On Body and Soul - Interview with Director Ildikó Enyedi

Hungarian writer-director Ildikó Enyedi shares some of her insights and approaches to her film On Body and Soul, which was nominated for an Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film.

Ildikó Enyedi is the writer and director of On Body and Soul, the poetic Hungarian movie nominated for the Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film. I had the privilege of speaking at length with Ildikó about her highly original love story. I saw the film at Camerimage where Máté Herbai, HSC won the Golden Frog for On Body and Soul's wonderful cinematography.

On Body and Soul is a love story between two loners working in a slaughterhouse: Endre (Géza Morcsányi), an administrator with a handicapped arm, and Maria (Alexandra Borbély), a quality inspector who suffers from Asperger's syndrome. Endre and Maria are drawn together despite themselves, when they discover by accident that every night they share identical dreams of being a stag and a doe in the woods.

On Body and Soul starts with a dream, but very quickly confronts us with the mystery of death. Footage shot in a real, pristine slaughterhouse shows us a living cow, and, very soon afterwards, its lifeless carcass. Although the filmmakers are careful not to show the killing, a brief scene of an efficient worker cutting up the carcass is a powerful image for a body without a soul.

This initial jolt sets the scene for a film that masterfully interweaves parallel stories, shifting between deer and cattle, between the everyday lives of Endre and Maria, between humdrum reality and luminous dreams, between people and animals, between humor and poetry, between body and soul. The film keeps us wondering until its very end about the power of love to overcome self-imposed isolation. After seeing it three times, I consider this film a masterpiece.

+++

Trailer

watch on YouTube

+++

Ildikó Enyedi

Ildikó Enyedi is a leading Hungarian screenwriter and director. She directed seven features between 1987 and 1999, including My Twentieth Century which won the Camera d'Or at the Cannes Festival, and Simon the Magician.

It took 18 long years before the director could get her next feature project produced, On Body and Soul. During this difficult period, HBO hired her to direct the Hungarian version of the series In Treatment between 2012 and 2014, and Ildikó also taught at the University of Theatre and Film Arts in Budapest.

On Body and Soul won the Golden Bear at last year’s Berlinale, where Alexandra Borbély also won Best Actress. Máté Herbai’s cinematography was awarded the Golden Frog at the Camerimage Festival, and was also nominated for the ASC Spotlight Award.

If you haven’t seen the film, I strongly urge you to view it on Netflix in the US, or on iTunes, or via cable or streaming elsewhere.

I should also warn you that this interview with Ildikó contains some spoilers.

+++

+++

Interference

Benjamin B: Why did you call your film On Body and Soul?

Ildikó Enyedi: Like so many things in this film, it was very instinctive. I thought of changing the title, but I kept it because it’s exactly what the film is about.

It’s not so much that we have a soul and we have a body, it’s that the thing that we call our selves is a third thing, it’s the interference of the two. I wanted to show that we are somehow the interference of body and soul.

It was quite important for me to show those things that were just about the body, by putting the accent on the soul. For example, by showing at length the face of a cow before it is shot, but not showing the shooting itself.

+++

+++

Chosen Blindness

The film starts with a dream, but very quickly you make us face the mystery of death, not a fictional death, but documentary footage of a very real slaughterhouse.

Enyedi: Slaughterhouses exist, there are people working there. It’s a very normal workplace, but we are horrified when it is shown. We want slaughterhouses to exist, but we don’t want to show them. And this is just one tiny example of the long, long list of things that we want to exist, but decide not to see, not to think about. This is our decision, and if a culture is built on this sort of chosen blindness, it makes us neurotic, because we are not present in our life.

An animal is not just sweet and cute. An animal like a deer or a bull is 100% present in the moment all the time, facing life with its whole body and soul. But we are not fully present, like animals are.

The film poses this lack of presence from the start, but you evoke these ideas with images -- it’s not an intellectual film.

Enyedi: We wanted to incite in the spectator all sorts of very elementary feelings, and humor is an important part of that. But I didn’t want to push anything in the viewer’s face to tell them what to think. The viewer’s thinking should be private, personal... after the film.

You show us something invisible by showing us something visible?

Yes. Thank you. Exactly.

+++

+++

Transcendent Love

Are the dreams a way of saying that love has chosen Maria and Endre --and that is coming to them from outside their world?

Enyedi: Yes, it’s a natural force. It’s another name for the transcendent.

You mean the dreams?

Enyedi: Yes. It’s not a human choice like: "Okay now, I decide". I never thought about it during the making of this film or during these many, many interviews, but the work of Simone Weil was very important for me as a teenager…

I am a big fan of Simone Weil. I once made a web site about her philosophy.

Enyedi: Really? This a Simone Weil film. She makes a distinction, and Rilke has it too, between the holy -- the transcendent -- and morality. The transcendent is on another level, it is a very direct connection to the elementary forces of nature. The transcendent is wider, truer and more basic than morality, which is trying to set a code for social life.

The film wants to communicate, to anybody who is watching it, that everyday life is missing something. We are very politely softening the edges and covering the essence because it’s too strong, too powerful. The film is about discovering that essence.

Through a love story...

Enyedi: When you are in love, nothing is hidden. It’s a moment of truth. You are very naked, your partner is very naked, the world around you is very naked. It’s rare, for the reason we just spoke about.

And Maria, when her soul is opening up, makes herself ready for real love through very basic bodily experiences: touching things, touching the grass, touching the fur of a soft animal, accepting a touch, or simply just feeling the sunshine on her skin. These are very new experiences for her, because she approaches life from a very practical point of view, to not get lost in it, for her own safety.

+++

+++

Working with Actors

For the two main roles, you chose a very accomplished stage actress and a first-time actor.

Enyedi: When you are working on something like this, you just want the best, wherever you find it. It is a bit of a sleepwalker process, but at the same time you activate all your professional knowledge.

I knew that even if I could find a wonderful Maria, that role wouldn’t be possible with an amateur, because if someone were that shy, then I wouldn’t bring that person on set, because it’s a brutal thing to act in front of a camera, it’s not without danger. So I knew that for Maria I needed a professional. For Endre I knew it could be a professional or not.

What made you choose Géza Morcsányi, a non-professional, for the role of Endre, the male lead?

Enyedi: Sometimes you just know. Sometimes you shoot a lot of tests. In his case I made just one test, but I did the test mostly for him, so that he could be calm, so that he could feel that he could do it. I am very happy with what he did, with his whole presence on set, on screen.

Is the danger with an amateur that they try to act?

Enyedi: Géza is a very intelligent person, he is also a theater author so he has watched rehearsals all his life. He knew what acting is. He knew exactly that he shouldn’t even try. It’s not his way. If he had tried to imitate acting, it would have been the end. On set, I had to give very few and very practical instructions.

How did you work with Alexandra Borbély, the lead actress?

Enyedi: It was different with each actor. It’s like two people speaking different languages, so I prepared with each of them separately. With Alexandra we did very serious work before shooting, which was part conscious, part unconscious: just spending time together, speaking together, finding clothes, making photos, and looking inside her to find this Maria somehow in her.

Alexandra didn’t play Maria, she transformed into this Maria, because she found the clue for it. It was an amazing process that I will always remember, to see how a great actress can work. On set it was already done. This Maria got her own life and I barely had to say anything. There was no need.

Géza got a lot from Alexandra, they had a mutual respect, but for sure an amateur cannot give the sort of support to a professional actor that she’s used to. So Alexandra was isolated, but Maria is an isolated character, and the whole film is about the difficulty of reconstructing in daylight the harmony that they have in the dream, so it was informing the topic of the film.

+++

+++

Exact Shots

Looking at the film’s shot breakdown – its découpage -- it is very “cut”. It is constructed by editing many short shots, as opposed to long ones

Enyedi: The intention is to be exact, like a poem is exact. A poem is never something dreamy. It is very, very exact. You can’t change a word or a line, or leave some things out, because the whole construction would fall apart. This sort of exactness was my goal.

How did you work with your cinematographer, Máté Herbai?

Enyedi: I just spoke about this cultural habit to close our eyes, if something is uncomfortable. Máté has the power of the eyes of a child who hasn't learned yet when not to look, when to close his eyes. He is able to really see what is around him.

Máté is a very pure person with a very authentic tenderness towards the world, which was very much needed towards everything, not just the protagonist, not just the deer and cattle, but also towards the objects. His whole personality is in the film.

How did you prepare with Máté?

Enyedi: With Máté, from the very start, we swore not to think about any style, because a style is on the surface and would make the whole thing stiff, and would just blind our focus, which was at every moment on that sort of exactness.

Did you storyboard?

Enyedi: Yes. It’s a way of thinking with a pencil in hand. It wasn’t a fancy storyboard with a storyboard artist, just my own very basic drawings. In the evening after every shooting day, I would redraw the storyboard, because every day brought new ideas.

In the morning Máté and I went to set in the same car, and we discussed this final version, and redrew it. So when the car stopped, we had the plan. For sure we weren’t too rigid to not depart from the storyboard, but it helped us to think.

Did you talk about light with Máté?

Enyedi: Light is such a powerful dramaturgical tool. For example, when Maria is in the bathtub, we see Endre at home just sitting on the couch and watching television, jumping from one channel to another and then switching it off. The way Máté lit that scene so perfectly expresses the weight, the loneliness, the wound:

Máté never wanted something fancy and visually attractive. It's a humble approach. He just wanted to express something very much. This is a character trait that I needed so much; without that sort of approach, the whole filmmaking would have been a big struggle.

+++

Coverage

Many of the dialogue scenes in the cafeteria, with the psychologist, and between Endre and Maria have a very classical coverage.

Enyedi: Máté, and everyone in the team, understood very well that we needed a humble approach. Not to be afraid to be classical, sometimes to use tools that are not very shiny and not very cool, but to just consider if this is the best for that purpose.

We always thought about the meaning of every take, about its meaning in the scene and the scene’s meaning in the whole construction, so as to be articulate and tell what we wanted to tell, and no more or no less than what we wanted to tell.

For example, the camera is never observing the animals in the woods or the slaughterhouse. There are many over the shoulder shots of the animals. But there are many observing camera positions from outside the window, when we show the two people with their daily routine in their miserable, lonely two apartments: the one toothbrush, falling asleep after two beers in front of the television etc..

+++

+++

Secondary Characters

You have said that you like secondary characters, because they offer a little glimpse in someone’s life. I’m thinking for example of Sanyi, the new male hire who Endre mistakenly accuses, and then apologizes to.

Enyedi: When you have a secondary character there isn’t much time. In this case, for each of them, I showed one color first, and built up a sort of conscious prejudice, and then I wanted to give a glimpse behind it. It happens so often in real life that, when you peek behind a person, what you find is much kinder and more vulnerable, and the reasons for behavior are much more understandable.

I have a former student, a young director who is quite a sarcastic guy and not easily touched by anything and he watched the film, and it’s so wonderful what he said, I really will remember it always. He said: “I saw that people are good and that love is possible”.

Wow.

Enyedi: I was so happy because these simple things are so rare, for example, just to apologize, to say: “I’m sorry, I made a mistake”. And immediately we are not imprisoned any more in our little roles, and fresh air comes in, and a human moment is possible.

+++

+++

Towards the End

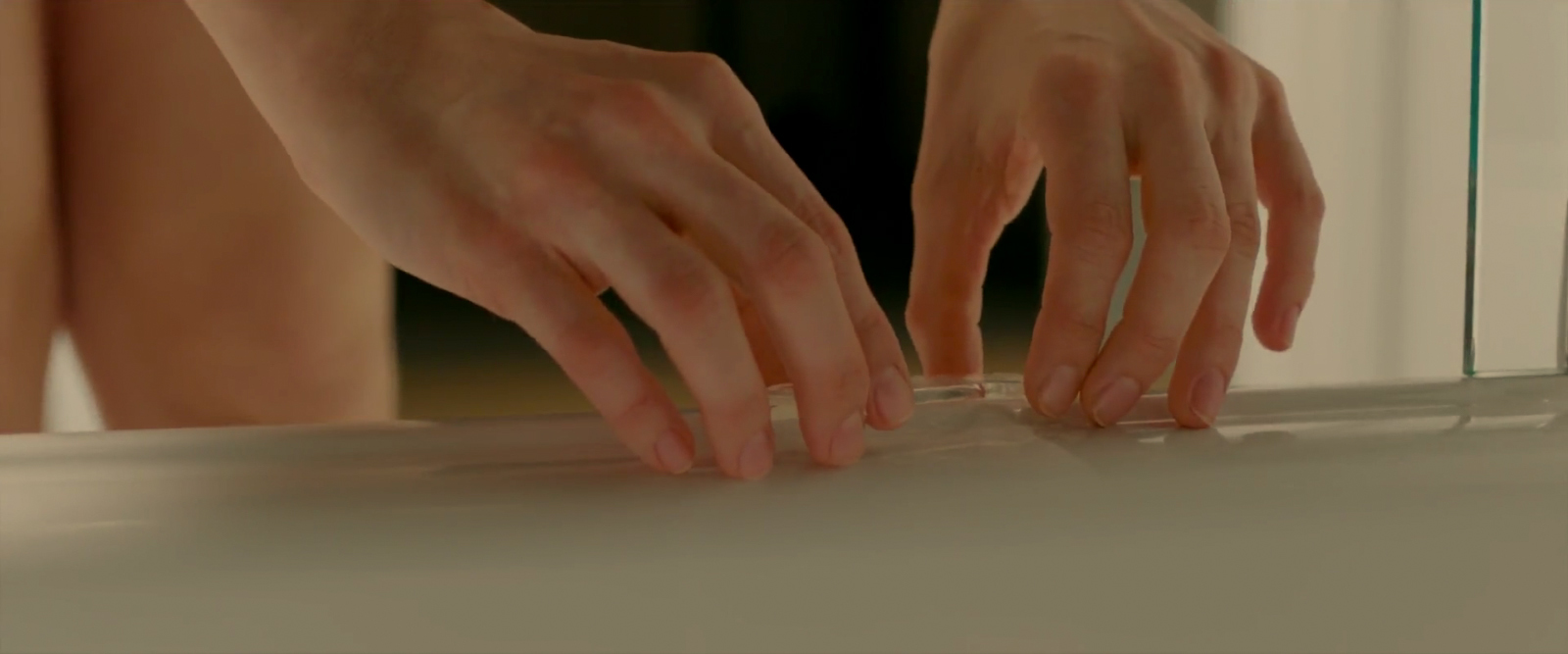

There is an extraordinary scene when Maria attempts suicide. The moment brings forth a strong combination of emotions: suspense, fear and shock -- but also unexpected humor!

Enyedi: The suicide is a logical next step for Maria because she’s been refused, but she has gone so far that she left her little shelter. She’s out in the world and she has no way back.

The main thing was not to have a climax, but to have a relentless, even pace. In the same way as when we show the slaughtering: it’s morning, they have their coffee, they go to their work place, they kill animals, they take a cigarette break, there is some music coming from somewhere, the bulls are politely waiting, standing and then the killing continues, and everything is the same pace. I could call it a Simone Weil approach: not to make extra drama of something that is dramatic in itself.

To show the extraordinary in the ordinary.

Enyedi: Exactly. So it was the same thing for the suicide: she washes the dishes, gathers the clothes from the balcony, breaks the glass, cuts her wrist, with the same pace. It was a very, very delicate thing to edit.

It's an emotional roller coaster. You don’t know in one second whether you want to laugh, or be moved by the drama. It was really in the tiny nuances. For example, there is a pan from the wrist to Alexandra’s face, and we see her breast. I really didn’t want to show any extra nudity, but I felt that if I cut there, it would make you a bit more aware of the technical: "Oh, sure we are sitting in a cinema and watching a film, it’s not really happening". So every cut can be very tricky in this way.

And then the phone rings.

Enyedi: And even the ring tone of her phone was a dilemma for me. We made it with the sound designer, I wanted a very normal ring tone, but at the same time to show that this is an alien object for her. It’s a silly little happy dumb ring tone. Absolutely not Maria. We were afraid that it would be too much for the suicide, too funny and that it would kill the whole scene. In my opinion this little sparkle of humor doesn’t kill the emotional part of the scene.

There is a very deliberate camera movement down Maria's body, the only moment of nudity in the film. Her bleeding body evokes the slaughterhouse scene at the beginning. Her body may soon become lifeless, like the animals we've seen earlier.

Enyedi: Yes. It’s not by chance that she attempts suicide in this way.

You are really manipulating the spectator: we're dying for Endre not to hangup. It’s an amazing cliffhanger.

Enyedi: Thank you.

+++

+++

Moment of Truth

You have said that life on the set of film is a moment of truth.

Enyedi: Yes. Your every act, every gesture, every word has an impact on everybody else around you and can enhance or jeopardize a common effort -- the film you are working on. It is a very sensitive situation and you just get to know a personality, after several days of working together on set, very deeply. You can’t really be wrong.

Very quickly you can realize if somebody, for example, is not behaving well with the team and has bad habits. And you have to make the person realize that this is not the place, and that he or she gets a chance to become better as a person, and immediately in this same moment he can feel how much more joy the work means and how that’s less tiring.

Every day after shooting, I bring home a ton of extremely touching moments, when you see people focusing with their whole soul on something that you can’t really describe yet, with the hope that at the end of the process there will be something rewarding in it: something which will make other people happy. They are just focusing on what they are doing and how to do it in the best possible way. It is like forgetting yourself, like a child forgetting himself in a sandbox. It’s beautiful even the movement of the crew is beautiful.

It’s not just me who is saying this. There were crew members who said that this was sometimes a transcendent experience. For example, in the national park where we shot with the deer, the silence of these big woods was very powerful for everybody.

You were bringing this dream to people participate in creating it. Like Endre and Maria, maybe you were all trying to share the same big dream.

Enyedi: Yes.

+++

Always Maria

You were like Maria once?

Enyedi: I always will be Maria. I’m an only child, I started reading very early, and books were the universe for me. I learned to just survive difficult social situations like parties and so on.

What is in the film as Maria's exchange of experience, I had with my children. If you have a small child, time slows down and space becomes much much larger. As a present, you get a chance to relive your experiences, I got a chance to relive childhood; in my case the second time was much more relaxed.

So I learned from them. When my children were born, for example, I learned to swim. I learned to ride a bicycle to be able to go with them. This is an immense freedom for me, I go everywhere on bicycle in Budapest. I also go on tours in the countryside, this is something very liberating.

Your children brought you out into the sunshine?

Enyedi: Exactly.

+++

Being a Man

What is your next project?

Enyedi: We are working on the adaptation of a Hungarian novel that I wanted to make as my second film, it's called The Story of My Wife by Milán Füst. The story is told by the husband. It’s really about a male soul, the vulnerability of a grown-up man. I think I know a lot about it although I am not a man. I want to enter into the mind and soul of a man of about 45.

You want to imagine and experience what it is to be a man?

Enyedi: It is connected to the birth of my son. When I had him in my arms for the first time, it was like a huge mountain of knowledge, which appeared from I don’t know where. It was really heart-breaking. I just said: “Oh my God, how difficult it is to be a man. How vulnerable a man can be".

I have a lot of understanding for this sort of struggle how men try to do the right thing, lead the right life, to live up to what society wants from them, their partners, the women want from them, it’s not so easy.

At this moment many people are talking about the difficulty of being a woman in our society.

Enyedi: It's a thing we have to go through. I think it’s difficult to be human. And it’s nice that it’s so difficult, because that means that we have something to do during all the years we live!

+++

A big thanks to Ildikó Enyedi and Máté Herbai

Set photographs and images courtesy of Máté Herbai

+++

LINKS

wikipedia.org: On Body and Soul

wikipedia.org: Ildikó Enyedi

YouTube: On Body and Soul trailer

mateherbai.com: cinematographer Máté Herbai

mubi.com: onbodyandsoul

mubi.com: pdf press kit for On Body and Soul

YouTube: "What He Wrote" by Laura Marling

simoneweil.net: About Simone Weil

nytimes.com: Review of The Story of My Wife

+++