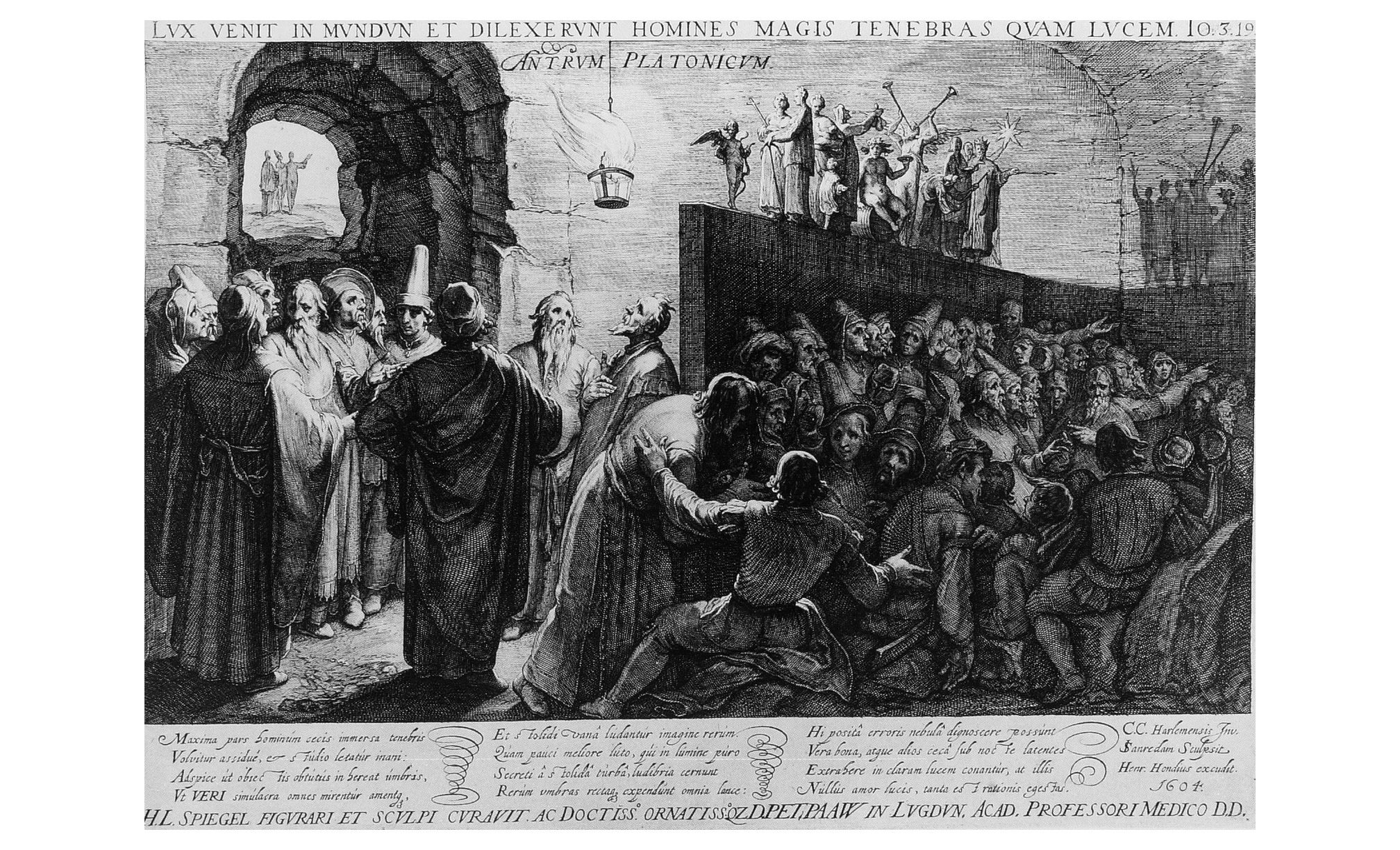

President’s Desk: Plato’s Cave

“The phenomena of light and dark long ago inspired Plato, as he expressed in his allegory of the cave...”

I was daydreaming recently, watching the late afternoon sun dramatically scratch the walls of my room, creating deep shadows and a stark contrast between light and dark. It reminded me of the proverb: There can be no shadows without light. And it reminded me that, for cinematographers, light is a strong tool with which to express ourselves, reaching far above and beyond the technology of a camera and the sharpness or tonality of a lens. In some ways, it is even more powerful than a moving shot or the strength of a frame.

The phenomena of light and dark long ago inspired Plato, as he expressed in his allegory of the cave.

The allegory tells of a group of prisoners who have lived their entire lives chained in a cave; they face a blank wall, on which they see shadows projected by objects that pass in front of a fire behind them. These shadows constitute their reality. One day, however, one of the prisoners is freed. Seeing the firelight directly, his eyes are hurt, and he turns back to the “comfort” of the shadows on the wall. Another freed prisoner, however, manages to push on through the cave, past the fire and outside, where he sees the sun. Though at first the sun blinds him, once his eyes adjust, he sees that his reality is not at all what he had thought it was.

It could be argued that with this story, Plato envisioned the “movieplex” long before it came to be, but what’s truly important for us to recognize is the power of light in Plato’s allegory. The fire represents imprisonment; the sun, freedom. He used light and shadow — even the color of light — for dramatic visual effect as he told a story from an instinctual point of view.

Of course, one of the most outspoken cinematographers when it comes to the topic of light and color is Vittorio Storaro, ASC, AIC, who has noted: “To me, making a film is like resolving conflicts between light and dark, cold and warmth, blue and orange, or other contrasting colors. There should be a sense of energy or change of movement. A sense that time is going on — light becomes night, which reverts to morning. Life becomes death. Making a film is like documenting a journey and using light in the style that best suits that particular picture … the concept behind it.”

In explaining his style for The Last Emperor, Storaro describes the quality of natural light as it relates to the emperor’s spiritual awakening:

“The Sun is our main source of energy. It gives us the full range of the spectrum … all the colors. I asked myself, ‘How could we represent his life through the use of colors?’ If they kept the emperor away from knowledge, he had to be shielded from light. At the beginning of the picture, he never sees his own shadow. The people around him kept the young emperor in the ‘penumbra’ of partial shadows. As he begins learning from a tutor what is happening outside the walls, the sun touches his face, and he sees his own shadow for the first time. The more he learned, the more light I poured on him, and the darker his shadow became. As he finds more balance in his life, the audience begins to see more of a harmony between light and shadows.”

Storaro directly refers to Plato’s philosophy, and proves the point that the strongest storytelling ability we possess as cinematographers is our use of light. Light, after all, is something that makes vision possible. And light is what defines the dark — even for the prisoner who, momentarily confronted with freedom, quickly returned to his shackles and the fire-lit world of shadows flickering across the “screen” in Plato’s cave.

Kees van Oostrum

ASC President