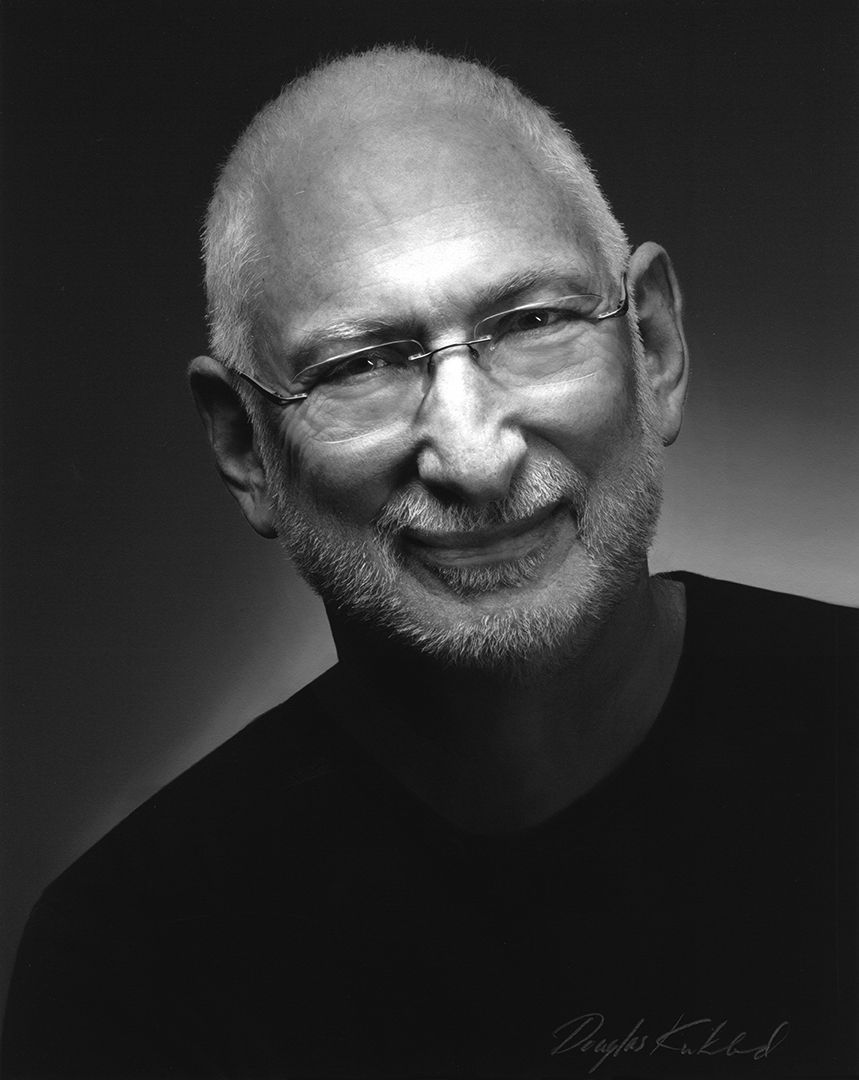

Stephen Lighthill, ASC: A Career of Commitment

Activism, art and education intersect for the 2018 ASC Presidents Award honoree.

Images courtesy of Stephen Lighthill, ASC. Portrait by ASC associate Douglas Kirkland.

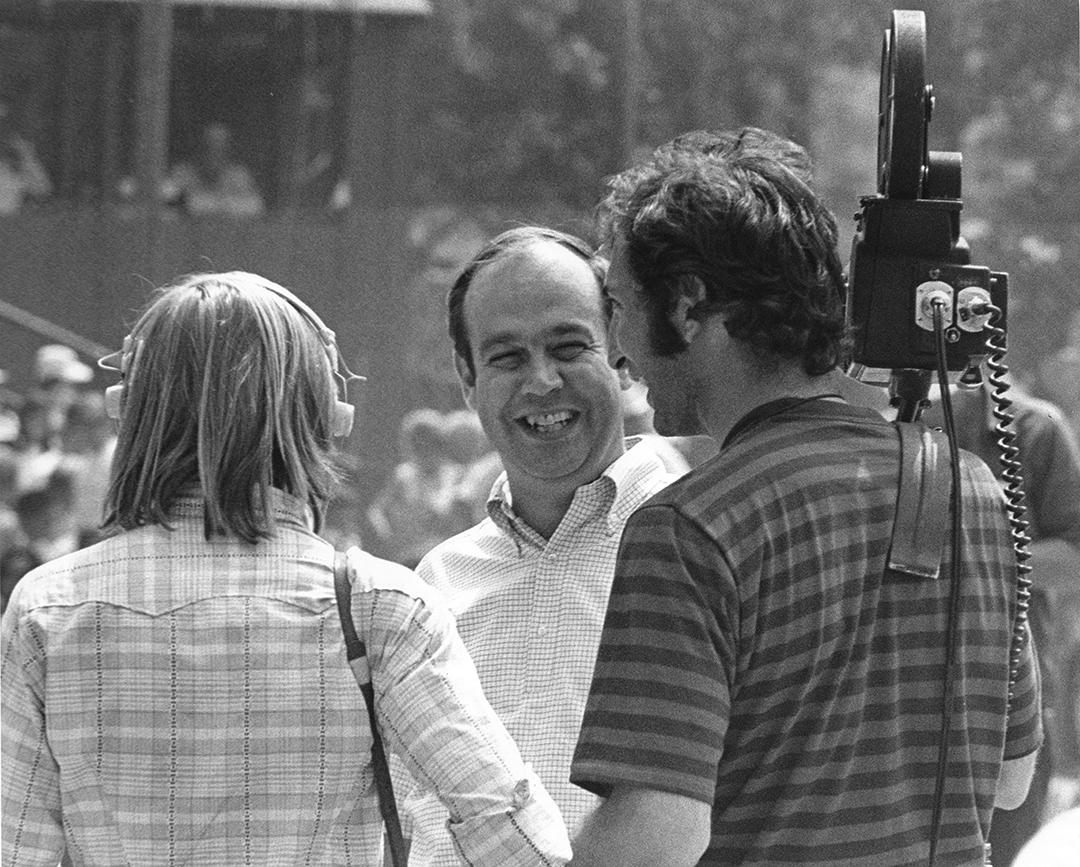

When the ASC added Stephen Lighthill to its member roster in 1999, few could have predicted the seismic changes that were about to transform the motion-picture industry, particularly the cinematographer’s craft. But Lighthill already knew something about navigating tumultuous times. He had launched his career as a television-news cameraman in San Francisco at the height of the Vietnam War and moved on to forge a reputation for skillful handheld camerawork amid the full boil of the Bay Area music scene, where he filmed such icons as the Grateful Dead, Joe Cocker, Jefferson Airplane and the Rolling Stones.

Music was a secondary love for the Connecticut native, however. A lifelong liberal, Lighthill was initially attracted to filmmaking for its potential to effect change. While earning a master’s degree in journalism at Boston University, he started attending weekly screenings on campus and “fell in love with the activist documentary filmmakers, like Pare Lorentz,” he says. “For me, cinematography was first journalism — a way to expose an injustice or right a wrong.”

He found his niche after moving to San Francisco. In 1972, Lighthill formed a film collective, Cine Manifest, with six like-minded friends: Rob Nilsson, John Hanson, Steve Wax, Peter Gessner, Gene Corr and future ASC colleague Judy Irola. Lighthill \had also made a documentary feature based around the teach-ins at Berkeley, “and it was going through the process of making a social-issue film hand-to-mouth that made me want to become a workaday cinematographer,” says Lighthill. “It was literally on-the-job training for me, and I came out of it really wanting to learn my craft properly. I also decided I wanted to reach a bigger audience. I wanted to effect change; I wanted to work in mass media. So I started shooting local news.”

He started out at a CBS affiliate by filling in for staffers on their days off. As a freelancer, he was responsible for his own 16mm camera package and lighting, and the need to research and source gear led him to American Cinematographer. “The classifieds in the magazine were a great resource, and the other ads were always instructive. When I wasn’t shooting news, I was experimenting with lighting and filters in my garage, evolving my own answers to questions. I bought the American Cinematographer Manual, and that cemented my impression of the ASC’s value as a resource.”

In 1967, through the CBS job, Lighthill gained an entrée into the cinematographers’ union (then IATSE Local 659), and he ran afoul of the notoriously closed union almost immediately. “CBS told me I could hire whomever I wanted, and when I’d hire a woman or a minority, the union would tell me I was required to hire union members,” he recalls. Over the next several years, he was a party to or a witness in three successful lawsuits against Local 659, actions that were noted and, in some instances, duplicated by many of his fellow cinematographers. Lighthill recalls, “At one of the first ASC events I attended as an ASC member, I introduced myself to John Bailey [ASC], and he said with a wry smile, ‘I know who you are. We’ve been watching your progress!’”

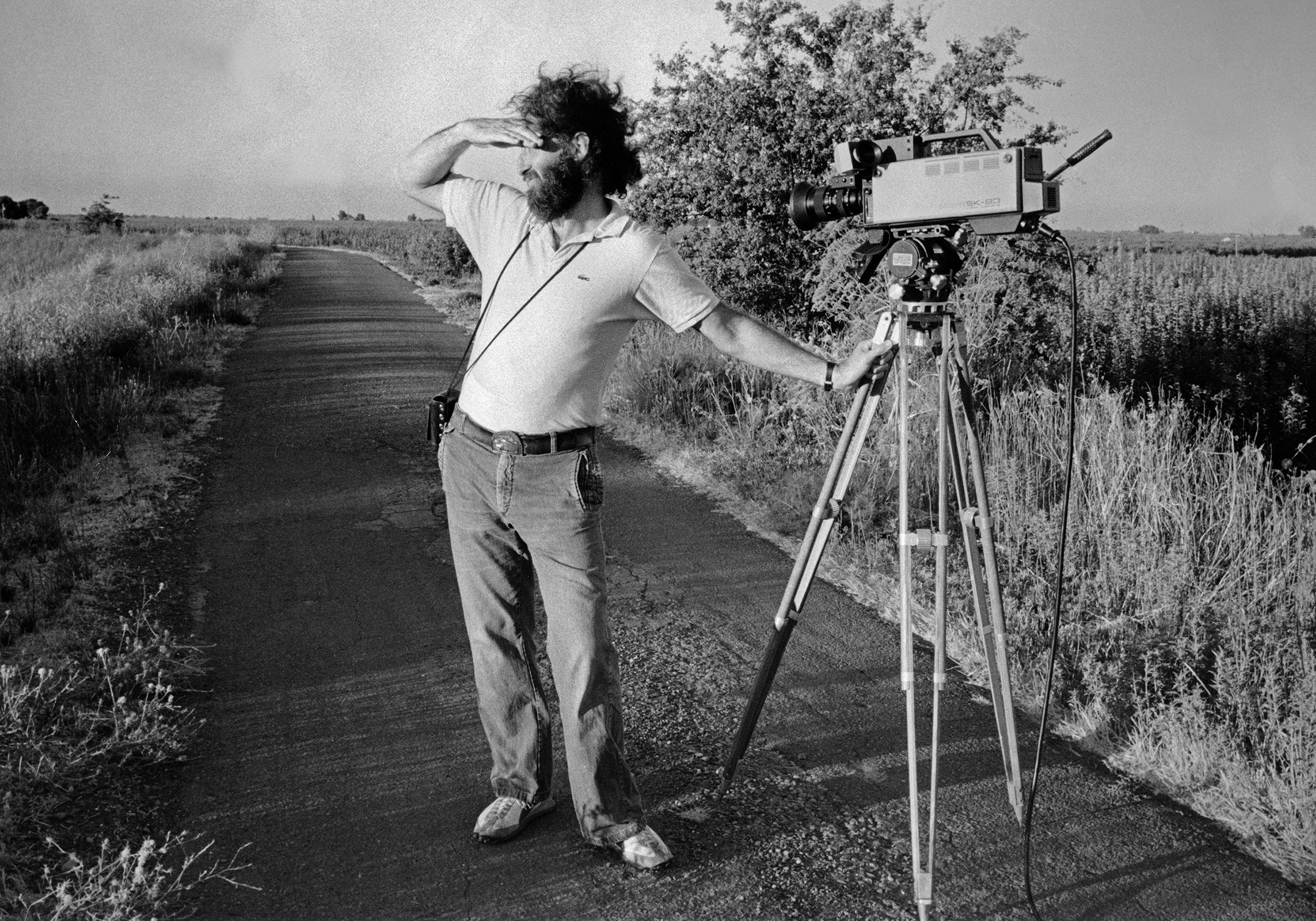

The music scene in San Francisco afforded Lighthill many opportunities to hone his handheld skills. “It was a time of tremendous musical experimentation in San Francisco, and in those days, making a concert film was seen as part of putting on a show,” he says. “We were kind of inventing the genre then. ‘Multi-camera’ meant two or three cameras, not the ‘spray and pray’ of today. Early on I shot footage of the Grateful Dead at the first Human Be-In in Golden Gate Park, and I became known as a music specialist. It took me awhile to become aware of it, though. I worked for [future ASC member] Hiro Narita, and once when he was handing out our assignments, he said to me, ‘You’re going to be onstage. You’re way better than anyone at handheld shooting.’ That surprised me!”

Lighthill credits that facility in part to growing up surrounded by music. “My dad worked in vaudeville as a composer, pianist and actor, and my sister had an extraordinary voice and won a lot of competitions, so there was always music in our house.” Another key influence was filmmaker Yasha Aginsky, whom Lighthill met shortly after moving to San Francisco. “Yasha made many wonderful ethnological music films about blues players and folk musicians, and working with him taught me how to break down the music and cover it.”

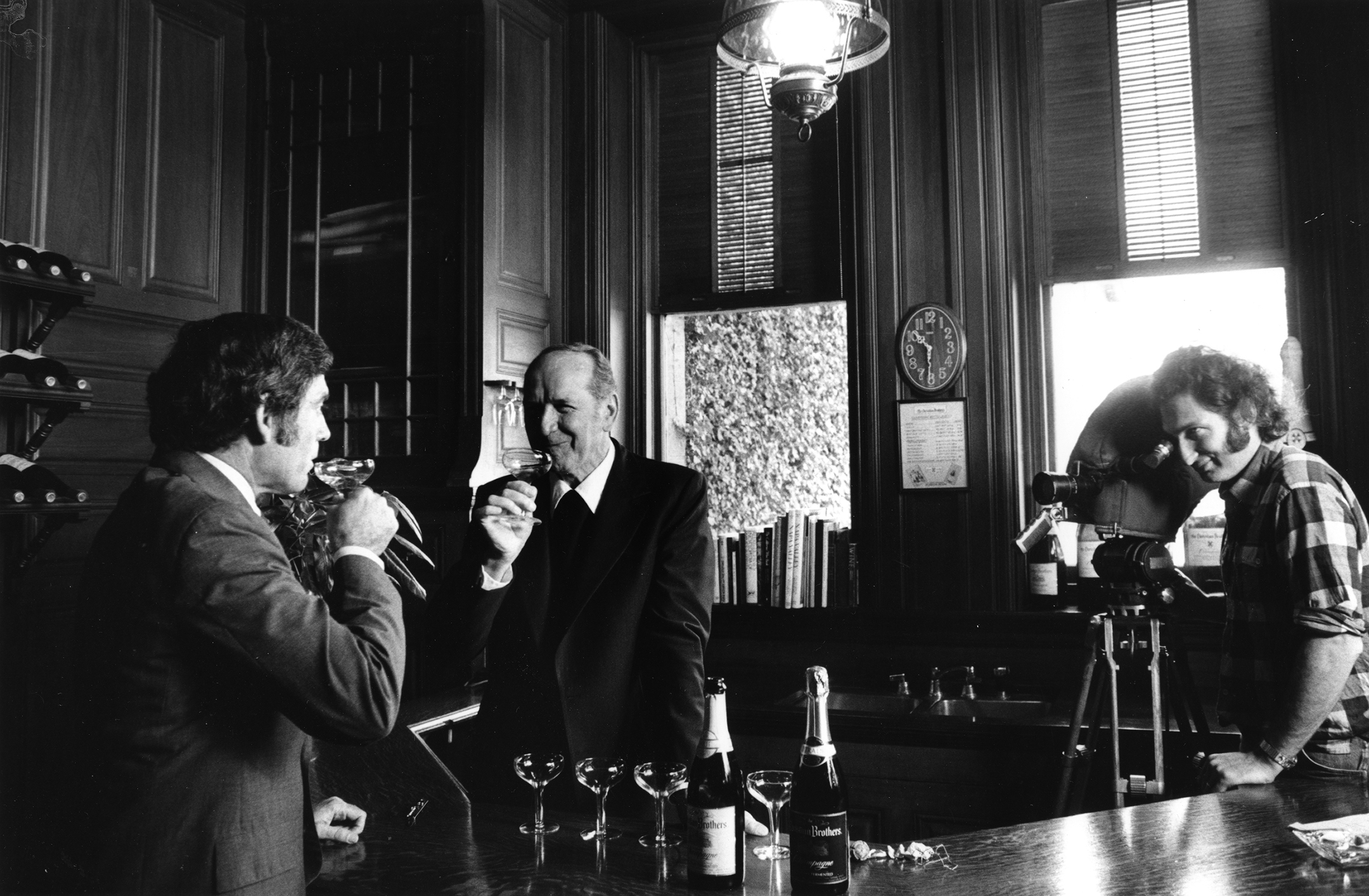

The concert film Gimme Shelter, which covered the infamous Altamont Speedway Free Concert in 1969, was Lighthill’s first opportunity to shoot for Albert and David Maysles, and he notes that his choice of camera package on that fateful day had a lot to do with the position he was assigned. “My documentary camera was an Éclair NPR, but I was kind of a freak about getting the latest lenses, and I had a new 9.5-to-95mm lens on my news camera that I really wanted to use. My news camera, an Auricon Conversion, required a shoulder brace and a heavy battery, and I had to view through a 7-inch side finder that stuck out toward the back of the camera.”

“The Maysles wanted us to go out in the crowd, find interesting characters and tell the story of that day through those characters, but when David saw my big, bulky camera, he said, ‘Why don’t you go up on the stage?’ Of course, all the drama that evolved at Altamont happened onstage. I was stage right, and I’d flip up my viewfinder so it didn’t look like I was rolling the camera; I’d look in one direction and the camera could point 90 degrees in the other direction, so I could film surreptitiously.”

Regarding his shooting experience on The Grateful Dead Movie (1977), filmed during a series of concerts in 1974, Lighthill recalls, “[Concert promoter] Bill Graham hated cameras and the idea of concert films, but the band wanted this movie made. They wanted me next to Jerry Garcia, but Bill didn’t want me to block anyone’s view. He said, ‘You can cut a hole in the stage, and you can come up through that hole no higher than your shoulders.’ I spent four nights in that hole, filming the band from the world’s worst angle! They actually cut holes on both sides of the stage, so I’d run back and forth under the stage and pop up in each one!”

From the mid-1970s to mid-1980s, Lighthill dedicated himself to shooting a variety of nonfiction projects. “I was tired of shooting cinema vérité and seeing it reduced to touchdowns and body counts for TV news. I wanted to shoot long-form documentaries.” His work during this time included the Academy Award nominee Seeing Red, about the American Communist Party, and NBC White Paper documentaries. “Those [latter] projects were my cinematography grad school because I learned about life and politics and the American West. We were a crew of three, and we’d finish shooting in Boise, for example, and then turn in our return plane tickets, rent a car and drive back to San Francisco. It was also my grad school in that I was shooting a lot of interviews and learning from my mistakes. I learned portrait lighting the hard way!”

In 1985, he landed a job operating on On the Edge, a feature about a professional runner (played by Bruce Dern). “Rob Nilsson was directing, [future ASC member] Stefan Czapsky was the cinematographer, and they needed an operator who could do a lot of handheld and keep up with Bruce,” he explains.

“I learned a lot from Stefan, and one of the things he taught me was that the job of the cinematographer is to give bad news to people all day long, but do it in a way that keeps everybody calm. The instructive moment was when we were shooting a scene on Mount Tamalpais that required Bruce Dern to stop running and jump into a pond. I was on a rig out over the water, and Bruce got in the water and did the scene. He was almost blue; it was freezing cold. Stefan asked me, ‘How’s the shot?’ And I said, ‘Well, it’s not perfect. Here’s what happened…’ and Stefan said, ‘Look, the bottom line is it’s not right, and we have to get it right.’ I said, ‘But Bruce is freezing,’ and Stefan said, ‘That’s not your concern. You just have to tell me if it’s right.’ So I said, ‘No, it’s not right.’ Stefan walked over to Rob and said, ‘We’re doing it again.’ We did it again and got it right. I learned then that your job is to serve the story, and part of that is telling people exactly what you think about what you’ve shot.”

In the mid-1980s, when new leadership and the cumulative effect of years of litigation brought a turning of the tide in Local 659, the union opened up, and Lighthill jumped in to help. George Spiro Dibie, ASC, who was elected Local 659 president in 1984 and served in that capacity for more than two decades, recalls, “When the membership finally agreed to open up to young, talented camera crews, Stephen became my right hand in educating our new members. He is equally devoted to his craft and his many colleagues; I’ve never seen someone so dedicated. When [International Cinematographers Guild] Local 600 was created [in 1996], I asked him to train our members on a national scale.”

“Sometimes someone tells you something about yourself that surprises you,” says Lighthill, “and someone on a film crew once said, ‘You’re a great cinematographer, but you’re an even better teacher. You should be teaching.’ I started teaching part time very early in my career, and I always enjoyed it.”

Keen to move into narrative filmmaking, Lighthill relocated to Los Angeles in 1987. “When you move to L.A., you give up all your connections and become a nobody in this huge place,” says Bob Primes, ASC, who befriended Lighthill in the early days of their careers in San Francisco and preceded him in making the move. “Almost everybody in L.A. has made that transition at some point, but it’s not easy. I was 35 when I made it; Steve was a bit older. He was an honest filmmaker with a lot of integrity. He was scratching into drama from a background in documentary.”

In 1994, Lighthill landed his first primetime cinematography credit on the series Earth 2, which lasted one season. “I loved the cast and the stories, and it was heartbreaking for me that it didn’t succeed,” he says. Nash Bridges and other projects followed, but he soon began to feel it was time for another transition. “Primetime drama was initially a lot of fun, but after awhile I found I didn’t like the scripts I was shooting. Content has always been key for me; I got into the business because I wanted to tell important stories about people. Throughout my career there was some tension with that, and by 2000, I felt I wasn’t doing what I wanted to do with cinematography anymore.”

Teaching beckoned, and Lighthill began serving as an adjunct instructor at the University of Southern California and the American Film Institute. In 2001, Bill Dill, ASC, chairman of the cinematography program at AFI, offered Lighthill a full-time faculty position, and three years later, when Dill decided to move on, he successfully advocated for Lighthill to become the new chair, a position he still holds. “A great cinematographer isn’t necessarily a great teacher,” Dill says. “Impressive credits are one thing, but you have to have an affinity for communicating an idea to someone else. Stephen has all that. Before I even met him, I knew from his work that he was a person of conscience, and I respected that. He also had a reputation for being both knowledgeable about his craft and mindful of filmmaking’s larger place in society, and that was key. AFI’s student body is uniquely international, so I felt it was important to hire someone whose perspective of the world went beyond ‘the business.’ I had a feeling Stephen would excel at AFI, and boy, was I right!”

Preparing cinematography’s next generation for what lies ahead is “a remarkable opportunity,” says Lighthill. “During the past decade, cinematography has transformed from being photochemical-based to being almost exclusively electronic-based, and we have tried to find the right balance in our curriculum. In the process, I’ve learned a lot about how people learn, and helping them do that has been an enormously rewarding thing.”

Which three films does he recommend all his students see? “The Diving Bell and the Butterfly, because it’s a fully developed narrative with very little dialogue and a very effective example of point of view; Ida, because it’s such a gripping story and the composition is so beautifully knit into the telling of the story; and Gimme Shelter, because I have to have a documentary in there somewhere, and that’s a schizophrenic film that was transformative in my life.”

Lighthill continues to volunteer his time to both the ASC and the ICG. He serves on the governing boards of both organizations and has done so for many years, and he served as president of the ASC from 2012-’13. “I think my career has been as much about the cinematography community as it has been about cinematography itself,” he observes. “Through my work with the ASC and the guild, and now through teaching, I feel very rooted to a community of people who care about cinematography and its future.”

Indeed, in honoring Lighthill with its Presidents Award this year, the ASC salutes a cinematographer who embodies its motto — “Loyalty, Progress, Artistry” — to a singular degree. Just don’t expect him to admit it. “Stephen once said to me, ‘You know, I didn’t have a real shining career,’ and I was so taken aback,” Primes says. “When you look at all he’s done and all he continues to do, you realize what a humble observation that is.”

UPDATE: Watch Lighthill's complete ASC Awards presentation video here.