Carne y Arena part 2 - Notes on VR Cinema Design

Notes on aesthetic and technical design of Virtual Reality cinema brought up by Carne y Arena, by Alejandro Iñarritu with Emmanuel Lubezki, ASC, AMC

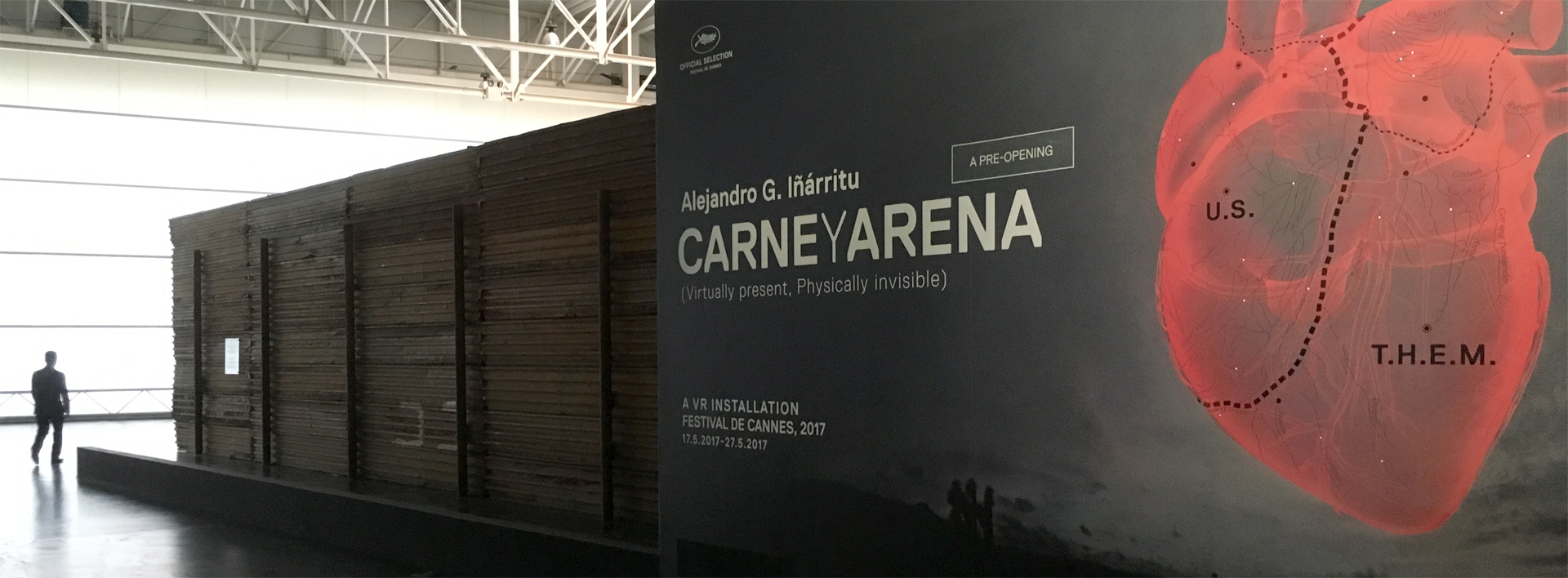

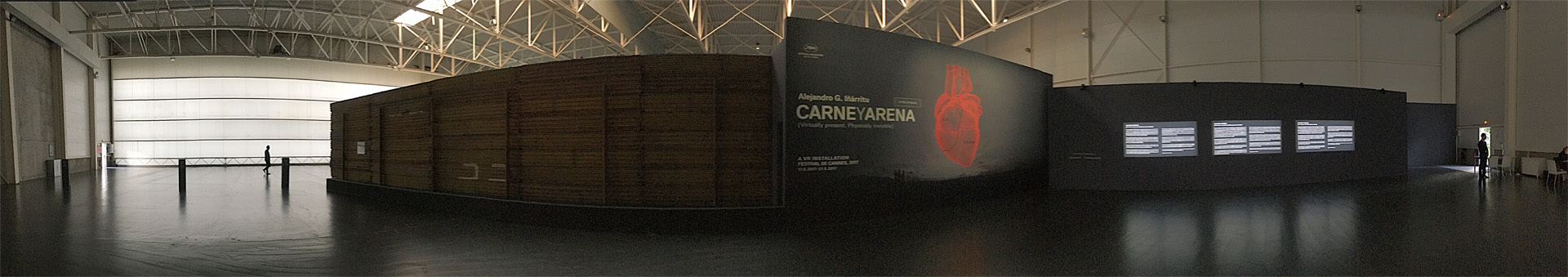

This post offers notes on the aesthetic and technical design of Virtual Reality Cinema brought up by seeing Carne y Arena, the VR masterpiece created by Alejandro G. Iñárritu with Emmanuel Lubezki, ASC, AMC, with the support of Legendary Entertainment and the Fondazione Prada.

If you haven't read part one which describes my experience of this amazing art installation, you may want to do so before reading on.

+++

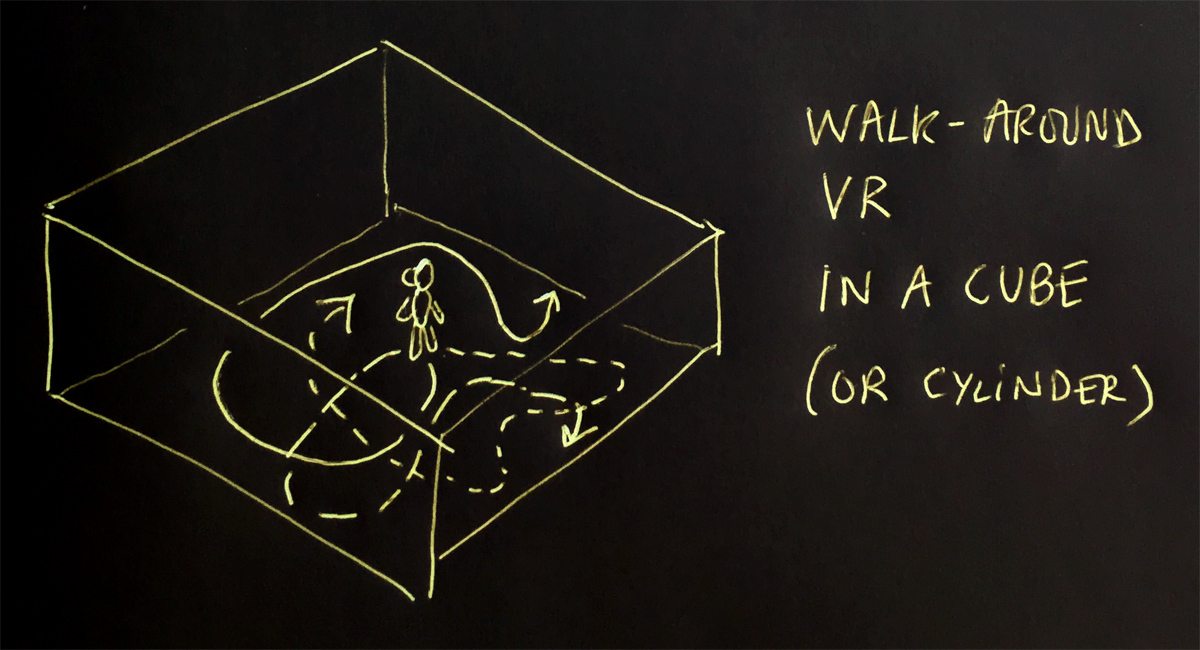

To discuss VR Cinema design, I start by distinguishing between two types of VR:

-- Head-turn VR

-- Walk-around VR

+++

Head-Turn VR

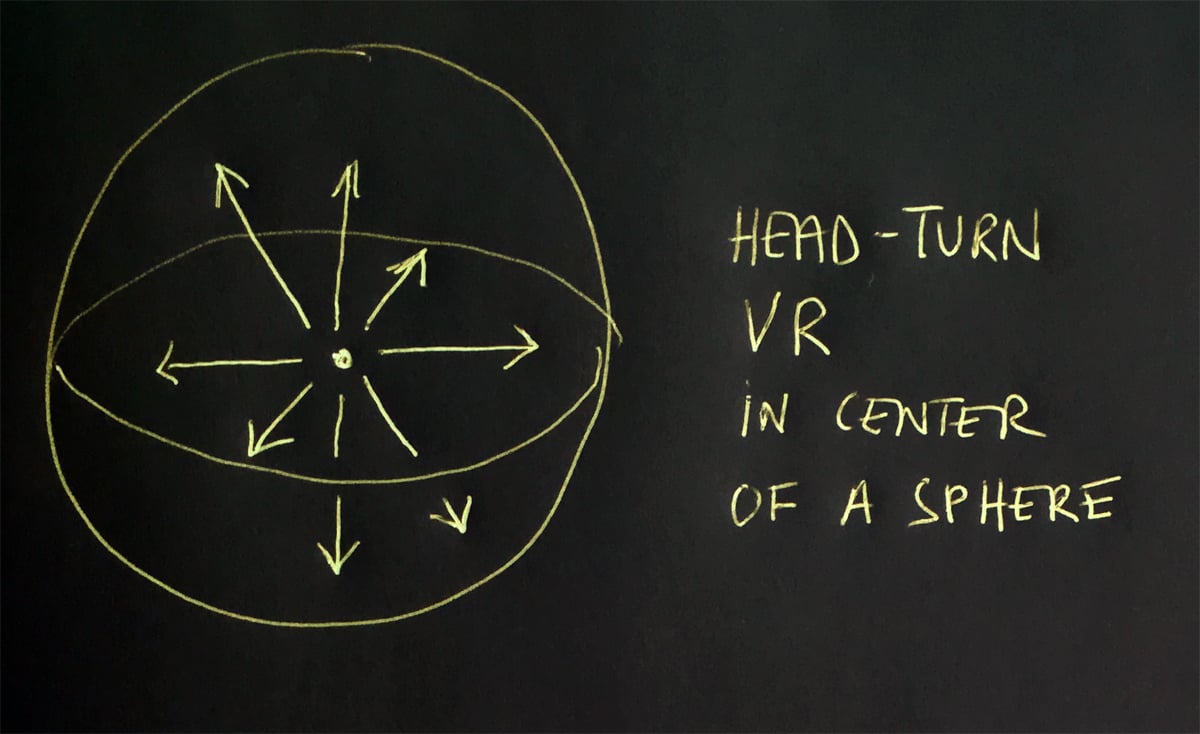

The most common type of Virtual Reality sticks you in the center of a virtual sphere (or some portion of a sphere). You can move your head, but your body position is fixed. This kind of VR movie is sometimes viewed on a rotating stool.

The images in Head-Turn VR can be shot with a VR camera system, or computer-generated, or both. VR camera systems can be either 2D or stereo 3D, and typically involve multiple cameras whose multiple images are "stitched" together in post. Creating good Stereo 3D images is a difficult art, creating good Stereo VR even more so.

Note that the VR image can be an entire sphere, a hemisphere, or other variations. Google has recently introduced VR180, with imagery limited to a hemisphere in front of the viewer.

Head-turn VR can also involve images that move through space, like a jet plane ride with optional speed and direction controls. But you are still sitting on that stool.

To date, I have seen two pieces that I consider masterpieces of Head-Turn VR:

-- Maasai, an episode of Nomads by VR masters Felix Lajeunesse and Paul Raphael with sound by Headspace Studio. The extraordinary naturalism of Felix and Paul's stereo 3D and audio technology succeeds in placing you in front of Maasai tribesmen, and most importantly, of really conveying their presence.

-- Notes on Blindness: Into Darkness conceived by Arnaud Colinart, Amaury La Burthe, Peter Middleton & James Spinney with cinematography by Gerry Floyd, places you in darkness and evokes blindness by visualizing the sounds that surround you with beautifully poetic processed imagery.

For me, the key advantage of using cameras in Head-Turn VR is that they can record natural images that transmit the presence of someone's face and eyes. Our ability to see and recognize faces is part of our humanity. It is also an essential part of most cinema.

+++

Walk-Around VR

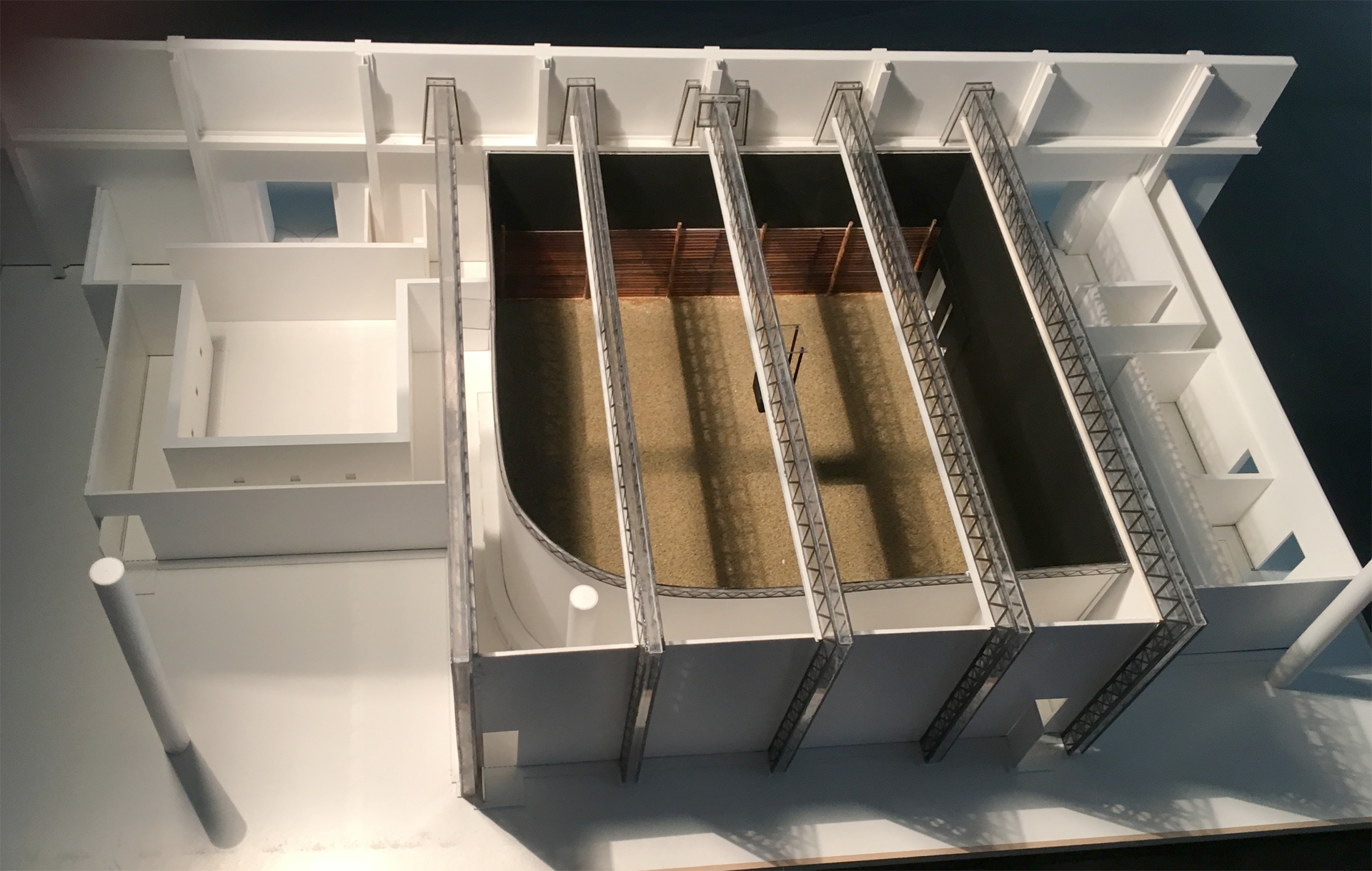

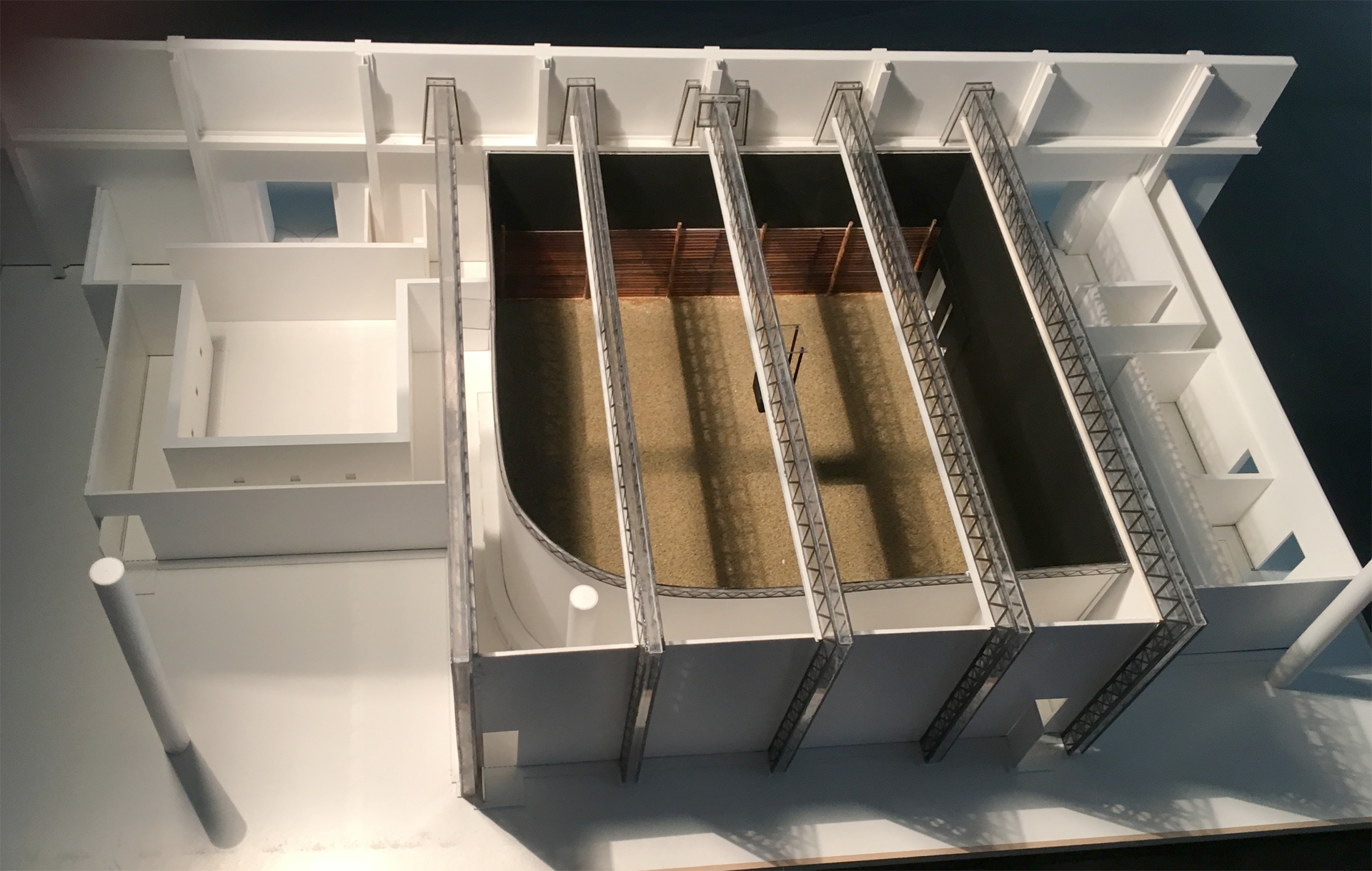

Carne y Arena is most probably the biggest Walk-Around VR piece to date, and takes place in an area as big as a tennis court. As described in part 1, you are free to walk around, and stand or sit or kneel. When you reach the edge of the VR area, there is a gentle tug from a technician to pull you back in to the defined space.

With present technology, it's just about impossible to use a camera system to shoot VR for a piece where the audience can move around freely. This is because you would have to shoot the action and the background from all the possible audience vantage points, to record all the possible audience paths through the virtual space for the duration of the VR movie.

At present, the way to create a Walk-Around VR piece is to use computer generated imagery, and then render virtual characters and backgrounds in real time based on the viewer's current position. There are few Walk-Around VR movies out there. But I have seen one extraordinary Walk-Around application: Google's Tilt Brush, which I experienced with an HTC Vive system.

The Vive system allows you to set up a small motion tracking system in your living room. With Tilt Brush you move a hand controller to create 3-dimensional paintings that you view with a stereo 3D headset. The real-time data involved is not huge, as it's just an intertwining series of colored brush strokes, but the interactive experience is truly exhilarating. Tilt Brush demonstrates the intriguing capability of enabling the viewer to transform the virtual world they move around in.

+++

Performance Capture

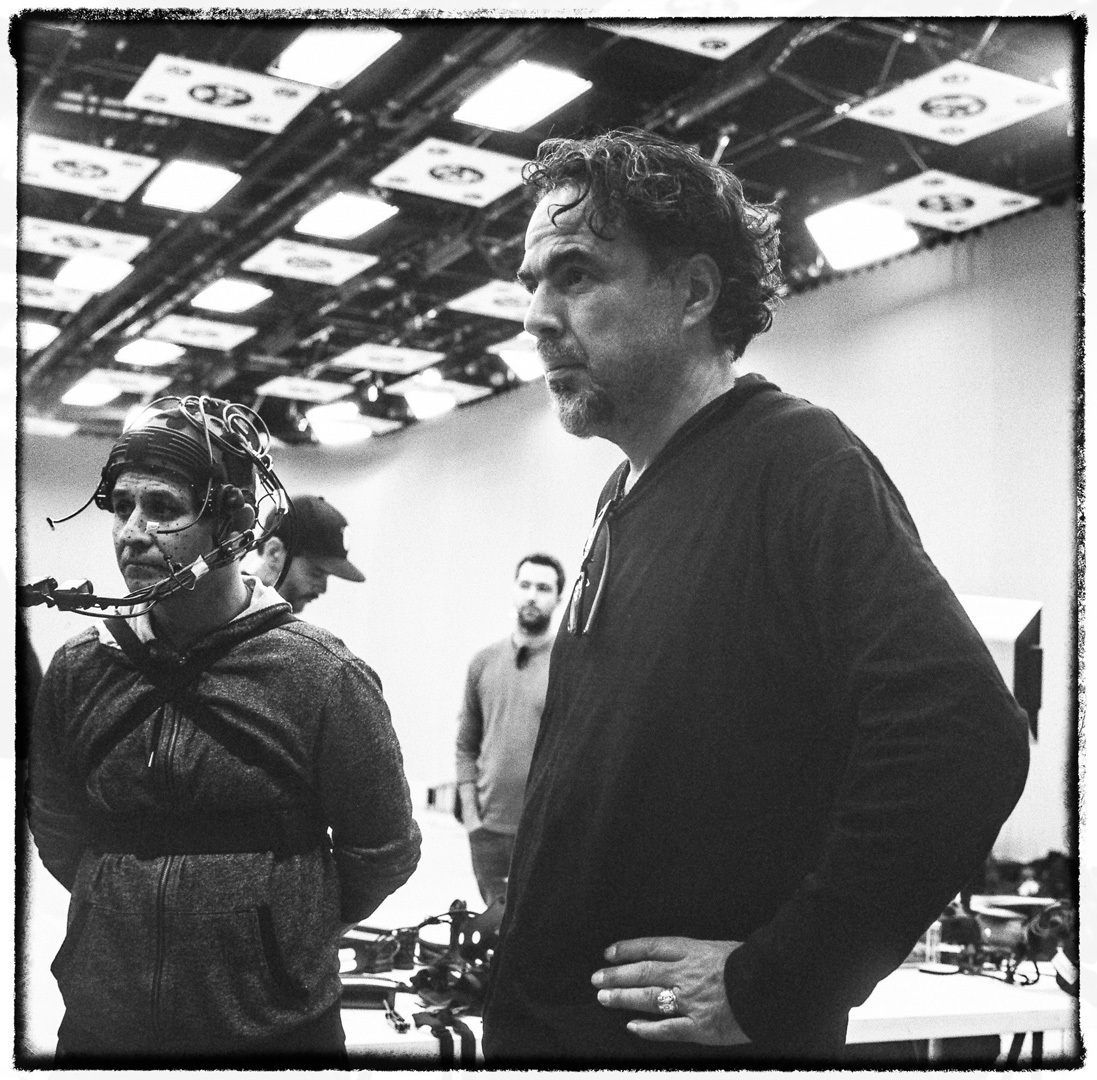

Walk-Around VR gets very complex if you want to create a realistic virtual world like the one in Carne y Arena. Emmanuel Lubezki and Alejandro G. Iñárritu have a shared penchant for naturalism, an aesthetic that guided their award-winning collaborations on Birdman and The Revenant.

To create lifelike virtual characters, you can shoot actors with performance capture. This technique was notably pioneered by Avatar and involves recording the actors with a camera/computer system that can digitize their movements, gestures and expression by recording reference points on their bodies and faces.

Depending on the complexity of the VR world, real-time rendering of virtual characters and backgrounds can require a lot of computer power, because the slightest delay between your movements and the VR world around you will break the spell. In Carne y Arena this rendering works seamlessly, and the result is an extraordinary verisimilitude, an amazing experience of moving through a virtual world.

+++

Uncanny Valley

Performance capture does a great job of conveying the physical gait and gestures of an actor. To date, the technique has been especially successful at creating convincing aliens and animals, like blue-skinned avatars, Golum or the memorable bear in The Revenant.

At present, it's still a challenge to create lifelike human faces and eyes, although that may change soon. Computer animators have noticed that, as the accuracy of verisimilitude increases, virtual beings become eerily inhuman, a phenomenon called "the uncanny valley" -- so that very accurate faces can be perceived as more lifeless than cartoons. This is the danger of seeking naturalism in Walk-Around VR: the virtual characters can seem like animation caricatures. No one is more aware of the Uncanny Valley than Emmanuel Lubezki, who worked tirelessly with Alfonso Cuarón to avoid it, by adding real human faces to the virtual bodies in Gravity.

+++

Presence Versus Experience

Comparing Head-Turn VR with Walk-Around VR leads me to compare presence versus experience:

-- because you can use cameras to record real people in Head-Turn VR, you can transmit the presence of a person's face and eyes.

-- because you can create a virtual world in Walk-Around VR, whose appearance changes with your every move, you can create a realistic experience for the audience.

Another way to put it is that the audience is more present in Walk-Around VR, while the characters are more present in Head-Turn VR.

There are thresholds of presence, with different resolutions. A moving silhouette from afar might be perceived as a human or an animal. You can recognize a familiar person by their gait -- the way they walk -- even in silhouette. Recognizing the humanity of a person's face offers the most presence, but it is difficult to accomplish without photographic cameras.

In Carne y Arena, the artists had the salutary idea of complementing the virtual characters in VR with the faces of the real people who inspired this powerful piece, in a row of video monitors. So, after the formidable experience of the virtual world, the audience's parting experience is the presence of real immigrants.

In a way, the shoes, clothes and personal effects of immigrants in the piece also have a form of presence, as does the big piece of the border wall. These also lend an authenticity to Carne y Arena.

+++

Peeper Versus Ghost

Alejandro's sub-title for Carne y Arena is "Virtually present, physically invisible." VR changes the nature of the audience.

Head-Turn VR makes you a stationary observer, a peeper watching people that can't see you. This is an extended version of your role in traditional cinema or video: you are still in a fixed position, but the screen has expanded and surrounds you. As Alejandro notes: "the frame is gone."

There is something eerie about your role in Walk-Around VR. As you walk, stand or sit, the world visually behaves the way you expect it to. But as soon as you try to touch something or someone, your invisible hand goes right through, like a ghost.

One could also say "virtually present, physically absent" because the viewer's body becomes immaterial as it disappears. If the VR movie is not successful, there is a danger of this absence becoming an isolation, or worse an alienation.

+++

A New Cinema

It's often been said that Virtual Reality can be a great medium for empathy. Carne y Arena shares a key feature with most films: identification with the characters. The power of the VR comes from your identification with the immigrants.

In Head-Turn VR empathy sometimes comes merely from feeling the presence of a fellow human being, be it a Syrian refugee or a Masai tribesman.

In Carne y Arena, the empathy comes from your experience, from literally walking alongside them, and getting arrested with them.

The strength of Carne y Arena also comes from the intelligence of the artists in combining real elements with virtual ones, starting with the border fence, and the personal effects of the immigrants, and having the audience wait in the holding area.

The bare feet in sand is a brilliant design move, because it superimposes the virtual desert with the real sand. Having the video portraits of real immigrants on the way out brings us back to the presence of real immigrants after walking with virtual characters. This is part of the job of VR cinema makers: to tear down the wall between the real and the virtual wherever possible, and artfully combine the virtual with the real.

+++

Alone Again

An essential aspect of VR is that, unlike movie audiences, the VR viewer is alone. We can imagine future VR projects that may combine audience members who can interact as avatars, like videogamers do now. But at present the VR audience member is alone with his or her headset. This takes us back to the early days of cinema, before the Lumière brothers invented public screenings with projectors. VR is very much like the Edison Kinetoscopes in the Nickelodeon parlors in the early 1900s.

Alejandro G. Iñárritu and Emmanuel Lubezki and their collobarotors are to be congratulated for creating a ground-breaking masterpiece of early VR cinema. Carne y Arena will appear in future cinema history books alongside the pioneering works of Edison and Lumiere.

Bravo.

+++

+++

LINKS

CARNE Y ARENA PART 1 - VR BY IÑARRITU & LUBEZKI

+++

You can see Carne y Arena at the LACMA (Los Angeles County Museum of Art) or at the Fondazione Prada in Milan. All reservations are made online on the links listed below.

MILAN show

Tickets for "Carne y Arena" in Milan

LACMA show

+++

WIKIPEDIA

+++

REVIEWS

Carolina A. Miranda - LA Times

+++

felixandpaul.com: MAASAI

notesonblindness.co.uk: NOTES ON BLINDNESS: INTO DARKNESS

+++

thefilmbook

VR Cinema 1: Google Cardboard

VR Cinema 2: Image Spheres

VR Cinema 3: Cameras

VR Cinema 4: Content

VR Cinema 5: Futures

Carne y Arena PART 1 - VR by Alejandro Iñarritu with Emmanuel Lubezki

Carne y Arena PART 2 - Notes on Design of VR Cinema

+++

+++