President’s Desk: Film Is Dead!

The argument can be made that we might eventually outrun ourselves with digital technology, and that we sometimes seem to bet hopelessly on a dead horse, so to speak.

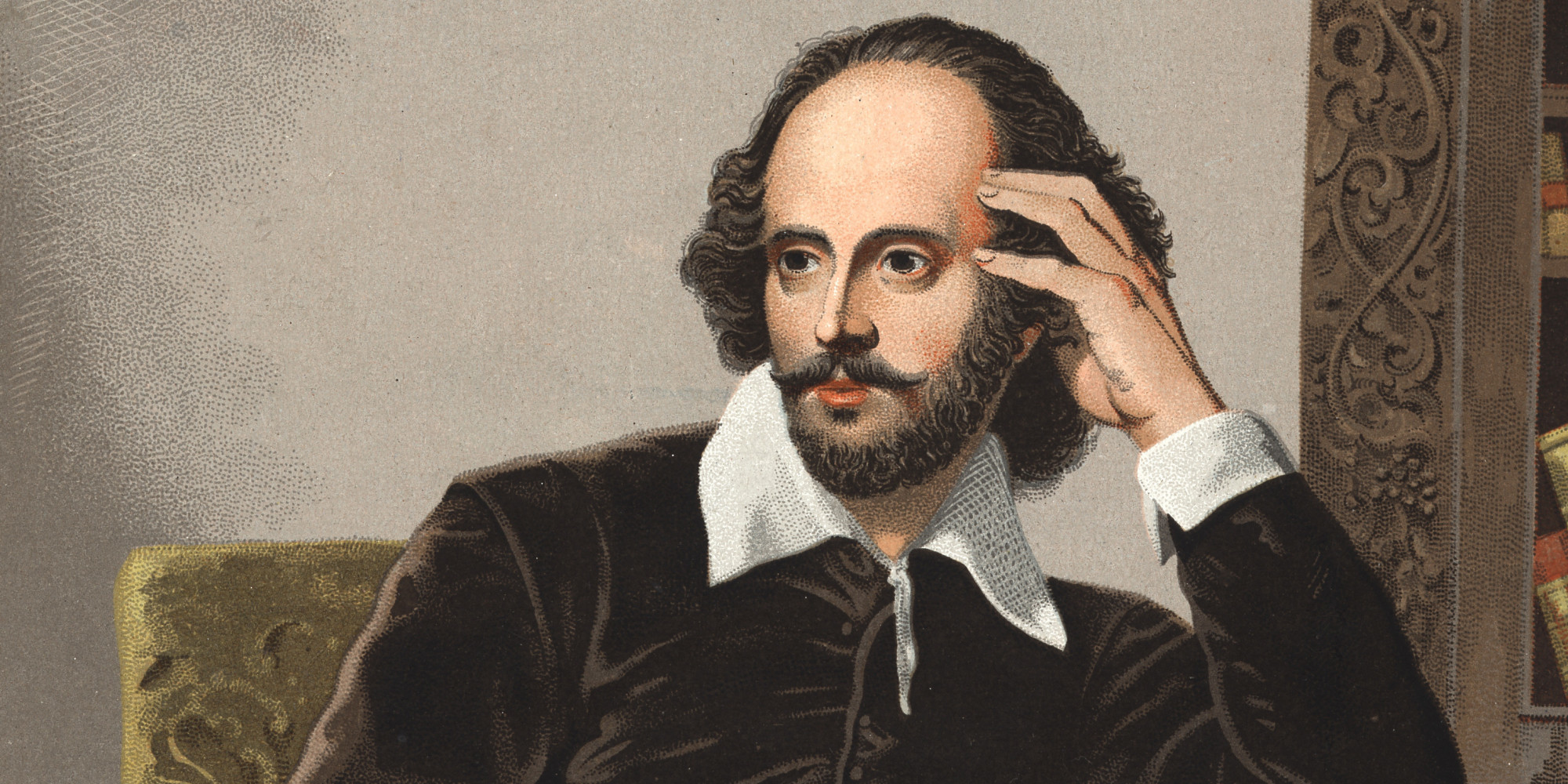

And so is William Shakespeare, who’s frequently cited as the greatest writer in the history of the English language and, arguably, the pre-eminent dramatist in the history of the world. His body of work includes nearly 40 plays and more than 150 sonnets. His works — among them the tragedies of Hamlet, Othello, King Lear and Macbeth — have been continually adapted, rediscovered and staged from fresh perspectives. Even today, his plays are performed more than those of any other playwright.

As Nelson Mandela once said, “Shakespeare always seems to have something to say to us.” Such a heartfelt and widespread response is perhaps Shakespeare’s most remarkable achievement, his unique gift to our culture, language and imagination.

With the Bard in mind, perhaps the “death of film” is not so evident. It was about eight years ago now that digital imaging systematically washed over anything that had previously been shot on film. In a relatively short amount of time, it took over television and, largely, feature production. The technology successfully convinced many that the digital image was not just newer, but that it was cleaner and more resolute than the film image — and that it would continue to follow Moore’s law.

Based on the observations of Intel co-founder Gordon E. Moore — and open to some interpretation — Moore’s law roughly states that the processing power of a microprocessor doubles every 18 or 24 months. And, yes, digital imaging has followed a similar trajectory, as we have rapidly gone from HD to 2K, to 4K, to 6K and to 8K.

But what has been constant throughout these last eight years is our ongoing reference to the look of film. At first we compared the images side by side, debated their dynamic range, argued about resolution, and obsessed over color reproduction. Every concern was met with the same answer: “Wait six months and it will be better.” And, indeed, it did get better. The colors grew more vibrant and the contrast richer; the definition became incredible and the dynamic range expanded. Even now, it will become better still!

But there has also grown something of an underground revolution, spurred by cinematographers worldwide. As new lenses boasting distortionless optics were developed to serve as true 4K instruments capable of incredible transmission and ultra-sharp rendering — effects that, for some, evoke the words “sterile,” “unreal” and “emotionless” — the revolutionaries started to pull out the classic lenses, the vintage filters and stockings. Suddenly, the deconstruction of the digital image was in full swing.

Meanwhile, film-processing labs everywhere were either closing or morphing into digital-workflow emporiums. But the occasional film lab managed to survive, and to provide the revolutionaries with the ability — against all odds — to shoot and process film.

This is not so incomprehensible, as cinematographers will always talk with each other about film. It’s not so much nostalgia or even comparing technical parallels; it’s simply the “look.” We argue about how light and dark are recorded; how bleach bypass has become a thing of the past, with its deep, vibrant blacks impossible to reproduce in digital; and the way film grain affected the experience of color and texture. These are all things we’ve tried hard to emulate in digital, but in the end we haven’t really achieved.

The number of movies shot on film has doubled over the last year. Although it represents only maybe 5 percent of all features, it is remarkable that it has come back at all. Labs are opening again instead of closing, and there is a tremendous resurgence in interest among a young group of filmmakers who are deeply curious about film — about the craftsmanship required to work with it and, foremost, about its feeling.

During awards season, the field of cinematography nominees can still be disproportionately dominated by films shot on film. And as for Moore’s law, it’s been predicted that its own life expectancy will, ironically, end around the year 2020.

I think the argument can be made that we might eventually outrun ourselves with digital technology, and that we sometimes seem to bet hopelessly on a dead horse, so to speak. A horse just as dead as William Shakespeare, whom I will quote here at the end:

“Thou know’st ‘tis common.

All that lives must die,

Passing through nature to eternity.”

Kees van Oostrum

ASC President