President’s Desk: The Black Cat and the White Cat

When I was a cinematography student, my classmates and I enjoyed learning from a rather eccentric teacher. He was supposed to illuminate the technical aspects of cinematography: f-stops, depth of field, basic optical principles, etc.

When I was a cinematography student, my classmates and I enjoyed learning from a rather eccentric teacher. He was supposed to illuminate the technical aspects of cinematography: f-stops, depth of field, basic optical principles, etc. Rarely, though, did he ever get around to that. Instead, our afternoons were usually occupied with his obscure cinematic experiments or his short films in which he appeared as a blind man wandering through the world.

I was recently reminded of one of his technical experiments. On a sunny afternoon, he arrived at the school with an animal carrier that contained two cats, one black and one white. These were his pets Noir and Blanche, their names meaning “black” and “white,” respectively, in French. The question for the afternoon was how to deal with them in shadow and sun while retaining detail in their fur. And the challenge, of course, was that we were shooting on black-and-white reversal film, with an effective latitude of maybe four stops.

The photographic solution was to put Noir in the sun and Blanche in shadow — which might sound easy but was no simple feat to realize. Who has ever met a cat that takes orders? But after a few sardines and a handful of scratches, we accomplished the task and excitedly rolled some film. When we screened the footage the next day, it was a revelation: Both Blanche and Noir showed up with nice detail in their fur.

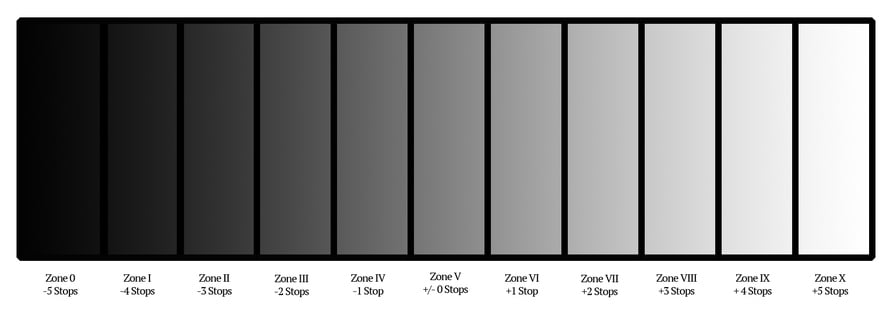

This was my introduction to Ansel Adams’ “zone system,” a particular method of determining what you want to see reproduced in a photographic image in order to create an impression and tell a story — almost like a painter using a brush. The zone system allows us to relate a subject’s various luminances with gray values ranging from black to white that will be represented in the final image. This forms the basis of the visualization process, whether the photographic representation is intended to be literal or a departure from reality.

What brought these memories back to me was a recent encounter with a digital-capture system that boasts a 15-stop latitude and a great variety of postproduction controls for manipulating density and color in selected areas of the frame, taking advantage of that extended latitude to retain maximum detail from the shadows through the highlights. With this system, Noir and Blanche could be photographed peacefully eating their tuna in sun and shadow — and then made to look like identical gray cats!

In today’s world of greatly extended latitude and super-sensitive capturing systems, you can, in most cases, shoot in available light. You can walk out into the world, photograph it, and come home with an image. But the question remains whether that image fully expresses or uses to a great extent your abilities as a cinematographer.

How we light a scene is one of the most important choices we make in the expression of our artistry. It deals with density, color contrast, and the photographic reproduction of black and white. I am fully aware that we can arrive at these choices in post, but there is much to be said for making these decisions in the moment of creative inspiration, which largely exists on the set.

In the end, I don’t think we want to visually portray our world in a blend of gray where everything is visible. I don’t think Ansel Adams went about his craft that way. And I don’t think Noir and Blanche would rest in peace knowing they might possibly both be gray today.

Kees van Oostrum

ASC President