Visit with Darius Khondji, ASC, AFC - 2. Sources, Exposure, Contradictions, Directors

The cinematographer shares some practical and aesthetic approaches of his cinematography.

This is PART 2 of the account of my visit with master cinematographer Darius Khondji, ASC, AFC.

+++

Part 1

- The Book

- Teenage Dimming

- Gold and Green

- Placing the Source

PART 2

- Big Sources

- Exposure

- Contradictions

- Directors

+++

1. Big Sources

Benjamin B: Do you recommend that young DPs try using a big source?

Darius Khondji: Yes, an 18K or 24K if you can. I like to use the remains of the light.

BB: In the past, you would sometimes start with a 10K or a 20K far away, and diffuse it two or three times, until there was very little light left.

DK: I often needed that before, but not always these days, because you have to work with the reality of today’s budgets.

But I really like the Tungsten 24K, it’s one of my favorite fixtures. If the budget allows it, I try to have two big sources on a film. Sometimes the 24K is a drop-off for a day, and the rest of the time the truck just has smaller sources, or maybe just one big one. The 24K is very beautiful because it reproduces the sun.

BB: The Fresnel lens is important to you.

DK: I really like Fresnels. The Arrimax are fantastic, but they generate so much light that you have to work them. I don’t like their directional light as much. The 24K big eye has a bigger fresnel than an arc light. I only use it when the story calls for it, on day interiors, and day exteriors too

BB: You use tungsten instead of HMIs on day exteriors?

DK: HMIs are beautiful too, but I tend to use them in indirect lighting or through a lot of diffusion. I put a Lee 159 Straw gel on HMIs to take out a little of the magenta, and every time I put that in, the whiteness of the light reminds me a little of the whiteness of the arc. It makes the HMI a little less electric.

BB: How about LEDs?

DK: I use them all the time. I used nothing but LEDs on the film I just finished with the Safdie brothers in New York... except for one 24K source.

(laughter)

DK: I used to use arcs as big sources

BB: Carbon arc lights. Wow, they’re just about extinct now.

DK: I used to interview my gaffers, and ask if they had one or two people on their crew who knew how to use an arc. And if so, we would put two of them in the truck, and I would bring the arcs out every day, because lighting was very easy with an arc.

You turned the arc on and you got sunlight, a light that was a true sun. You immediately had the right color, no need for gels. But they were not worth using if you were going to diffuse.

BB: What about soft lighting?

DK: Double diffusion is very beautiful. I also really like indirect lighting, it has a feeling of truthfulness. But it depends on the production, sometimes you don't have time for that. But if you stay a long time in a location you can take time to create indirect lighting.

+++

2. Exposure

DK: I like to say that exposure is like a political statement. It’s a manifesto. I read a script for a feature and I imagine how I will expose it.

What bothered me about digital at first is that people would say that I had to expose it fully. I often had arguments with DITs about this. I like to give the exposure a direction, like I do with negative. If you know you’re going to do chiaroscuro and have a very under-exposed image, why open it up with a full signal? Why open up completely when you know that you will only be showing the remains of the light? For me, it’s not Feng shui. I don’t want to impose this on anyone, it's just my way of working.

BB: And the same thing with over-exposure?

DK: For the hot openings outside the jungle in Lost City of Z, I wanted to sense the extreme sunlight. When you come out of the jungle and the obscurity, it’s like a heart beat, you need to feel this contrast.

BB: It was great to see you speak with young filmmakers at the Master Class.

DK: Young DPs are doing great things now. I often hear directors say: "Oh they don’t have the culture of film". I don’t really agree. I think that digital is another culture, a mutation.

BB: This is really a silly question, but would you advise a young DP to use a light meter?

DK: To be honest, I sometimes shoot without a meter, on commercials I’ve directed, with a DIT I know very well. Then I let them control the iris.

But since there are T stops engraved on the lens, why not have a meter? It gives a name to the exposure. It gives you an idea of where you are, like Kelvin degrees.

BB: I was thinking of taking a photo of your meters.

DK: Sure. In my current kit, I have three Sekonic meters, plus a Minolta color meter, and a laser for pointing things out on the set.

I learned to expose with a Weston incident light meter. I knew Nestor Almendros, and he would read the light off his hand with a Weston.

I used to use my incident light meter all the time, now I mostly use my hand. I put my hand in the light and look at it, even on a film shoot. I use my meter at the very end of the process, just before shooting.

BB: Did Nestor Almendros give you any advice?

DK: Not really. I just watched him. He would use his hand, and he would squint his eyes all the time, and I also squint. When you squint, it synthesizes the light. I still have the contrast glass, but I leave it in my pocket. And I squint a lot.

+++

3. Contradictions

BB: You like to use the French phrase “contre-emploi”, which is literally translated as “against type”.

DK: Yes, like when comedy actors are cast in a drama.

BB: One example is taking a big source and diffusing it a lot until there’s only the remains. For me your "contre-emploi" is like doing something and its opposite at the same time, a contradiction.

DK: It’s more interesting that way. We are like that. People are contradictions. Sometimes we feel bad about creating contradictions, because we tell ourselves that we’re not direct enough, that we could work more simply. But I’m like that, and you have to accept yourself as you are. I like to play against type. I love to cover my tracks, so that you can’t really see how the image is created or where it comes from.

One simple example is flashing an image that has a lot of contrast. I made very contrasted lighting, and then I controlled that contrast by flashing the film.

[ Note: Film flashing involves adding a small amount of unfocused light to the negative to expose and therefore lighten and/or color the blacks. Darius often used the Lightflex Varicon to add light in front of the lens.]

Another example is that, in Delicatessen, I used to pull process to soften the image and then contrasted the film print with bleach bypass.

[ Note: Pull processing under-develops the negative to soften the image. In bleach bypass, a processing bath in the film lab is skipped to increase contrast -- by leaving silver on the negative that would have been removed]

For City of Lost Children, I used vintage Cookes and I filtered a lot. In general I had 3 filters, and sometimes 5 in exteriors. So I softened the image when shooting, and hardened the contrast with my lighting, and by adding silver to the print. I hit the image with lighting and silver to increase the contrast, but I also diffused it and lowered the contrast with filters and flashing.

It’s a matter of control in fact. Playing against type is a matter of controlling the image...

BB: There's something painterly about the approach you describe.

DK: I have treated the image like a canvas. I used to be passionate about Pictorialism, where painting and photography touch each other. It’s an art movement that has stayed with me, has haunted me for a long time. I have tried in my work to reproduce this imprecise thing where painting overlaps photography...

By the way, why didn’t we do this in English?

BB: We just naturally spoke in French, and dropped in a few English words from time to time. Maybe speaking in French and translating to English is a form of contre-emploi, a way to cover our own tracks?

(laughter)

DK: In lighting there is also a way to play against type. For example we use a very hard source, like the Arrimax, and we aim it at big bounces outside the window, but then inside I don’t put any fill at all, so that the lighting inside is very contrasty, but made from a very soft source. The direction of the light through the windows makes the image contrasty, the size of the windows makes it contrasty, but the light inside is very soft, like a Lowell Soft Light.

BB: Like the light in this living room.

[ Note: Darius is referring here to what is also called a zip light: a hidden bulb shines into a built-in curved reflector to create a soft bounced light.]

BB: Say more about accidental lighting.

DK: It’s a quest for realism, so that lighting feels accidental on the actors and the set. Even in with stylized photography, it’s good to go towards realism. Even on a sound stage, I want to make it extremely realistic. Not by having flat lighting, but by hiding the trail, to create an illusion of realism, because cinema is never the real, the real doesn’t exist, everything is a viewpoint, even documentary. Even surveillance cameras are placed in a certain position – and that’s a viewpoint.

+++

4. Directors

BB: You have worked with so many different top directors. What’s your advice to young cinematographers about working with a director?

DK: The first thing is to listen to the director. When you’re a director you are naked, it’s so hard. I’m a super passionate DP, I want to be near the director, like a brother, but no one worries about the movie like the director does.

But also you must make sure that it’s the right film before you decide to do it -- that means being sure that you can help the director. If the director has decided that they want to work with you, that’s great, but you need to be able to help him or her.

I have turned down movies because I couldn’t help the director. I’m only good for lighting a few movies, there are many directors that I wouldn’t be able to help. Or I would be the wrong person. Often you will see the wrong cinematographer working on a project.

BB: You can tell when you see the film...

DK: And by the stories you hear. You have to establish this magical connection with a director, and when it works, it’s incredible music, the film becomes very special. So my advice is to make sure you’re the right person for the project. And then listen.

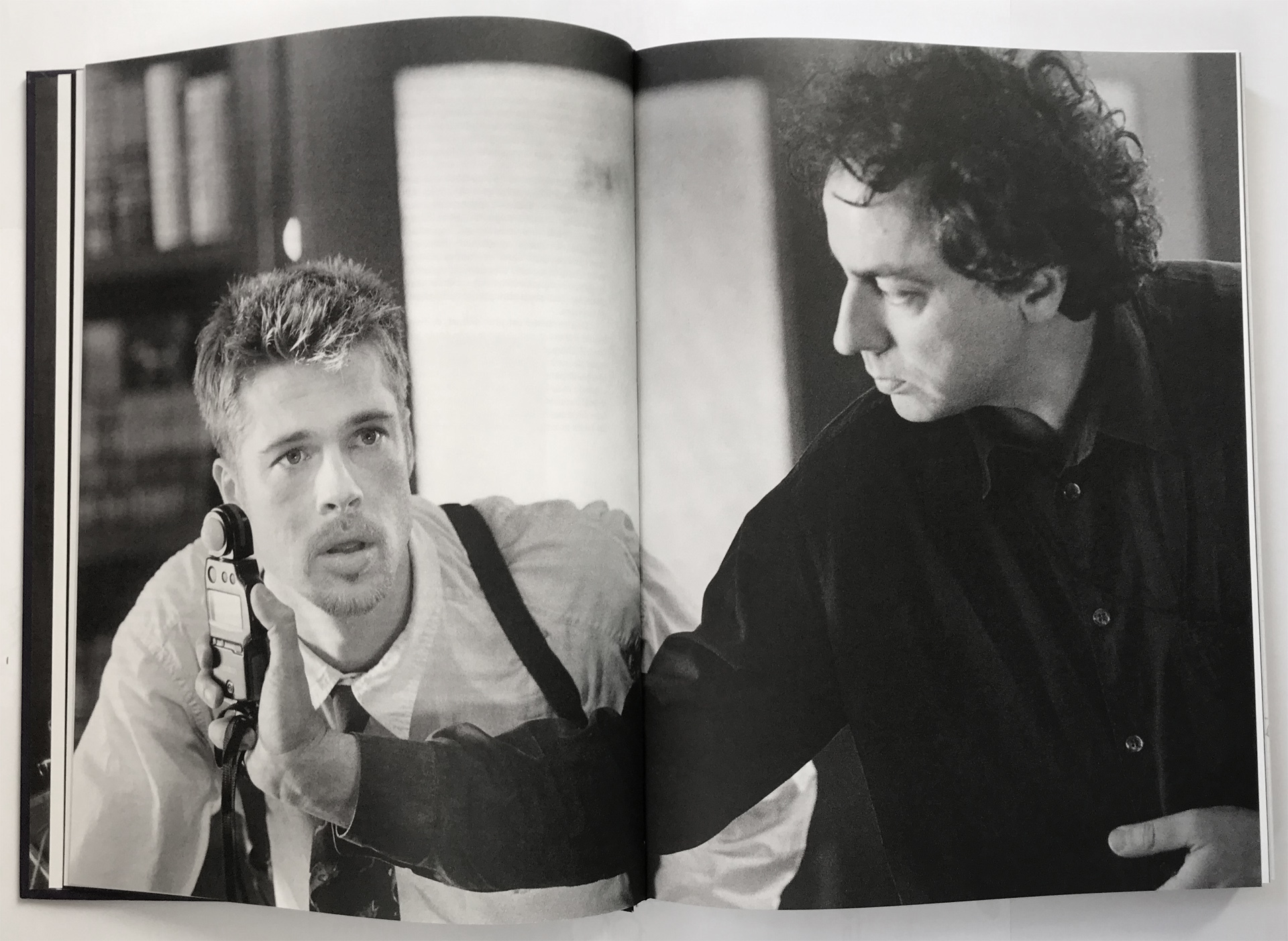

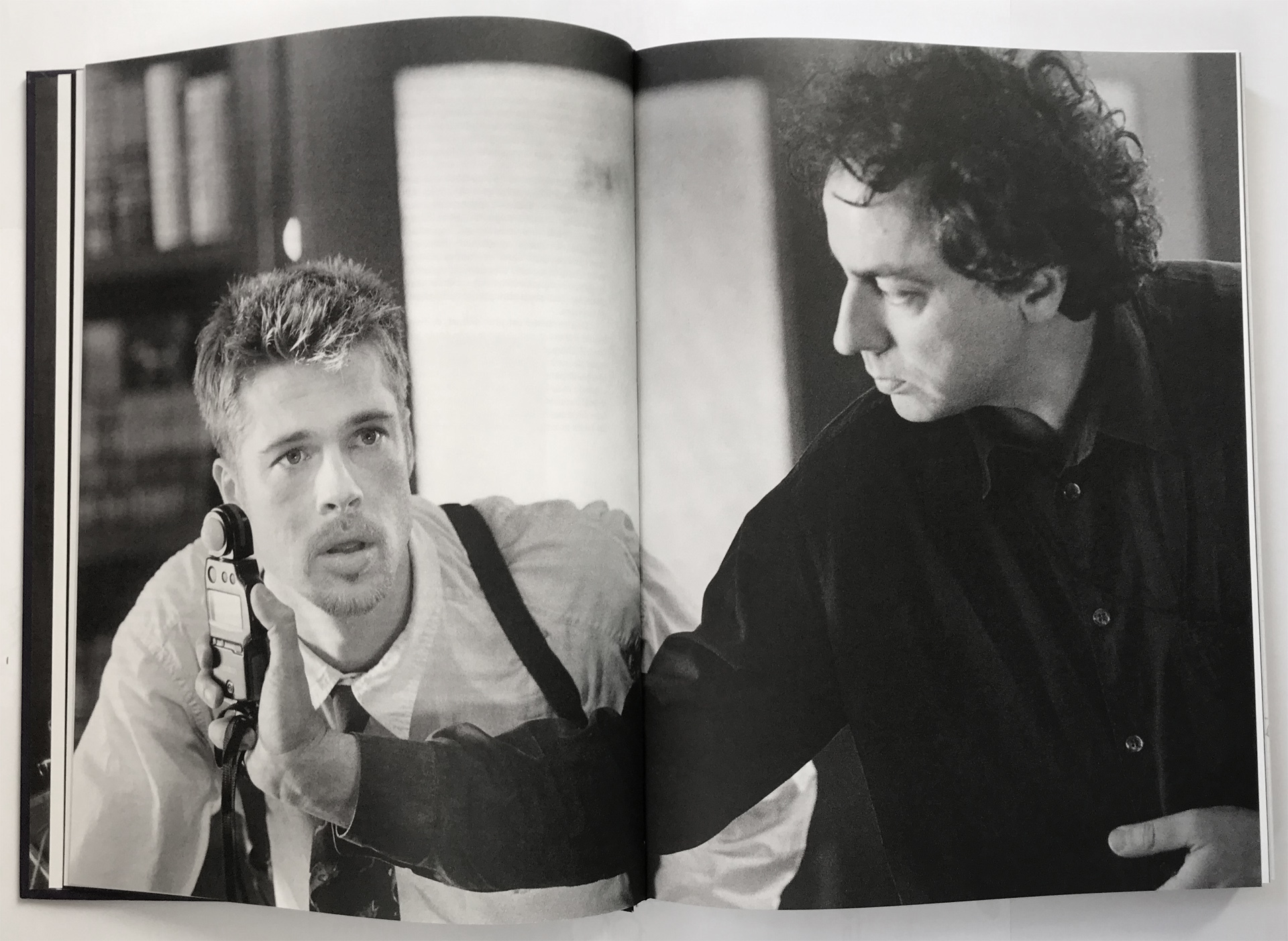

It’s important to say that some great directors are very present behind the camera. The image of a film belongs first to the director. For example, David Fincher was very present behind the camera, and with the lighting also. On Seven, we did a lot of tests ahead and we established our method for shooting the film. Once we set up the ambiance for the cinematography, we kept to it.

BB: How do you approach telling the story visually?

DK: You need a key to enter the world of the story. Sometimes it takes a while to find the key. It can come to you through a key word from the director, or an actor. Don’t try and figure out all the technical things. Just listen, try to have an image, have a taste inside you… a taste of the color, of the mood.

Once you have the key, you can push in that direction and you open this world. And then you get inside it and everything will fall into place naturally, like pieces of a puzzle. But if you don’t find the key, you’re lost. So you better find it!

BB: Where should you look for the key, if you haven’t found it?

DK: It could come from the way an actor interprets the story, but usually it comes from the director. In the middle of everything the director tells you about the film, there are key elements, something that tells you what the story is.

Then you tell yourself a story inside the story, but in accordance with the story the director is telling.

BB: You, the cinematographer, have your private story

DK: Yes, as an artist you have to create your own world, to create your own thing. But it has to be generated from what the director is doing.

So I’ve learned to listen to the director... I just listen.

+++

LINKS

thefilmbook: Visit with Darius Khondji, ASC, AFC - 1. Book, Dimming, Colors, Direction

thefilmbook: Visit with Darius Khondji, ASC, AFC - 2. Sources, Exposure, Contradictions, Directors

+++

synecdoche.fr: Conversations with Darius Khondji by Jordan Mintzer

YouTube: Master Class de Darius Khondji animée par Jordan Mintzer (in French)

+++

wikipedia.org: Darius Khondji

imdb.com: Yvan Lucas

wikipedia.org: Jean-Baptiste Mondino

wikipedia.org: Jean-Pierre Jeunet

YouTube: Carbon arc demo by Tim de la Torre

goodreads.com: A Man with a Camera by Nestor Almendros

wikipedia.org: Pictorialism

ascmag.com: Book Excerpt - Conversations with Darius Khondji by Jordan Mintzer

ascmag.com: Flashback - Seven by David E. Williams

ascmag.com: The Lost City of Z by Iain Marcks

+++

+++