IBC - 1. Sensors, Screens, Boyle, Bennett

The IBC Show is the occasion to review the current themes in cinema technology, and to peek into the future.

The IBC Show in Amsterdam, which ended last week, is a wonderful place to see all the latest offerings in cinema technology. It is the occasion to reflect on the current themes in cinema technology, and to peek into the future. This is the first of several posts about what struck me at IBC this year:

PART ONE

1. HDR

2. Full Frame

3. Hydrogen Buzz

4. Netflix Effect

5. Direct View

6. HDR and fps

7. Geoff Boyle

8. Bill Bennett (and Tony Davis)

+++

1. HDR

The first buzz word of IBC this year was HDR.

HDR stands for High Dynamic Range. Professional digital cameras – not to mention film negative -- have been capable of an extended dynamic range for years. HDR innovation at IBC was therefore focused on workflows and post-production tools to extend the range of blacks and whites on cinema screens and home TVs. Of course there is an economic incentive for all this HDR promotion: the hope of selling a new generation of TVs to millions of consumers.

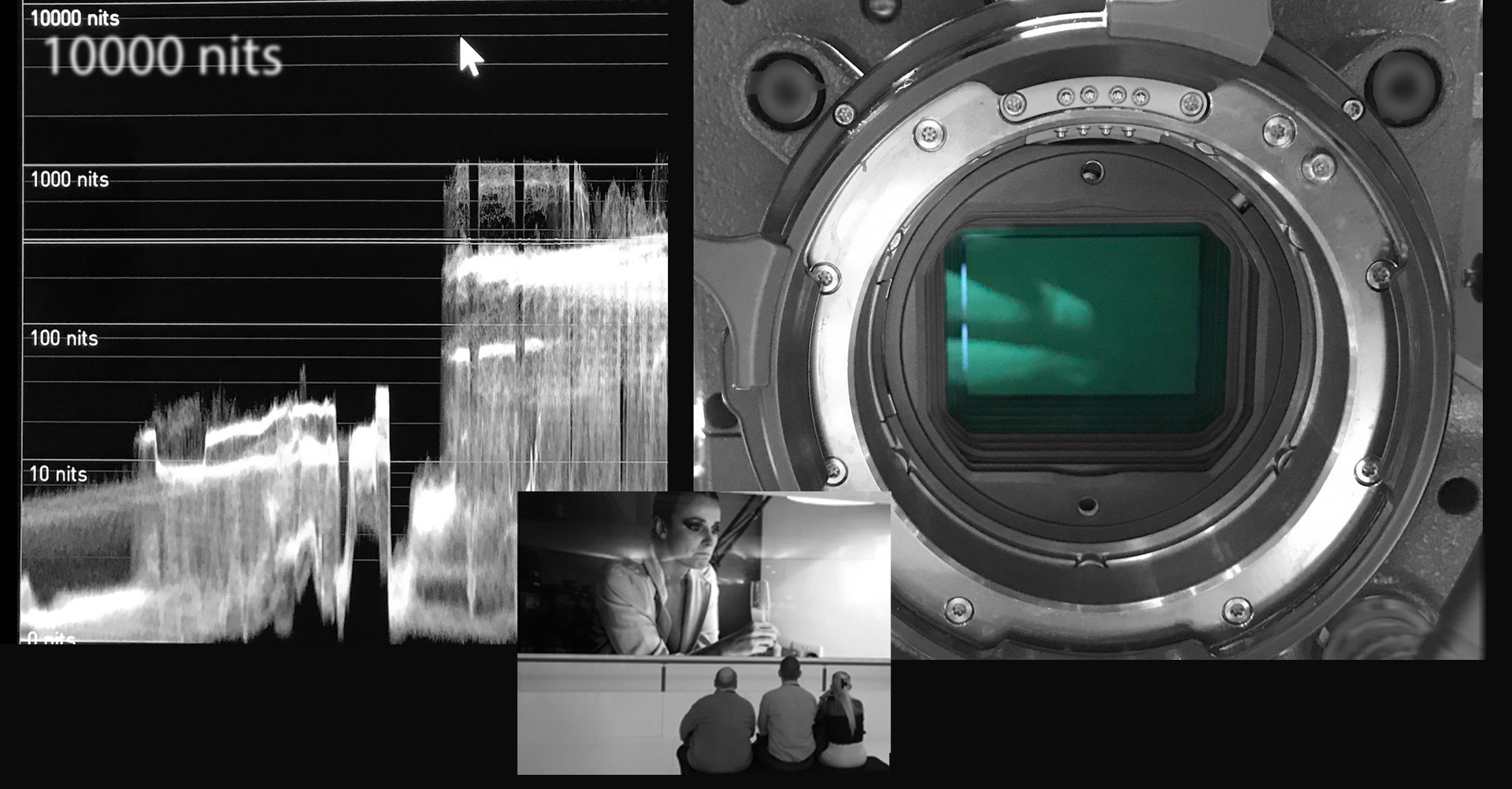

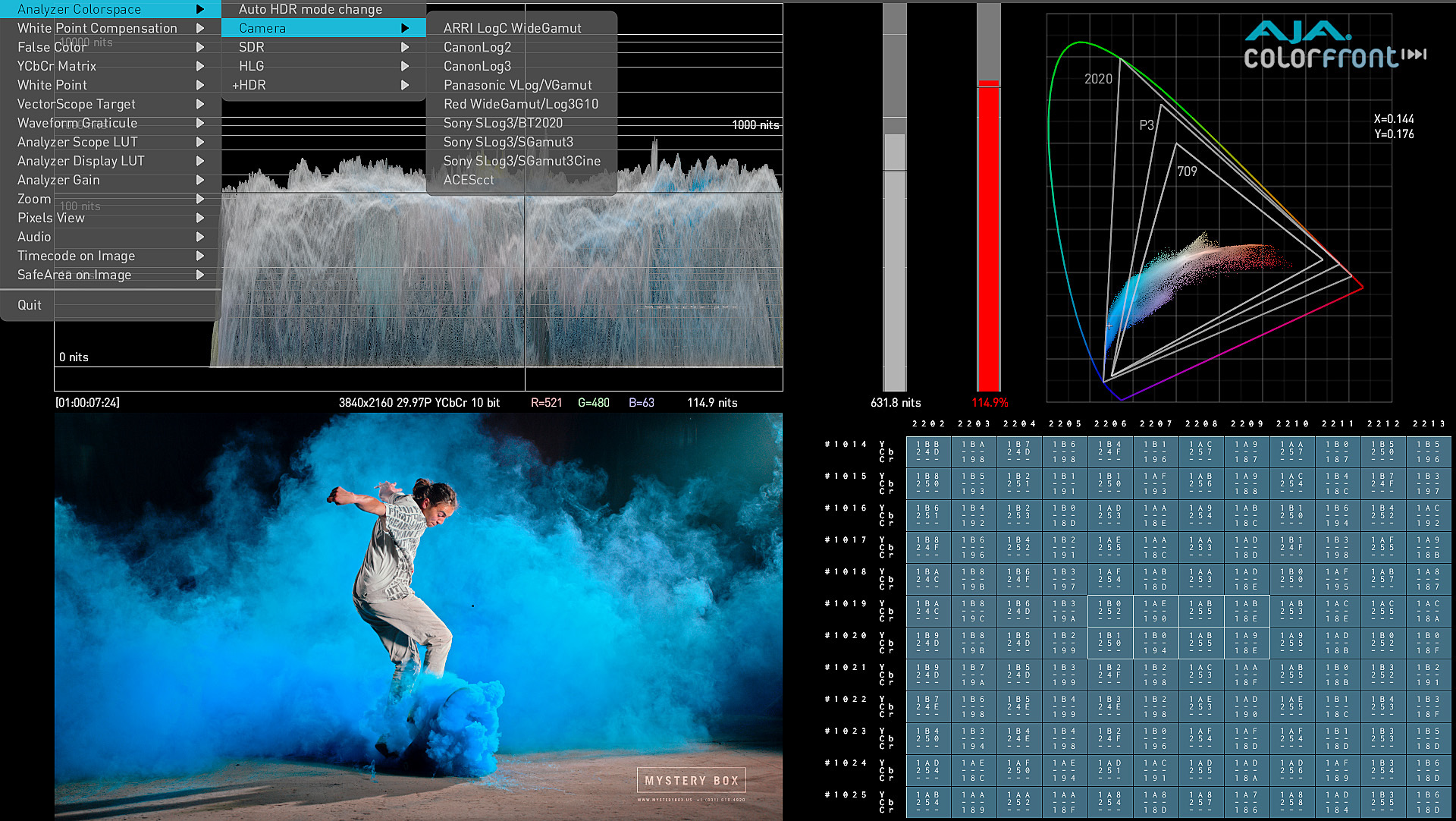

Bryce Button gave me a demo of the AJA Image analyzer, which includes technology by my friends at Colorfront. The unit allows you to visualize whether the image's color gamut fits into the wide triangle of the 2020 emerging TV standard, the medium triangle of the P3 cinema projection standard, or the narrowest triangle of the 709 traditional TV standard (upper right on the image above).

The Image Analyzer can also measure the nits of an image source. Nits are units of screen illumination. The traditional standard for cinema projection is 48 nits (or 14 foot lamberts for peak whites). During IBC, there was an HDR screening using Christie Laser projection at 80 nits. HDR video monitors can go from 400 to 1000 nits, and there is even a Sony prototype at a blinding 10 000 nits. For reference, a bright laptop display is about 300 nits.

Bryce told me that the Image Analyzer is useful for measuring and analyzing camera log inputs, and inputs of varying dynamic range, including SDR (standard dynamic range), Dolby's PQ (Perceptual Quantizer) and the BBC and NHK's HLG (Hybrid Log-Gamma). PQ and HLG are alternate systems devised to adjust the video signal to the capabilities of the display, be it screen, television or smartphone.

+++

2. Full Frame

The other IBC buzz word was Full Frame.

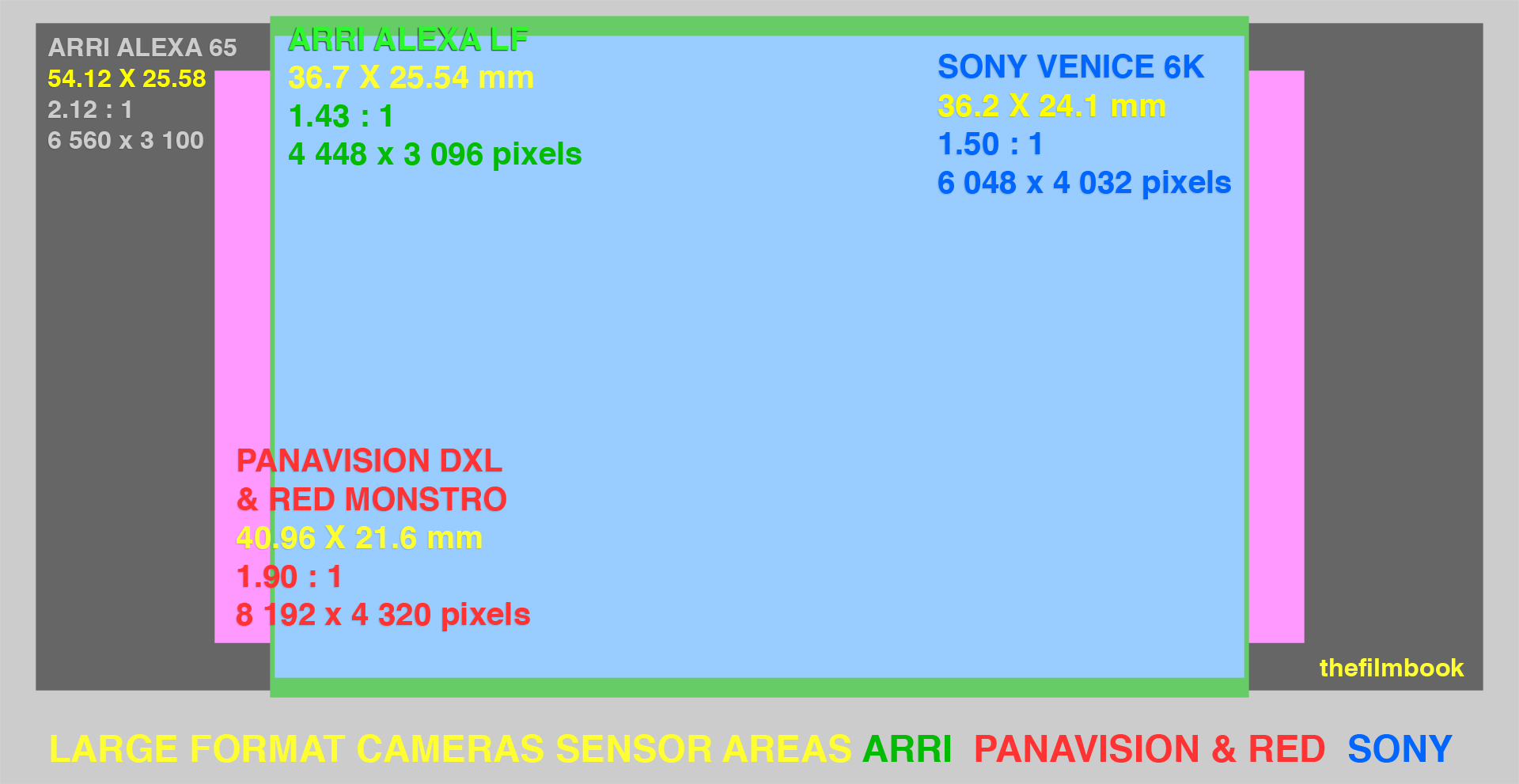

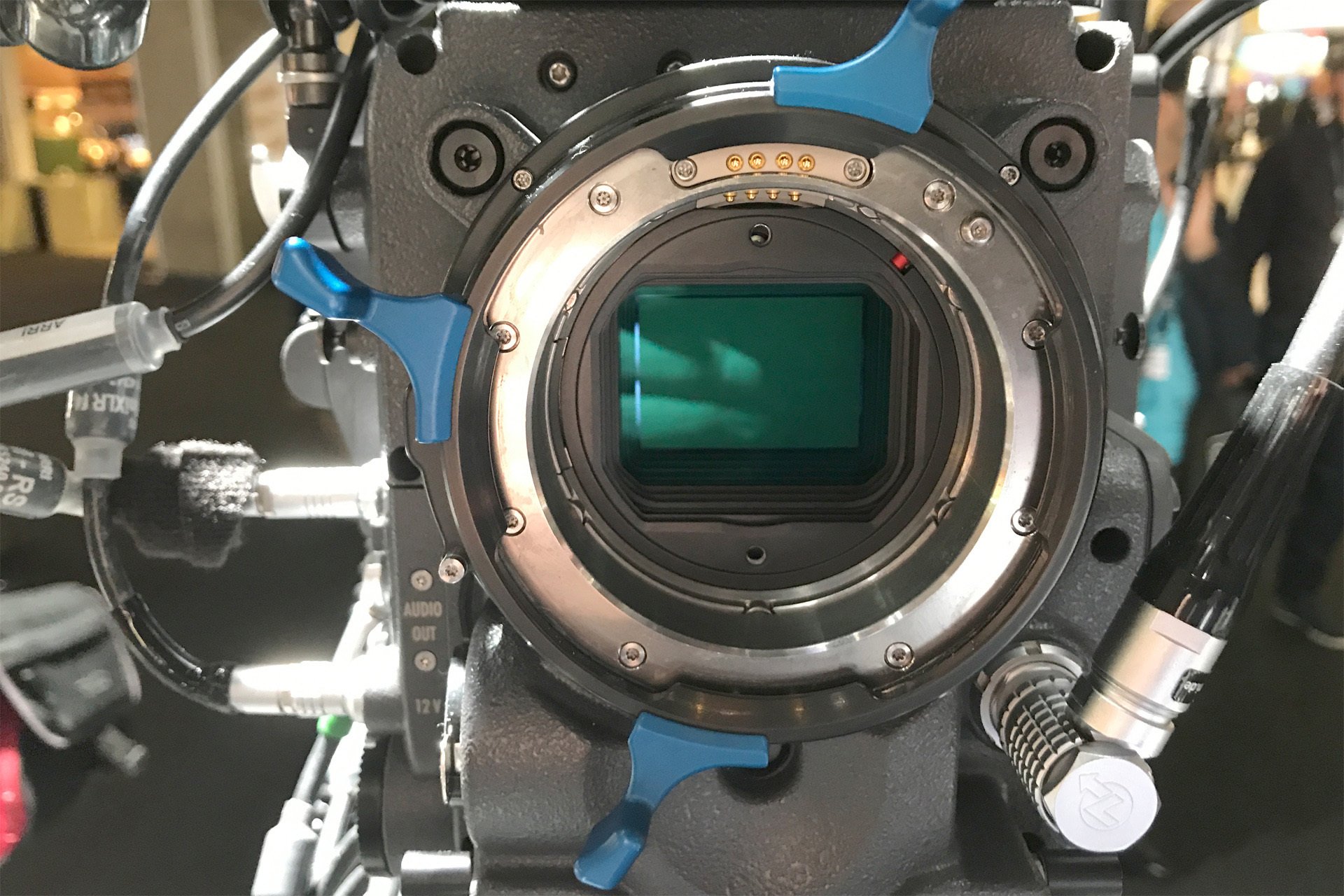

Most lens and camera manufacturers at IBC were proposing image circles and sensors covering Full Frame -- the 36 x 24 mm traditional still photography format that is about twice as big as traditional Super 35. The Full Frame products included brand-new anamorphics, which I will cover in an upcoming post.

Among high-end cinema cameras, Red has been a pioneer of large format sensors, starting with the Dragon in 2015, and then the Monstro in 2017, which Panavision has modified and offered as its DXL. Sony introduced the Venice last year, and Arri's Alexa LF was introduced this year. In the diagram above, I compare the sensor areas, aspect ratios and pixel outputs of these full frame cameras, and also include the largest digital cinema sensor, the Alexa 65, which was introduced in 2014.

The Alexa LF, Sony Venice and Red Monstro/Panavision DXL are all about the same size, the difference lies in the number of pixels output, which is an indication of the size of the photosites, the light sensitive elements on each sensor. Across roughly the same width of 24-25 mm, the Sony Venice fits in about 6 000 smaller pixels, where the Alexa LF fits about 4 500 larger pixels. The Red Monstro (and Panavision DXL) has the greatest pixel density with 8000 pixels across 41 mm.

Larger photosites usually imply greater dynamic range, while smaller photosites can add finesse to an image. It may be that more photosites could also help reduce noise; a Red demo by Dan Duran and Alan Zarnegar showed an impressive reduction of noise when downscaling from 8K to 4K.

+++

3. Hydrogen Buzz

Red's upcoming Hydrogen phone created a more discrete buzz at IBC. Thanks to my friends at Red, I was able to briefly check out a prototype of this cool phone, displaying striking 3D holographic images without glasses, and we even had a 3D photo taken with it.

It is logical to have tablets and smartphones to monitor and control camera systems. Mikael Lubtchansky's foolcontrol app allows you to modify all the menus of a Red camera on an iPhone, Android, or computer via wifi or the internet. The Hydrogen is the first attempt by a camera manufacturer to make a smartphone remote designed for its camera. Other future uses of the Hydrogen One will be to integrate it into the camera, for example as a viewfinder.

I really want to get a Hydrogen, but I probably can't afford it. :)

+++

4. LF for Netflix

In the past few years Netflix has become a major investor in the production of features and series, spending 6 billion dollars on video content in 2017. Netflix policy requires all of its own productions (but not its acquisitions) to shoot in 4K or UHD, an arbitrary rule that excluded projects shot on the Alexa, with its lower pixel count.

I strongly feel that it is wrong to impose pixel counts that limit filmmakers’ artistic and technological choices. In any case, the reality is that Netflix’ rule is pushing many Alexa productions towards the new Alexa LF, with its 4.4k sensor (4 448 x 3 096 to be exact), which has been approved by Netflix.

+++

5. Direct View

It’s important to remind everyone that TV technology currently equals or surpasses cinema technology in all aspects except size. The latest models of TVs have a wider color gamut, higher frame rates and much more dynamic range than the latest Laser projection, which is currently set at P3 color, 24 fps, and about 100 nits (with the best Laser HDR). Current TVs can offer 2020 color, 120 fps, with thousands of nits. To me the great thing about HDR for cinema is getting good blacks; I'll happily trade you 50 nits of highlights for deep blacks. :)

Simply put, Direct View is a huge TV that can offer TV quality to a large audience in a screening room. A key advantage for cinematography is that Direct View can offer nearly perfect blacks, by simply turning off the LEDs. Samsung is the pioneer of Direct View, and in an IBC panel representative David Hernandez stated they presently have some 19 cinema screens in place.

Sony showed its version, the Crystal LED Display, at IBC, displaying 60 fps footage to reduce strobing. This Direct View screen was set at an impressive 1000 nits, enough to be viewed in the brightly lit Sony booth, despite light reflections on the screen. The Crystal LED at IBC was 6.8 meters x 2.7 meters. The screen is made up of modular panels, and it can be resized by adding or subtracting panels. As of now, Oliver Pasch from Sony explained during a panel that some of their systems have been sold to wealthy individuals for private screening rooms.

+++

6. HDR and fps

One of the disadvantages of a very bright screen is increased strobing of moving objects, a complex phenomenon that increases with speed and contrast. Technologist Pete Ludé attributes this to the Ferry-Porter law. Pete told me that the best solution for Direct View would be to shoot and display at higher frame rates. Shooting at a high frame rate eliminates judder, while displaying at high fps eliminates strobing. Pete mentioned that the old school way would be to ask filmmakers to do slower camera movements. :)

Fast movement remains a difficult problem for the adoption of higher screen illumination on big screens. As the brightness of our movies increases from the classical standard of 48 nits to Laser projection of about 100 nits, and then to Direct View at 500 or 1000 nits, we will have to lessen or eliminate judder and strobe.

+++

7. Geoff Boyle’s Tests

A key cinematographer presentation at IBC was given by Geoff Boyle, NSC, and Bill Bennett, vice-president of the ASC. Geoff is also known as the creator of the CML site and mailing list. (We will cover another cinematographer presentation of Full Frame anamorphics in part 3).

+++

At IBC Geoff projected a series of exposure bracketing tests that he shot with 14 different cameras from Arri, Blackmagic, Canon, Fuji, Red and Sony, among others. The tests reveal the dynamic range and color tracking of each camera.

Geoff stated that while the Alexa appeared to be the reference in dynamic range, "other" cameras were better at color tracking. He also pointed to the impressive results of the modest Fuji X-H1 and Ursa Mini Pro from Blackmagic, saying of the Ursa: “Is it an Alexa? Of course it’s not, but it’s one tenth of the price.”

Geoff finished his presentation with an impassioned plea to look at the images, and to forget the pixel count, claims about stops of dynamic range, and other specification numbers. Or, as he put it: "Fuck the numbers!"

+++

8. Bill Bennett, ASC (and Tony Davis)

At IBC, ASC cinematographer Bill Bennett presented Flamenco, a beautifully-lit short film he shot that was directed by Demetri Portelli. The film offers a great demonstration of RealD TrueMotion, a synthetic shutter system developed by Tony Davis. (Davis' system started as Time Shaper and became TrueMotion when his company was acquired by RealD).

At IBC Bill screened both Flamenco, and a very helpful 11-minute TrueMotion Explication that shows detailed comparisons of excerpts of some of the footage with and without the synthetic shutter.

The TrueMotion workflow runs like this:

-- Shoot at 120 fps with a 360 degree shutter.

-- Process the footage for desired fps output (24 fps or higher)

-- apply a chosen "synthetic shutter" to render motion

-- output the footage at the selected frame rate.

With a 180 degree shutter half the time, half of every motion in the frame, is not recorded; shooting with a 360 degree shutter insures that there is no motion that is not recorded by the camera. The 120 fps rate represents a high temporal resolution; in other words, each frame of a 24 fps output can be created by "synthesizing" or combining information from 5 frames at 120 fps.

To me, TrueMotion is a brilliant invention that addresses something that is both subtle and essential to cinema: the rendition of motion, without changing static elements in the frame. Cinematographers have long increased or decreased motion blur by opening or closing the shutter. TrueMotion gives filmmakers an enlarged and refined palette of motion rendition, with some twenty different "synthetic shutters" that build their distinctive temporal shapes with different mixes of surrounding frames, different attacks and decays.

Bill Bennett's work on Flamenco offers an intriguing glimpse of a technique that promises to extend the temporal art of cinematography. Bill added that he sometimes uses TrueMotion on car commercials to reduce the flicker of dashboard lights at odd frequencies. TrueMotion also offers a possible solution to the judder and strobing that might be heightened by HDR, for those productions willing to shoot problematic scenes at high frame rates.

Could it be that one result of HDR will be to push filmmakers to shoot at higher frame rates?

+++

PART 2 : IBC - LED, DI, VFX, Art, Robby

+++

LINKS

HDR

thefilmbook: Colorist Peter Doyle - HDR, Vintage Workflows, Etiquette

thefilmbook: IBC: More Color, More Contrast

ascmag.com: President’s Desk: The Blind Awakening

Full Frame

thefilmbook: VENICE Camera - 1. Speaking with Sony Experts

arri.com: Arri Large Format page

Hydrogen Buzz

mikasky.free.fr: Mikael Lubchantsky's apps

youtube: RED Hydrogen One Unboxing! (Houdini Edition)

LF for Netflix

thefilmbook: Cinema 2018 - 9 Key Trends / Challenges

Direct View

samsung.com: Samsung Direct View page

pro.sony: Sony Crystal LED page

thefilmbook: IBC: 4K and better pixels

HDR and fps

frontside.de: 35mm Recommended Panning Speeds

Geoff Boyle

gboyle.nl: Geoff Boyle NSC FBKS

cmltest.net: Digital Cinematography Camera Evaluations 2018

cmltests.net

Bill Bennett (and Tony Davis)

wfb4.com: Bill Bennett ASC page

vimeo.com: RealD TrueMotion Explication

reald.com: RealD TrueMotion page

Note: you can find more technical details about TrueMotion

on the archival tessive.com website:

-- Time Shaper ( aka TrueMotion) technical info

-- Different Synthetic Shutters

thefilmbook: A Revolutionary Screening From Ang Lee

+++

Unless otherwise indicated, all images are copyrighted by Benjamin B

Feel free to share images on the net with the following credit:

(credit Benjamin B, thefilmbook)

+++

thefilmbook: IBC - 2. LED, DI, VFX, Art, Robby

+++