How Columbo Influenced the Cinematographers of Poker Face

From psychedelic murder sequences to the art of the long take, Poker Face's cinematographers reflect on the impact of a timeless episodic crime drama.

Much has been said about the visual and thematic similarities between the crime-drama series Poker Face — starring Natasha Lyonne as a casino worker who can always tell when a person is lying — and Columbo, the classic crime-drama series starring Peter Falk as a rumpled LAPD detective with an eagle eye and a mind like a steel trap. Besides the numerous think pieces and subreddit threads on the subject, AC ran a story on the filming of Poker Face in June 2023 — featuring series cinematographers Steve Yedlin, ASC, Jaron Presant, ASC, and Christine Ng — and the ASC produced an episode of its Clubhouse Conversations video series highlighting the cinematographers' work.

But for all the discussion about Poker Face, less information exists on the making of its spiritual predecessor, from a cinematographic perspective. A cursory investigation reveals Columbo was shot on 35mm film (likely Eastman Color Negative film 5254 100T/64D and its replacement, 5247), in the 1.33:1 aspect ratio with Panavision lenses and Panaflex cameras, and lab services by Technicolor. In-depth tomes like The Columbo Companion and (the somewhat mistitled) Shooting Columbo tend to focus more on behind-the-scenes drama, and when Columbo first aired — from 1971 to 1978, as part of The NBC Mystery Movie anthology series — AC didn't cover television productions the way it does now, even though the series was photographed by a “Who’s Who” of ASC members working in TV at the time, including Harry Wolf, Lloyd Ahern, Richard Glouner, and Russell Metty.

The initial run of Columbo — it continued infrequently throughout the '80s, '90s, and early '00s — contains some of the most inventive storytelling ever aired on network television. (Its Season 1 opener, “Murder by the Book,” is the work of a young Steven Spielberg.) Recently, AC connected with Presant and Ng, who returned for Poker Face Season 2 (now streaming), and Yedlin, who shot episodes of the Peacock show's first season, to talk about Columbo's visual style and lasting appeal.

"It’s almost more of a fantasy than a cop show, where privileged, rich assholes who believe they’re above the law are taken down by this regular guy who's simply doing his job."

— Steve Yedlin, ASC

Ng hadn't seen Columbo before working on Poker Face. "I didn’t grow up with it, because my parents aren't from the United States," she relates. "When Rian Johnson and [Poker Face showrunner] Nora Zuckerman reached out and said, 'We’re doing this show — it’s kind of based on Columbo — do you want to work on it?' I watched a few episodes. You’re totally hooked in the first 15 minutes of whatever mystery is unfolding, then the rest of the episode is about how Columbo figures out what happened. From a cinematography standpoint, what stood out for me were all these fun, optical and in-camera techniques.”

Columbo's influence on Poker Face is mostly in the formula, Ng adds. “I think nowadays, so much of what we create is a reference or homage to something. At the same time, Poker Face is very much its own thing. I never saw it as a stylistic copy or anything like that. Yes, the formula’s there, but we’re modernizing it, reworking the outcome.”

“Ransom For a Dead Man”

Yedlin wonders how much of Columbo’s style came from necessity. "Perhaps they didn’t have time to shoot extensively, leading them to rely on optical effects in post," he says. "Combine that with TV restrictions against showing explicit violence ... maybe they had to find creative ways to depict murder dramatically."

The show's second pilot episode, “Ransom For a Dead Man," is a perfect example of this, Yedlin continues. "The editing, optical effects, and music are incredibly bold. During the murder sequence, everything is either step-printed, freeze-frames, or fast flash cuts. Did they anticipate this during shooting? Some shots are carefully composed, highly designed for TV, but here, the visuals are quite standard — simple reverse shots with basic setups, like someone standing by a wall getting shot — it’s the editing and opticals that are wild.

"Maybe they only had a few conventional shots and used post-production effects to make it more dramatic, especially given TV's violence restrictions. I’m just speculating, but there are three possibilities: They fully planned it, had no plan and worked with limited footage afterward, or a middle ground where they shot basics and figured it out in post.

"It all comes down to choosing the best way to tell the story. On Columbo, they clearly didn’t restrict themselves from drawing attention to filmmaking techniques. They didn’t even insist on consistency — one episode could employ dramatic effects, while another could be totally basic. In principle, I love this approach because it’s challenging enough to craft something visually effective without imposing artificial constraints."

“Étude in Black"

Yedlin notes one especially striking visual that appears in "Étude in Black," an episode starring John Cassavetes. "During the murder, Cassavetes’ character drops a carnation from his lapel. Later, while speaking with Columbo, he notices the carnation lying under a piano. The realization is depicted through a highly unusual optical effect — Cassavetes looks over his shoulder, and the carnation suddenly appears reflected vividly in his sunglasses through a stylized optical. The effect is almost cartoon-like, dramatically out of perspective.

"I love that bold approach in Columbo because it feels authentically 1970s, not like a modern imitation. But I wouldn’t replicate that exact style today. For instance, the optical effect in the Cassavetes episode, where a window opens in his sunglasses, might feel too distracting now. I’d prefer something more subtle. Consider a similar scene in the film Chinatown [shot by John A. Alonzo, ASC], in which reflections in sunglasses reveal a key detail. There, it’s clearly an optical effect and slightly unrealistic, but subtle enough not to jolt viewers out of the story. It strikes a balance, enhancing storytelling without overwhelming realism.

"Meanwhile, the effect in Columbo isn't even meant to look real. The lack of realism isn't a failure; it’s intentional. Once they committed to using optical effects, they knew it couldn’t realistically show the carnation clearly — it had to be deliberately exaggerated. Perhaps they initially discussed realism, but realized that a realistic reflection would be too subtle. Dark glasses in a dim room wouldn’t vividly reflect the carnation. My guess is they needed clarity. Maybe they only had tight shots, and without this exaggerated visual, it wasn't clear enough that Cassavetes noticed the carnation under the piano."

Presant notes that "Étude in Black" showcases an approach often taken in Columbo — the use of zooms to isolate a detail. "The show’s all about pacing the release of information to the audience," he says. "It’s like breadcrumbs — little pieces of info dropped in consciously and specifically. You’ll have a scene rolling, and suddenly it zooms in on a small object. I see those techniques as the filmmakers trying to make the visual language more specific: 'Look here. Pay attention.'

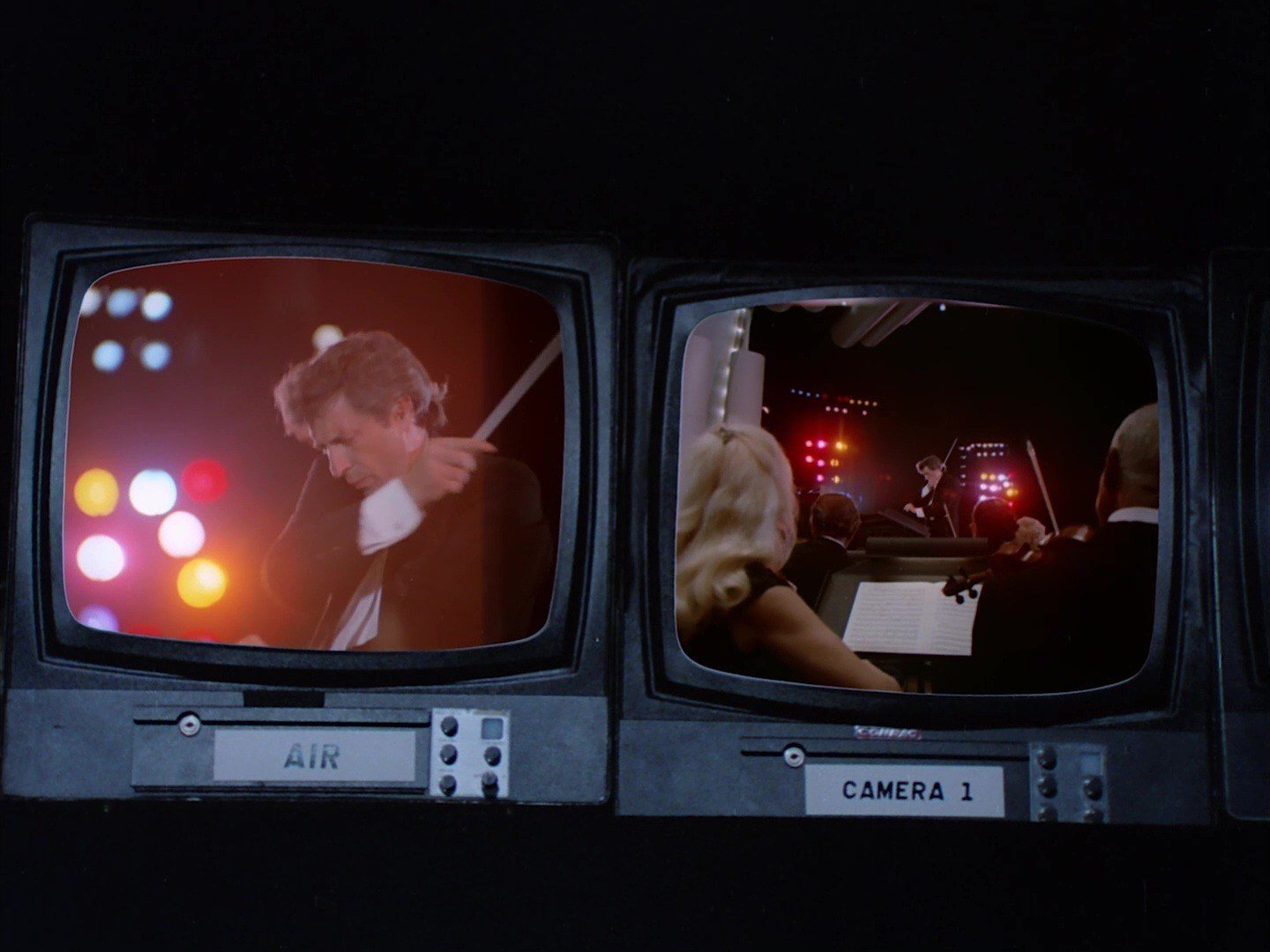

"There’s this whole visual thread throughout that episode, where the composer is being caught in frames," Presant continues. "He’s conducting on stage. Then it cuts to him on a TV monitor because the performance is being broadcast. He’s stuck in the TV. And by the end, there’s this final moment where his image is projected over Columbo. There’s something really interesting going on there with how they frame this guy, this character, and his fame — he’s caught by his fame. He is his fame. That’s what he’s protecting more than anything—his reputation, the money, the whole construct. By the end, he’s nothing more than that.

"The final scene of that episode is brilliant. Cassavettes, he’s being projected — huge — across Columbo’s back. And when you see him, he’s in half-light, just this ghost of a person. Then, he gets taken away, and Columbo’s still standing there, swallowed by that projection. That kind of contextual visual storytelling is just amazing."

“Now You See Him”

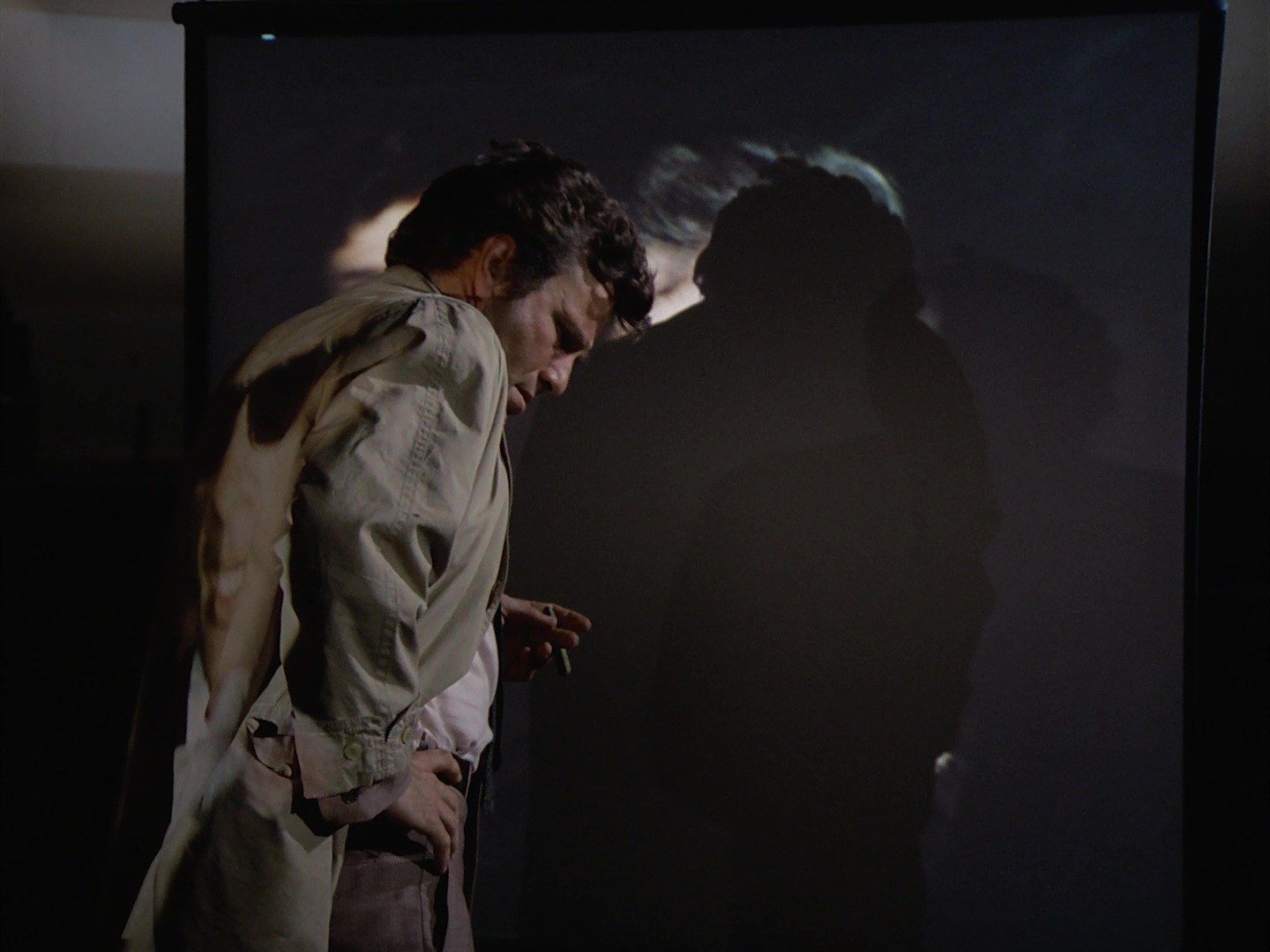

Although so many scenes in Columbo often depict Peter Falk speaking with, and studying, someone in a room, Presant stresses that those scenes are not always shot with standard coverage. "In 'Now You See Him,' there’s this recurring idea of obscured frames, shooting through things," he says. "To me, it felt like they were exploring clarity of mind, or reality versus illusion: what’s hidden and what’s not.

"That episode also introduces a younger detective [played by Bob Dishy] who’s kind of Columbo’s assistant, and there’s a scene where they’re at a locksmith, trying to figure out how a lock was picked," Presant continues. "They start the conversation inside, then they go outside and keep talking. But it’s still shot from inside, through a window. It’s like the filmmakers just wanted something in the frame — some kind of visual barrier — and it feels like they blocked the scene that way to justify the shot.

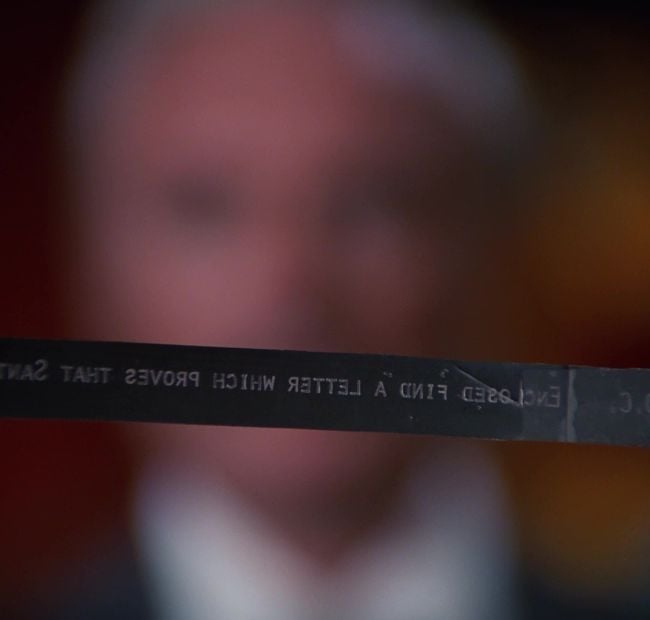

"And they do that kind of thing throughout the episode. In the final scene, it comes down to the ink ribbon on a typewriter. There’s a shot where the ribbon is in front of the magician’s face, and the camera racks focus from the ribbon to his expression. It’s this beautiful visual arc, from everything being obscured, shot through layers, to suddenly this crisp, clear resolution. That’s the kind of thing where you think, 'Oh my God, this would be so much fun to shoot.' These scripts seem simple — just two-handers — but they’re always trying to do more with them, and it’s done so subtly.

"That subtlety might have come out of necessity," Presant says. "You’re on a TV schedule, slammed for time and money. It kind of reminds me of stuff [Poker Face creator] Rian [Johnson] talks about — how to be as efficient as possible. What’s the most efficient way to tell the story? Like in that 'Now You See Him' ending: You want the audience to see the ribbon, to be able to read what was typed, but you also want to see the magician’s reaction. So, you put both in one frame. It’s efficient, but it’s also an elegant way of telling the story.

"There’s one moment in that episode — normally I get so caught up in the story that I stop thinking about the coverage, but this scene really stuck with me — where Columbo is sitting at the typewriter, and the other detective is behind him. He’s walking through what the suspect would have done, and it’s this amazing low-angle, stacked two-shot. And I thought, 'Wow, they’re just letting it play out, without cutting.'

“In our modern way on Poker Face, we try to design our shots with a certain fluidity, where they build with these little nuggets of information and then pay off.”

— Christine Ng

"At first, I assumed maybe they just didn’t shoot any coverage. That would be brave. But then, the coverage does come in, when Columbo stops talking to himself and starts explaining the scenario. When you take a minute and just let something play, you get options. It speaks volumes about the quality of the actors they had — and the courage of the directors — to just let the shot breathe." A later shot in the episode, featured in the video above, plays out for more than two minutes, interrupted only by two brief inserts.

"The decision to wait on the cut all has to do with where Columbo’s attention is," Presant continues. "That’s what’s so smart. And it’s not like they wouldn’t have shot both sides. If you’re already shooting one direction, you might as well shoot the reverse, but they chose to hold off. It’s just really thoughtful filmmaking."

Special thanks to Kino Lorber Films, who provided a copy of the remastered Blu-ray box set Columbo: The 1970s (Seasons 1-7) for research purposes. The set is available for purchase at the Kino Lorber website.