9 Cinematographers Field Student Questions

ASC cinematographers behind projects as varied as Up in the Air, The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, Chicago Fire, Titanic and Medium Cool participated in an intimate Q&A with students from George Washington University and elsewhere at the ASC Clubhouse on June 17.

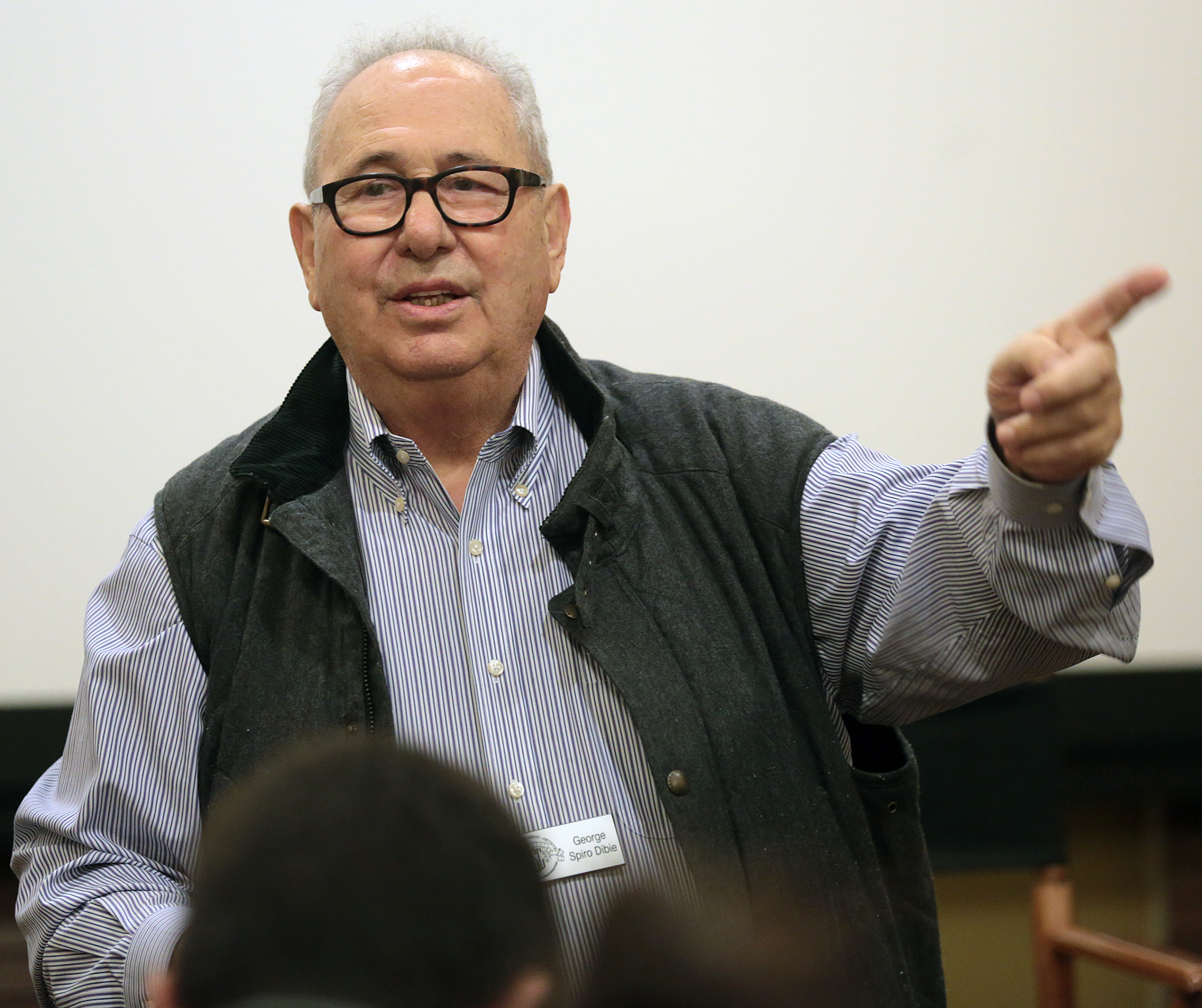

Moderated by George Spiro Dibie, chair of the ASC’s Education & Outreach committee, the conversation featured Russell Carpenter, Joan Churchill, Peter Moss, John Newby, Daniel Pearl, Eric Steelberg, Haskell Wexler (who shot the proceedings with his own camera) and Lisa Wiegand.

It was a wide-ranging discussion that lasted almost two hours, and the predominantly female audience kicked things off by asking why there aren’t more women cinematographers. In separate answers, the female panelists, Churchill and Wiegand, stated they are actually encouraged by the developments they’ve seen in recent years.

“I think there are more women learning to be cinematographers today than ever before,” said Churchill, an acclaimed documentarian whose credits include Last Days in Vietnam and Biggie and Tupac. “A few years ago, when I was the cinematographer-in-residence at UCLA, more than half my students were women.” She observed that documentary filmmaking is especially well suited to female artists. “When you make a documentary, your relationship with your subject is very important. You have to get the technical stuff down, of course, but you also have to be really interested in other people and understand how to engage them. I think that’s something women do very well.”

Wiegand, who recently wrapped her third and final season as the director of photography on NBC’s Chicago Fire, said, “I think this job is awesome, and I’ve wanted to do it since I was 15. I think that today, there are so many more opportunities for cinematographers, such a great variety of projects being made, that there’s a lot more room for more people to shoot, and an increase in women cinematographers will just become part of that.”

Dibie concurred, noting, “I think your only problem these days is competition.”

The question “When did you last shoot film?” received answers at opposite ends of the spectrum, with Pearl responding, “Two and a half weeks ago,” and Churchill answering, “2005.”

“All of my work is handheld,” said Churchill. “I can go days and days without putting the camera down. Having a small camera — one that lets my subject see my face — revolutionized the work I do. Plus, from my days of shooting film, I just remember that horrible feeling of going into the screening room with everyone else, waiting to see if we’d got it. I’m never going back!”

Moss, who recalled he hadn’t shot film in four years, observed that the format brought “a great professionalism” to the set that is largely lacking on digital shoots. Pearl agreed, noting, “The saying on a film set used to be ‘$1 a second.’ That created a kind of focus, a level of concentration, that has pretty much gone away. With digital, the attitude is, once you’ve got the camera, shooting is free.”

Carpenter, an Academy Award winner for Titanic, said he hadn’t shot film since 2011. “I enjoy shooting digital, but the pain of it is in post, where you can have 15 cooks in the kitchen,” he said. He added that the proliferation of digital-cinematography technologies has also led to an emphasis he finds “kind of distressing.”

“Camera manufacturers come at you with, ‘Shoot this in 8K,’ ‘Shoot at 120 frames per second,’ and so on,” Carpenter said. “Anymore, it feels like we’re making amusement parks where people can go for two hours, not films.”

In answer to the question “What movie do you wish you had shot?” the two youngest panelists, Steelberg and Wiegand, both cited black-and-white titles; Wiegand selected Citizen Kane, while Steelberg said he wished he’d shot “anything black-and-white, actually.” Satyricon, Blade Runner, Lawrence of Arabia and The Red Shoes were also mentioned by the panelists, as was “any film that Laura Poitras [Citizen Four] has shot.”

In answer to the question "Are you interested in shooting a movie based on a graphic novel?" Pearl said, “There’s no doubt that reading comic books when I was younger influenced my sense of composition, but I have no interest in shooting one of those movies.”

Carpenter agreed. “Some of the graphic-novel adaptations are brilliant stylistically, but story and character will always trump that for me,” he said. “I’d much rather shoot a low-budget film that’s all about the characters than something that’s 90 percent greenscreen or bluescreen.”

Newby recalled referencing a graphic novel when he shot the short-lived superhero TV series The Cape. “What’s interesting about graphic novels is they’re like storyboards, and filmmakers can find them very useful for that reason,” he said. “They can inform the work of the cinematographer, the production designer and the editor in particular.”

After emphasizing “the intimacy between form and content,” Wexler encouraged the students to “do something that you feel for or want to learn about. Being a filmmaker is a social obligation.”

Asked whether shooting television is more difficult than shooting a movie, the panelists agreed that the biggest challenge in television is the short schedule. “You have all these ideas, but you just don’t have the time to carry them out,” said Steelberg, who recently wrapped the Showtime pilot Billions.

Wiegand, who shot many independent films before moving into television, noted that one of the biggest differences between the two is the nature of the director-cinematographer collaboration. “On a movie the cinematographer and the director work very closely, starting with prep, but on a TV series the director is usually coming on as a guest, and the cinematographer is the one on set who’s most responsible for making sure the director stays within the show’s established style.”

Newby, whose credits include the series The Messengers and CSI: NY, said the evolution in viewing technologies has minimized some of the differences between the two. “With all the different screen sizes people are watching movies on now, and with TVs getting bigger and bigger, the notion of ‘big screen vs. small screen’ no longer applies,” he said. “In the past, when shooting television, you’d sometimes hear, ‘This isn’t going to be seen on a large screen, so you don’t need to do that kind of shot.’ You don’t hear that much anymore.”

When asked to cite favorite shots from their own work, Pearl pointed to a platform-dolly shot in the original Texas Chainsaw Massacre; Newby described a crane shot he operated for Ernest Dickerson, ASC, on Do the Right Thing; Carpenter named the shot that introduces Kate Winslet in Titanic; and Steelberg cited his own shot of Winslet, a scene in which a neighbor comes to her kitchen door in Labor Day. “[Director] Jason Reitman and I had planned it out, but the plan just wasn’t working, so we finally sent the actors away and just walked around the room with a viewfinder, working it out,” Steelberg recalled. “It ended up being my favorite shot in the movie.”

“Often the shots you’re having the worst time working out, whether for technical reasons or artistic ones, are the ones that turn out to be the best,” said Moss.

Wexler and Churchill responded to the question more broadly, with an emphasis on the truth at the heart of their documentary work. “There are moments when it’s just so magical, when somehow you’re able to capture the wonderment, excitement or terror someone is going through,” said Churchill.

“Yes,” said Wexler. “It’s that thrill I feel when I pan to someone and get a genuine reaction, a great reaction.” Turning to the students, he added, “I hope you find that.”