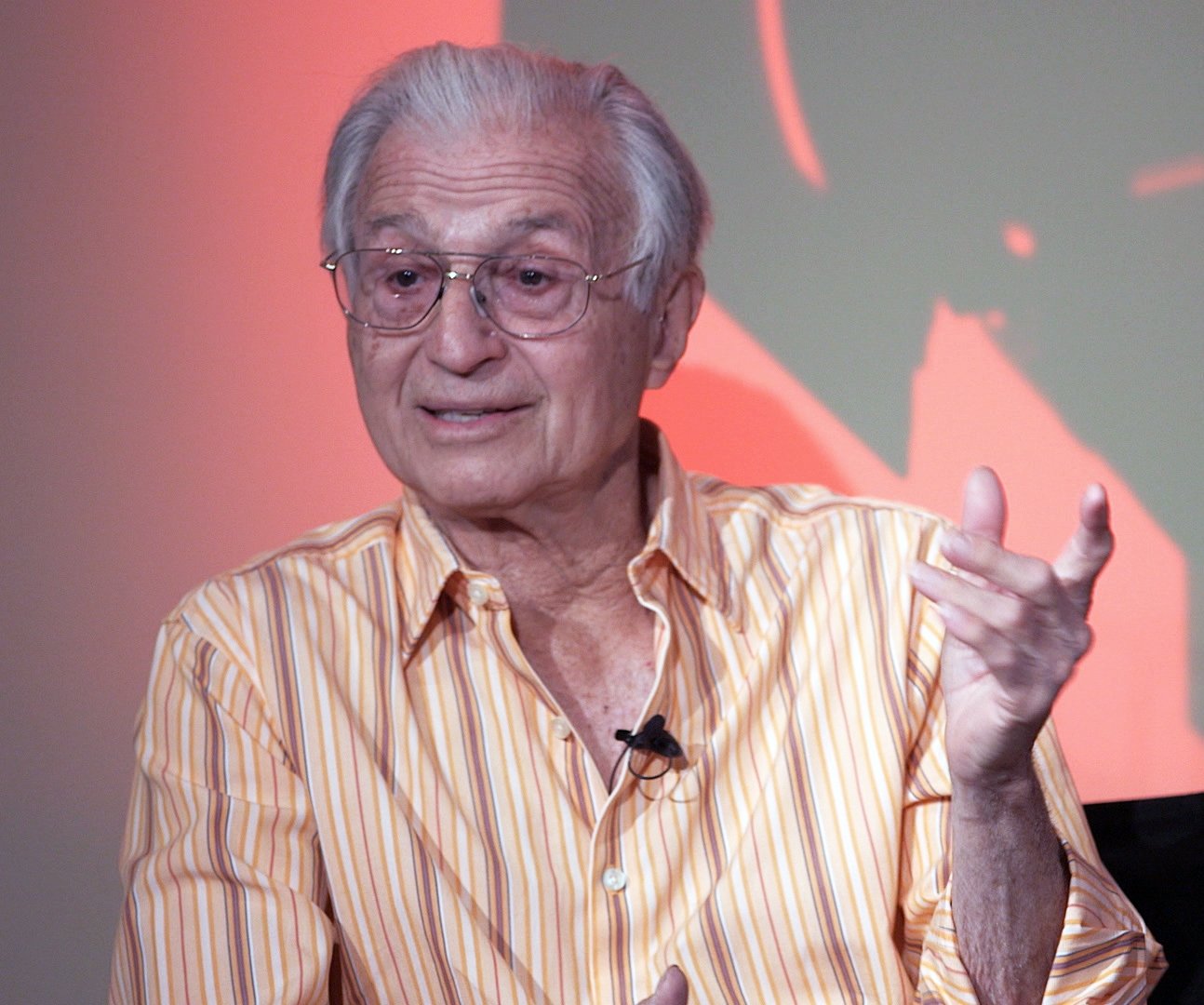

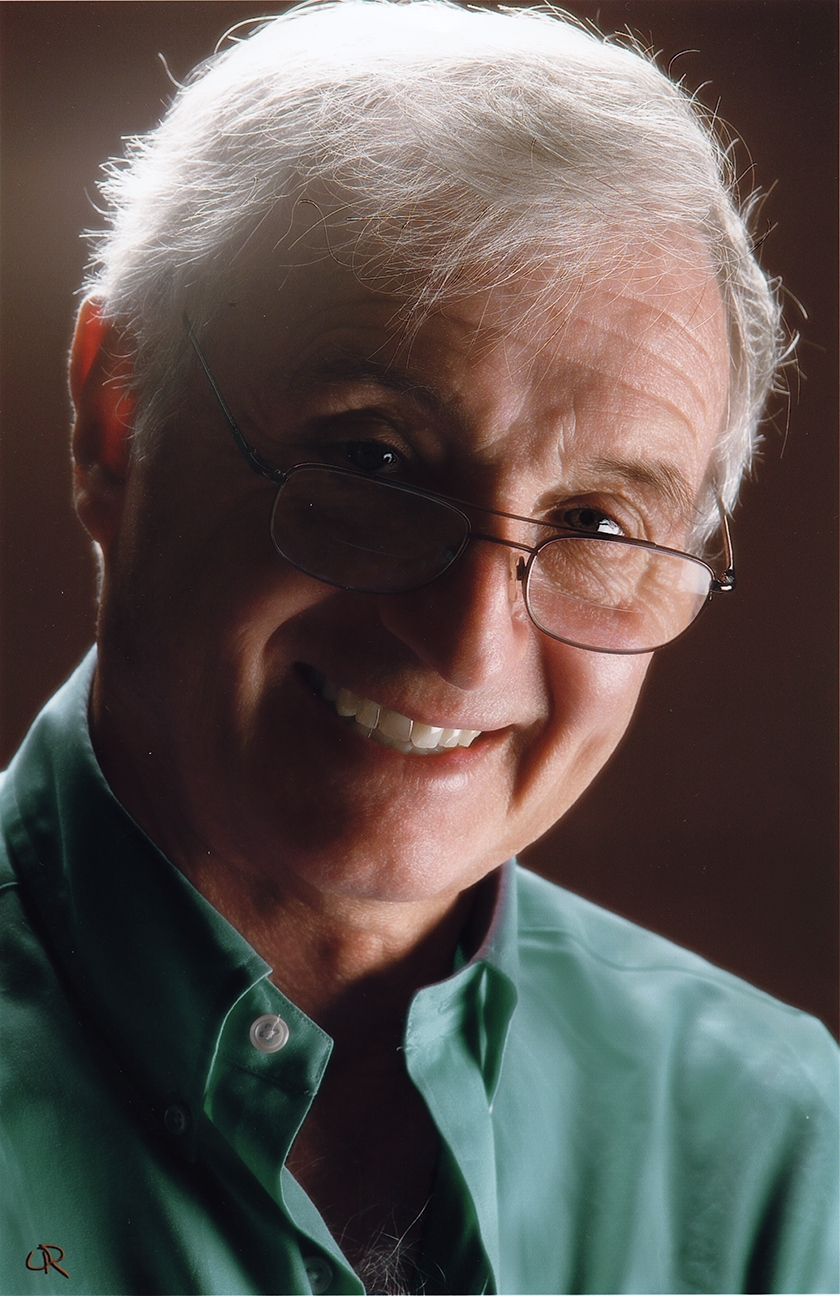

Victor J. Kemper, ASC — A Fitting Candidate for Kudos

The American Society of Cinematographers salutes his exceptional career with its 1998 Lifetime Achievement Award.

Editor’s note: This profile was originally published in AC Feb. 1998. Kemper died at the age of 96 on Nov 27, 2023. A full memorial piece will soon be available.

Over the past 27 years, director of photography Victor J. Kemper, ASC has compiled 52 major feature film credits. His eclectic body of work ranges from stark drama to outrageous comedy, and includes such diverse titles as Husbands, They Might Be Giants, The Candidate (see AC Sept. 1972), The Last of the Red Hot Lovers, Dog Day Afternoon, Stay Hungry (AC Feb. '76), Audrey Rose, Slap Shot, Oh God!, The Jerk, The Four Seasons, Mr. Mom, Pee Wee's Big Adventure, Clue (AC Jan. '86), Author! Author!, See No Evil, Hear No Evil(AC July '89), Beethoven, and Jingle All the Way. In honor of his career efforts, the American Society of Cinematographers has named Kemper the recipient of its 1998 Lifetime Achievement Award.

"This award is given to an individual who has made substantial and unique contributions to advancing the art of cinematography," says former ASC President Owen Roizman. "I can't think of anyone who is more deserving. Victor is an amazingly talented artist. Many cinematographers can point to 5, 10, or 15 good or great films where they made important contributions. Victor has done it year after year."

Kemper will be honored at the 12th Annual ASC Awards event, to be held on March 8 at the Century Plaza Hotel in Los Angeles. With this prize, he joins a distinguished club of previous Lifetime Achievement Award winners: Roizman, Sven Nykvist, Gordon Willis, Conrad Hall, Haskell Wexler, Philip Lathrop, Charles Lang, Stanley Cortez, Joseph Biroc and George Folsey.

Kemper is the third Lifetime Award recipient in the past four years who launched his career in New York during the 1960s. His path to Hollywood was a circuitous one. Born and raised in Newark, New Jersey, he claims that he never went to the movies as a kid, except for Saturday afternoon serials. Instead, his interests lay in such activities as building radios. As a teenager, he earned pocket money by repairing neighbors' malfunctioning television sets. After graduation from Seton Hall University, Kemper worked at a local TV station, where he operated a sound boom, mixed sound, repaired cameras and served as a floor manager and technical director on studio productions.

When the station was sold, Kemper went into business with a cousin, running a Florida hat manufacturing factory. He then took a position at a paint and lacquer manufacturing plant. Subsequently, however, the manager of his local TV station requested that he return to Newark.

In 1954, Kemper heard that Ampex had invented a two-inch black-and-white videotape system which was being touted as a replacement for film. When the company offered a two-week training course at its corporate headquarters in Redwood City, California, he asked the station manager to fund his trip. After the station reneged, Kemper quit his job and paid his own way to Redwood City. It was quite an audacious move for a young person with very little money, but Kemper was looking towards the future. He believed that Ampex's system marked the beginning of film's demise. In fact, Daily Variety announced the invention with the gigantic headline: "Film Is Dead?"

Kemper soon found himself in the unique position of being the only freelancer in New York City trained to use the new Ampex system. He was hired by EUE, the city's top TV commercial production company. Feature-film cinematographers from around the world were then shooting EUE spots, but when Screen Gems purchased the company a few years later, the video department was eliminated. With the aid of a financial backer, Kemper and an EUE staff director purchased a quarter of a million dollars' worth of video hardware for $70,000. In a moderately successful venture, they produced commercials and duped tapes for about two years. But when their financial backer suffered a heart attack, business was closed.

Several cinematographers who had met Kemper at EUE put him to work as an assistant cameraman. He quickly advanced to become a camera operator for Arthur Ornitz, ASC. Kemper initially worked on commercial crews; his first narrative experience was as an operator for Ornitz on the 1964 ballet film A Midsummer Night's Dream, performed by the New York City Ballet. During the next several years, Kemper worked as a camera operator with Ornitz on The Tiger Makes Out, Charley and Me and Natalie, and with Michael Nebbia on Alice's Restaurant.

These jobs provided Kemper with seminal experiences. Ornitz himself was a minimalist in his use of artificial light. "Arthur believed that the fewer lamps you used, the better it was because that gave you freedom to move the camera without creating shadows that couldn't be accounted for by natural light," recalls Kemper. "I was much more interested in understanding why he wanted a particular look than in how he achieved it. I also watched how he related to people, including directors, actors and his crew, which is a big part of the job."

Kemper's breakthrough came in 1969 when he was hired to be the standby cinematographer in New York for Aldo Tonti, a talented Italian cameraman who was slated to shoot Husbands for John Cassavetes. Kemper was reluctant to take the job because he was riding a hot streak as an operator and didn't want idle time. But when the producers promised him that there would be a lot of second-unit work, he decided to sign up. Kemper started on a Tuesday, but by Friday he had yet to shoot a single frame. He informed the production office that he wouldn't be back on-set come Monday. That night, Kemper got a call asking if he could meet with Cassavetes. Kemper had invited Tonti to spend the weekend with his family at their New Jersey vacation home, but he agreed to meet Cassavetes at 9:15 a.m. the next morning.

“Great cinematography has to be unobtrusive. It should never call attention to itself. You are there to help the director tell a story.”

— Victor J. Kemper, ASC

Kemper arrived early. Five minutes before he was scheduled to meet with the director, Tonti walked out of Cassavetes' office. Tonti and Kemper chatted briefly, arranging to meet later. Then, with no preliminaries, Cassavetes asked Kemper to shoot Husbands. Kemper was stunned; Tonti was a world-famous cinematographer, but Cassavetes explained that the two of them couldn't bridge the language barrier. Later that day, Tonti assured Kemper that it would be okay for him to accept the offer.

"We shot more than a million-and-a-half feet of film during 10 weeks in New York and 12 weeks in London," Kemper says. "That's the way Cassavetes worked. The first shooting day was on a bathroom set that the designer had painted black. Only the fixtures were white. There was also a mirror. The male characters, in mourning for a friend who had just died, were all wearing black. I had the challenge of making black costumes against a black wall visible. There was no contrast. I asked John 'How on Earth am I supposed to light this set?' He answered, 'Why are you asking me? You're the cinematographer.'" Kemper solved the problem by using hotter-than-normal back- and sidelight, which created enough separation between the dark costumes and the wall.

Kemper's second film and his first comedy was They Might Be Giants, starring George C. Scott in the role of Sherlock Holmes and Joanne Woodward as Watson. "We had wrapped production and spent every dime in the budget," he remembers. "The production manager called one day and said, 'We have a serious problem. We never shot any title footage.' He asked if I could do something without a crew."

Kemper told the prop man about the dilemma, and asked him to bring some lab equipment test tubes, vials, vessels, flasks, tubing and burners to his home in New Jersey; the cinematographer had promised his family he wouldn't work for a few weeks, so to keep this agreement he decided to shoot the title background footage at home. General Camera delivered an Arriflex camera and lenses. Kemper put some plywood on top of his bed, and the prop man set up the glassware. They filled the tubes and flasks with bubbling water colored with different vegetable dyes. To create atmosphere, Kemper also used smoke and shot from "weird" angles. "I think it cost around $700 to shoot the background for the titles," he says, "and it was appropriate because Sherlock spent a lot of time in the lab."

The following year, Kemper shot Who Is Harry Kellerman and Why Is He Saying All Those Terrible Things About Me?, working with visual-effects supervisor Joe Westheimer, ASC. A portion of the picture demanded bluescreen matte work, necessitating that the two work closely together on certain sequences. Kemper arrived early for the first day of matte shots, and although he had never before done bluescreen photography, he began properly balancing the light on the screen until Westheimer's arrival. The dailies were perfect. Impressed, Westheimer checked on Kemper's previous pictures and, in 1971, nominated him for ASC membership. "It was an unbelievably emotional feeling to be invited to join the ASC, because the members were icons to me," remembers Kemper. "I'll always be grateful to Joe."

Kemper's roundabout career path finally led to Hollywood. "I never walked onto a soundstage in Hollywood until I shot The Last of the Red Hot Lovers at Paramount in 1972," he says. "It was a lot different than shooting in New York, where we didn't have Brutes, heavy-duty grip equipment and big trucks with everything on them. We had learned to work with less because it was the only way we could work. We shot The Last of the Red Hot Lovers for about 2 1/2 weeks in Philadelphia and then moved to Los Angeles. Lloyd Ahern Sr. [ASC] was my standby cameraman, just as I had been a standby for Aldo Tonti."

“Cinematographers aren’t responsible for scripts or the tenor of stories, but if I accept a job I also accept responsibility for realizing what kind of influence it might have on the people who watch it.”

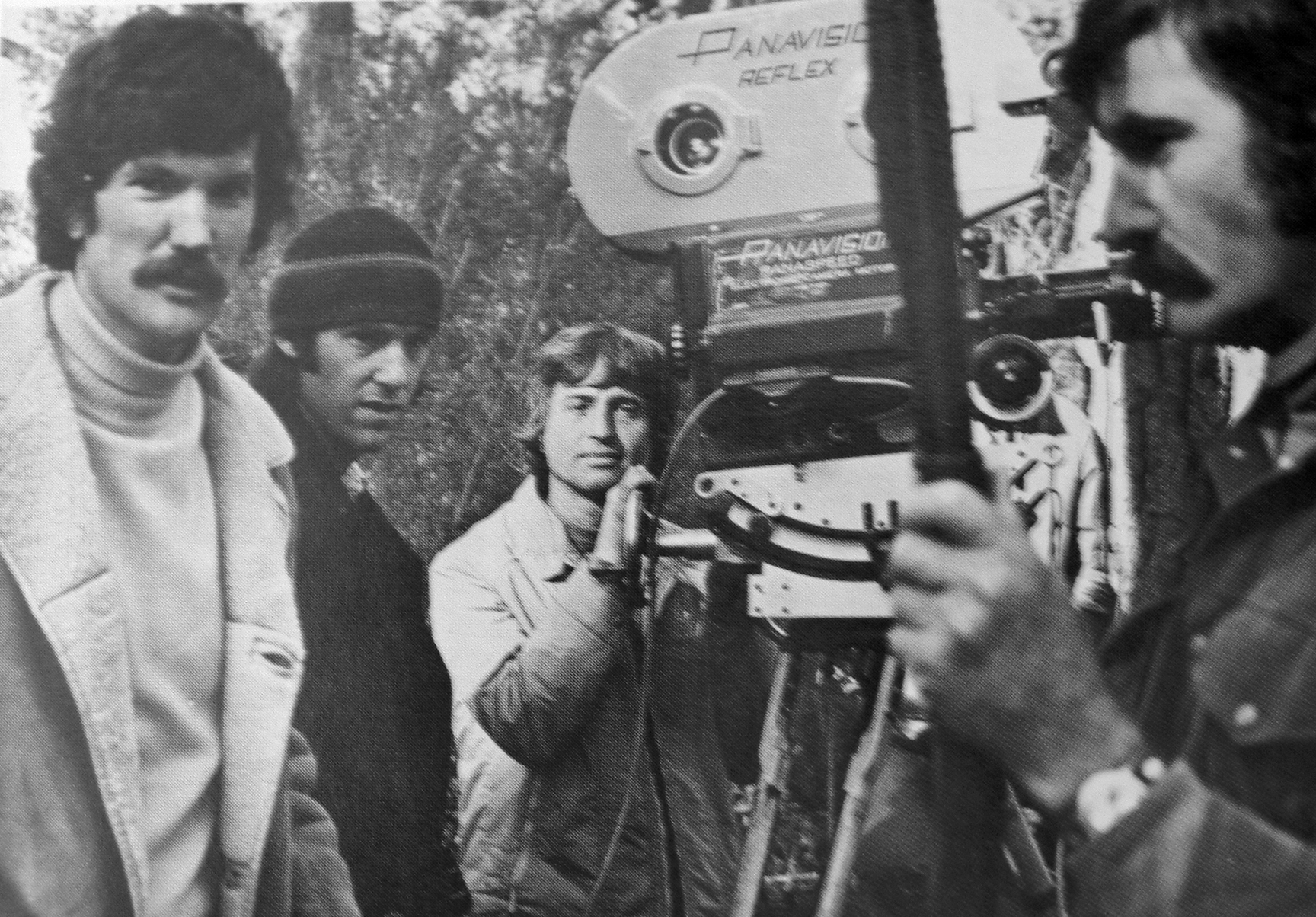

Kemper subsequently shot The Candidate, starring Robert Redford, in Northern California. Filmed almost entirely with two handheld cameras, the 1972 picture features a distinct music video/documentary feeling, though it was made long before MTV became the rage. The operators would "roam" while the sound man tried to keep pace. "Sometimes one camera got the other crew in the background," the cinematographer says. "We were roaming freely like news crews covering a campaign. We weren't signaling each other. We used what we needed and cut out the rest. We had used the same techniques on Husbands and most of the other pictures I'd shot up to that point. It was a different type of artistry with its own flow of movement. I was tired of the erratic handheld look, which is now having a renaissance, as though it was just discovered."

That same year, he worked on The Hospital, starring George C. Scott and directed by Arthur Hiller from a script by acclaimed writer Paddy Chayefsky. "He was a hands-on writer," says Kemper of Chayefsky. "He'd come on the set and ask what I was doing and why I was doing it. There was one six-page scene that we were going to shoot without any cuts, which would run for seven to eight minutes. We were rehearsing the scene in a metropolitan hospital in New York, and it was a monumental lighting job. We had to light the entire floor of this ward, which carried from the elevator to the nurses' station to the pharmacy it was a very large area for a small hospital. Scott was cast as a doctor. In this particular scene, he peeks into a room to talk to one of the patients, and then walks all the way back across the nurses' station, past the elevator and into another room where it is reported that someone has died in bed. Scott then continues with a very emotional scene in which he asks how this death could possibly happen in a hospital. Arthur Hiller loved to move the camera, and I did as well."

While Kemper was laying out the shot, Chayefsky arrived to offer his concern that the aggressive camera movement would detract from his dialogue. "I had to come up with a very good answer for him, or he would have gone to Arthur," Kemper reminisces. "I said, 'This doesn't take away from the focus of the dialogue. It goes with the dialogue. That's why the camera is moving.' He thought about that for a while and asked, 'Is that how the rest of the film is going to work?' I answered, 'Absolutely.' He was always involved. He wanted to know why or how the camera was helping his story, and that was a valid request."

According to Kemper, comedy is much more difficult to shoot than drama: “Timing is essential. The reactions of people in the cast, the scenery and environment are all part of every joke. Everyone in the cast has to be looking in the right place at the right time, and responding flawlessly.”

According to Kemper, comedy is much more difficult to shoot than drama. "Timing is essential," he observes. "The reactions of people in the cast, the scenery and environment are all part of every joke. Everyone in the cast has to be looking in the right place at the right time, and responding flawlessly. That requires rehearsals, but if you over-prepare, the humor loses its edge and it's not funny any more." He elaborates, "I'm not an actor, so I can't speak from their point of view, but I've seen the transition from the script to the spoken word many times. A good actress knows how to cry, and she has no problem repeating it time after time. But if a joke misfires and the audience doesn't think it's funny, you're on the road to disaster."

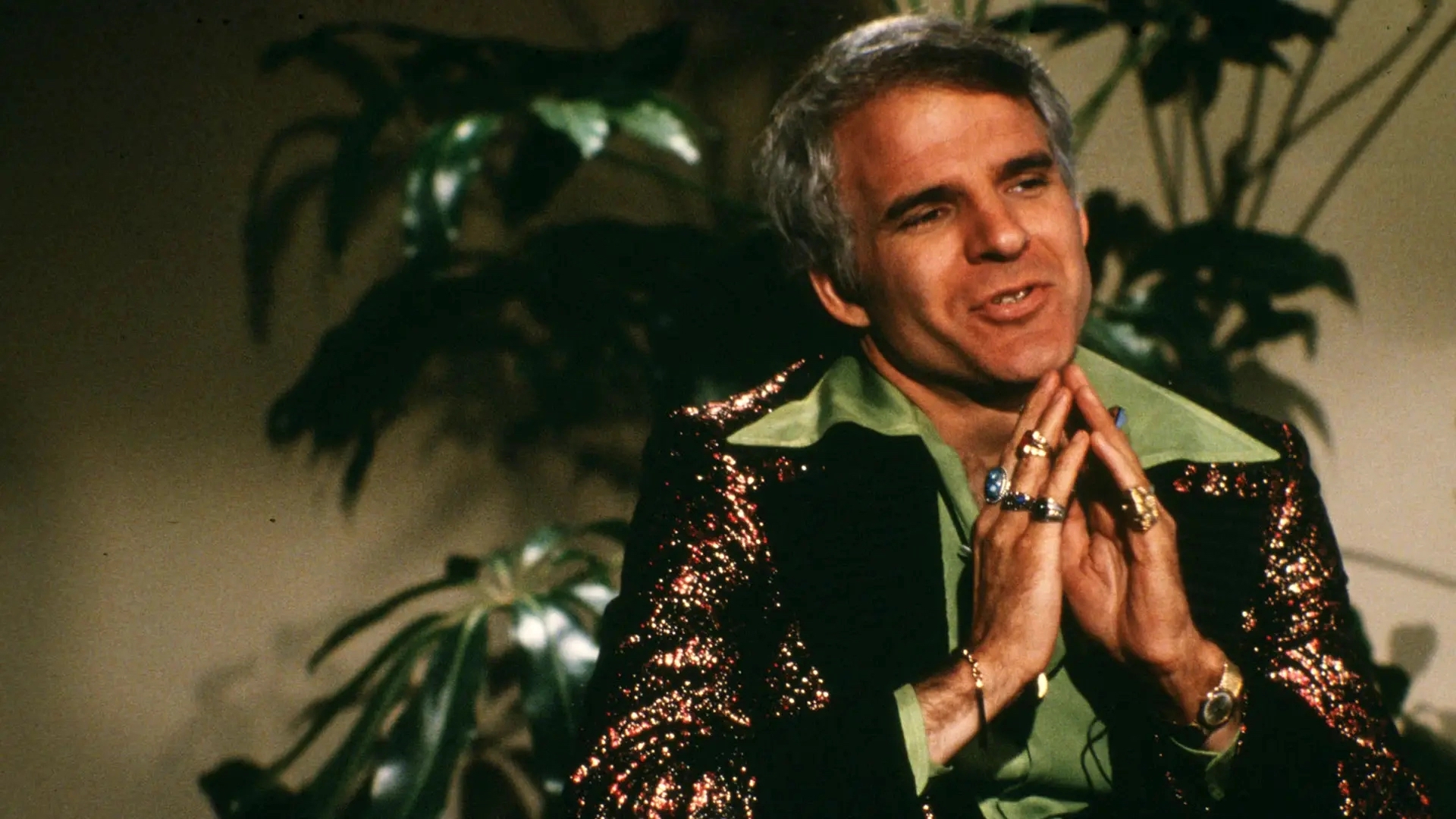

The Four Seasons is one of Kemper's favorite comedies because the film additionally featured a dramatic story that required a powerful presentation. He also admires The Jerk because actor Steve Martin made an implausible character believable.

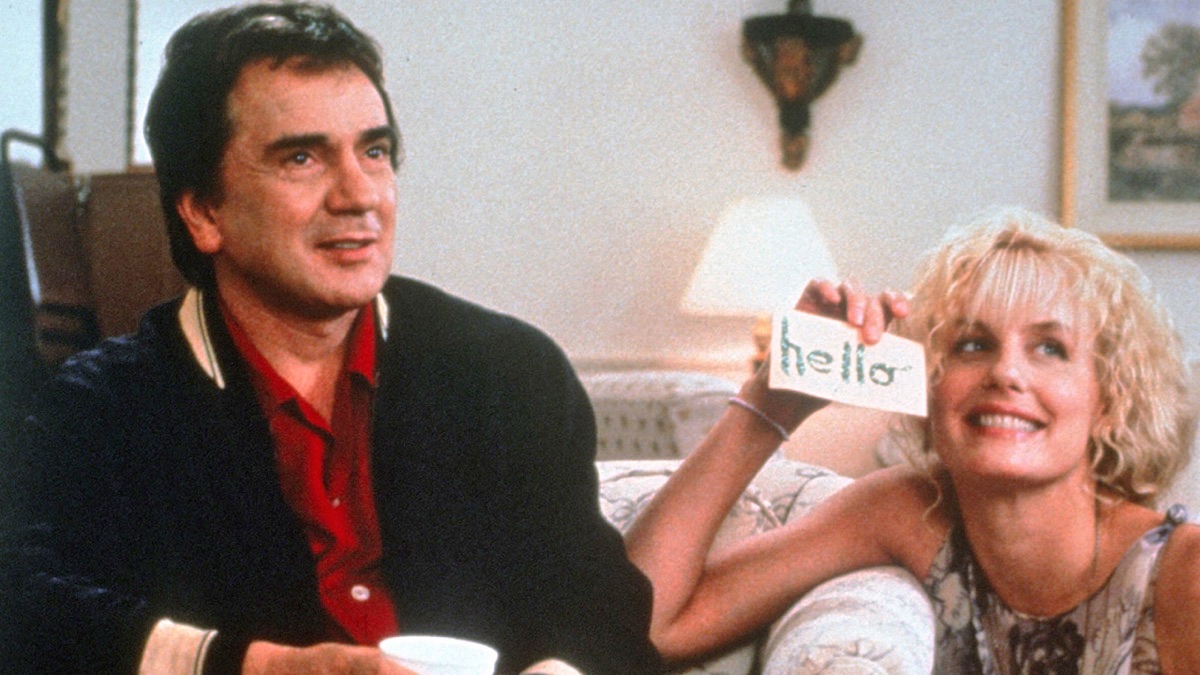

In 1990, Kemper got behind the camera for Crazy People (AC May '90) a romantic comedy set in a mental institution. Dudley Moore starred as a burned-out ad executive who is stashed in a sanitarium for some mental fine-tuning, and Daryl Hannah appears as one of the resident "crazies." Director Tony Bill initially considered using a documentary style for the picture, but Kemper nudged him in the direction of a less oppressive look with sharp, crystal-clear images virtually devoid of grain.

Kemper notes that Hannah and Moore seemed an unlikely romantic couple, but in the movie itself an electric current seems to crackle between their characters. "Daryl is irresistible on film," he says. "You can model her face with light. She takes three-quarter sidelight from above the lens beautifully from either side. But Tony didn't want her to look glamorous just beautiful and down-to-earth." Moore, on the other hand, looked best in flat light. On two-shots, Kemper lit Hannah first, and then flattened Moore's light with a separate handheld unit either alongside or below the lens, depending upon the angle. "The light on his face was always soft," the camera notes, "and he was never overexposed."

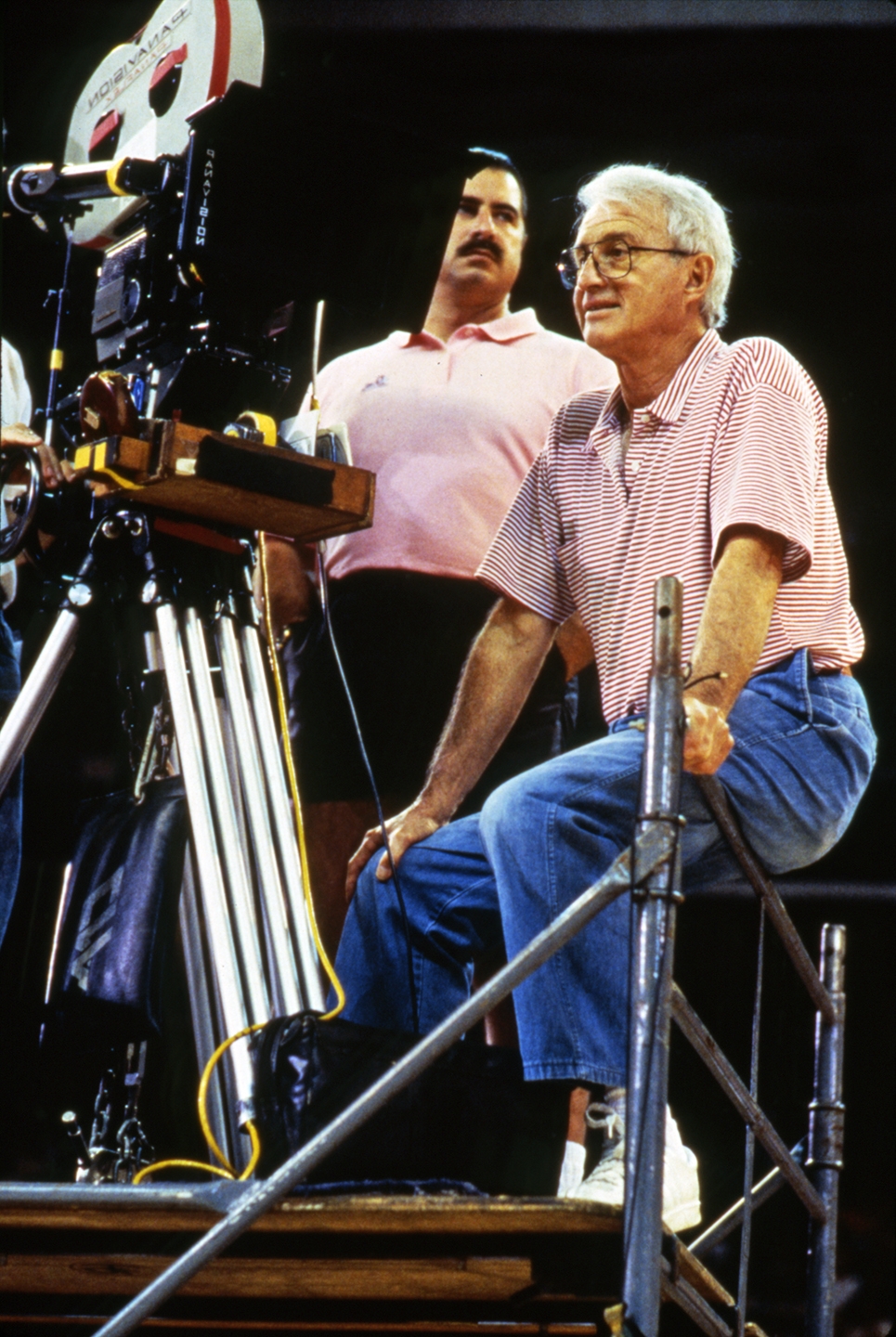

Kemper has an uncommon talent for creative problem solving. While shooting Eddie (AC June '96), a sports comedy about a female cabbie (Whoopi Goldberg) who becomes the coach of the New York Knicks, the cinematographer found that the Charlotte, North Carolina, location used as the team's home court was permanently lit with a combination of sodium- and mercury-vapor lamps designed and installed by Musco. "The lamps produced wonderful lighting for basketball games, but they generated tremendous green spikes on film," Kemper recalls. "I could almost see the green tint with my naked eye. I remember thinking that it would take forever to shoot tests and decide how to compensate with color-correction filters."

Of particular concern were the high tiers of stands in shadow areas, where the fans' faces would assume a greenish tint. Many filmmakers might find such a problem to be relatively small, but Kemper felt that even a hint of unreality could jar the audience into remembering they were watching a movie. The cameraman knew it was important for viewers to feel engaged in the sport's excitement.

During this period, Kemper met Mitch Bagdanowicz during a visit to Kodak Research Laboratories in Rochester, New York. Bagdanowicz had been experimenting with a spectral radiometer, an instrument designed to measure every color in the spectrum generated by direct and reflected light sources. Kemper invited him to bring the spectral radiometer to the Charlotte arena and measure each source of light for white, black and neutral skin tones in shadow areas and in pools of light.

Bagdanowicz ran the collected data through a computer that plotted a spectral curve which predicted where the green spikes would occur. Two days later far less time than other solutions to the problem would have taken he recommended to Kemper a combination of lamp and camera lens filters which would compensate for the green spikes. "Victor was at the peak of his career when he visited our research labs," Bagdanowicz recalls. "Most people in his position would have felt they had nothing more to learn, but he wanted to stay on the cutting edge. He was intensely curious about my experiments, and he understood how to apply it in a creative way."

Kemper made an indelible impression on the ASC when he served as president from 1991 through 1996, the longest consecutive tenure in the organization's 78-year history. In 1993, after the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) announced plans to replace NTSC with a new television system based on digital transmission, Kemper appointed an ad hoc committee to study the proposal's ramifications for both filmmakers and the public. The ASC subsequently became the creative community's first organization to give the FCC recommendations concerning this technology. "Our most important recommendation is that with digital transmission and widescreen TV, you can display all films the way they are meant to be seen, in their original aspect ratios," he emphasizes. "We wanted the FCC to ban panning-and-scanning. We haven't won, but we also haven't lost. The FCC left it up to the marketplace to decide. We aren't giving up. We have a moral responsibility to ourselves, to future generations of cinematographers and to the public."

When asked to name some favorites from his own body of work, Kemper confesses that, like most cinematographers, his first film, Husbands, remains his first love. But he adds that since he has shot so many films, a great many of them have special meaning. He singles out Magic, a 1979 thriller directed by Richard Attenborough and starring Ann Margaret and Anthony Hopkins. Kemper recalls that Attenborough gave him free reign to construct the lighting, setups and look of the film. "In Magic, we had four or five different looks because of the shifting emotions in the story. There was also a lot of night work, and that's always fun."

He also cites The Last Tycoon, a period film about Hollywood in the Thirties directed by Elia Kazan in 1976. "That picture was easy to make look good because of the work done by production designer Gene Callahan," says Kemper. But 20 years later, he still regrets not shooting the film in anamorphic: "It deserved to be seen in 'Scope, particularly the opening scenes with the earthquake and the flood that followed."

Dog Day Afternoon, directed by Sidney Lumet, invariably comes up when film aficionados discuss Kemper's work. Critic Pauline Kael characterized it as "one of the best 'New York' films ever made." Kemper muses, "I couldn't have shot it in Hollywood that way. It was counter to everything Hollywood believed in at that time. It wasn't glitzy. Sidney Lumet and the producers told me to make the film look as if it was happening right then in Brooklyn, New York. I just kept going over the script, watching the rehearsals and the sets being constructed. We made some interesting lighting changes during the bank robbery. That was conceived in my head, with no research. I suppose there might have been subliminal mimicking of something I saw before, but I doubt it."

They Might be Giants is also on Kemper's list of personal favorites. It's another "down-and-dirty New York film" made on a hope-and-a-prayer budget, shot entirely on practical locations. Pausing during this remembrance, Kemper maintains, "I still have some stories to tell. You never know what opportunities the next film will bring."

“Part of it is a craft you can learn; for instance, I learned about the elegance of reducing rather than adding light.”

When asked what makes a cinematographer great, Kemper advises, "Part of it is a craft you can learn; for instance, I learned about the elegance of reducing rather than adding light. But there is also something innate which whispers in your ear and tells you to move the camera a foot in a particular direction, or to shield a face partially in shadows. That talent may be there in your heart and soul, but you also have to learn the craft. You have to learn how to work with the director, cast and crew, and you have to be able to do it consistently."

Theorizing about why so few cinematographers achieve celebrity status, he observes, "Great cinematography has to be unobtrusive. It should never call attention to itself. You are there to help the director tell a story. Cinematographers aren't responsible for scripts or the tenor of stories, but if I accept a job I also accept responsibility for realizing what kind of influence it might have on the people who watch it. I made a conscious decision not to work on films which glamorize gratuitous violence or sex. I prefer pictures like Dog Day Afternoon or The Hospital, which have deep social meaning. I would also enjoy shooting a Western which I've never done, or an epic story where the audience can really observe the environment."

Looking back on his long career, Kemper says that he wouldn't do anything differently: "If I had another life to live, I would probably do the same things over again."

Subsequent to the writing of this profile, AC recorded a podcast with the cinematographer regarding his work in the memorable 1973 crime drama The Friends of Eddy Coyle, in discussion with Richard Crudo, ASC. Listen here.