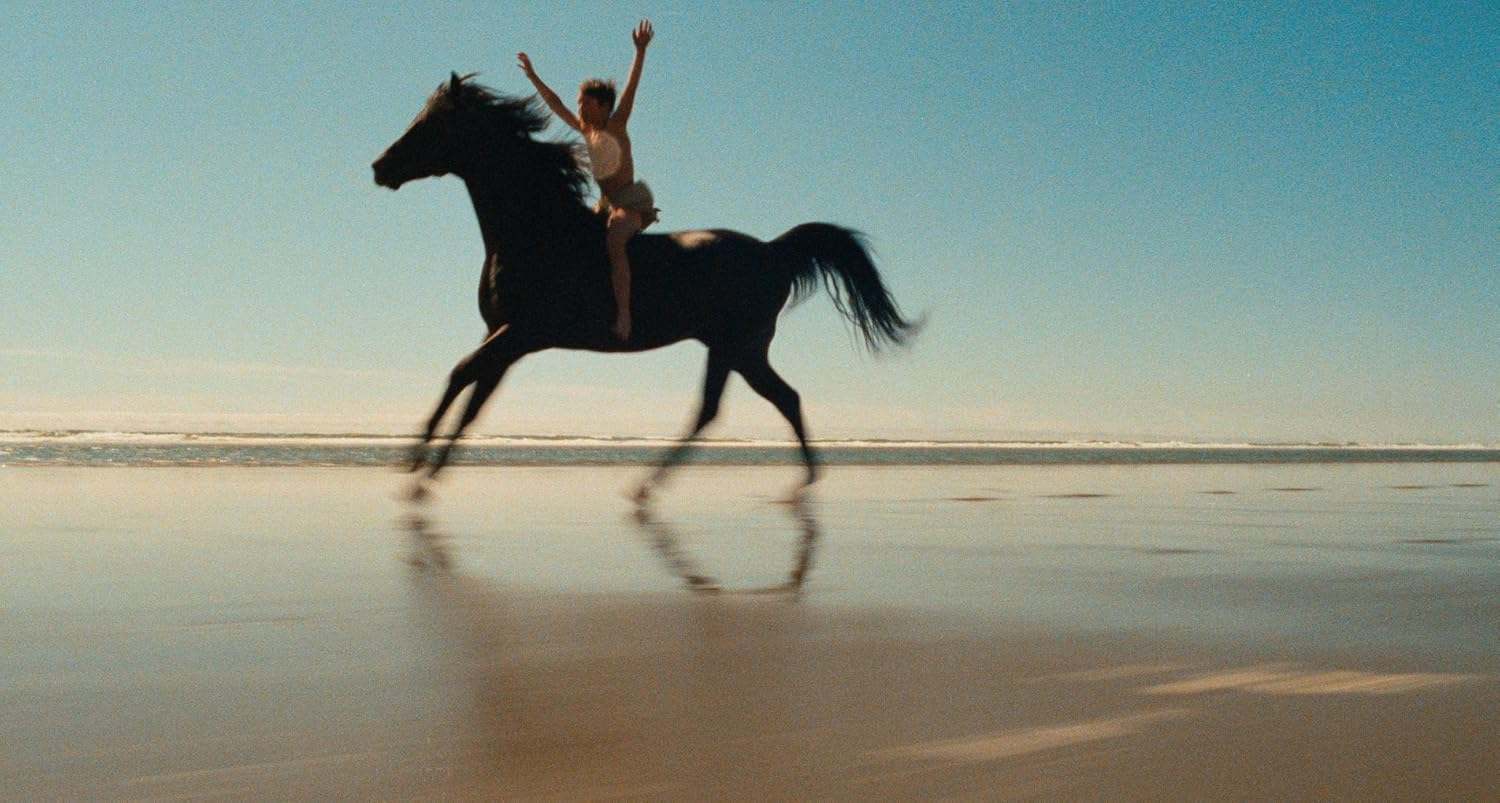

ShotDeck Drop: The Black Stallion

In this archival conversation, Caleb Deschanel, ASC details his creative and technical approaches to filming the classic tale of a boy and his horse.

Each week, ShotDeck makes hundreds of new, high-quality images available to users. AC's "ShotDeck Drops" series examines these projects with additional context and input from the cinematographers and other filmmakers involved in their creation.

Among the 1.7 million shots available from the research resource ShotDeck are selections from Caroll Ballard's 1979 feature The Black Stallion, an adaptation of the 1941 children's novel of the same name, about a young boy named Alec (Kelly Reno) who is shipwrecked on a desert island, where he forms a close bond with a wild Arabian horse. When the two are finally returned to civilization, Alec — with the help of a retired racehorse trainer played by Mickey Rooney — must find a way to tame the seemingly untamable animal.

The Black Stallion's cinematographer, Caleb Deschanel, ASC, had worked with Ballard before, on the short documentary Rodeo (1969; with Stephen Burum, ASC). "Carroll attended UCLA film school with Francis Ford Coppola," Deschanel recalled to the Camerimage Festival in 2014. Deschanel was an acquaintance of Coppola mentee George Lucas through USC's School of Cinematic Arts, and had provided additional photography for the Zoetrope Studios production THX-1138 (1971) and The Godfather (1974; shot by Deschanel's mentor, Gordon Willis, ASC). When Coppola later secured the rights to The Black Stallion, he turned to Ballard, who provided second unit photography for Finian's Rainbow (1968; shot by Philip Lathrop, ASC), and whose short films included Pigs! (1967) and one about a lost housecat, The Perils of Priscilla (1969). "Since Carroll was good with animals, Francis knew that The Black Stallion was perfect for him," said Deschanel.

A graduate of USC's School of Cinematic Arts (where he was one of the legendary "Dirty Dozen" filmmakers who were enrolled in the mid-to-late '60s), Deschanel’s cinematography career includes such memorable films as More American Graffiti (1979), Being There (1979), The Right Stuff (1983), The Natural (1984), Fly Away Home (1996, again with Ballard), The Patriot (2000), The Passion of the Christ (2004), National Treasure (2004), Ask the Dust (2005), Killer Joe (2011), Jack Reacher (2012), Never Look Away (2018) and The Lion King (2019).

His list of honors includes the 2009 ASC Lifetime Achievement Award, an ASC Award (for The Patriot), two other ASC nominations (for The Passion of the Christ and Fly Away Home), and six Academy Award nominations (for The Passion of the Christ, The Patriot, Fly Away Home, The Natural, The Right Stuff, and Never Look Away).

The following dialogue is the first half of an AFI Cinematography Seminar with Deschanel and moderator Howard Schwartz, ASC conducted for AFI Fellows at the Greystone Mansion in Beverly Hills, California, which served as the original headquarters of the AFI. It was preceded by a screening of The Black Stallion, and published in the January 1981 issue of American Cinematographer.

Howard Schwartz, ASC: Caleb, let me ask you, what kind of film stock did you use on The Black Stallion?

Caleb Deschanel, ASC: Just regular [Eastman] 5247 [100T] stock.

It had a really rich look to it. You didn’t exaggerate it in any way.

No, just used regular 85 filters. Additionally, we would use sometimes double 85s and 85s with 81 EFs, and various other orange filters.

You had a lot of gorgeous stuff. Late in the day, in the sunsets.

Because it took all day to get the horses where they were supposed to be.

I was going to say: You must have had a long schedule, and a super animal trainer.

Yes, Corky Randall was the animal trainer. His father had trained all the horses for Ben Hur. When we shot in Rome, a lot of people who were working at Cinecitta knew his father from Ben Hur; which they had done 20 years before. A lot of the credit, though, in addition to Corky, goes to Carroll Ballard, the director, because Carroll is one of these human beings who is more stubborn than any of the animals. And there were times when we were dealing with the horses, where the trainers would say, “But Carroll, they’re horses, they’re not actors. You can’t make them do these things." And Carroll would say, “No, I want it this way.’’ And he wants the horse to do a combination of actions within a shot that was very complicated and very difficult for the trainers to do. In part, because when you train a horse you train a horse to react to signals from the trainer. And there were certain ways, and he would hold up these whips that, in different patterns, would signal the horse to move back or come forward, or whatever. What happens is, if you want them to do a combination of things all in one shot, it ends up breaking part of the training for the horse, because he’ll get a contradiction of signals. So that then they have to go back in and retrain then horse. But it just took a lot of patience and a lot of determination. Mainly on Carroll’s part, because Carroll knew what he needed from the horses and just insisted on getting it. And insisted on not accepting anything less. There were times in the film when you felt that you finally had a sequence, and you’d go to Carroll and say, “Wow, we finally have it.” And he’d say, “Well, we got about 10 percent of it.” And you go, “Oh." You know you spent a week trying to get the horse to do one fantastic thing.

How long was the schedule?

Well, we started shooting in Toronto July 4th, which is the second half of the film, until about August 20th. And then we went to Rome. We did a bunch of tests, and then we went to Sardinia to location scout. And we spent about two weeks there. Then we shot from the beginning of September to December 10th.

So, you actually were six months?

Six months, yes. We were only supposed to be in Sardinia four weeks, and it ended up being seven weeks. Then we had to get back to Rome, because we had to shoot in a tank outside for the shipwreck sequence. And it was getting very cold and we wanted to get that over with. Then we came back to Sardinia again at the end, after we’d finished everything in Rome.

Another sequence that was unbelievable was the snake sequence. I’ve had a little experience in photographing them, and they don’t do anything on cue.

Yes. Horses can be trained, but snakes? You know, they know they can bite you if you get out of hand. So, I think, they don’t pay attention to what you want them to do. One of the problems we had was when the trainers brought the snakes over. There was a guy named Carlos who came over from Milan with his assistant. And he arrives on the airplane with this big leather sack, and inside the sack were three cobras. He opened them up and Carroll and I were looking at the snakes. Carroll said, “Well, now they’ve been defanged, right?" And Carlos says, “No. You can’t defang a cobra because it will make it worthless. And besides, it’ll probably die if you do that.” So, he said, “What we’ll do is, every morning we’ll milk the snakes of all the venom; then it’s much less dangerous.” He had a little cooler and inside the cooler was a little vial of this anti-venom serum and a syringe. You know, we all looked at that with great relief. We said, “Then you just get a shot, right, and you’re okay?” He says, “Well, yes, pretty much. You’d probably have to spend four to six weeks in the hospital but you won’t die." So we knew then that there was no way that we could put the boy directly near the snakes. So what we ended up doing was to get a big four foot-by-eight foot piece of glass and put it between the boy and the snake. We had to tilt it, then put a big black behind us to keep the reflections of the clouds off the glass.

And a long lens.

But what that meant was that in order to maintain the eye level of the boy, we had to dig a pit to put the camera in. So, we could operate the camera. So, there was me and my assistant and Carroll in this pit. And then there was five feet of sand and then this snake and then a piece of glass and then Kelly on the other side of the glass. So there was no glass between us and the snake.

Because snakes move so quickly my assistant couldn’t follow the focus by himself so I ended up having to do it by eye. Which is something you get real good at when you’ve done a lot of documentaries, which I had done up till that time. And my assistant spent the whole time holding onto my collar and whenever the focus got to the point where it bumped off at five feet, which was the minimum focus, and I saw this snake was coming towards me, I’d feel this yank. I would bail out of the pit and wait for the trainers to get the snake back in position.

We never got the whole sequence the first time we were in Sardinia, it was real warm when we were first there. We needed more shots, so when we came back again, we did the same setup and everything. And we put the snakes out on the sand and they just went to sleep because it was much colder. And when the sand gets cold the snakes don’t do anything. To get them to rear up and fan out the trainers would usually bop them on the back of the head. But when it was cold you’d bop them on the back of the head and they’d just sort of look up at you and then go to sleep. What we had to do was dig a two-foot deep pit and put heaters in. Then cover that up and cover it up with sand, so there was an eight-foot square section which was real warm. And the snakes would react to the warmth and would fan out and do all the acting they were supposed to do. Every once in awhile, they would slither off the warm sand and then they’d go to sleep again. And the snake trainers would bring them back onto the warm sand, then we’d try to get the shots.

How did you get the one shot, where you knew you were going to have a snake in that place coming through the bushes, because you actually anticipated the snake and panned a bit early? How did you get the snake to come on a prescribed route through the weeds there, through the bushes? You know what I’m talking about?

Yes. Well, what you have to do is you have to do it about 50 times for the snake to realize that’s where he’s supposed to go. It’s actually an accident. I mean, you want him to go there and you just keep doing it. You say to the snake, “You didn’t do it right. Go back and do it again.”

Tell us about how you and the director arrived at the basic concept of the look you wanted.

Well, the basic look, the main reasoning behind it, was to shoot a film from the boy’s point of view. We always wanted to maintain his eye level. That was the main concept. There are lots of things that I’ve read about the film, where people write about how well thought out these sequences were. And how wonderful it was. That is true to a great extent, but it’s also true to a great extent that things just happened. It was a film, at least in the island sequence that was shot, very much like a documentary. Which is the background Carroll and I both had. So it was a matter of responding to the environment. If something happened, every once in awhile the horses would run off and disappear for four hours. And you think, “Well, what can we do now?” And you say, “Well, let’s get a sea urchin and put it up here." And you have the kid look at a sea urchin.

A lot of invention happened on the set. And a lot of decisions were made behind the camera, because when you have both a boy and a horse, they don’t always hit their marks. The conflict between cameraman and actors is usually, will they hit the same place twice. It was impossible in that kind of situation. Shooting it the way we did, there was a lot of footage that didn’t get used, We shot something like 500,000 feet of film, on this film. Because you would run a whole magazine when you’re expecting something to happen. It wouldn’t happen. Sometimes four or five or six magazines, you just keep rolling and hope that the horse will come close to the boy and eat the seaweed.

A good example of what you’re talking about is an interesting sequence where he’s trying to get the horse to eat the seaweed or whatever it was, and you had him on both edges of the frame and you never knew what exactly was going to happen. When that gets shown on TV you’re going to have a big hunk of blank screen because the horse and boy are really on the outside edges of the screen.

Well, what was really awful was that when we were in Sardinia on that section of the film, there really wasn’t an existing script. In Carroll’s mind, he had the sequence of events which ultimately changed quite a bit in the editing. But we did that scene and it came out wonderfully. That night Carroll had this horrible realization that the boy was wearing the wrong outfit, because originally the boy was wearing pajamas, and through a whole series of events he ends up taking the top off. And tearing it up. And using it to build a stick man. All these things that never ended up in the film, but it was part of the sequence. So the next day, after getting this wonderful sequence, we had to go back and do it again. Surprisingly enough, it turned out as well the second time as the first time. I kept saying, “It’s never going to work the second time, we can’t get that again." In reality off to the right side of the frame was Corky Randall, waving these whips. Signaling the horse to come forward and rear up and back off. You know, as magical as it seems, it’s still a movie. There are other times where you can’t say that; you got lucky and it happened.

Looked like you did a lot of magic hour stuff at the racetrack.

Yes, we did. Well, the first ride sequence, where he rides the horse around and they’re timing it with Jake. The original concept was to do it all at night. And we debated about the idea of lighting an entire racetrack. So eventually we came up with the concept that if it was 4:00 in the morning when they started, and it came into twilight. But even with that, we ended up having about five or six cameras set up for each run, and we’d just try to get as much as we could at one time.

Let me ask: How many twilights did it take you?

Well, quite a few, because the close-ups ended up being done by Steve Burum [ASC] later at Santa Anita. All the real close-ups of the boy riding. And also, at the time the stuff that we did in Toronto, the boy wasn’t as good a rider as he became later in Sardinia. He just kept practicing and practicing. And the boy grew up on a ranch. He is not an actor. He’s just a natural. He’s a wonderful boy. And all the things you hear about working with children and being difficult was not true in his case.

He didn’t know he was supposed to be difficult.

No. He was totally enthusiastic. He always said that the only reason he wanted to do the film was to learn how to swim. And he learned how to swim in the film.

The sequence on the ship where the poker game was being played was interesting. It looked like it was done from one source overhead. The master, anyhow.

Yes, basically.

And cheated a little bit on the close-ups to help.

Yes. We did all the interiors of the ship on sets at Cinecitta in Rome. All the stuff on the ship we shot handheld to give it a little bit of movement, which gets more and more exaggerated as you get into the shipwreck scene.

That was a lovely shot where you came over his back at the poker table and around to the two of them.

Actually, that one was handheld from a dolly. So, we were on a dolly, but handholding. Because early on we didn’t want too much movement. The ship is actually a combination of quite a few different things. We shot on a real ship on the way to Sardinia. And then we had interior sets in Rome. And we had a deck exterior in the tank. The stern of the ship was also in the tank. Some of the stuff of the horse in the stateroom was on a stage, which ended up matching into exterior scenes. It’s like the close-up of when he feeds the horse the sugar, the close-ups of that were actually interior on a stage. But the wider shots in that were exterior in the tank. Just because it was easier to do. It was more difficult to get the horse on to that set in the tank.

You did a lovely job of resisting the temptation to over-light when you’re on the stage, which is a trap you can get into very easily.

That’s a nice way of saying that it was dark. Some people say it the other way, “Gee, don’t you think you could have used a little more light?” But I like it that way.

No, it had a real natural look. That was intended to be a compliment.

I know, I appreciate that. The shipwreck sequence and, I think, the night rain sequences are the ones I’m most proud of. Probably because they’re created from nothing.

Was that fun working in the rain?

Fun is not the word. First of all on racetracks, the way they’re designed is that there’s about a foot and a half of dirt and underneath there’s a clay surface, which is hard. So as soon as you add rain to it the dirt becomes mush and you’re up to here in mud the whole time. The awful thing about that was that everyday in Toronto it would rain until 5:00 p.m. So at night we had to make our own rain to create the rain sequence. You’d wake up and it’d be raining all day and you say, "Oh, great." And you get out there and you get everything set up and then it would stop raining. And you’d say, “O.K., bring out the towers and set up the rain.” So we always had to be prepared for that; for some reason it just never cooperated.

Who did the color from your original negative?

Well In Toronto it was Quinn Labs, and in Rome it was Technicolor.

Did you notice a difference between the two labs?

It’s so hard to say where the difference is. Whether it’s in the printing stock or whether it’s in the negative or the light in different parts of the world. You know, we had some problems in Rome because we were away from everything for so long. We did tests. I love Rome and I love Italy, but every once in awhile the electricity fails and the water fails. And we lost a day and a half or so of some negative over there. But then we went to Toronto. I always do real extensive tests with the lab just to see what they can do. I’ll have 15 or 20 rolls of essentially the same thing with the various different exposures that I’m trying out. You know, underexposing it, half-stop, one stop, two stops, overexposing. Then I send it to the lab and I see what they do on their own. Then I have them take that negative and if it’s not what I want I have them print it where I want it. And then, two days later I’ll send in exactly the same piece of film and I’ll see if they can duplicate it. I’ll just order up the same printing lights and see if it looks the same. Then I’ll do that at least three times and if they do it consistently three times I figure that’s the best I can hope for.

When we were in Toronto, there was a lab that had done other features, but Quinn had not done any. This other lab was sure they were going to get our business, and we sent it through and it just wasn’t there on the screen. So, we ended up going with Quinn. And they're a nice little lab. They had a real nice timer who really understood what we were doing. He was good. And in Rome, the guy who was running the lab was this guy Novelli who works with Vittorio Storaro [ASC, AIC] on all of his films and he was terrific. But the story out of that was that we had been shooting seven weeks on the film in Toronto and Carroll and I knew what we were getting, and we were real happy. The first week we shot in Sardinia we didn’t see any dailies for a whole week and then they were brought over. And we went to a little screening room in Sassari which is one of the bigger towns in Sardinia. We looked at the dailies and they looked awful. We called Novelli and he said, “Gee, your dailies looked great, I don’t know why you’re upset." And Carroll’s saying, “I wonder what they did?” It turned out to be all in projection. From then on we went back to Rome and saw them projected at Technicolor and you know, it was fine. The difference that projection can make is just extraordinary, in terms of contrast and density and focus and everything. It's just remarkable.

Yes, you’ll find not to that extent of course, but even here in this country some of the projection facilities are quite different. Getting back to the difference in labs, I’m convinced that part of the difference is in the water, it’s like with beer. In Europe, there’s a difference in the density and the quality of the light, being that it’s farther north than here in this country, and even the light on the West Coast is different from the light on the East coast.

What you’re saying is so true, and it became evident as soon as we arrived in Rome and spent a couple of days there. I kept wondering all my life how these incredible Italian cinematographers got this wonderful light outside. And you walk around Rome and you say, “That’s how they get it.” Not to diminish what they do, because they’re extraordinary in other ways, but it’s true that the light really does differ in other parts of the world.

Since this film had a minimum of dialogue, relatively, did you use wild camera equipment as opposed to sound camera equipment?

Yes. In Sardinia, we used almost all wild cameras. We had a bunch of Eclair CM-3s and the Arri 35BL for the night stuff. Fast lenses.

Did you use any zooms?

Yes. I try not to use zoom lenses, but on all the exterior stuff I used zooms. I have a real good sharp 25 to 250, which we used a lot, just because, you know with a horse, and things being unpredictable, you really want to be able to adjust your frame.

Did you use CM-3s a lot?

Most of the CM-3s have three turrets and it seems common to adapt one of them to Nikon lenses, because they’re very good lenses. For the lowlight level stuff, we used the BL, and we used the Zeiss lenses because they were real fast.

Did you do any day-for-night stuff?

No, it was all pretty much magic hour. There was some question when we were doing it, how it was going to be used. Whether we were going to treat it as magic hour or not. The rain sequence was all shot at night.

When you set up five cameras on location, was that always from Carroll’s suggestion? Or did you suggest the use of five cameras?

Well we knew we had to do it that way because it was the only way to take advantage of the 20 minutes that you get. Fortunately in Toronto it’s so far north that in the summer you really get a long twilight. So we were able to, oftentimes, get several different shots with all five cameras. As far as where we would set up the cameras, Carroll and I would both look and agree on the best spot. Sometimes Carroll would want a camera where I thought it should be over farther or whatever. Things like that are always a little bit of a give and take.

Could you talk a little bit about how you lit that night sequence with the rain? The overall color balance is real nice.

Well basically we had one arc, which we always used as backlight. In order to see rain you have to backlight it. And plus the thing about backlight is no matter how intense it is, it never overpowers the scene. So you could have a backlight that’s as bright as sunlight and it still feels like night. Then we usually used Tungsten light for all the fills. So it was a combination of real cold backlight, which essentially burns out and becomes white, and a little bluish. We went for the bluish tones. But the fill on the faces was much warmer.

Was there much difference in your dailies, how they looked color-wise in that sequence than in the final print?

No, color-wise, it’s pretty much the way it came out in dailies. The density was the thing we had questions about, probably because it is now a little bit darker than it was in the dailies. I liked it darker and Carroll ended up liking it lighter. Partly because the dailies were lighter, less dense. Bob Dalva, the editor, and his staff were all favoring the lighter because they had been working for a year and a half with these lighter dailies and that’s what they were used to seeing. So we ended up kind of reaching a compromise. At one time I had it darker than it is now. I think it’s better where it is now, partly because with so many different theaters, you have to make certain small compromises for the fact that most theaters are going to be at 10 footlamberts instead of 15 or 16, which is where they’re supposed to be. And some are at eight and six, you know.

Did you have a chance to be pretty active in the timing at all?

Oh yes. If you want to talk about something — and I think that’s a third of shooting a film — it’s getting involved in the timing. I think a lot of cameramen just say, “Well, I’ve done it," and the editors take over the timing. But a lot of decisions, particularly in The Black Stallion, were made in the editing room. Partly because the film was constructed from so many different sequences that were ultimately reduced to a smaller number of sequences. The scenes that you shot for one purpose were oftentimes used in another sequence or another section of the film. So you ended up having a sequence that was shot at midday that had to match the sunset shots that were part of another sequence. So it took a lot of work in the lab and I think it’s real important. I was fortunate enough that Larry Rovetti at Technicolor, who was just incredible, and really responsive, was able to see what we were going after. He really saved me a lot of work on the film. That makes a huge, huge difference. I guarantee I could take this film and I could make it the ugliest film you’ve ever seen. Just by making horrible mistakes in the lab. Why don’t cameramen follow through? You know the best ones do. But why they don’t, I think is crazy. There are times when you can’t, if you’re on another film and can’t get away — you try to get the lab to bring you the answer prints and the timer. Try and do it long distance. It’s not great that way, though.

I think that editors sometimes, particularly with outfits that do maybe 12, 15 pictures a year, feature pictures, the post-production supervisors seem to think that they’re the last word in timing. They get involved on behalf of the producers and a lot of times don’t bother to call the cameraman when they’re doing a timing.

I’ve been fortunate in that on all the films I’ve worked on, the producer and director have been interested in me doing it anyway. I think it’s something valuable that even if it’s not in the union contract that any cameraman who does a film should have it in his own contract. Even at that, you’re going to have the studios trying to rush it out ahead of time. At every stage you keep finding things that get done behind your back. You will know that things are not ready and you find out that somebody from New York has ordered a print. And it’s not ready, and they’re going to show it at some real important screening. And you say, “Wait a second, it’s not done." To get what you want in the labs, you have to use every bit of power at your command. If it means getting the directors and the producers to back you up. Getting them to write letters for you and getting them to get on the phone for you. You have to employ every trick that you can. At the risk of being considered a total psychotic by the people in the lab, and the people in distribution, you have to do it.

The second part of this conversation appears in the February 1981 issue of American Cinematographer. The complete AC back catalog is available to subscribers. Learn more here about how to subscribe to the industry's leading journal of motion-picture production techniques.

Founded by Lawrence Sher, ASC (cinematographer of Joker: Folie à Deux, The Hangover trilogy, Garden State), ShotDeck is the world’s largest library of fully-searchable high-definition cinematic images. With over 1.6 Million shots and now an App for iPhone and iPad access, ShotDeck is an invaluable reference, planning, and collaboration tool for filmmakers, students and creatives of any kind.