daily, transition. I would’ve loved to have shot the movie in continuity, but we went out of the gate with Live Aid.

To answer your question, I’m pretty agnostic. I actually love mixing it up. I did a music video for Arcade Fire just a little while ago where I got to use the Hawk Vintage 74s — they were scope lenses and they were fantastic. I loved them. They were really great. It didn’t make it in the movie, but we did do a little scene about Freddie’s childhood in Zanzibar, which I shot in 16mm with the 1.3 anamorphic, which is amazing. It’d be great if they release it as a DVD extra or something. One can only dream.

I want to touch on something you just mentioned. You said you were out of the gate with Live Aid, which seems to me a quite challenging thing to start the movie with.

It was insane. We did the old pre-shoot day — where they steal a day from prep — and make you shoot something ahead of time. On that day I designed this scenario that comes from Central London over Wembley. It comes down along the crowd, goes all the way up to the stage, wraps all the way around Freddie Mercury in the close-up and then the concert starts. They decided that that's what we should shoot on our first day. I was like, “Oh, my God.” Because the guys playing the band — this was their first gig, so to speak. The one saving grace for the band was that they intended to follow the original choreography very specifically, although we wanted to find a different way of shooting it. As Bryan said, there was no point just reproducing the angles that the BBC did for the broadcast, because you can go on YouTube and watch that.

I really needed to find a way to shoot it that was telling a very different story than what you saw on TV. From the minute I read the script and started researching the story, in a funny way I always felt that Live Aid was going be the hardest thing to shoot. It's the climax of your movie. It's the opening tease and the ultimate climax. It has two big obstacles. One is that the concert was done in the middle of the day in an outdoor stadium. At least they came on late in the day, which was a saving grace. The second obstacle is that the stage and the staging was purposely very, very bland. Bob Geldof and the promoters went out of their way to spend as little money on the staging of the concert as possible, because they were trying to raise money for Africa.

So we had a bland backdrop in the middle of the day for our climactic scene, after shooting things like Madison Square Garden and the “I Want To Break Free” video and all these other great visual feasts. Then, I had the complicating factor of reproducing the stage very faithfully. [Production designer] Aaron Haye did an incredible job of research and reproduced the stage out on an old airfield in Babington. But, of course, there’s no Wembley Stadium because it has long since been torn down. So anything that looked out toward the audience — even on an angle like a profile — there was no stadium out there. We had to do one song each day. I would've liked to have shot the first song for the first hour or two of each day and the second song for the next hour so there would be that continuity of light in the day. But I couldn’t. I had to shoot a song each day and control the sun, which started the day coming into the stage, and ended the day behind the stage, every day. I figured, “Well, we’re going to put a green screen out there, so I’ll do the old container box thing and cover it in greenscreen. Then I can use that to put a silk over the top, I can keep great continuity and I can give greater or lesser presence to the little bit of stage lighting that there was.” That was undercut when the effects guy says, “We’ll just rotoscope everything, except maybe we’ll need a little greenscreen here and there.” Then undercut further when they said, “Oh, we can’t afford to do that.” So, now I had a stage that was exposed to the elements, and I had to control the continuity of the sun. And the relationship between performers and background and the backdrop, every day, all day long, for over a week.

That was my first scene out of the box, with a crew I’d never worked with before. Then, of course, as we started shooting, the “We don’t really need greenscreen,” wasn’t always the case. It was like, “Oh, don’t we need a greenscreen there and a greenscreen there?” So it got more complicated and it was a challenge. One of the things I’ve been grateful for is that in the responses to the film, the scene that people just universally go nuts over is Live Aid, which is really heartening considering I thought that it had the potential to be a let down. It’s a real testament to Rami’s performance as well — that he carries it so well. I also think that the emotionality of him having the diagnosis before the concert — and his coming to terms with his parents and his sexuality — really elevated that scene and is the reason that people have responded to it so universally. So, I guess it says to the cinematographer: Maybe all the smoke and backlight in the world still won’t trump a really great scene.

How did you approach some of the other concert scenes in the movie?

Emulating Queen’s concerts and respecting the truth of their staging was really important to me. I think it’s also important story-wise, in that when you build the staging of their concerts from the beginning of our movie to the end — and this is why I was scared of Live Aid — you are really telling a story of the band. You’re telling a story of their success and their popularity, but also how they’re presenting themselves to the public and to their fans. The restriction I gave myself was that I was going to try to be true to what they did on stage at any given point in their career and to what the technology of the time was. So, I pretty much had PAR cans and focal spots and follow spots as my toolkit until much later in their career when the introduction of the Vari-Lite came around in the late ’70s or early ’80s.

It was a lot of fun. In the early days, there was some great stuff they did — like the drum riser with the aircraft landing lights, a three-stage, sort of a wedding cake, drum riser. I fashioned a crown out of a period equivalent of MR16s — like small incandescent lights that made a little crown. It was like some of the stuff they did in the early 1970s or ’73, ’74 — around the time of the Rainbow Room and all that. Then by the time we got to Madison Square Garden, I got to do these massive banks of hundreds and hundreds of PAR cans with programmed colored changes. It would’ve been great to use LED lights — it’s just so much easier and you can do so much more. But it was also great fun in being able to build and build and build the scale at the concerts. It was a challenge scheduling, because I think there was a two- or three-day period where I had to do four concerts. From what became Edinburgh to “Now I’m Here” to “We Will Rock You,” and we couldn’t afford to build and light multiple stages. So we had this one stage and one lighting setup that I could modulate and adapt to each one of the concerts and make look completely different. I worked with my gaffer, Lee Walters, and Tony Simpson, a concert lighting designer, to create a modular system with different racks of PAR cans and different tresses with different types of lights that could be moved up and down like a Lego set, where you could reconfigure the patterns.

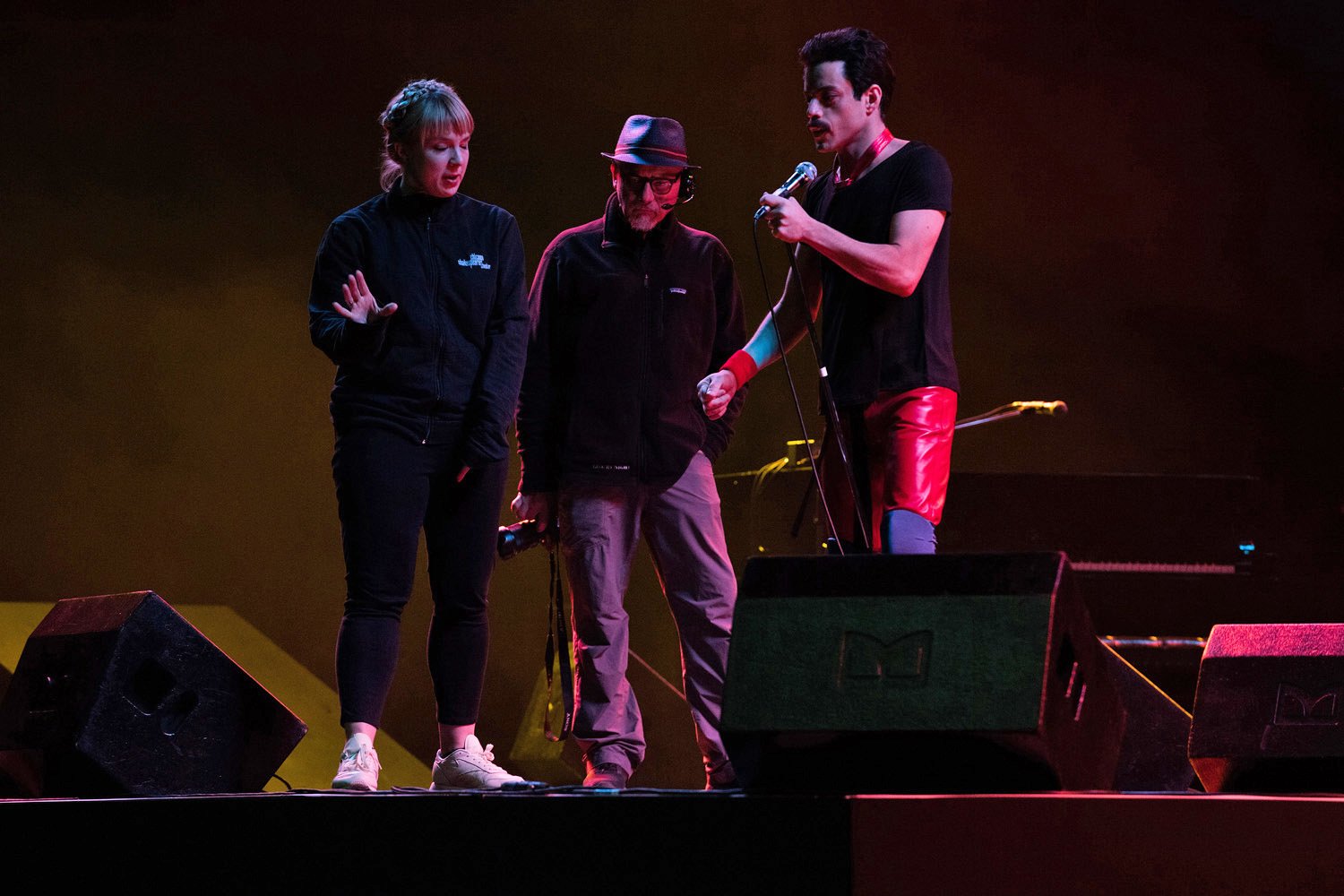

To add to the challenges, late in the shoot, Bryan Singer, who you have worked with on many films, was replaced by Dexter Fletcher. What was that transition like?

It was initially very traumatic for me in the sense that I really believed in the movie so much. I hate to sound like a cliché, but this really was a work of love. I mean, [producer] Graham King had been trying to make this movie for 10 years. I had the best of times with Rami and the band. We loved making this movie. Everybody wanted to make a really great movie. When Dexter came on, there was a moment of trepidation, because before he saw a cut he said, “I want my cinematographer,” because he’d only worked with one. He’d only directed a couple of movies [Wild Bill, Sunshine on Leith, Eddie the Eagle and the upcoming Rocketman], and he’d done them all with George Richmond, who’s a wonderful guy. I remember being told this and being heartbroken and calling George and telling him what I had planned for the rest of the shooting. While I was explaining it to him, I said, “Oh, geez, George, can I finish this call in a few minutes? I have to take my kids to school.” I got in the car, and I took my kids to school. I started to get into the Zen place of, well, George will finish the film, and that’ll be fine. And on my way home from the kids’ school, I got a phone call from Graham saying that he and Rami had talked to the studio and that there was no way that I couldn’t finish the film. That I had to come back, if I would. Dexter had gone and seen the cut, and after seeing the cut he said, “This is fabulous. What you guys are doing is fabulous, and I’ve got to respect that.” Of course, I was elated that I could go back and finish the film. I just had to meet Dexter and find out what he’s all about. He’s a very warm guy, and because he embraced the movie and what we had done so far, that actually made it fairly smooth and somewhat painless. There were times when I think Dexter wanted to bring a little more of his personality into the film, but he and Graham realized that wasn’t the kind of movie it was. I think his great respect for what we had accomplished up to that point was one of the reasons the film does have a cohesive tone.

Yeah, I was surprised by how smooth and cohesive it felt knowing the production history. And how fun.

Yeah, it’s funny, because, as a guy who tends to like darker movies, I initially thought, “Oh, I want to make it darker, starker, more unpleasant movie.” But, the more I thought about it and developed it, the more I actually really enjoyed doing something that wasn’t about destroying your faith in humanity. I think that a certain degree of the lack of critical love had to do with the fact that we had a director who went through a very difficult personal experience. When a director leaves a project and another takes over, it’s very, very hard for those who really do believe in auteurism of cinema or the purity of cinema to embrace the movie. It’s hard even for me! As a cinematographer, signing onto the next job, I look very, very closely to see if I’m working with somebody that has a vision. I think most cinematographers — if not all — will tell you that they’re looking for that director that has a strong creative vision. Someone you’re trying to stay up with, to catch up with, rather than the other way around. My most rewarding experiences have often been with directors that are considered difficult on difficult productions. Yet, they are the ones that have a strong voice, whether it’s Terry Gilliam or Nic Refn or David O. Russell. And very often they’re difficult for a reason, because they have a very strong point of view. So when you have a movie where the director doesn’t complete the movie, I think it was hard for the critics to embrace it critically. But you could tell that even in some of the reviews that weren’t raves, there was still a warm feeling for the movie at the end of the day, because the concerts are amazing and Rami was amazing. It’s hard to have all that greatness in a movie, so I feel pretty darn good about it