Russell Boyd, ASC, ACS: Vision Accomplished

The Australian cinematographer receives the Society’s International Award for a masterful, continent-hopping career.

Images courtesy of Russell Boyd, ASC, ACS and the ASC Archives.

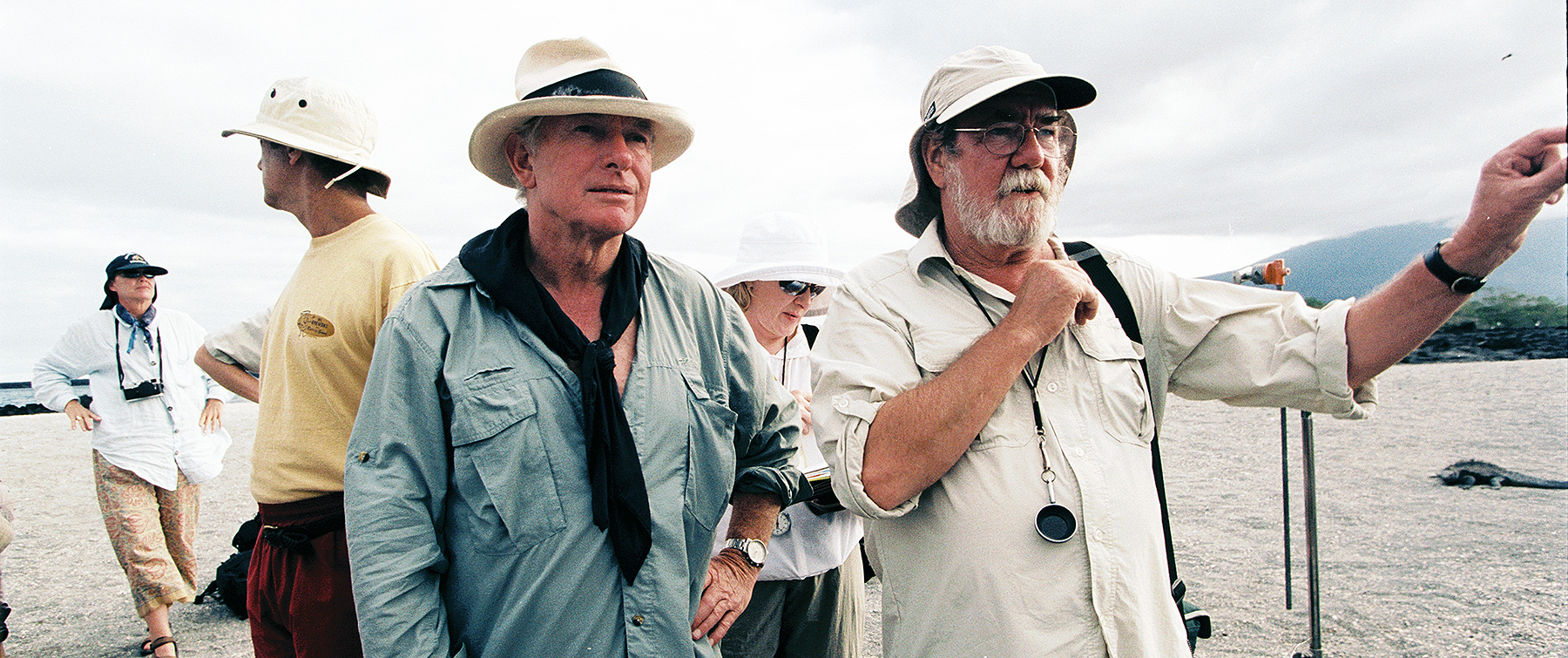

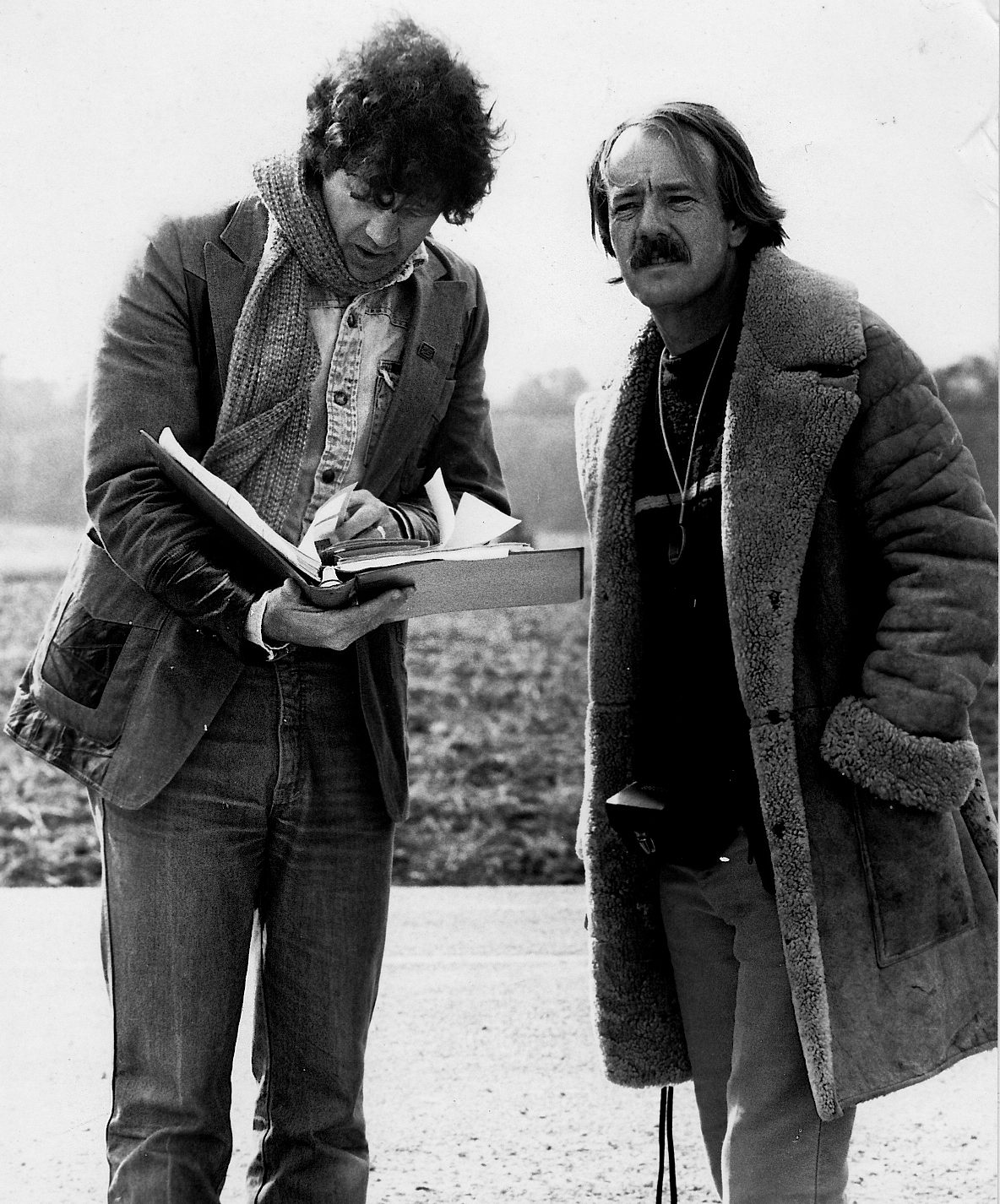

Picnic at Hanging Rock is widely considered to be the film that put Australian cinema on the world map. Shot by Russell Boyd, ASC, ACS, it was one of the movies that ushered in a new era in the country’s film industry — an era referred to alternately as the Australian New Wave, the Australian Film Renaissance and the Australian Film Revival. Boyd, the recipient of this year’s ASC International Award, was a seminal figure in that movement, as was Picnic’s director, Peter Weir. (Both pictured above.)

Picnic marked Weir’s second film and Boyd’s third — and the first of six pictures the two men would make together. “I was very fortunate,” the veteran cinematographer tells AC, speaking by phone from his home in Sydney. “The industry was just starting to fire up again, after an earlier period of activity in the 1920s. The government saw movies as a way of introducing Australia to the wider world. Geographically, we were far from anywhere. Nobody in the rest of the world knew much about us; if anything, they considered us country bumpkins. It was really a cultural decision on the part of the government, which proceeded to set up film commissions and started financing projects. It was very forward-looking of them.”

Boyd’s own interest in filmmaking sprang from an early passion for photography. Born in Melbourne, he was 5 when his family moved to a small farm just outside the town of Geelong, which served as the rural center of the wool trade. Boyd’s father was a wool classer. “He traveled around Victoria giving a grade to the fleece,” explains Boyd, who sometimes accompanied his father on his rounds. The elder Boyd did not encourage his youngest child to follow in his footsteps, however; he recognized that the industry was losing its vaulted position in the Australian economy to mining.

When Russell Boyd was 14, his older brother and sister moved back to Melbourne — his brother to pursue university studies and his sister to train to be a nurse. “From the age of 14 on, I was on my own or with me mum,” he recalls. “I had developed a keen interest in photography and bought my first camera, a single-lens-reflex Japanese Kowa. I didn’t have any arts education but, because I grew up in the outdoors, I think I became conscious of how the country looked. And when you go into the Outback, you do feel a spirit there in the wide-open spaces.”

His initial thought was to become a stills photographer, maybe to work for a newspaper. “Gee, I’m glad I didn’t do that,” he says, laughing. “When I was 15 or 16, my mother took a train into Melbourne and went around to a number of newspapers trying to get an internship for me. She was great. She knew that one day I’d be leaving home. The last place she went was a company called Cinesound Newsreel. They were looking for somebody to help paint sets for TV commercials, project film and be a general assistant.”

A few days shy of his 17th birthday, Boyd left Geelong and entered the work force. Having been isolated on the farm for most of his youth, Boyd hadn’t seen many movies; once in Melbourne, he spent weekends at the cinema and realized what a powerful medium film was — one that could have a huge influence on people. He started thinking about shooting drama as a profession.

During his three years at Cinesound, Boyd taught himself to shoot. He bought himself a 16mm Bolex, and on weekends he started freelancing for Seven Network — aka Channel Seven — in Melbourne. Soon he was shooting news there full time; covering a plane crash that killed two young men, however, turned him off to “shooting life in the raw,” he says. He moved to Sydney and took a job working on documentaries and commercials at Supreme Studios. There he met future ASC and ACS member Peter James, who became a lifelong friend.

“Russ was 19 when he first came here — I was 15 or 16 — and he already had been shooting and getting good reviews for his work,” recalls James, speaking from his home in Australia. “He was a cameraman in his own right! It was very impressive. He was unpretentious, very down-to-earth — and he hasn’t changed a whit in all these years. He’s still the same sweet guy, extremely modest and humble. When you look at his films, you can’t imagine them being photographed any other way; the cinematography is so sympathetic to the script and story, the actors and subject. I’d come out of one of his films and say, ‘Oh, damn! He’s done it again.’”

Boyd spent five years at Supreme before moving to Robert Bruning’s Gemini Productions to shoot 30- and 60-minute dramas. He left when a friend, Michael Thornhill, asked him to shoot his directorial feature debut, Between Wars. Shot in 1974, the film earned Boyd the ACS Cinematographer of the Year award. He received the honor again in 1982 for Weir’s feature Gallipoli, and was inducted into the ACS Hall of Fame in 1998.

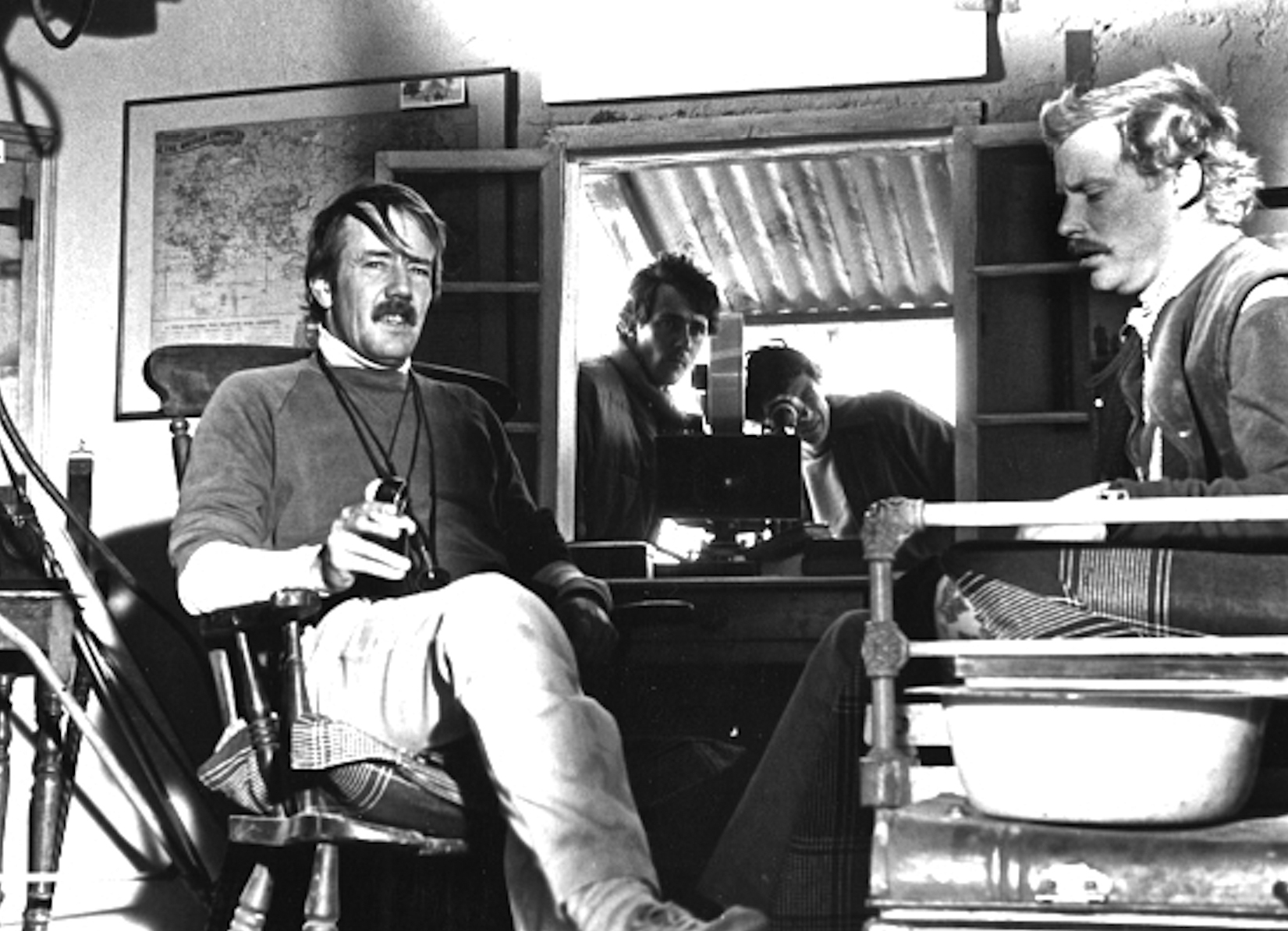

It was Boyd’s work on Between Wars, particularly the day-exterior scenes, that caught the attention of Weir, who was looking for a cinematographer to shoot Picnic at Hanging Rock. “I loved the book on which the movie was based,” Weir tells AC. “But part of its power lay in the fact it had no ending. Girls disappear on a St. Valentine’s Day picnic and are never seen again. The ending gave the story its uniqueness, but also its danger, because we had to set up such a powerful mood that the audience would not want a conventional ‘the butler did it’ ending. And to do that I needed Russell and his bag of tricks.

“The movie required more than just beautiful photography,” Weir continues. “There needed to be a power behind the images. We needed to put a spell on the audience, as it were. To achieve that, Russell experimented with various filters and nets. I remember he had silks layered in the trees like spiderwebs. We also experimented with the frame rate, shooting many close-ups at 32 fps, where the actors were asked not to blink or make sudden movements — and we cut that together with 24-fps dialogue shots. The altered speed was undetectable, but something was different, something felt a little strange.

“Russell is very specific about the best time to shoot a scene,” Weir adds. “He always reminded me of a farmer as he stomped around a location, sniffing the wind, kicking the dirt and squinting into the sun. And he was always spot-on as to the time to shoot a particular scene to create a particular mood.” For the picnic scenes in Picnic at Hanging Rock, Weir wanted a slightly magical quality. “Russ told me that, to obtain the mood I wanted, we had to film within a specific one-hour time frame,” the director says. “There was nothing to do but break up the schedule, shooting one hour a day for a full week. It created nightmares for the first AD and crew, but it was worth it for the results we were getting.”

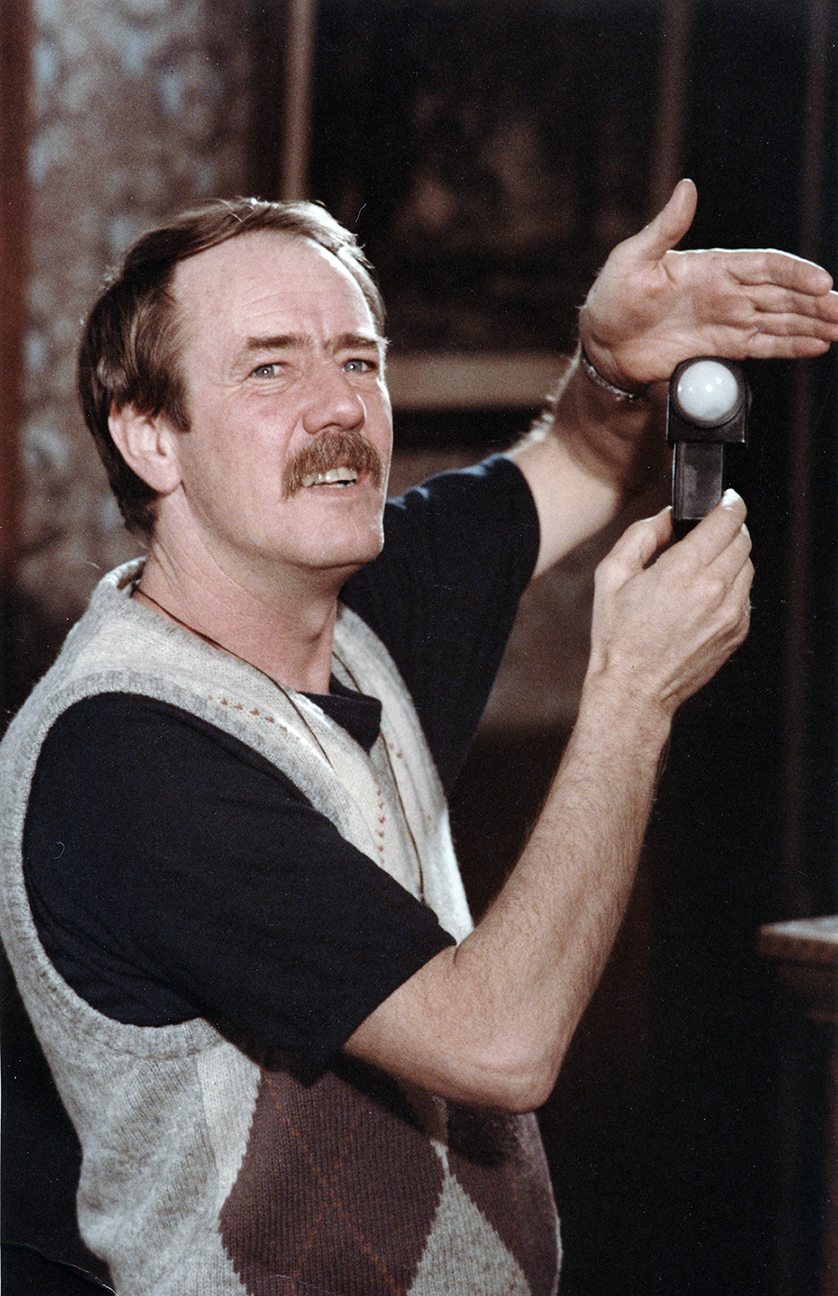

Weir asked Boyd to use a camera operator named John Seale, who had gained a reputation as the best operator in Australia, and with whom the director had worked on a TV series. Boyd gladly agreed. “Peter understood how important the operator was,” Boyd says, “and John had a huge influence on both of us.”

For his part, Seale — who, like Boyd, would also go on to become a member of both the ASC and ACS, and who has also been honored with the ASC International Award — was in awe of Boyd. After only two films, Boyd was already considered one of Australia’s top cinematographers. The two men became fast friends. “Russell always had such a wonderful demeanor about the industry and the people in it,” observes Seale. “He never lost his cool. He’d pull at the hairs on his beard, and get a funny look on his face, and say to me or the grip or gaffer, ‘Gee, I don’t think I have enough equipment to do that. What if we put this here and that there...?’ He was always a brilliant ‘make-do’ man. He accepted anything the director wanted, and found a way to make the film the director wanted, no matter what the challenges were.”

Seale recalls an incident on Picnic that occurred at the titular rock, an actual location in Victoria: “This small helicopter tried to set a tiny generator on top of the rock but missed, smashing the equipment on the rocks. A second generator met a similar fate. Russ had no lights up there. The only way he could get a nice bounce was to put up a white sheet.

“That ability to be able to compromise in your own mind as to what you have and don’t have, what you need and what you’ve got — Russ was a master at that,” Seale adds. “It’s one of the many lessons I learned from him.”

Like other cinematographers of that era, Boyd had to be resourceful, having no choice but to rely on Australia’s harsh natural light. “I started to lean toward backlighting,” he notes, “which, incidentally, was the way Impressionist artists lit their paintings.” Boyd was a great admirer of the Impressionist school of painting, particularly the Australian Impressionists of the late 19th century. “For front light,” he adds, “I would just use a big white sheet that created virtually no shadows and had a soft, rounded effect on people’s faces.”

Following Picnic at Hanging Rock, Boyd made three more films with Weir in fairly quick succession: The Last Wave, Gallipoli and The Year of Living Dangerously. The latter two starred Mel Gibson, who reflects, “We shot most of Gallipoli along the South Australian coast, in a fishing town called Port Lincoln. We also shot for 10 days in Cairo, near the pyramids, but the bulk of the backstreet stuff had to be shot indoors in a former tuna-fish canning factory. Russ is an excellent lighting man. You can’t tell we weren’t on an actual street.

“We were told we couldn’t go to the top of the pyramid,” Gibson continues, “but, before the sun came up one day, every member of the cast and crew was carting equipment up there to capture a dawn shot. We were off before the authorities knew.”

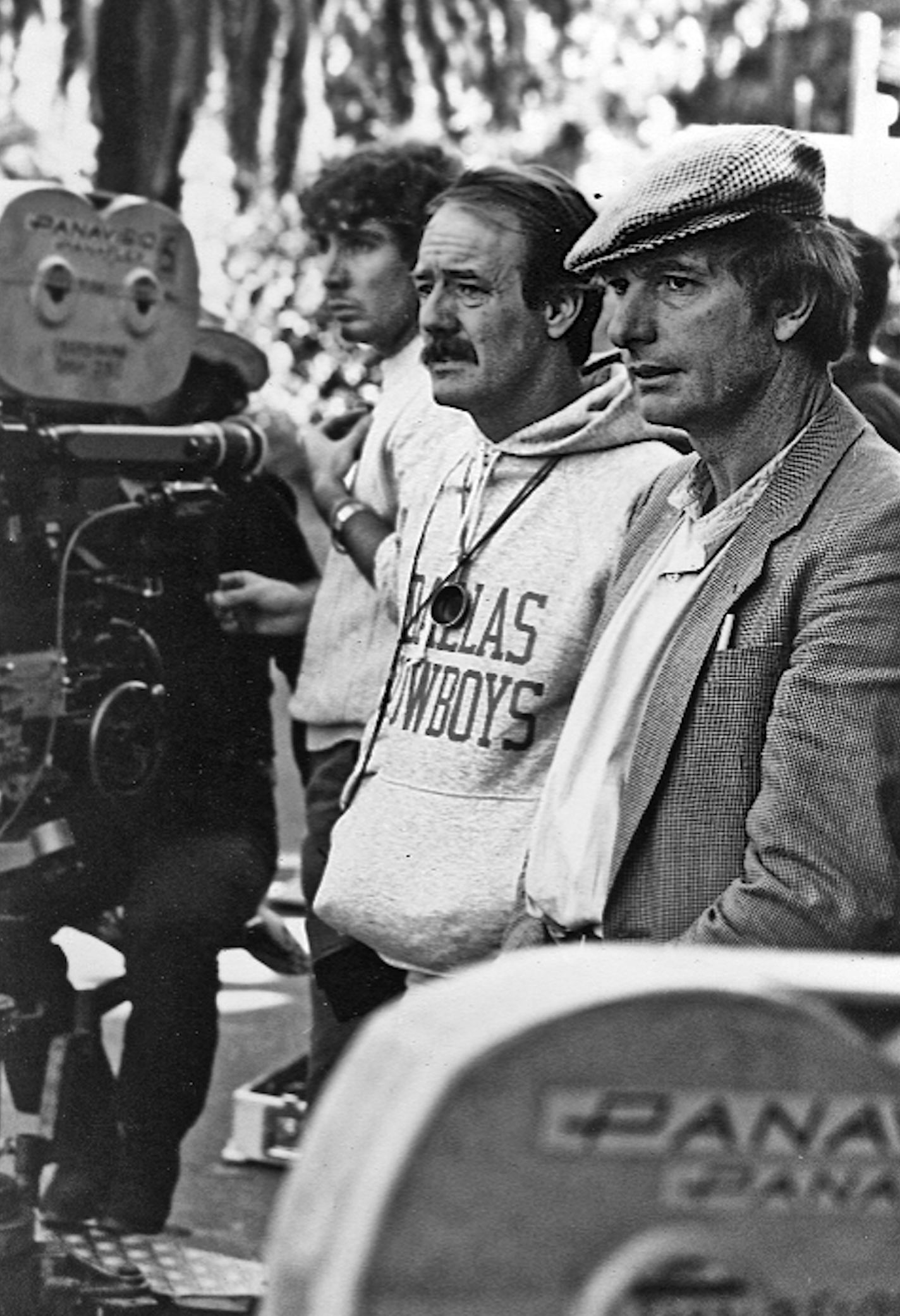

Seale, who was a cinematographer in his own right by then, took a step back in order to serve as A-camera operator on Gallipoli because he loved the project so much and wanted to be part of it. “Peter wanted these long shots of Mel running through the crowded trenches, trying to get to the officer in time to stop the attack. The trenches themselves were too narrow for us to get a profile shot of Mel, but Peter had this idea that if we put the camera in the center of a circle, with a lot of guys and a lot of activity, the camera could [simply pan around the circle in order to] stay on a close-up of Mel’s face. The circle was 30 feet in diameter, with sand hills as a background, and it looked as if Mel was running in a straight line from left to right the whole way.

“That meant, however, that the light would be changing all the way around the 360 degrees,” Seale continues. “That didn’t bother Russ. ‘Yeah, yeah, I think we can make that work,’ he told Peter — and he did! ‘To make the film the way the director wanted it’ was Russell’s creed.”

Boyd also shot four films for Gillian Armstrong, beginning with The Singer and the Dancer, a 1977 film she made as a student at the Australian Film, Television and Radio School. AFTRS opened its doors in 1973; Armstrong was one of its first 12 students. Veteran cinematographers volunteered to help the students with their final projects. “Not only is Russ a supreme technician, with a brilliant eye and a genius for light, but he has an understanding of storytelling and performance,” says Armstrong. “He is a great leader of his crew in a really quiet way; he never raises his voice. He is also a kind, generous, humble man.

“On 1987’s High Tide,” Armstrong continues, “I came up with the idea of using all these tracking and running shots, because the character Judy [Davis] plays is always running away from [responsibilities], but the producer told me we could only afford to rent a Steadicam for two days. Russ and key grip Ray Brown came up with the idea of a U-shaped bar, with two handles, to attach the camera to. Russ and Brownie then ran with the camera, tracking along low. We called it the ‘Russ-cam.’

“As for Starstruck, neither of us had ever shot a musical,” she adds. “We learned on the job. The dancers got hot and sweaty, and we realized we needed more cameras to get more angles. Russ was so smart about where to hide the cameras. Everyone thinks of him as this painterly, Impressionist guy who shot Picnic at Hanging Rock, but Starstruck was all bright colors and wonderful theatrical lighting.”

Boyd started shooting films for American directors in the mid-1980s, although he always returned to Australia when the picture wrapped. He made three films with Ron Shelton, who offers, “I always loved Russ’ work with Peter Weir, and one of my producers on White Men Can’t Jump had worked with Russ and said he was a gem of a guy. I called him in Australia, he got on a plane, and we hit it off right away.

“On Cobb, we were shooting in [Rickwood Field,] the oldest ballpark in the country,” Shelton continues. “It was in Birmingham [Alabama]. The extras’ casting people told us they’d have 8,000 extras in the stands; we got there to find only 400 extras. I said, ‘Russell, come over here’ — I was sort of in a panic. We ended up using very long lenses, just looking down the pike, and we did one [locked-off] shot, moving those 400 people 10 times. If you watch that sequence, you think there are 10,000 people!

“The trick on Tin Cup was a scene of Kevin Costner’s character walking back and forth in frustration, repeatedly hitting a ball into the water,” the director recounts. “It was the same thing over and over again. How do you make that interesting? We had to go back every day at 4 p.m. to get the light. We covered that shot from every angle.”

Tony Rivetti was 1st AC on Tin Cup, and he worked with Boyd on five films in the 1990s. “Russell had a great sense of humor and enjoyed practical jokes,” the focus puller recounts. “If somebody screwed up on the set, no matter which department, Russ would place a baseball cap with the words ‘s--- head’ on the head of the offending crewmember and take a Polaroid of it. The photo would be placed on the ‘Wall of Shame’ — which I soon realized was actually a wall of honor. It was a moment of fun and laughter.”

Gibson also remembers the cap. “The culprit’s photo was taken, and their offenses listed below. And, yes, Russ did have to wear the cap himself occasionally!”

Boyd has been the recipient of numerous awards and nominations throughout his career. He won an Oscar for his work on Weir’s 2003 film Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World (AC Nov. ’03), which also earned him an ASC nomination and a Camerimage Golden Frog nomination; Camerimage also saluted Boyd and Weir that same year with the Cinematographer-Director Duo Award. Other accolades include a BAFTA Award for Picnic at Hanging Rock, plus four Australian Film Institute Awards and five other AFI nominations.

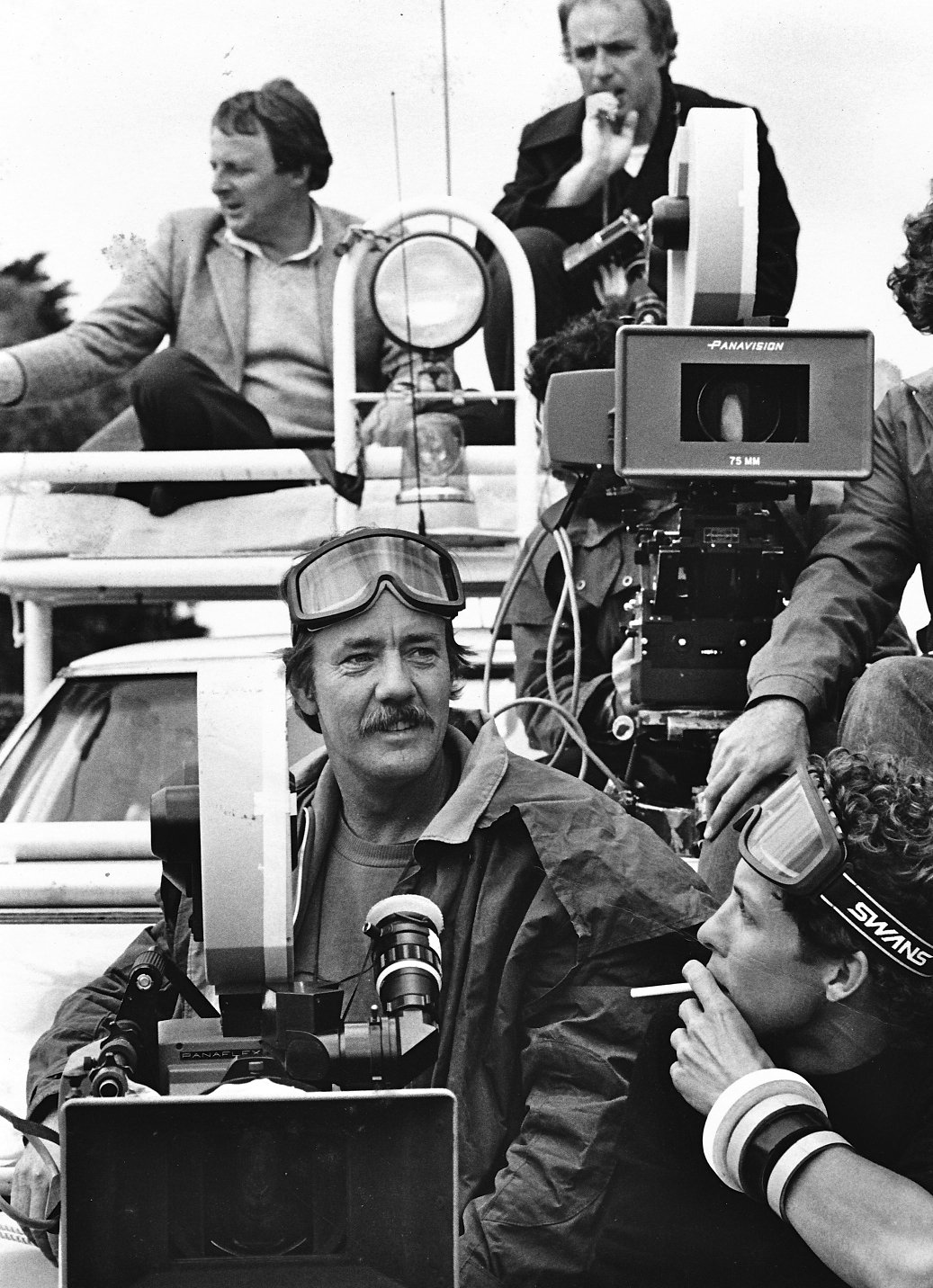

Below is a selection of production shots from Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World (2003), shooting in the water tank at Fox Baja Studios:

“Master and Commander — gee, that was a hard film to make,” Boyd acknowledges in his understated way. “There is no easy film, of course, but both Master and The Way Back [AC Feb. ’11] were very demanding physically — The Way Back because of all the snow we were working in, and Master because of the water, even though a lot of it was shot in the tank in Mexico that had been built for Titanic. In a lot of ways, though, those are two of my proudest films. Peter Weir once said to me — and I’ll never forget it — he said, ‘Come on and do a film of mine, and I’ll take you on an adventure.’ And he does!”

Reflecting on an extraordinary career that has spanned more than five decades and helped to raise the international profile of Australian cinema, Boyd muses that getting into the film industry “was probably the best decision of my life.” Asked about his worst decision, he laughs and offers, “A few films I shouldn’t have done, but I won’t tell you what they were.”

Boyd has also served as an inspiration for several generations of cinematographers. “I would often reference his work as I was learning,” says Mandy Walker, ASC, ACS. “Films such as Picnic at Hanging Rock and Gallipoli are great examples of using cinematography to represent the story and the journey of the characters. And Russ is always willing to pass on his knowledge and experiences to help out others.”

Weir picks up on that thought: “Russ is a very generous man. He is very calm, a man of few words, and a great listener. In preparation for every film, we looked at a lot of diverse material — but, as with the best collaborations, there is an empathy beyond words. That’s how it is with Russell.”

Boyd received the ASC International Award on Feb. 17 during the 32nd Annual ASC Awards for Outstanding Achievement in Cinematography. Watch Boyd's complete ASC Awards presentation video here.