President’s Desk: Optical Unconsciousness

When we talk about lenses for cinematography, most cinematographers are knowledgeable and opinionated.

When we talk about lenses for cinematography, most cinematographers are knowledgeable and opinionated. In the years since Ernst Abbe partnered with Carl Zeiss in Germany and started to produce photographic lenses as we know them today, many others have followed with their own optical designs, intending to reproduce the image truthfully, as the human eye sees it. But concurrently with the technological advances of the 20th century came the creative notion of honoring the artistic experience — how we feel about an image. With the birth of digital cinematography, that feeling has come to the forefront, as digital sensors arguably reproduce a sharper, more defined, but less romantic image.

We have therefore fallen back on optics from the past, so-called “vintage lenses,” and have recently gone to great lengths to re-create those older looks through various and intricate lens-tuning procedures. We have reached a point that Bradford Young, ASC poetically describes as “finding a relationship with a lens, and the lens finding its relationship with us.”

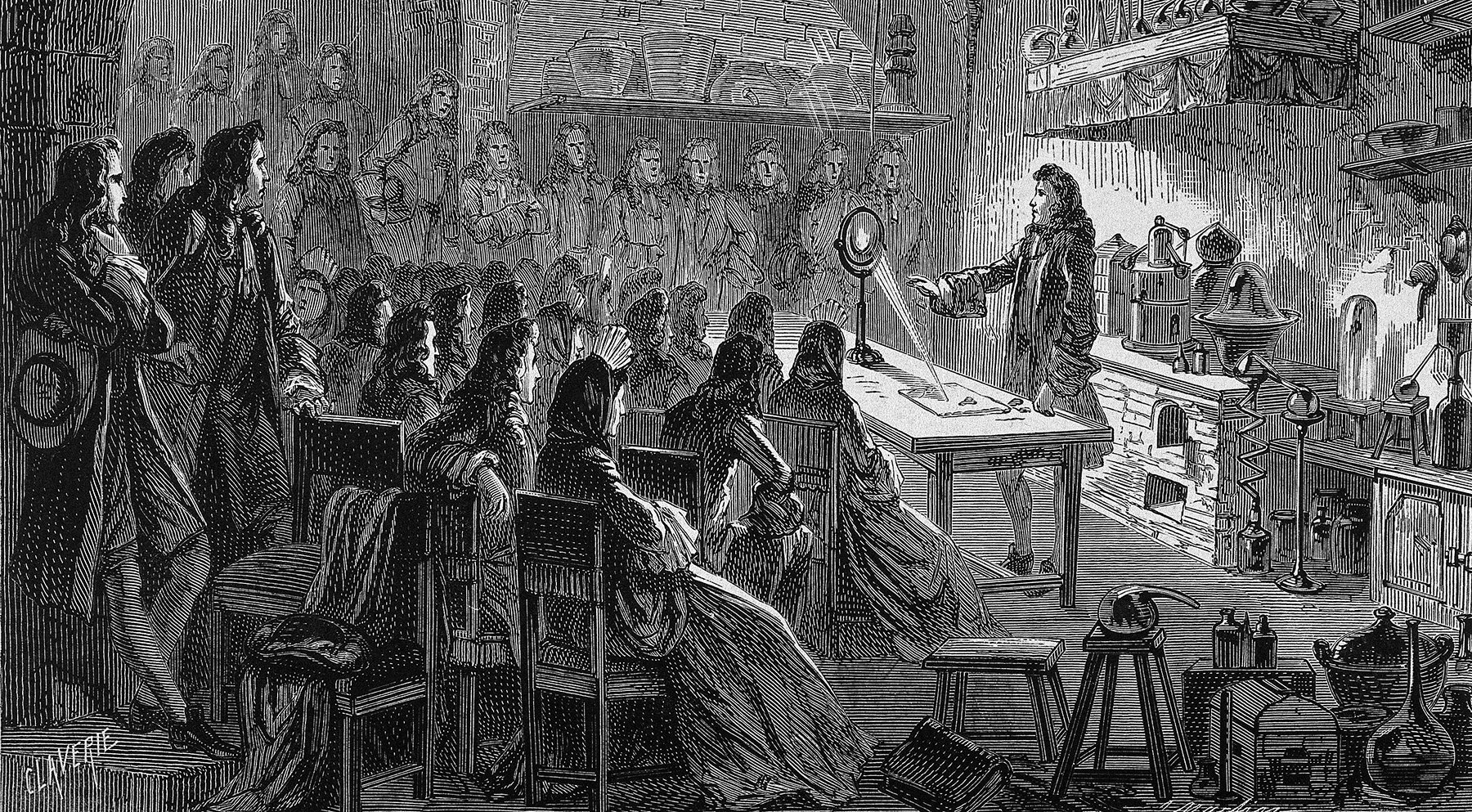

When ancient scientists began experimenting in an attempt to decipher the secrets of life, the universe and the world we live in, one specific question came to the fore: What is light, how does it travel, and how can we take advantage of its properties?

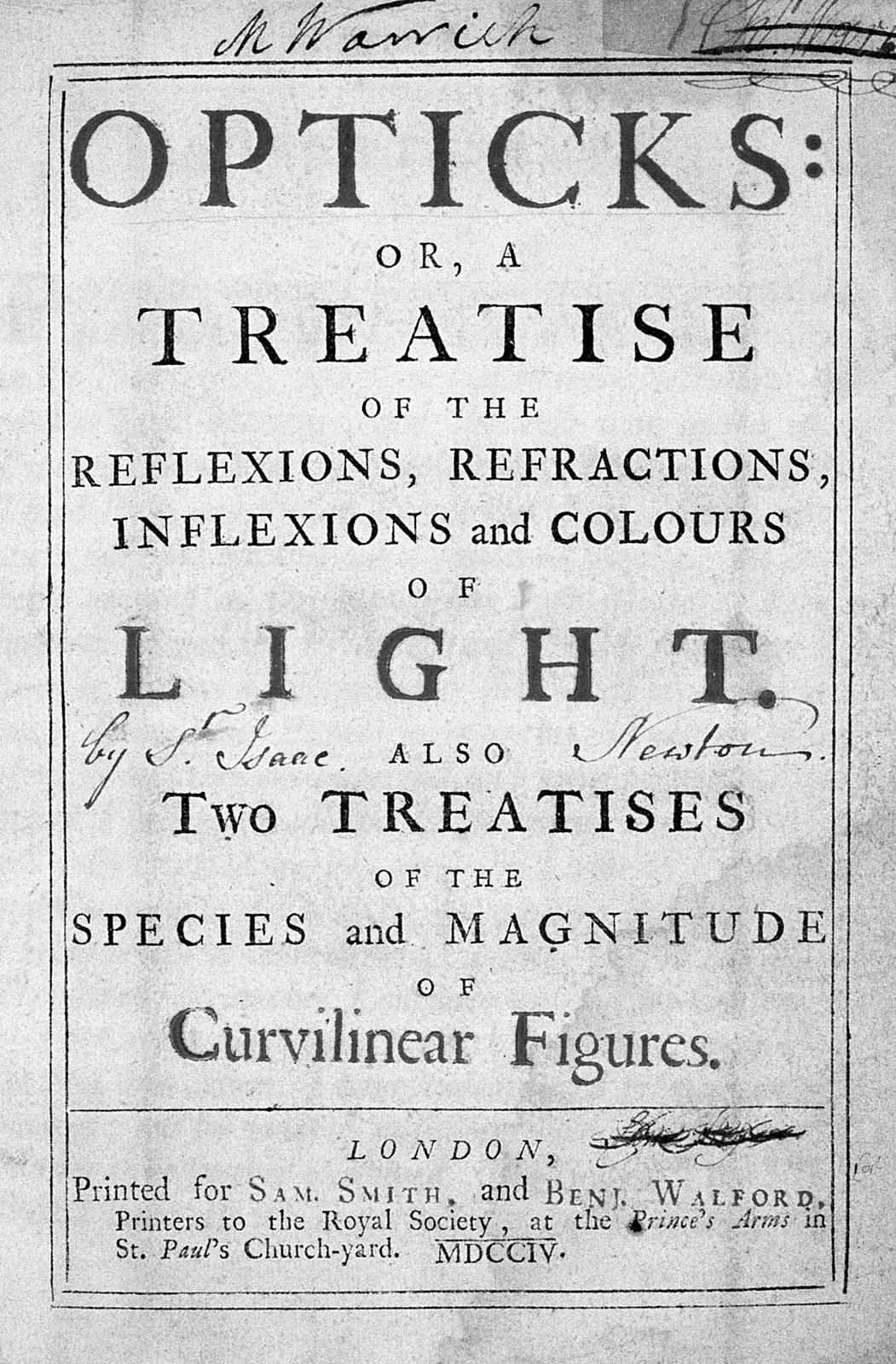

Answers to that question started coming into focus around 700 B.C., in ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia, with the creation of the first crude lenses, which were fashioned by polishing crystals — often quartz — in an attempt to replicate the optical characteristics noticed in water. These first steps fueled the imagination and resolve of the Greek and Roman mathematicians, physicists and inventors whose experiments would form the foundation of classical optics. More technical optical discoveries continued in the Western world with the work of René Descartes, Robert Hooke, Christiaan Huygens and Isaac Newton; the latter’s book Opticks was accepted as the highest achievement in light research at the time of its publishing in 1704.

It was then not until the late 19th century that optical theory and practice advanced significantly. Abbe helped to found the Zeiss plant in Jena, where he set Otto Schott to work examining the influence of different elements on the optical characteristics of glasses. The use of boron and barium compounds led to several categories of optical glass; Schott would go on to found his own company, which produced such special glasses.

In the midst of the Gilded Age and the rapid expansion of industrialization, lens design progressed with previously unparalleled performance. Yet as Richard Prouty notes in an essay concerning the 1930s writings of Walter Benjamin — the German philosopher, cultural critic and essayist — “at some point in history [...] we lost the ability to tell the difference between the image and the world, between the real and the artificial.” Benjamin was highly influenced by surrealism, and he admired the work of the early 20th-century photographer Eugène Atget, whose misty and soft character photographs of a deserted Paris were like the scenes of a crime.

Benjamin's idea that “improved technology can expand our sense perception and make the unconscious visible,” as Prouty summarizes, perhaps inspired Virginia Woolf's invocation of the term “Optical Unconsciousness.” In Three Guineas, Woolf writes, "Let us then by way of a very elementary beginning lay before you a photograph, a crudely colored photograph of your world as it appears to us who see it from the threshold of the private house; through the veil that St. Paul still lays upon our eyes; from the bridge which connects the private house with the world of public life."

With this essay, Woolf, an avid photographer, considers reality in the context of appearances that are shrouded by veils. She printed photographs in her own darkroom, and in letters to friends and relatives she often spoke of writing as “painting portraits.” Woolf narrates the inner out into the open for others to experience, and she reached beyond the purely photographic, employing an imagination that is indicative of the theory of “Optical Unconsciousness.”

It’s a theory that we cinematographers, too, can be inspired by, and that can provide insights concerning the character of lenses and how we judge the unclassified look of “vintage glass.” We need to remove ourselves from pure technicalities and hone our sensibilities to an instinctual consciousness — a way for us to think, feel and be inspired to combine technological innovation with the mysterious veil of surrealism.

Kees van Oostrum

ASC President